27 Brainstem Tumors

Epidemiology and Classification

Epidemiology and Classification

Brainstem tumors (BSTs) are predominantly found in the pediatric population, with a mean age at presentation of between 7 and 9 years.1–3 Overall, BSTs represent 10 to 15% of pediatric brain tumors.4–6 The incidence in the United States is estimated to be between 5 and 10 cases per 10 million people per year,1,7–15 and BSTs do not appear to have a predilection based on sex, race, or geographic location.

Historically, BSTs were considered as a uniform group of inoperable tumors. It was not until the advent of neuroimaging in recent decades that classifications began to emerge to describe the heterogeneity of this group of neoplasms.9,10,16 Although minor variations exist between the various classification systems, they all aim to classify BSTs according to biological behavior and location and are the basis for selecting patients for surgery. For example, BSTs have been classified as diffuse or focal, and the focal tumors were further subdivided into midbrain, pontine, dorsally exophytic, and medullary.17 A simplified classification into diffuse, focal, and exophytic has also been proposed.18 This system has been found to be very valuable in selecting patients for surgery and discussing prognosis with families (see text box).

Several large series have now reported the distribution and prognosis of BSTs among the various subgroups. It has been estimated that between 58% and 75%9,10,16 of BSTs are diffuse, and approximately 25% are focal. Diffuse tumors originate from the pons and are now often referred to as diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPGs). These lesions have a dismal prognosis and were previously thought not to be amenable to surgical therapy. Focal tumors can be found in any part of the brainstem and may be completely surrounded by brainstem tissue or may reach the surface. Focal tumors that grow out of the brainstem are referred to as exophytic. The exophytic portion may be dorsally, laterally, or ventrally located. In general, the focal and exophytic tumors are lower grade, present with a longer history, are sometimes surgically resectable, and have a much better prognosis than the diffuse tumors.

Classification of Brainstem Tumors

• Diffuse

• Focal

Midbrain

Midbrain

§ Tectal

Pons

Pons

Medulla

Medulla

§ Cervicomedullary

• Exophytic

Lateral/ventral

Lateral/ventral

Dorsally exophytic

Dorsally exophytic

Pearl

• Diffuse tumors originate from the pons and are often referred to as diffuse pontine gliomas. These lesions have a dismal prognosis and are not amenable to surgical treatment.

The dorsally exophytic tumors, a special subtype of the focal tumors, were first described about 25 years ago.12 They are unique in several respects. They are almost completely extramedullary, filling the fourth ventricle and mimicking other fourth ventricle tumors. The exophytic component often enhances. They are usually pilocytic,15 and, as a result of these favorable features, they are considered by many to be a surgically curable subtype with favorable long-term outcomes.

A second type of focal BST is the tectal glioma. This lesion usually presents with hydrocephalus secondary to obstruction of the aqueduct. Typically, these tumors do not enhance and have a very indolent course such that management of the hydrocephalus is the main issue.

Once exophytic and focal BSTs were described, surgical approaches to these lesions were introduced. As experience in the surgical treatment of BSTs increased, a variety of pathological diagnoses were encountered, including pilocytic and fibrillary astrocytomas, gangliogliomas (low-grade and anaplastic), gangliocytomas, primitive neuroectodermal tumors (medulloepitheliomas), and ependymomas.19 Nevertheless, gliomas, especially low-grade gliomas, are the most common histology for the focal and exophytic tumor groups, and surgery should be considered for these lesions.

Pearl

• In general, the focal and exophytic tumors are lower grade, present with a longer history, are sometimes surgically resectable, and have a much better prognosis than the diffuse tumors.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of BSTs provides essential information for their diagnosis and management. The congruence of clinical presentation and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) strongly predicts the BST type and is the basis for management decisions. Children with diffuse BSTs typically present with a triad of cerebellar dysfunction (87%), cranial neuropathies (77%), and long-tract signs (53%). Cerebellar dysfunction is often in the form of gait instability, whereas paresis is a common manifestation of long-tract compromise. The cranial nerves most frequently affected are V, VI, and VII. Hydrocephalus is a relatively uncommon finding at presentation (< 20%). Leptomeningeal dissemination has been reported in 4 to 39% of cases during relapse.20 Although not all children present with the triad, the multiplicity of symptoms is strongly predictive of a poor outcome. In one report the presence of symptoms from at least two of the three categories in the triad predicted death within 18 months, with a 97% positive predictive value in 33 children.21

Rapid evolution of symptoms is another hallmark of diffuse BSTs. Among children with diffuse BSTs, the interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis was less than 1 month in 55% of patients, less than 3 months in 80%, and within 6 months in 94%.13 Similar to symptom multiplicity, the duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis also correlates with survival. A median survival of 12.9 months was reported with an interval of 1 to 4 weeks, compared with 19.5 months with a longer duration prior to diagnosis.22 Other studies have also reported similar findings, with decreased survival for patients with symptoms of less than 1 month’s duration compared with those with symptoms lasting 6 months or longer.7,8,17,21

In contrast to the diffuse BSTs, the presentation of focal BSTs is much more indolent and is usually measured in months to years. In our series of 28 children with focal pilocytic tumors of the brainstem, the most common presentation (86%) was a focal neurologic deficit of cranial nerves with or without motor or sensory long-tract findings. Of those patients, 25% also presented with hydrocephalus and one of them suffered from seizures. Two patients presented with hydrocephalus only, and two others presented with headaches alone. As expected, the nature of the cranial nerve deficits and the presence of hydro-cephalus corresponded to the anatomical location of the tumor. Midbrain tumors, most commonly tectal gliomas, usually present with signs and symptoms of progressive hydrocephalus. Parinaud syndrome, oculomotor palsies, and long-tract findings are less common except for tumors that involve the tegmentum. Patients with intrinsic focal pontine tumors may present with diplopia, facial weakness or numbness, hearing loss, and paresis, whereas the dorsally exophytic variant, which typically arises from the medulla, presents more often with hydrocephalus from fourth ventricular obstruction. Additionally, patients with medullary tumors can present with dysphagia, hoarseness, nausea and vomiting, ataxia, and paresis, often in the context of recurrent upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia as a result of silent aspiration. The prolonged history, often with gastrointestinal or respiratory investigations, is a hallmark of the medullary tumors.

Special Considerations

• Children with diffuse BSTs typically present with a triad of cerebellar dysfunction (87%), lower cranial neuropathies (77%), and long tract signs (53%).

• Rapid evolution of symptoms is a hallmark of diffuse BSTs. In contrast to the diffuse BSTs, the presentation of focal BSTs is much more indolent and is usually measured in months to years.

Molecular Genetics

Molecular Genetics

Studies have shown that diffuse BSTs share similar genetic alterations with pediatric high-grade gliomas but have molecular characteristics that distinguish them from adult gliomas. The role of epidermal growth factor and downstream signaling pathways in high-grade gliomas has been well established.23 In diffuse BSTs, both p53 mutation (a tumor suppressor gene mutation associated with secondary glioblastomas) and epidermal growth factor receptor amplification (associated with primary glioblastomas) have been identified.24 This may explain their similarities with glioblastomas in terms of their aggressive biological behavior. Studies have also shown molecular alterations leading to overexpression of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) in diffuse pediatric pontine gliomas.25,26 This may serve as a useful target for treatment of these therapeutically challenging tumors. Furthermore, the association with secondary glioblastomas raises the possibility of malignant transformation in these diffuse BSTs, which could explain the long-standing problem of the poor predictive value of biopsies of these tumors.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Brainstem Tumors

Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) who have brainstem tumors appear to have a more favorable prognosis than those without NF1. With a median follow-up of 3.75 years, none of the nine NF1 patients with diffuse BSTs progressed and required intervention in one report.27 In another study (in which 14 of 17 patients had primary focal medullary lesions), a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 82% was reported with a median follow-up of 52 months.28 This is in contrast to the 51% 5-year PFS in our series of non-NF1 patients with predominantly focal medullary tumors.14

In NF1 patients, it is particularly important not to confuse the diagnosis of BSTs with the commonly identified T2 signal abnormalities in the brainstem, which exhibit few, if any, symptoms and little growth.29–31 Another clue to the diagnosis of NF1 is T2 signal abnormality in the globus pallidus. Because of the more indolent nature of these NF1 BSTs, the current recommendation is a conservative one with observation, and intervention should be reserved only for lesions that exhibit clinical or imaging changes.

Imaging Studies

Imaging Studies

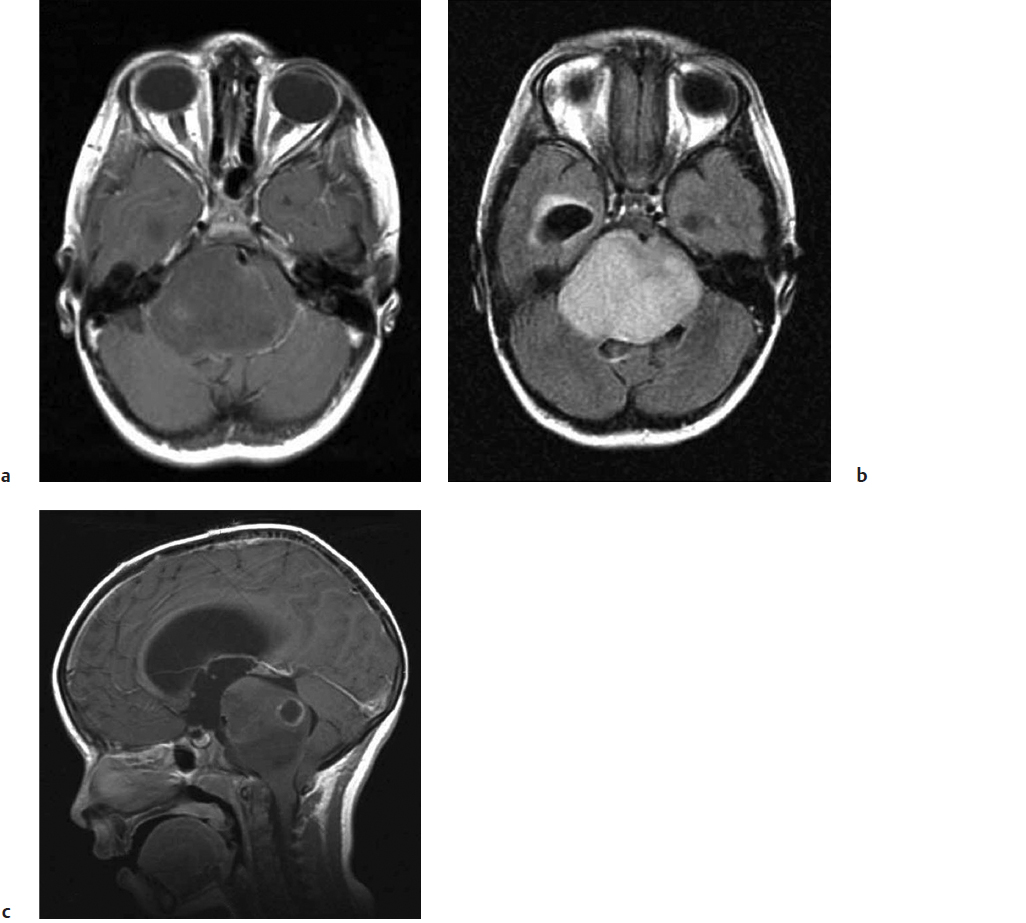

Although computed tomography (CT) may aid the diagnosis in a few selected cases (the presence of calcium may suggest oligodendroglioma or an occult vascular malformation32), smaller focal tumors are often missed on routine CT imaging. At present, MRI is the imaging modality of choice in the evaluation of BSTs. The neuroimaging features of diffuse BSTs can be misleading and often do not correlate with clinical features.33 For example, MRI is not specific for distinguishing lower from higher grade neoplasms unless focal enhancement or diffusion restriction (implying a higher-grade lesion) is present. The most striking feature is an enlarged (“fat”) pons (Fig. 27.1a). On T1-weighted images (T1WIs), the lesion appears hypointense with ill-defined margins blurring into the adjacent parenchyma. On T2-weighted images (T2WIs), the lesion is hyperintense, and the extent of tumor infiltration is much better appreciated because signal intensities extend cranially into the midbrain or caudally into the medulla usually beyond the margin of the T1 abnormality (Fig. 27.1b). With gadolinium, about a third of diffuse BSTs enhance, usually heterogeneously (Fig. 27.1c). The role of biopsy in these tumors remains controversial. Biopsy is considered when the presentation (clinical or imaging) is atypical (Fig. 27.2). Recent advances in the molecular genetics of diffuse BSTs may lead to a paradigm shift favoring biopsy to better understand tumor biology and to identify new therapeutic targets.33

In contrast, focal BSTs are usually smaller and are well demarcated on MRI (Fig. 27.3). They have homogeneous enhancement, especially when they are pilocytic in origin, and they may have a cystic component. Unlike their diffuse counterparts, these lesions are typically noninfiltrative with their T1WIs and T2WIs superimposable (Fig. 27.4). Focal BSTs may present on the surface of the brainstem and may have an exophytic component.

Fig. 27.1a–c Diffuse pontine glioma demonstrating a diffusely enlarged “fat” pons that (a

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree