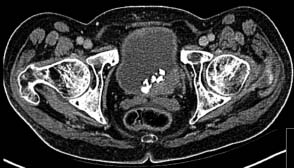

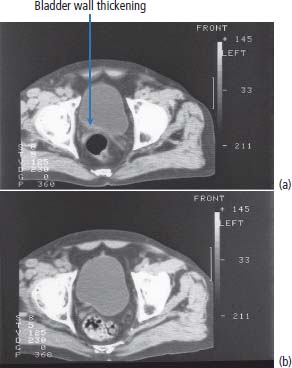

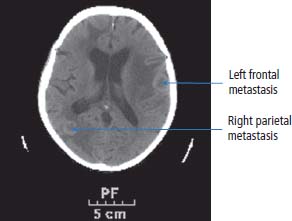

13 In 2011, 10,399 people were diagnosed with bladder cancer and 5081 died of the disease in the United Kingdom (Table 13.1). Worldwide more than one-third of a million people are diagnosed each year with bladder cancer and the global prevalence is estimated at 1.2 million. The highest incidence of bladder cancer is in industrialized nations of North America and Europe and in areas of endemic schistosomiasis in Africa and the Middle East. It is more than twice as common in men as in women. The most important cause of bladder cancer is cigarette smoking, which accounts for over a third of all cases in the United Kingdom. The relative risk of bladder cancer in smokers is four and is attributed to tobacco-derived carcinogenic aromatic amines. Genetic polymorphisms modify this risk. “Slow acetylators” have a polymorphism of the N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2) gene that reduces the enzymes activity, which includes the detoxification of aromatic amines. Thus, people with the slow acetylator phenotype are more susceptible to smoking-induced bladder cancer, an intriguing example of the interaction between nature and nurture (or genetic and environmental factors) in the pathogenesis of cancer. Workers in the dye, paint and rubber industries are also at increased risk of bladder cancer through a similar mechanism as these industries use aromatic amines (such as aniline, benzidine and naphthylamine). Worldwide, 210 million people are infected with Schistosoma haematobium and 700 million people live in endemic areas. After malaria, it is the second most important parasitic disease and may be eradicated by a single oral dose of praziquantel, costing about 50p. Chronic bladder infection by S. haematobium increases the risk of bladder cancer (Figure 13.1), especially the less common squamous cell cancer of the bladder, and is estimated to cause over 10,000 cases per year globally. This is thought to be due to chronic irritation and long-term urinary catheters have also been shown to increase the risk for similar reasons. There have been many developments in our understanding of the molecular biology of bladder cancer, and although these developments have not translated directly into treatment advances, they do provide significant prognostic information. Bladder tumours are thought to progress from a localized, superficial tumour to invasive and then metastatic disease. They are often multifocal. In an attempt to define the molecular events categorizing progression, it was originally noted that there was identical loss of heterozygosity in multifocal bladder tumours. This original description, however, of what was thought to be a primary genetic event in this cancer, has not been confirmed. Multiple loss of genetic material has been described, with the most common losses centred on chromosome 9q22, which is the site of a gene called patched (PTC). This is thought to be a tumour suppressor gene in basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma. The PTC protein is a transmembrane receptor that downregulates the Hedgehog signalling pathway that plays a central role in embryonic development in insects and vertebrates (see Chapter 32, p. 259). There are other sites of chromosomal loss, particularly within chromosomes 3, 7 and 17. This loss of material can be used to follow up patients with bladder cancer, using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) methodologies on urine cytology. Table 13.1UK registrations for kidney cancer 2010 By far the most important of the recent findings in bladder cancer, however, has been the observation of overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). This is reported in around 40% of the tumours of patients with bladder cancer. Overexpression correlates with a poor prognosis and treatments directed against EGFR may well have some future role as therapies for this malignancy. Figure 13.1 CT scan showing posterior wall bladder mass and calcification. The patient was from Egypt and had chronic schistosomiasis with an associated squamous cell cancer of the bladder. The initial symptoms include haematuria, dysuria and frequency of micturition. These symptoms are, unfortunately, sometimes treated with antibiotics by GPs for a period of time, prior to referral to a specialist. New urinary tract infections in older women should always be investigated actively, and symptoms occurring in a man should always be considered to be pathological and a referral made. Treating haematuria in a man with antibiotics without further investigation is negligent. There is of course a differential diagnosis, but one should have a very high index of suspicion of malignancy. Referral should be promptly organized to a specialist urological surgeon. The patient will be seen in an outpatient clinic. A careful history should be taken and an examination made. The patient’s symptoms should be investigated further by performing a blood count, renal function tests, liver function tests and bacteriological and cytological examination of urine, to examine for the presence of infection and malignancy. An intravenous pyelogram (IVP) or increasingly a CT urogram may be ordered to examine the urothelial tract radiologically or an ultrasound investigation carried out. These investigations should be organized promptly and the patient reviewed with the result within 2 weeks. A flexible cystoscopy is then generally organized and this takes place in the initial outpatient setting. If there is any suspicious appearance to the bladder, arrangements should then be made for a formal cystoscopy. The patient is anaesthetized for this procedure and the urethra and bladder carefully examined using a fibreoptic cystoscope. Any abnormal areas within the bladder should be biopsied together with areas of surrounding, apparently normal-looking bladder. The urologists at cystoscopy may describe a normal-looking bladder or the presence of a papilloma or solid tumour. The suspicious areas are treated by diathermy and the pelvis carefully examined in order to describe the clinical staging of the tumour. The tumour should then be examined pathologically and be given a grade according to differentiation. These grades are as follows: Lesions are further characterized pathologically by their microscopic appearance as either transitional cell carcinoma or squamous carcinoma. Approximately 90% of patients in the United Kingdom have transitional cell carcinomas. The remainder are squamous carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, or rarely lymphoma or small cell tumours. There may be squamous metaplasia present within a transitional cell carcinoma and this is thought to be indicative of a poor prognosis. Adenocarcinomas may arise in a urachal remnant or result from direct invasion from a colorectal primary tumour. The urachus, you will recall from embryology lectures, is the canal that drains the bladder in utero into the umbilical cord that subsequently becomes the median umbilical ligament. The tumour should also be staged according to the T (tumour), N (node) and M (metastatic categories) system (Table 13.2; see Figures 1.12 and 3.1). Table 13.2TNM staging of bladder cancer A prefix “p” is given to describe the pathological staging of the tumour (e.g. pT3a). The majority of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder present as superficial tumours. The first step in the diagnosis and management of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is cystoscopic transurethral resection of the bladder tumour (TURBT). After resection by diathermy at cystoscopy, approximately 60% of tumours will recur. The recurrence rate is greater where there are multiple tumours, associated carcinoma in situ or poorly differentiated tumours. For patients at low risk of recurrence, a single dose of intravesical mitomycin C may be administered following TURBT, whilst for those at high risk a course of intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) is given to reduce the recurrence rate. Maintenance therapy with BCG, given for up to 2 years, has been shown to prevent recurrence, but the side effects mean that only 30% patients complete the course of maintenance therapy. Cystoscopic surveillance following TURBT is advocated. The recommendation for follow-up is slightly controversial, but in most practices cystoscopy is performed 3-monthly until the patient is tumour-free and thereafter 6-monthly for 2 years and yearly for 3 years. Practice varies throughout the United Kingdom. The requirement for lifelong routine monitoring and treatment in bladder cancer made it the most expensive cancer in terms of total medical care expenditure at least in 2001 when this cost was estimated at US$ 100,000 from diagnosis to death. The authors of this book are impressed by the alacrity with which surgeons thrust out with knives advanced to excise bladders in patients with superficial bladder cancer. Many surgeons would view a recurrence-free survival of over 80% following cystectomy as a triumph of their surgical skills, but the truth (from several clinical trials) is that this recurrence-free survival is achieved by conservative treatment with intravesical BGC alone. The treatment of muscle-invasive carcinoma of the bladder is by surgery or radiation in those unfit for surgery. Radical cystectomy with urinary diversion is the preferred treatment for localized muscle-invasive bladder cancer and may in some cases be performed laparoscopically. Neoadjuvant cisplatin-containing chemotherapy before surgery has been shown to improve overall survival in two randomized controlled trials, whilst the use of post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy remains controversial. After cystectomy, patients must be nursed either in intensive care or in high-dependency beds. Continent bladders may be fashioned by the surgeon so that the patient does not require an ileostomy. Men are invariably rendered impotent by cystectomy. Little is known of the effects of cystectomy on female sexual function. There are well-known electrolyte disorders associated with ileostomies (chiefly dehydration and loss of sodium and potassium). Radical radiotherapy is generally given to a total dose of 6500 cGy over a 6-week period. Treatment should be given to the whole pelvis, focusing down upon the bladder towards the end of treatment, or may be given to the bladder alone. Some radiotherapists insist on treating pelvic nodes in addition to the bladder primary. This leads to added toxicity and is illogical. If there are metastases present in pelvic nodes, there is a very high chance that they will also be present in intra-abdominal nodes so irradiating pelvic nodes had no logical benefit. Radiotherapy can also be used to reduce haematuria in advanced disease if TURBT is unable to control this. During radiotherapy, the patient may get cystitis or proctitis. At the end of treatment, he or she may suffer from a small, shrunken bladder as a consequence of radiation fibrosis. Both cystitis and proctitis are common after radiotherapy to the bladder, occurring in up to 30% of patients. Adenocarcinoma of the bladder is thought to be relatively resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and as a consequence surgery is the main treatment option. Small cell bladder cancer and bladder lymphoma are managed with treatment regimens for small cell lung cancer and disseminated lymphoma, respectively. When bladder cancer has spread beyond the bladder, it is conventionally treated with chemotherapy. Recent advances in the treatment of this disease mean that new hope is now offered to patients with metastatic cancer. A number of different treatment schedules have been used for treatment. The standard treatment currently is combination therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin, chosen for efficacy and comparative lack of toxicity (Figure 13.2). Figure 13.2 (a) CT scan demonstrating thickening of the posterior bladder wall due to invasive bladder cancer and (b) the same image after four cycles of platinum-based combination chemotherapy showing a reduction in bladder wall thickening. Table 13.3 Bladder cancer survival The consensus view is that TURBT and intravesical therapy prevent the progression of superficial to locally advanced or metastatic disease in 40% of cases. Overall, however, approximately 30% of patients with superficial tumours develop invasive disease. The prognosis for bladder cancer declines steeply with stage of disease (Table 13.3 and Figure 3.1). During the terminal phases of illness, patients require specialist care for symptom palliation. The disease may spread to bone, lung or liver, and opiate analgesia or local radiotherapy may be helpful in easing symptoms (Figure 13.3). Figure 13.3 A man with a 3-year history of invasive bladder cancer treated with radical radiotherapy developed morning headaches and numbness of his right arm. His CT scan shown here shows two ring-enhancing metastases in the left frontal and right parietal regions with marked surrounding oedema. Case Study: The Albanian barber.

Bladder cancer

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Percentage of all cancer registrations

Rank of registrations

Lifetime risk of cancer

Change in ASR (2000–2010)

5-year overall survival

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Bladder cancer

2

5

11th

4th

1 in 110

1 in 40

-21%

-23%

50%

58%

Presentation

Staging and grading

T (primary tumour)

N (nodal status)

M (metastatic status)

Tis: Carcinoma in situ

N0: No lymph node involvement

M0: No evidence of metastases

Ta: Papillary non-invasive tumour

N1: Single regional lymph node involvement

M1: Distant metastases

T1: Superficial tumour, not invading

N2: Bilateral regional lymph node beyond the lamina propria involvement

T2: Tumour invading superficial

N3: Fixed regional lymph nodes muscle

T2a: Tumour invading superficial muscle

N4: Juxtaregional lymph node involvement

T2b: Tumour penetrating through superficial muscle

T3a: Invasion of deep muscle

T3b: Invasion through bladder wall

T4a: Tumour invading prostate, uterus or vagina

T4b: Tumour fixed to the pelvic wall

Treatment

Treatment of superficial bladder cancer

Treatment of invasive bladder cancer

Treatment of metastatic bladder cancer

Stage

TNM

5-year survival

0

Ta/Tis N0 M0

98%

1

T1 N0 M0

88%

2

T2 N0 M0

63%

3

T3 or T4a N0 M0

46%

4

T4b or N1-3 or M1

15%

Prognosis

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree