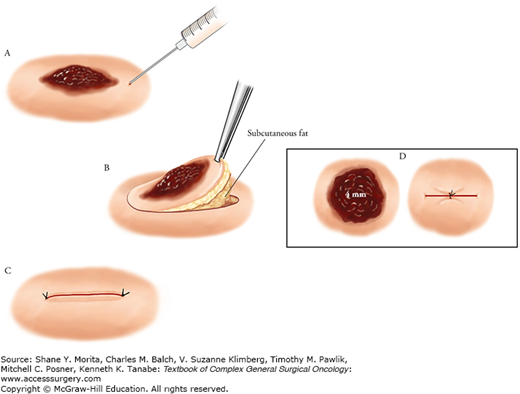

A skin lesion that is suspicious for melanoma is best removed by excisional biopsy with a 1- to 2-mm clinical lateral margin and a deep margin into the subcutaneous fat, underneath all epithelial appendageal structures.1 This can be performed on most lesions up to 1.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 13-1). The biopsy scar should be oriented to be compatible with a subsequent wide local excision should the lesion prove to be melanoma. On the extremities a longitudinal or oblique incision is preferred. On the trunk or the head and neck the biopsy should be oriented parallel to the skin lines. A full-thickness biopsy should be undertaken in order to accurately interpret the maximum tumor thickness, the presence or absence of ulceration, and the level of invasion.1

FIGURE 13-1

Technique of excisional biopsy. A. Injection of local anesthetic around the lesion. B. Full-thickness excion of the lesion with a 1-mm margin. C. Closure of the biopsy incision. D. Full-thickness biopsy excision of the lesion with a 6-mm punch biopsy instrument and closure with a single suture. (Reproduced with permission from Balch CM, Houghton AN, Sober AJ, et al. Cutaneous Melanoma. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2003.)

An incisional biopsy using either a 6-mm punch instrument or a scalpel (removing a small fusiform ellipse) may be appropriate for lesions that are large or located at a difficult anatomic site where one would want to know the diagnosis before removing the entire lesion (Fig. 13-1). The biopsy should be taken from the most raised or the most darkly pigmented area, but since it removes only part of the tumor, a repeat biopsy may be necessary if the histological diagnosis does not agree with the clinical impression. An incisional biopsy involves removal of a portion of a skin lesion, in which the lateral margins are incomplete, and therefore, by definition, positive, but the deep margin should be in the subcutaneous fat, underneath all epithelial appendageal structures.2 Final determination of the tumor thickness cannot be made until the entire lesion has been excised and examined by the pathologist. For suspicious lesion beneath nailbeds, the biopsy approach is more problematic. Although digital tumors usually arise from the proximal nail fold from which the biopsy must be procured, biopsies of subungual pigmented lesions necessitate splitting of the nail plate.

A shave biopsy involves removal of a portion of a skin lesion for diagnosis, using a scalpel or a sharp razor blade, in which the deep margin of resection is within the dermis. However, if the lesion does prove to be a melanoma, a prior shave biopsy may prevent accurate assessment of Breslow thickness. Shave biopsies may be considered for small flat lesions where the likelihood of melanoma is considered to be low, but are inappropriate when a melanoma is suspected, because an incomplete Breslow depth measurement could result.3 However, it is a useful biopsy technique when performed by an experienced clinician in the specific setting in which melanoma in situ is being considered in the differential diagnosis along with, perhaps, a benign lentigo or flat seborrheic keratosis.1

Once a lesion is diagnosed as an invasive melanoma or a melanoma in situ, surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment. There is some evidence that there may be early intralymphatic metastases (also termed microsatellites) around an invasive melanomas, and this is the primary rationale for widely excising melanomas with a margin of normal appearing skin and underlying subcutaneous tissue.4,5 The goals of surgical treatment are to remove all the melanoma cells at the primary site in order to provide durable local disease control for all patients, even when the likelihood for distant relapse is high, and to affect a cure in those patients who do not harbor occult metastatic disease.2

Thirty years ago, the standard of care for wide excision of a melanoma was a 4- to 5-cm radial margin of skin. However, a series of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has since shown conclusively that excising melanomas with 1- to 2-cm margins is safe, and that the actual margin selected is determined by the tumor thickness and the presence or absence of ulceration. These studies have provided level I evidence that supports the current guidelines for the surgical approach to peripheral margins. These trials tested the following concepts:

Local failure is a function of both biology of the primary tumor and extent of surgical excision.

Thin melanomas have a low risk for recurrence and narrow (1 cm) margins are safe.

Thicker and/or ulcerated melanomas are associated with a higher incidence of clinically occult intralymphatic metastases that can be removed with wider excisions, in turn lowering the risk of subsequent local and/or regional recurrences.

Increased rates of local and regional failure can have an impact on survival.

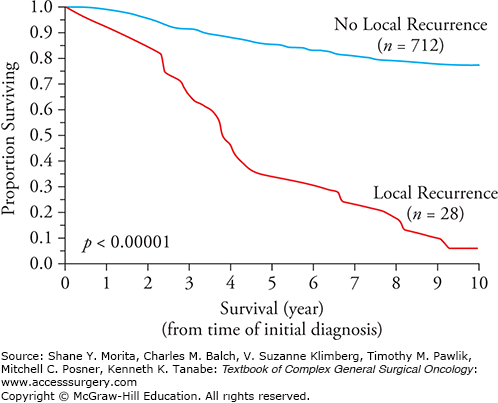

A local recurrence that occurs months or years after wide excision of a melanoma is an uncommon event, and local recurrence is widely viewed as a benchmark of surgical quality control. It is most likely a manifestation of residual microsatellites in the immediate area left behind after surgery.4 In contrast to local recurrences of basal or squamous cell carcinomas that are not life threatening, a local recurrence of melanoma is associated with a very poor overall survival similar to that of intralymphatic metastases (in-transits or satellites) (Fig. 13-2). This is especially the case if there are concomitant regional lymph node metastases. It is likely that local recurrences are, in fact, a manifestation of intralymphatic disease, not of retained primary melanoma cells that grow back with an unusually aggressive biological capacity for metastases. This explanation provides a much more logical rationale for performing a wide excision of normal appearing skin surrounding a primary melanoma, that is, to excise microsatellite metastases that are usually not detected without serial sectioning of the primary melanoma and adjacent skin.4

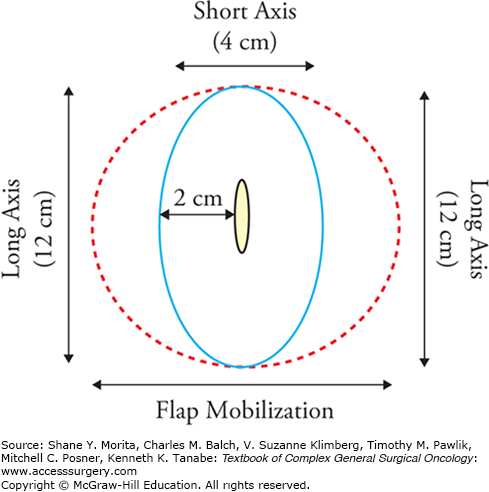

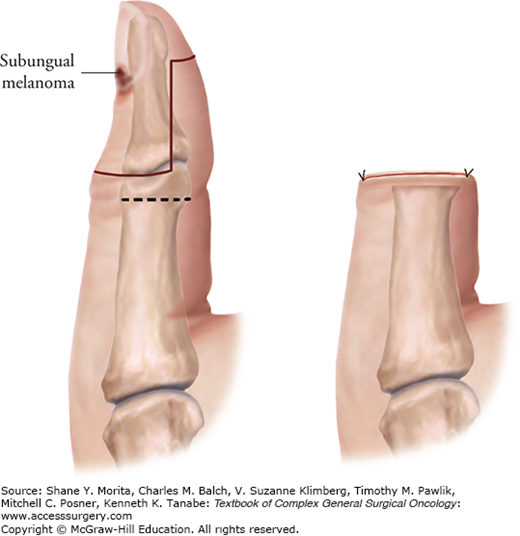

The suggested surgical technique for excising primary invasive melanomas with a 1- to 2-cm radial margin of skin is shown in Figure 13-3. Some locations, such as the ear, nose, and digits may not lend themselves anatomically to a full 2-cm radial excision margin.6 This is especially true on the thumb, where it is important to maintain adequate function after a partial amputation (Fig. 13-4). Further details on excision of primary melanomas and closures, especially in difficult areas, are provided elsewhere.6,7

There have been six RCTs involving 4233 patients in which narrow resection margins have been compared to more traditional wide resection margins, with robust 5- to 16-year median follow-up periods.8–16 The definitions of narrow and wide margins are heterogeneous between the studies, varying from 1 to 2 cm for narrow margins and 3 to 5 cm for wide margins. None of these studies demonstrated a significant difference between the narrow and wide resection margins in regard to disease-free survival or overall survival.13,17 The results of the six RCTs are described below and summarized in Table 13-1.

Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Narrow Resection Margins to Wide Marginsa

| Study | Median Thickness (mm) | Definition of Narrow Margin (cm) | Definition of Wide Margin (cm) | 5-Year DFS for Narrow Margins | 5-Year DFS for Wide Margins | 5-Year OS for Narrow Margins | 5-Year OS for Wide Margins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French (2003) | 3.1 | 2 | 5 | 85% (10 years) | 83% (10 years) | 93% | 90% |

| Intergroup (2001) | 1.8 | 2 | 4 | 75% | 80% | 76% | 82% |

| Swedish (2000) | 1.2 | 2 | 5 | 81% | 83% | 86% | 89% |

| WHO (1998) | 1.0 | 1 | 3 | 82% (8 years) | 84% (8 years) | 90% (8 years) | 90% (8 years) |

| BAPS/MSG (2004) | 3.0 | 1 | 3 | 55% (NR extrapolated from graph) | 48% (NR extrapolated from graph) | 68%b (NR extrapolated from graph) | 70%b (NR extrapolated from graph) |

| Swedish (2011) | 3.1 | 2 | 4 | 56% | 56% | 65% | 65% |

The WHO Melanoma Program published the first randomized trial addressing excision margins in patients with melanoma.15,16 Its surgical protocol (Trial #10) compared 1-cm versus 3-cm radial margins of excision in 612 patients who had melanomas with a thickness of 2.0 mm or less. This group of patients was selected because the predicted risk of local recurrence was low, and therefore it was presumed safe to test a more conservative margin of excision. The trial was stratified and subsequently analyzed according to thickness ranges (<1 mm and 1 to 2 mm). Long-term results of this trial demonstrated that a 1-cm margin of excision was safe primary treatment for the thickness subsets evaluated, as no difference in survival rates was observed relative to the group undergoing excision with 3-cm radial margins.

Rates of local recurrence were also not statistically different overall between the two treatment groups. For the subset of patients who had lesions less than 1 mm in thickness, no local recurrences had been encountered at the time of the first two reports of this trial, regardless of the extent of surgical margin.15,16 By the time of the updated summary report in 1998, one patient who had a lesion less than 1 mm in thickness, who was treated by a 3-cm excision, had local recurrence.18 A total of seven patients in the 1- to 2-mm thickness subset had local recurrences; five of these seven were treated with the narrower 1-cm excision. Altogether 5 local recurrences in 119 patients (4.5%) were observed in patients who had primary melanomas in the 1.1- to 2.0-mm thickness range and who had a 1-cm margin of excision (N. Cascinelli, personal communication, 2001).

The study illustrated that the incidence of local recurrence is extremely low in this group and is primarily a function of primary tumor thickness but may also be influenced by width of excision. Because these events were so infrequent, any impact on overall survival could not be assessed. The authors concluded that a 1-cm margin of excision for melanomas less than 2 mm in thickness is safe and should be standard.

The Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial enrolled 740 patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas (i.e., 1.0 to 4.0 mm) and randomized the majority of them to undergo either 2- or 4-cm resection margins.8,11,19 Two eligibility groups were established and stratified according to tumor thickness (1 to 2 mm, 2 to 3 mm, and 3 to 4 mm), anatomic site (trunk, head and neck, and extremity), and ulceration. Eligibility in group A (n = 468) was confined to those patients who had melanomas located on the trunk or proximal extremity to ensure that the more radical 4-cm margin could be carried out if they were randomly assigned to receive such a treatment. The remaining patients, designated group B (n = 272), included those who had either head and neck or distal extremity lesions, all of whom underwent a 2-cm excision. All patients were also randomized to receive either an elective lymph node dissection (ELND) or observation following wide local excision.8 More than 94% of the patients entered were eligible and evaluable. As of the latest report, 92% of patients had been followed for at least 5 years or until death. This is now a mature database with median and longest follow-up times of 10 and 16 years, respectively.19 The overall local recurrence rate was 3.8% and did not vary based on the excision margin (i.e., 2 or 4 cm). The local recurrence rate increased in those patients with increased tumor thickness, or in the presence of an ulcerated melanoma, or when the melanoma occured in the distant extremities/head and neck anatomic areas (Table 13-2).

Intergroup Randomized Study Local Recurrence Rates Based Upon Tumor Thickness, Ulceration status, and Anatomical Site (Local Recurrence Rate: 3.8% overall; p = 0.001)a

| Local Recurrence Rates Based on Melanoma Thickness and Anatomic Site | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma Thickness (n) | (all patients) | Trunk/Proximal Extremity | Head/Neck/Distal Extremity |

| 2.3% | 1.0% | 3.8% |

| 4.2% | 4.6% | 5.6% |

| 11.7% | 4.1% | 23.1% |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree