Biopsy of Musculoskeletal Tumors

Jacob Bickels

Yair Gortzak

Martin M. Malawer

BACKGROUND

Biopsy is a fundamental step in the diagnosis of a musculoskeletal tumor. It should be regarded as the final diagnostic procedure, not as a mere shortcut to diagnosis.

Biopsy should be preceded by careful clinical evaluation and analysis of the imaging studies.2,6,10,11 Diagnosis of a musculoskeletal lesion is based on this triad of clinical, pathologic, and imaging findings, and all three must coincide or else the diagnosis should be questioned.2,6

Most biopsies are technically simple to perform. Decisions regarding the indication for biopsy, the specific region of the lesion for biopsy, and the anatomic approach and biopsy technique, however, can make the difference between a successful biopsy and a catastrophe.

A poorly performed biopsy could become an obstacle to proper diagnosis and may impede the performance of adequate and safe tumor resection.

BIOLOGIC BEHAVIOR OF MUSCULOSKELETAL TUMORS

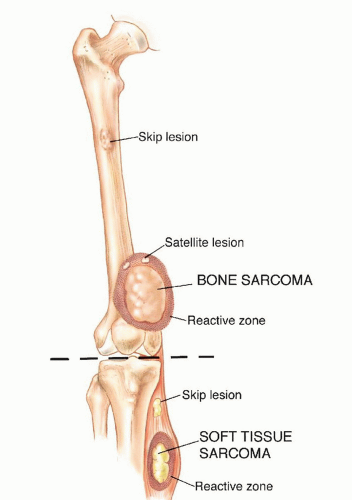

Tumors arising in bone and soft tissues share characteristic patterns of biologic behavior, stemming from their common mesenchymal origin and anatomic environment. Those unique patterns form the basis of the staging system and current treatment strategies.

Histologically, sarcomas are categorized as being low, intermediate, or high grade based on tumor morphology, extent of pleomorphism, atypia, mitosis, and necrosis. Grading represents their biologic aggressiveness and correlates with the likelihood of metastases.

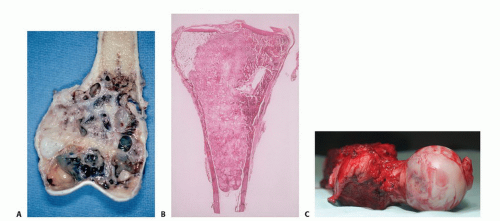

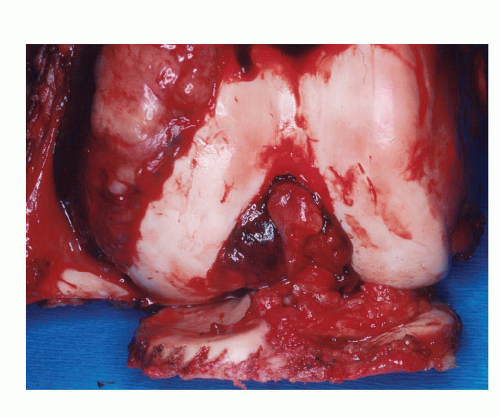

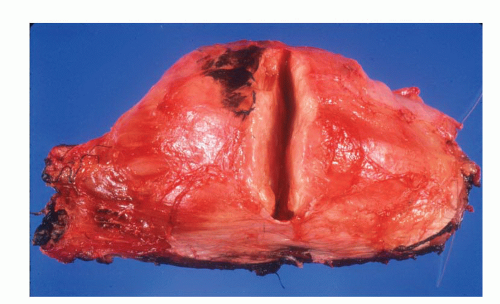

FIG 1 • A cut through a high-grade soft tissue sarcoma showing its thin pseudocapsule composed of compressed tumor cells and a fibrovascular zone of reactive inflammatory response.

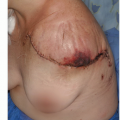

Sarcomas form a solid mass that grows centrifugally with the periphery of the lesion being the least mature part. Unlike the true capsule that surrounds benign lesions, which is composed of compressed normal cells, sarcomas are generally enclosed by a reactive zone or pseudocapsule. This consists of compressed tumor cells and a fibrovascular zone of reactive tissue with a variable inflammatory component that interacts with the surrounding normal tissues (FIG 1).

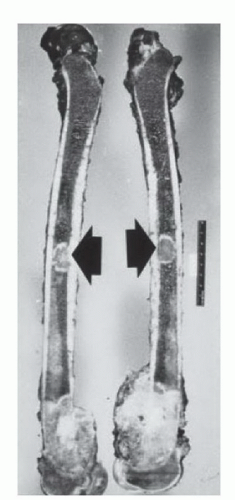

In addition, these cells may break through the pseudocapsule to form metastases (“skip metastases”) within the same anatomic compartment in which the lesion is located. By definition, these are locoregional micrometastases that have not passed through the circulation (FIGS 2,3 and 4). This phenomenon

may be responsible for local recurrences that develop in spite of apparently negative margins after a resection. Although low-grade sarcomas regularly interdigitate into the reactive zone, they rarely form tumor skip nodules beyond that area.

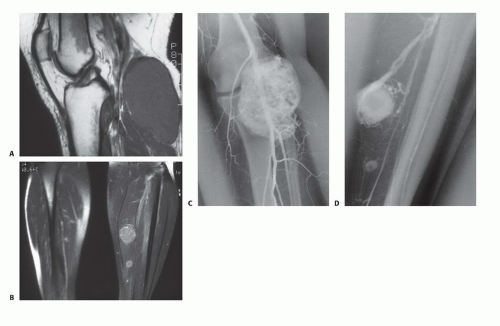

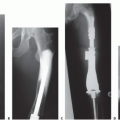

FIG 3 • High-grade sarcomas may break through the pseudocapsule to form skip metastases within the same anatomic compartment. Skip metastases (arrows) from an osteosarcoma of the distal femur.

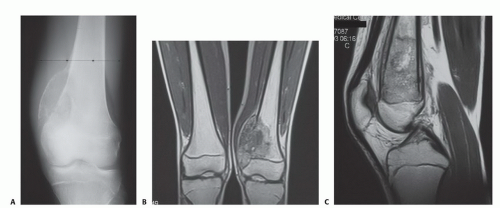

Sarcomas respect anatomic borders. Local anatomy influences tumor growth by setting natural barriers to extension of the lesion. In general, sarcomas take the path of least resistance and initially grow within the anatomic compartment in which they arose. In a later stage, the walls of that compartment (either the cortex of a bone or aponeurosis of a muscle) are violated, and the tumor breaks into a surrounding compartment (FIGS 5 and 6).

Most bone sarcomas are bicompartmental at the time of presentation; they destroy the overlying cortex and extend directly into the adjacent soft tissues (FIG 7).

Soft tissue sarcomas may arise between compartments (extracompartmental) or in an anatomic site that is not walled off by anatomic barriers such as the intermuscular or subcutaneous planes. In the latter case, they remain extracompartmental and only at a later stage do they break into the adjacent compartment (FIG 8). Carcinomas, on the other hand, directly invade the surrounding tissues, irrespective of compartmental borders (FIG 9).

Unlike carcinomas, bone and soft tissue sarcomas disseminate almost exclusively through the blood. Hematogenous spread of extremity sarcomas is manifested by pulmonary involvement in the early stages and by bony involvement in later stages (FIG 10).

FIG 7 • Plain radiograph (A) and magnetic resonance images (B,C) showing a classical osteosarcoma of the distal femoral metaphysic breaking through the medial cortex into the adjacent soft tissues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|