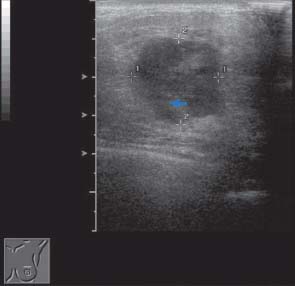

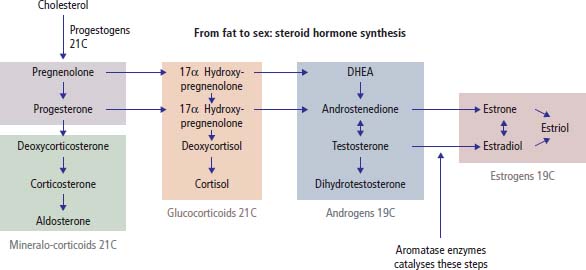

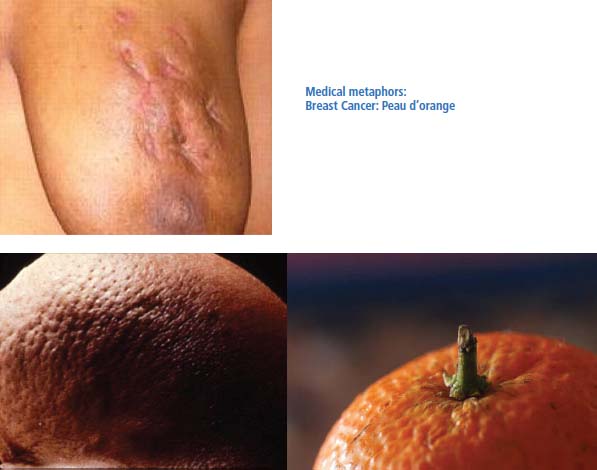

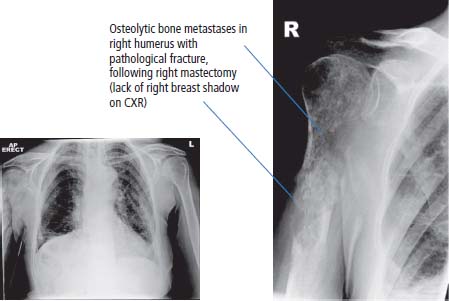

5 Diseases of the breast, including tumours, have been attracting medical interest for more than 5000 years. The earliest written records of breast cancer are in the Edwin Smith papyrus, from ancient Egyptian civilizations of 3000–2500 BC. Hard and cold lumps were recognized as tumours, whilst abscesses were hot. The next major advances in the management of breast cancer occurred during the golden age of surgery at the end of the 19th century, following advances in antisepsis and anaesthesia. William Halsted in Baltimore described radical mastectomy in 1894. Moreover, in an early example of surgical audit, he reported a local recurrence rate in 50 women of only 6%. The next major advance in the management of breast cancer occurred in 1896 with the development of surgical oophorectomy as a treatment strategy for advanced breast cancer, which was pioneered by George Beatson in Glasgow (the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research in that city is named after him). Geoffrey Keynes, the brother of macroeconomist John Maynard Keynes and an expert in the watercolours of William Blake, developed lumpectomy and radiotherapy as a breast conservation measure in the 1930s whilst appointed as surgeon at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. In the 1960s and 1970s the second-wave feminism movement in Europe and America took breast cancer as a campaigning point and their efforts led to increased focus on breast cancer treatment and research. Copying the AIDS awareness red ribbons, breast cancer activists adopted pink ribbons and now there is a rainbow of different cancer ribbons. These campaigns directly led to improvements in screening access, and screening programmes were introduced without a significant evidence base for efficacy and against the views of the medical establishment. As a consequence of increased screening, the survival rates of breast cancer have risen steadily over the last 30 years. A list of 5-year survival of breast cancer patients by stage of disease can be found in Table 5.2. Breast cancer patients were largely viewed as the property of the surgeons. In the United Kingdom in the last few years central governmental directives have led to multidisciplinary working. This has directly led to a decrease in the use of mutilating surgery and an increase in the use of adjuvant treatments. As a result of early detection and adjuvant therapies survival in breast cancer has increased significantly from around 65% in the 1980s to 85% in current times. Breast cancer is a common disease (Table 5.1 and Table 1.1). According to the most recent figures, 49,936 women are affected annually and 11,684 die in the United Kingdom as a result of this condition. The risk of breast cancer is influenced by family history, age, diet, social class and nulliparity. The risk of breast cancer rises with duration of exposure to oestrogens, so that early menarche, late menopause, low parity and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) all increase the risk. There is a protective effect of a full-term pregnancy, provided the pregnancy is achieved prior to the woman’s 30th birthday. There is a minor protective effect of having more than five pregnancies, but probably no protective effect from breastfeeding. Oestrogen-only HRT, as well as combined oestrogen and progestogen HRT, increases the risk of breast cancer in proportion to the duration of HRT administration. Both the oral contraceptive pill and alcohol and coffee consumption have been linked to breast cancer, but the associations are controversial. Breast cancer risk increases with age, plateauing during the menopausal years of 45–55. Women are at increased risk from breast cancer from non-vegetarian diets; it is not clear what the reason for this should be. Women who are more than two standard deviations above average height and weight are at a greater risk from breast cancer, as are women of social classes I and II. Table 5.1 UK registrations for (female) breast cancer 2010 A family history of breast cancer is a very important risk factor for breast cancer. If more than two first-degree relatives are affected, the risk to other female family members increases by a factor of 2. There are clear links between breast cancer and other cancers, with associations between ovarian and endometrial cancer and colonic tumours. There are four relatively common genes that lead to an increased risk of breast cancer and these are: BRCA1 and 2, CHEK2 and FGFR2. The prevalence and penetrance (percentage of people with the mutation that have the cancer) of mutations in these genes vary but lead to a lifetime risk of breast cancer of greater than 80% and up to 60% of ovarian cancer. BRCA1 gene is located on chromosome 17q21 and is a tumour suppressor gene, the product of which is involved in cell cycle regulation. The BRCA1 product binds with Rad51, a major protein of 3418 amino acids, which is involved in sensing and directing the molecular response to double-stranded DNA damage. Thus mutations of BRCA allow damage to DNA to go unrepaired and an accumulation of DNA mutations leads to cancers. BRCA2 gene is located on chromosome 13q12 and also has a role in DNA repair. To commemorate its discovery in 1994, a cycle path in Cambridge was painted with 10,257 stripes of colour, representing the nucleotide base sequence of the BRCA2 gene. The detected incidence of breast cancer is increasing in England and Wales. Similarly, death rates have fallen by nearly 30% over the last 15 years and survival chance has increased from 65% to 85%. These rises in incidence and survival are almost certainly due to the successes of the screening programme, which has led to the earlier detection of tumours at an earlier stage, with the resultant better prognosis. There are also contributions to this fall in mortality rate from an increased use of adjuvant chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. Women with breast cancer generally present to their clinicians with a lump in their breast. On average, there is a delay of approximately 3 months between the woman first noting the mass in her breast and her seeing a hospital clinician. As a result of concerns over the care of women with breast cancer, the investigation and treatment of this disease has been prioritized. Women in whom breast cancer is suspected must be seen in “outpatients” within 2 weeks of receipt of the referral letter. Table 5.2 Five-year survival of women with breast cancer by stage of disease Alternative sources of referral are from breast screening programmes. In the United Kingdom the breast cancer screening program was introduced as a political initiative during an election campaign. It was alleged that more money was spent on advertising the initiative than in the provision of screening facilities. The NHS Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) offers mammographic screening to all women aged 50–70 at 3 yearly intervals and currently over 2.7 million women are screened per year. A large proportion of screen-detected breast cancers are smaller than 2 cm without spread to the axillary lymph nodes or are in situ tumours only. Tumours are usually identified as a soft-tissue density or microcalcification within the breast. Large population-based randomized trials have suggested that mammographic screening reduces the mortality from breast cancer by 25% as a consequence of earlier diagnosis. However, breast screening is not without harm; radiation exposure, pain, psychological stress and perhaps most importantly overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis remains the most controversial issue in breast cancer screening and refers to the detection and subsequent treatment of breast cancers that would never have caused any harm to the patient in her natural lifetime (see Box 3.5). In 2013, a Cochrane review of screening trials involving 600,000 women concluded that for those trials where there was adequate randomization, there was no survival advantage to screening. Total 10-year breast cancer mortality was the same in screened and unscreened groups. Figure 5.1 Lateral view of a breast mammogram showing a large, dense, speculated mass highly suggestive of breast cancer. The current standard is for women to be seen in a multidisciplinary setting that offers a “one-stop shop” for diagnosis. Surgeons, with a special interest in breast cancer work in a clinic with oncologists, with access to same-day cytology and imaging services. A careful history should be obtained from the patient prior to examination when seen in outpatients. The mass may be thought to be benign or malignant. Benign lumps are more likely in younger women and tend to be painful and enlarge before menstruation. Malignant lumps tend to be more common in older women and are generally painless: only 30% of malignant breast lumps are painful and just 10% of lumps seen in new patients are malignant. Occasionally, women present with features of locally advanced (Figures 5.3 and 5.5) or metastatic disease (Figure 5.6). Diagnosis is carried out by clinical, mammographic (Figure 5.1), ultrasonographic, cytological and histological means. After clinical examination, mammography (a soft-tissue X-ray of the breast), aspiration cytology (removal of cells by means of a needle and syringe) and core biopsy (removal of a solid piece of breast tissue) should be performed to further assess the significance of the breast lump. In younger women, ultrasonography rather than mammography is the radiological investigation of choice. If there is confirmed malignancy, all women should then proceed to surgery within 2 weeks of diagnosis, as recommended by national guidelines. Figure 5.2 Breast ultrasound showing large, echo-dense, irregular, primary breast cancer lesion. Figure 5.3 Local recurrence of breast cancer showing multiple ulcerating skin nodules. There are two main pathological variants of breast cancer: ductal (70%) and lobular, and these may be in situ or invasive (or a mixture of both) (see Figure 1.9). Tumour grading was first described by Bloom and Richardson and bears their eponyms. This grading scheme depends upon the degree of tumour tubule formation, the mitotic activity and the nuclear pleomorphism of the tumour (see Box 1.3). As one might expect, poorly differentiated tumours have a worse prognosis than moderately differentiated ones, which in turn have a worse prognosis than well-differentiated breast cancer (Table 5.3). There may be pre-invasive changes and these are described as either ductal (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). LCIS are additionally graded according to their microscopic features (see Figure 1.9). Stage is defined according to the TNM classification, which is updated every 10 years or so (Table 5.4; see also Box 3.1). The subscript “P” denotes a pathological staging following surgery. The Nottingham prognostic index based upon the tumour size, N stage and tumour grade is used to predict 10-year survival in early breast cancer. Surgery for breast cancer depends upon the clinical stage of the disease. If the mass is less than 5 cm in size and not fixed, the preferred treatment is removal of the lump, which is termed “lumpectomy” or by the rather more elegant term “wide local excision”. Axillary lymph node dissection was conventionally performed, but now this has largely been replaced by sentinel lymph node biopsy which, if positive, may then be followed by an axillary clearance. The sentinel node is the hypothetical first node draining a cancer. The reason for sampling the axillary nodes is that if the nodes are affected, there is a significant advantage in this group of women to adjuvant chemotherapy. In the “node-negative” woman there is a very much smaller advantage to adjuvant chemotherapy. In an older woman there may be an argument against routine axillary dissection. The reason for this is that adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy within this group of women is not dictated by lymph node status, because the advantage is much smaller than in younger women and the toxicity of the treatment outweighs these modest gains. It is clear, however, that knowledge of the axillary nodal status does provide prognostic information. Table 5.3 Breast cancer grading and prognosis For a woman whose tumour measures >5 cm in size, the preferred surgical option is mastectomy, which is removal of the breast with axillary dissection. This is to reduce the chance of local recurrence. For more advanced breast cancer, the value of surgical treatment is much more contentious and elderly women may be treated with hormonal therapy alone if the breast cancer expresses oestrogen receptors and/or progesterone receptors (see Figure 1.14). In a younger woman, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be given in the first instance, to reduce the size of the tumour and this may then be followed by surgery and radiotherapy. There is a major role for reconstructive surgery and this may be carried out at the time of primary surgery or at a later date upon completion of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy. The psychological gain is tremendous and needs to be considered in older as well as younger women, for breasts are considered valued personal property in older just as much as in younger women. After lumpectomy, radiotherapy is given to the breast. This is done in order to reduce the risk of local recurrence of the tumour. Without radiation this risk is between 40% and 60%; whereas with radiation, the risk is reduced to approximately 4–6%, which is the same as that for more radical surgical procedures. Radiotherapy is generally given over a 6-week period and requires daily attendance at hospital. The side effects of radiation include tiredness and burning of the skin, which is generally mild. More serious consequences of radiation are seen only rarely and include damage to the brachial nerve plexus and, with more old-fashioned treatment machines and plans, damage to the coronary blood vessels. Rarely, a second cancer, such as an angiosarcoma, may follow at the site of radiotherapy treatment. Treatment with tamoxifen has been shown to have an advantage in terms of disease-free and overall survival in both pre- and postmenopausal women and is now given routinely to this group of patients. It is usually recommended that treatment should extend for 5 years. There is no advantage to adjuvant tamoxifen in oestrogen receptor-negative tumours. There have been changes in our understanding of the oestrogen receptor. Two different classes of oestrogen receptor (ER), described as α and β, have been identified. Tamoxifen is a selective ERα-antagonist, which, in turn, has effects on the progesterone receptor. In postmenopausal women, recent studies suggest that a newer group of drugs, the aromatase inhibitors, may be even more effective than tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy. The current standard is to give sequential therapy with tamoxifen and then an aromatase inhibitor. Treatment is given for a total of 5 years. Approximately 10% of circulating oestrogens derive from adrenal precursors, such as androstenedione, through the action of aromatase enzymes. The aromatase inhibitors block this action, limiting the synthesis of oestrone and oestrone sulphate produced by a second series of enzymes – the sulphatase system (Figure 5.4). Use of aromatase inhibitors is associated with osteoporosis. There have been reports of cases of endometrial carcinoma associated with the use of tamoxifen. The estimated risk is one case per 20,000 women per year of use. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMS) targeting tumour, and not normal tissues, may avoid the risk of uterine malignancy. However, there may be advantages to non-selective oestrogen inhibitors in terms of the prevention of osteoporosis. Table 5.4 TNM staging of breast cancer Figure 5.4 Sex hormone synthesis pathway (21C, 21 carbon compound 19C, 19 carbon compound). DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone. Figure 5.5 Peau d’orange is caused by lymphoedema of the skin with tethering of the sweat ducts giving a dimpled appearance to the swollen skin resembling the skin of an orange. Adjuvant chemotherapy has a significant place in the management of breast cancer. Adjuvant chemotherapy using the cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil (5FU) (CMF) programme was the first shown to be of benefit. A large international study showed that more intensive therapy using the FEC (5FU, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide) regimen is more effective than CMF. The addition of taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel) chemotherapy given in the adjuvant setting confers further benefits. Third generation adjuvant chemotherapy (FEC-T), combining FEC and docetaxel, is now considered to be the standard. There is no evidence that intensifying adjuvant therapy any further using, for example, high-dose treatments with bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell support, improves the disease-free interval or the overall survival. About a quarter of breast cancers express the epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (EGFR2), also known as Her-2/neu and c-erbB-2 (see Figure 1.14). This is the target for the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab (Herceptin). For patients with Her-2 receptor-positive tumours, treatment with adjuvant trastuzumab may be considered. Treatment is conventionally given for periods of 12–18 months. The advantage to treatment with trastuzumab is small, but is recommended because of the poorer survival of women with tumours that strongly express Her-2. The toxicity of treatment with trastuzumab is significant, and particularly of note are the direct cardiac effects that may manifest as heart failure. The treatment of metastatic breast cancer depends very much upon the age of the patient and the sites of metastasis. It is only rarely curable and so life quality issues are immediately important. When we described this point to one patient, she replied: “my dear, it’s the quality of death that bothers me”. In older women whose metastases are in the skin or bone, the preferred treatment option is hormonal therapy (see Figure 3.26), provided that the tumour expresses oestrogen and/or progestogen receptor positivity. The agent of first choice is tamoxifen because of its lack of toxicity and efficacy. Approximately 70% of women aged 70 respond to this therapy. In a younger woman the growth of breast cancer is frequently dependent upon oestrogens derived chiefly from the ovaries. In a premenopausal woman, hormonal therapy is generally less effective than in postmenopausal women, and at the age of 30, just 10% of patients overall will respond to treatment at all. But regardless of this statistic oophorectomy, that is, removal of the ovaries by either radiotherapeutic, surgical or medical means, is generally the first therapeutic stratagem. Surgical oophorectomy is unnecessary, given that an equivalence of effect is provided by the use of medical treatment with a luteinizing hormone receptor hormone (LHRH) agonist. How much easier is it to provide a simple 3-monthly depot injection than to expose a woman to laparoscopy and surgical oophorectomy. Radiotherapy is not a particularly successful way of causing gonadal failure. Ovaries are relatively radiotherapy resistant and the conventional dosages of radiotherapy given to sterilize may not sterilize a younger woman and certainly will not lead to an instant reduction in circulating ovarian steroid hormones. So for a premenopausal woman, treatment with an LHRH agonist is generally recommended as the first therapeutic hormonal manoeuvre. Other sources of hormones are from the adrenal glands, diet and peripheral tissues. As a result of our knowledge of the steroid biosynthetic pathways, inhibitors of these pathways have been developed. In recent years we have seen the introduction of aromatase inhibitors into clinical practice. These drugs inhibit the enzymes that convert androgens manufactured in the adrenals into oestrogens (Figure 5.6). Further hormonal therapies are also likely to become available because of Pharma interest in the development of oestrogen sulfatase inhibitors. The sulfatases are enzymes involved in the final steps of oestrogenic steroid synthesis and sulfatase inhibitors are in clinical development currently. Triple negative breast cancers lack expression of ER, PR and HER2; they constitute about 15% of all breast cancers and have an aggressive natural history. These triple negative tumours resemble BRCA1-associated breast cancers and are highly sensitive to chemotherapy with DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin, and the effects of these drugs can be potentiated by the use of poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors which disable DNA base excision repair. PARP inhibitors (postfix: -parib) are also effective in BRCA1-associated breast and ovary cancers. Angiogenesis inhibitors, such as the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, have also been shown to have a modest beneficial effect in breast cancer. The erythroblastic leukaemia oncogene (ErbB) family of receptor tyrosine kinases includes four members: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), HER 2, HER3 and HER4. A significant proportion of breast cancers express HER2 which may be targeted with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab or the oral kinase inhibitor lapatinib that inhibits both HER2 and EGFR. Breast cancer therapy is rapidly evolving into a form of personalized medicine where treatment is based on decisions made from tumour array comparative genome hybridization (CGH) and next generation sequencing techniques (see Figure 1.13). Figure 5.6 Metastatic breast cancer. In both pre- and postmenopausal women, radiation treatment is very effective in controlling bone pain. The addition of regular bisphosphonate therapy both relieve bone pain and reduce skeletal events such as fractures and spinal cord compression. If lungs or liver are affected, then chemotherapy is required. Overall, between 40% and 60% of patients respond to chemotherapy and this response is for a median duration of 1 year. The median survival of women with metastatic breast cancer ranges between 18 and 24 months, with 5–10% alive after 5 years. It should be noted that there are patients with very prolonged survival, and these include those women who have, for example, single sites of metastatic disease. Breast cancer responds to chemotherapy, but often after responding, patients relapse and die. There have been attempts to maximize response rates by intensifying chemotherapy. High-dose treatments were popular in the early 1980s. Response rates were found to be higher than for conventional treatment; toxicity, however, was significantly worse, and death rates reached 20% as a result of the side effects of treatment. Even more significantly, patients who responded and survived the toxicity later relapsed, and the median duration of response was no better than that expected with conventional treatment. In the 1990s, there was an increase in the numbers of patients receiving high-dose therapy for breast cancer. This was possible as a result of the improvement in supportive therapy, principally bone marrow rescue, either with stem cells or with marrow. Mortality has decreased and now is 5% in the best centres. Overall, there has been no significant improvement in the expectation for survival for patients with metastatic breast cancer, and only 20% of patients are alive 2 years after the transplantation. It has been recently argued that the relatively good results of intensive therapy reported in early studies are entirely the result of the selection of good-prognosis patients for treatment with high-dose therapy, and that the same effects could be achieved with less intensive, conventional therapy. It may be the case that early intensive therapy given as adjuvant treatment to patients with poor-risk tumours will lead to improved survival, but this has not been shown in any randomized study. The introduction of universal mammography has led to an enormous increase in the diagnosis of relatively benign breast conditions such as DCIS and LCIS. The latest ONS statistics describe 5765 men and women diagnosed with carcinoma in situ in 2011. DCIS, diagnosed by excision biopsy and untreated will progress to invasive cancer in 40% of patients over 5 years. Treatment with adjuvant radiotherapy will limit this progression rate to 1–4% per annum. Mastectomy is an alternative to radiation therapy. Both radiotherapy and mastectomy are equally effective in local disease control. In randomized control studies tamoxifen has been shown to prevent local recurrence in women who have DCIS. LCIS is associated with a high incidence of bilaterality reaching up to 40% and mirror biopsy is recommended of the contralateral breast. Adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy is not helpful in preventing LCIS recurrence. The mortality rate from carcinoma in situ is less than 1%. This is an eczematous condition of the nipple, associated in 80% of cases with an underlying ductal carcinoma and in about 20% of cases with underlying DCIS. It was named after Sir James Paget, who also bagged Paget’s disease (of bone) and extramammary Paget’s disease as eponyms. He was a friend of Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley as well as father to Stephen Paget who first proposed the “seed and soil” hypothesis of tumour metastasis. Breast cancer in men is rare accounting for <1% breast cancer (349 cases in the United Kingdom in 2011). At presentation, men with breast cancer are on average 10 years older than women with breast cancer and >40% are stage III or IV. Initial treatment combines mastectomy and tamoxifen as most tumours express ER. Mastectomy is required in order to obtain “good” tumour margins which minimizes the risk of local recurrence. The overall survival is worse than in women and relates to the advanced stage at diagnosis with overall 5-year survivals of 40–60%. Case Study: A TV producer with a breast lump.

Breast cancer

Epidemiology

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registration

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5 year overall survival

Female

Female

Female

Female

Female

Breast cancer

31

1st

1 in 8

+6%

85%

Presentation and screening

Tumour stage

Percentage of patients at diagnosis

Stage definition

5-year survival

Stage I

41

Tumour <2 cm, no nodes

88%

Stage II

45

Tumour 2–5 cm and/or moveable axillary nodes

69%

Stage III

9

Chest wall or skin fixation and/or fixed axillary nodes

43%

Stage IV

5

Metastases

12%

Diagnosis

Staging and grading

Treatment

Surgery

Grade

5-year survival

G1: Well differentiated

95%

G2: Moderately differentiated

75%

G3: Poorly differentiated

50%

Adjuvant radiotherapy

Adjuvant hormonal therapy

T stage (primary tumour)

N stage (nodal status)

M stage (metastatic status)

T0: No detectable primary tumour

N0: No nodes involved

M0: No metastases

T1: Tumour less than 2 cm

N1: Mobile axillary nodes

M1: Spread to distant organs

T2: Tumour measuring between 2 and 5 cm

N2: Fixed axillary nodes

T3: Tumour measuring greater than 5 cm

N3: Involved supra- or infraclavicular nodes

T4: Tumour of any size extending into skin or chest wall

Adjuvant chemotherapy and receptor targeting therapy

Treatment of metastatic breast cancer

High-dose chemotherapy

Carcinoma in situ

Paget’s disease of the nipple

Male breast cancer

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree