Bowel Obstruction

Douglas J. Schwartzentruber

Matthew Lublin

Richard B. Hostetter

Background

Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with cancer are quite common. These include xerostomia, dysphagia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. These symptoms can be generally improved or ameliorated with a variety of medical interventions (reviewed in (1). Opioids, chemotherapeutic agents, and tumor can lead to abdominal pain, ileus, constipation, and vomiting that mimic mechanical bowel obstruction. Bowel obstruction may be a primary presentation or a secondary complication of a malignancy. Obstruction can involve either the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract, and the site of obstruction determines the management. Initial management is generally conservative and consists of hydration and nasogastric decompression. The decision to proceed with surgical intervention needs to be individualized to each patient. Palliative management of bowel obstruction is often required in the patient with cancer. Determining the course of palliative therapy can be challenging and one must balance the individual patient’s needs and desires with clinically sound judgment. Patients with cancer can be palliated either medically or surgically. Operative treatment of gastrointestinal obstruction accounted for one third of 1022 palliative surgical procedures in a series of 823 patients (2). End-stage patients and patients who are not candidates for surgery should receive effective medical palliation.

Incidence

Upper gastrointestinal obstruction in the US population is more commonly caused by malignancy than ulcer because of the introduction of proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers (3). Gastric carcinoma is the most common malignancy causing gastroduodenal obstruction, followed by pancreatic carcinoma (3). Most patients with gastric cancer do not present with obstruction. Patients with pancreatic cancer initially present with upper gastrointestinal obstruction in 6% of the instances (4, but after diagnosis, the incidence of gastroduodenal obstruction increases (5, 6). In a review of 350 patients with pancreatic cancer, 25% of patients with unresectable disease developed gastroduodenal obstruction (4).

In contrast to gastroduodenal obstruction, small bowel obstruction in the general population is less commonly the result of malignancy. In a review of 238 patients with a diagnosis of small bowel obstruction, malignancy was the third most common cause of obstruction (7%) after adhesions and hernias, accounting for 88% (7). The incidence of small bowel obstruction is much higher in the cancer population and is generally secondary to metastatic cancers arising from other sites. In a review of 518 patients with ovarian cancer, 127 patients (25%) developed intestinal obstruction (8) that directly correlated with the stage of the disease. In colorectal cancer, 41 of 472 (9%) patients developed small bowel obstruction after primary resection of their cancer (9).

Unlike small bowel obstruction, acute colonic obstruction in the general population is caused by primary malignancy of the colon in most patients. Approximately 15–20% of patients with colon carcinoma present with obstruction (10). In patients presenting with colonic obstruction, 53–78% are due to a primary colorectal carcinoma, whereas only 6–12% are due to extrinsic compression of the colon from metastases (11, 12).

Etiology

In most patients with cancer, symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation are nonobstructive in origin. Certain chemotherapeutic agents cause ileus, resulting in nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Vincristine is quite notorious for this, and in one series, 46% of patients reported constipation or abdominal pain or both (13). Nonchemotherapeutic agents such as opioids and anticholinergics may also lead to adynamic ileus. Further, patients with malignancy are often bedridden, inactive, malnourished, dehydrated, and have electrolyte imbalances. The common event of postoperative ileus can also be quite protracted in the patient with cancer. These states can lead to bowel dysmotility and the resultant clinical presentation may mimic mechanical bowel obstruction.

When present, mechanical bowel obstruction may involve the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract. The most frequent site of obstruction is the small bowel (14). Gastroduodenal obstruction is rarely benign in nature in the patient with cancer. The obstruction may be secondary to a primary stomach cancer or due to direct extension from the kidney, pancreas, biliary, or colon carcinoma. Ovarian carcinoma can also lead to gastroduodenal obstruction.

In contrast to gastroduodenal obstruction, a significant percentage of small bowel obstructions occurring in the patient with cancer are benign. In the reviewed series, 28% (median) of small bowel obstructions were the result of benign processes such as adhesions from previous oncologic operations (Table 16.1). However, most of the small bowel obstructions (72%) were caused by a recurrence of the intra-abdominal malignancy. Few patients present with primary small bowel tumors as the cause of obstruction (15). A primary

small bowel tumor (adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, carcinoid, and lymphoma) should be suspected in patients with abdominal pain, weight loss, and occult gastrointestinal bleeding (16). Metastatic small bowel lesions should be considered in patients with the symptoms mentioned in the preceding text and a prior history of cancer of the ovary, colon, stomach, pancreas, breast, or melanoma.

small bowel tumor (adenocarcinoma, sarcoma, carcinoid, and lymphoma) should be suspected in patients with abdominal pain, weight loss, and occult gastrointestinal bleeding (16). Metastatic small bowel lesions should be considered in patients with the symptoms mentioned in the preceding text and a prior history of cancer of the ovary, colon, stomach, pancreas, breast, or melanoma.

Table 16.1 Intestinal Obstruction om Patients With a Previous Diagnosis of Malignancy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Colorectal, ovarian (gynecologic), and gastric are the most common (nearly 75%) primary tumors in patients with subsequent small bowel obstruction (14, 17, 18, 20). Less frequent are melanoma, mesothelioma, and a variety of other intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal sites of tumors such as pancreas, breast, or lung. Melanoma is the most common cause of malignant intussusception in the adult population (22). Therefore, small bowel lesions may cause obstruction by their intraluminal occlusion, extraluminal compression, or by intussusception (16).

Colorectal cancer can lead to obstruction of the colon and small bowel obstruction. Primary large bowel obstruction is most commonly caused by colon carcinoma (78% of patients) (12). Noncolonic malignancy (12%) and benign causes (10%) account for the rest. Owing to the increased diameter of the right-sided colon and the fecal consistency, left-sided colon cancer obstructs more readily than right-sided malignancies. Intussusception is an infrequent mechanism of obstruction in these patients (12). Ovarian and prostatic carcinoma may obstruct the colon by peritoneal carcinomatosis or direct extension. Extra-abdominal cancers such as breast cancer metastases may also lead to large bowel obstruction.

Late radiation injury to the bowel may be the source of bowel obstruction (23). The small bowel is the predominant site of obstruction after radiation in approximately 90% of instances.

As mentioned previously, not all bowel obstructions in patients with cancer are mechanical in nature. A patient presenting clinically with obstructive symptoms may have intestinal dysmotility or pseudo-obstruction. The pathophysiology of pseudo-obstruction in the patient with cancer has been attributed to the denervation of the bowel and mesentery by carcinoma, metastatic infiltration of the celiac plexus, and paraneoplastic syndromes (24). Ogilvie’s syndrome, as classically described, refers to pseudo-obstruction as a result of extra-abdominal metastatic carcinoma invading the celiac plexus, leading to sympathetic denervation (25). These patients were noted to be free of gastrointestinal involvement by their tumors at exploratory laparotomy despite obstructing symptoms.

Diagnosis

After taking a careful history and performing a physical examination and obtaining blood for studies, patients admitted with obstructive symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, cramping abdominal pain, and abdominal distension) should undergo radiographic evaluation of the abdomen (supine and upright) and the chest with plain films. Patients with nondiagnostic plain abdominal films, atypical history and/or physical examination, or protracted courses without resolution of obstructive symptoms are candidates for further radiographic studies.

Many patients with obstructive symptoms may have indeterminate or equivocal plain radiographs, resulting in delayed management. In this patient population, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan is invaluable for diagnostic accuracy. In a recent study of 32 patients presenting with clinical suspicion of intestinal obstruction, abdominal CT had a higher sensitivity (93 vs. 77% and specificity (100 vs. 50%) than plain radiographs in diagnosing obstruction (26). Therefore, an abdominal CT scan should be considered for patients with an unclear diagnosis after plain films. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help distinguish between benign and malignant bowel obstructions (27).

Upper gastrointestinal radiographic contrast studies with small bowel follow through may be useful in further delineating a small bowel obstruction. Barium is generally more useful than water-soluble contrast agents for identifying a distal obstruction because gastrointestinal secretions do not dilute it. If barium remains in the small bowel, it does not become inspissated because the small bowel lacks the water absorptive capacity of the colon. However, a disadvantage of a barium study of the upper bowel is the need to fully cleanse the bowel of this agent before performing any subsequent radiographic studies, and therefore should be used only when the presence of an obstruction in the lower region has been ruled out. Perhaps the greatest utility of the upper gastrointestinal series is in patients with intermittent or partial small bowel obstruction.

For patients with suspected colonic obstruction or both small and large bowel obstruction, a barium enema can be quite useful in determining the presence and location of the large bowel obstruction. In patients with suspected mechanical large bowel obstruction by plain abdominal radiographs, contrast enemas have confirmed the diagnosis in most patients (28). However, as many as one third of patients will have free flow of contrast, ruling out mechanical

obstruction and raising the diagnostic possibility of pseudo-obstruction (28). A barium enema should never be attempted if a perforation is suspected and should be terminated promptly if the fluoroscopist detects an obstructing lesion. The colon can absorb water from the barium, which then becomes inspissated above a partially obstructing lesion, making subsequent colonic cleansing very difficult.

obstruction and raising the diagnostic possibility of pseudo-obstruction (28). A barium enema should never be attempted if a perforation is suspected and should be terminated promptly if the fluoroscopist detects an obstructing lesion. The colon can absorb water from the barium, which then becomes inspissated above a partially obstructing lesion, making subsequent colonic cleansing very difficult.

Management of Mechanical Obstruction

Overview

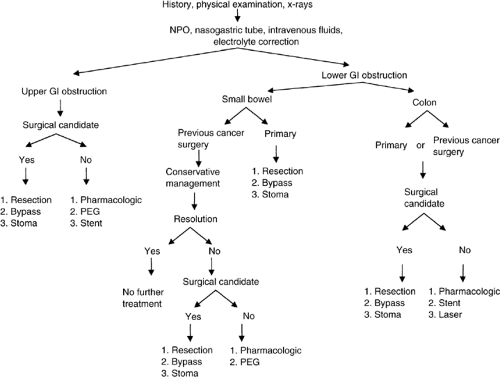

An algorithm describing the management of a suspected malignant mechanical bowel obstruction is presented in Figure 16.1. At initial presentation, a history, physical examination, and abdominal plain films should be performed routinely. Patients with obstruction are usually dehydrated and have electrolyte imbalances, owing to persistent vomiting and the inability to tolerate oral liquids. All patients should be aggressively hydrated intravenously and given nothing by mouth. A nasogastric tube should be placed in an attempt to relieve further vomiting and avoid possible aspiration. The electrolyte imbalance should be determined and corrected. Once the patient is adequately stabilized and hydrated, therapeutic strategies can be entertained.

When upper gastrointestinal obstruction is diagnosed, the etiology is generally secondary to a malignancy. If the patient is able to tolerate an operation, a resection and anastomosis or a gastroduodenal bypass should be performed. Less invasive procedures such as stenting or permanent tube decompression can be offered. In the largest reported series of patients undergoing surgical palliation (operative or endoscopic) for upper gastrointestinal obstruction (n = 151), 79% had symptom resolution (2). If the patient is not a candidate for surgery, pharmacologic palliation should be administered.

In the setting of small bowel obstruction, patients with a previously resected malignancy or abdominal surgery may be managed with a trial of conservative therapy. Often the obstruction will resolve as edema and inflammation of the distended bowel subside. If the obstruction resolves, no further treatment is warranted. If the obstruction persists for >3–7 days, patients able to tolerate an operation should undergo an exploratory laparotomy with the intention of reestablishing gastrointestinal continuity. The procedure may involve enterolysis for benign obstruction, resection, bypass, or a diverting ostomy for recurrent cancer. In one of the largest reported series of patients undergoing surgical palliation for small and large bowel obstruction (n = 97), 89% had resolution of symptoms (2). Patients with small bowel obstruction who are not candidates for surgery are best managed pharmacologically.

In contrast to small bowel obstruction, mechanical colonic obstruction does not usually resolve with conservative therapy

as this is rarely due to edema or inflammation. If the patient is able to tolerate surgery, a resection should be attempted when feasible. Patients with a large tumor burden can be managed either by bypass or stoma creation. Patients unable to tolerate a major surgical procedure can be managed by less invasive endoscopic ablative therapy, dilatation and stenting, or permanent tube decompression. These smaller procedures can be frequently done at the bedside or under local anesthesia.

as this is rarely due to edema or inflammation. If the patient is able to tolerate surgery, a resection should be attempted when feasible. Patients with a large tumor burden can be managed either by bypass or stoma creation. Patients unable to tolerate a major surgical procedure can be managed by less invasive endoscopic ablative therapy, dilatation and stenting, or permanent tube decompression. These smaller procedures can be frequently done at the bedside or under local anesthesia.

Figure 16.1. Management algorithm for malignant bowel obstruction. NPO, nothing by mouth; GI, gastrointestinal; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

Initial Management

In the absence of fever, leukocytosis, or peritonitis, patients with obstructive symptoms deserve a trial of conservative therapy. Patients need to be monitored with serial physical examinations (preferably by the same clinician) and with daily abdominal radiographs. In the patient with cancer, nasogastric decompression, intravenous hydration, and electrolyte replenishment results in spontaneous resolution of small bowel obstructions in 21% of patients (Table 16.1) in a mean of 3–7 days (17, 18). Approximately 40% of patients will need to be readmitted for conservative or surgical management of recurrent obstruction (Table 16.1). Bowel strangulation and gangrene are rare in these circumstances, occurring in 0–5% (17, 19), with the exception of one series in which it occurred in 24% of patients (18).

The choice of nasogastric tube or long intestinal tube (i.e., Miller-Abbott, Cantor, Baker) for decompression is individualized by the physician. Both tubes have been reported to have similar success in treating small bowel obstruction. A randomized study failed to identify the superiority of one tube over the other (32). The most common practice is to use the nasogastric tube because of its ease of placement and effectiveness in decompressing the upper gastrointestinal tract. It is more difficult to get long tubes into position (i.e., pass beyond the duodenum), but they can be effective in decompressing the more distal bowel. They may help delineate a site of obstruction through their failure to pass beyond the obstructed point or serve as a port for the instillation of radiographic contrast agents. Long tubes may also provide useful landmarks intraoperatively when faced with carcinomatosis and dense adhesions, locating a suitable segment of small bowel for bypass.

If, during the course of conservative therapy, the patient deteriorates or fails to improve after a clinically acceptable length of therapy, surgical therapy should be considered.

Surgical Management

Gastroduodenal Obstruction

When patients present with gastroduodenal obstruction, the goal is to reestablish gastrointestinal continuity and palliate the symptoms of obstruction. The surgical procedure should be performed with curative intent.

Ten to 20% of patients with pancreatic cancer, not undergoing a resection at initial surgery, eventually require a gastrojejunostomy for palliation of gastric outlet obstruction (6, 33). Hence, prophylactic gastrojejunostomy at the time of initial exploration has been advised for patients with unresectable obstruction (5, 6, 34). Effective palliation is not always achieved. Delayed gastric emptying may occur leading to significant postoperative morbidity (5). Recently, laparoscopic gastroenterostomy has been introduced for the treatment of gastroduodenal obstruction. The procedure can be performed safely with minimal operation times. Good palliation of nausea and vomiting can be expected (35).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree