Fig. 12.1

Plain abdominal radiograph of a patient with gallstone ileus. Note the presence of pneumobilia depicted in the circled area. Gallstones may not be present due to lack of calcium composition

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has become the initial diagnostic test of choice in patients with suspected biliary disease. The test can be rapidly performed at the patient’s bedside and does not require the use of radiation. Ultrasound is highly accurate for identifying stones that are ≥5 mm in size (>96 %) [31]. In order to diagnose gallstones, there must be demonstration of echogenicity, production of posterior acoustic shadowing, and mobility of the calculi (see Fig. 12.2). False-negative studies may be seen when the examination is performed by an inexperienced sonographer, there is a large amount of bowel gas, or the stones are small (<3 mm) or pigmented [31, 33, 34]. Examining the gallbladder with the patient in multiple different positions can reduce the rate of false-negative exams.

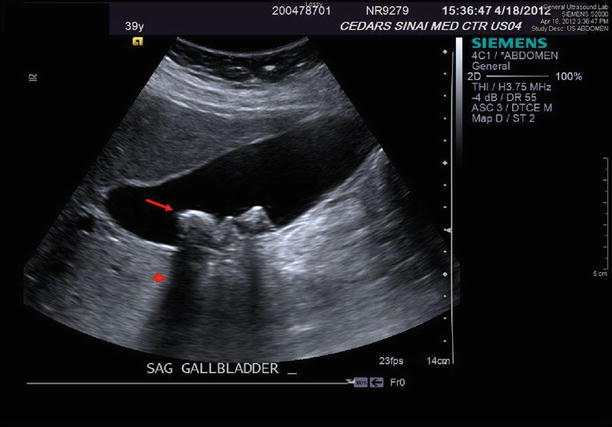

Fig. 12.2

Abdominal ultrasound documenting cholelithiasis. Note the hyperechoic stones (arrow) and posterior acoustic shadowing (arrowhead)

Ultrasonography is also helpful in establishing the diagnosis of acute and chronic cholecystitis. In the setting of acute cholecystitis, the most reliable finding is a sonographic Murphy’s sign which is tenderness over the gallbladder with transducer pressure. This finding is 87 % specific for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis and has a positive predictive value of 92 % when stones are also visualized [35]. The Murphy’s sign may not be elicited in patients that are immunosuppressed, obtunded, and recently medicated or have denervated gallbladders (i.e., diabetics or gangrenous cholecystitis) [31]. Other findings that are indicative of acute cholecystitis include gallbladder wall thickening (>3 mm), which is present in 50 % of cases, as well as the presence of pericholecystic fluid (see Fig. 12.3) [31, 35]. It should be noted, however, that these findings alone are nonspecific and may occur with adjacent right upper quadrant pathology. The ultrasonographic diagnosis of chronic cholecystitis can also be suggested by nonspecific gallbladder wall thickening due to fibrosis with resultant contraction and near obliteration of the gallbladder lumen producing the “double-arc” sign [36].

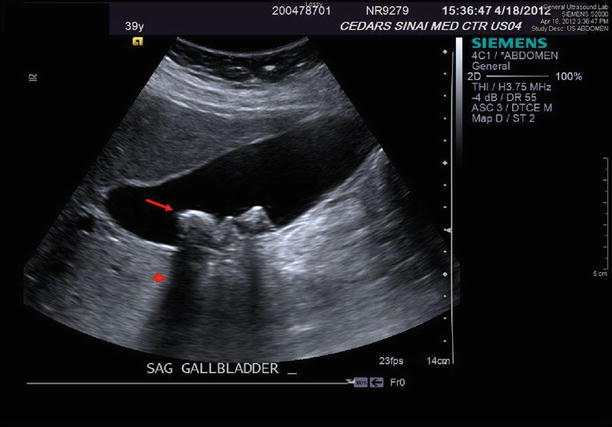

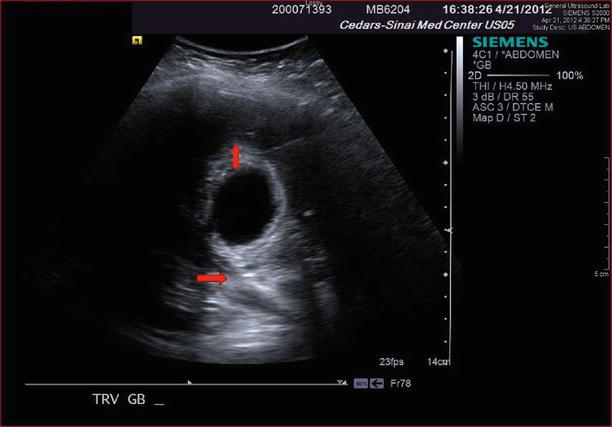

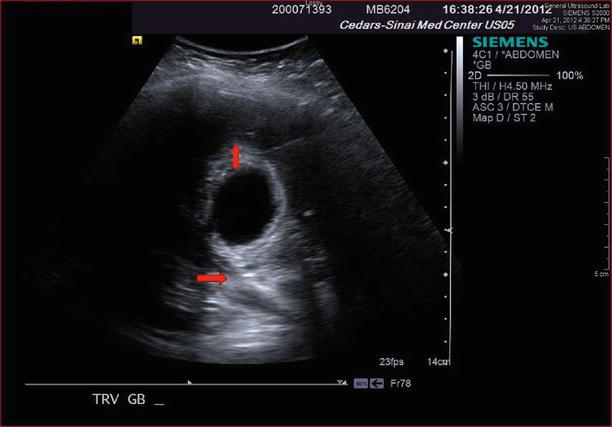

Fig. 12.3

Ultrasound depicting the findings of acute cholecystitis. Note the presence of gallbladder wall thickening (double arrowhead) and pericholecystic fluid (single arrow)

Ultrasound examination of the right upper quadrant is also the initial imaging study of choice to evaluate for choledocholithiasis. It allows for quick assessment of the extrahepatic and intrahepatic bile duct size and continuity. The extrahepatic common bile duct is routinely measured at the level of the right hepatic artery and should not exceed 6 mm in diameter, while the upper limit for normal diameter of the intrahepatic bile ducts is 2 mm [34]. With adequate sonographer experience, the level of biliary obstruction can be identified in 92 % of patients, and overall sensitivity for choledocholithiasis can reach 75 % [34]. It is important to emphasize that choledocholithiasis can also be present in the absence of biliary ductal dilation in 25–33 % of cases [37]. When this occurs or when stones are less than 5 mm in diameter and overshadowed by bowel gas, the sensitivity of ultrasound is considerably lower. Endoscopic ultrasonography is more sensitive than transabdominal ultrasound for detecting choledocholithiasis (96 %) and should be considered in select cases of presumptive biliary obstruction (i.e., suspected malignancy) due to its more invasive nature [38].

Biliary Scintigraphy (HIDA)

Biliary scintigraphy involves the intravenous administration of radiolabeled technetium iminodiacetic acid which is taken up by the hepatic parenchyma and excreted into the bile with eventual uptake in the gallbladder. The use of hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) has largely declined into a second-line test for calculous biliary disease due to its increased expense, amount of time needed to complete the study, and the use of ionizing radiation. HIDA is diagnostic for acute cholecystitis when there is non-visualization of the gallbladder 60 min after administration of the technetium (see Fig. 12.4). This test can be carried out in a delayed fashion for up to 4 h; non-visualization during this extended time frame is considered consistent with chronic cholecystitis [39]. Scintigraphy has excellent diagnostic sensitivity (>95 %), particularly in nonhospitalized patients that are much less likely to have false-positive imaging studies [39]. False-positive studies may be seen in up to 30–40 % of patients that are hospitalized for a reason other than abdominal pain, which is a common scenario in the elderly population [40]. Reasons for false-positive exams include prolonged fasting, cholestasis secondary to hepatic disease, or prolonged parenteral nutrition [31]. HIDA can also play a role in diagnosing postoperative biliary complications such as a cystic duct stump leak or biliary motility disorders. However, due to the previously mentioned limitations, differences in cost, and radiation exposure, ultrasonography should be considered as the initial diagnostic imaging test to diagnose cholelithiasis.

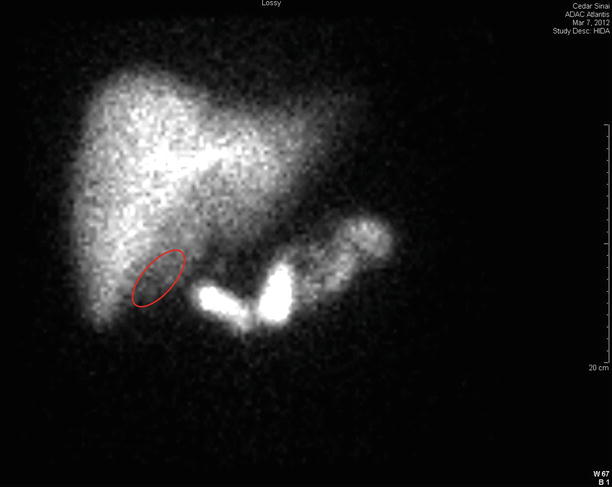

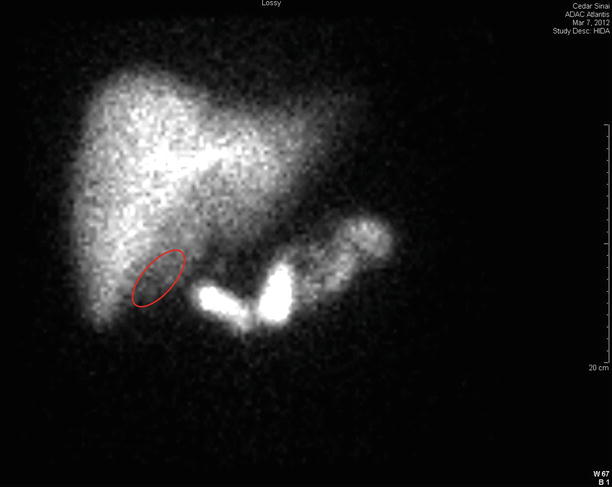

Fig. 12.4

Example of a positive HIDA scan. Note the absence of radioactivity in the area of the gallbladder fossa (highlighted oval)

Computerized Tomography

Computerized tomography (CT) has variable sensitivity in detecting gallstones secondary to the variable amount of calcification present and thus is also a second-line imaging study for biliary calculi. Calculi that are predominantly composed of cholesterol will be more difficult to identify due to their similar radiographic density as the surrounding bile. CT has similar sensitivity as compared to ultrasonography in identifying choledocholithiasis (75–80 %) (see Fig. 12.5) [31, 38] and can give information regarding ductal anatomy. CT imaging is most useful in demonstrating gallbladder size, wall thickness, and surrounding inflammatory changes associated with acute cholecystitis making it highly specific (99 %) for this particular diagnosis (see Fig. 12.6) [41]. In the setting of suspected malignancy of the head of pancreas or choledochus, CT is the diagnostic image of choice because it allows assessment of not only the gallbladder but adjacent organs such as the liver and the porta hepatis, identification of lymphadenopathy, or pancreaticoduodenal pathology [42]. In the elderly patient with preexisting renal disease, diabetes, or certain medications (i.e., ACE inhibitors, NSAIDs, or metformin), caution should be taken with administering IV contrast as this can precipitate acute kidney injury or exacerbate chronic kidney disease. The nephrotoxicity of the contrast can be reduced with administering intravenous fluid to correct hypovolemia, sodium bicarbonate, and/or Mucomyst. Isoosmolar contrast should also be infused for the dynamic phase of scan [43].

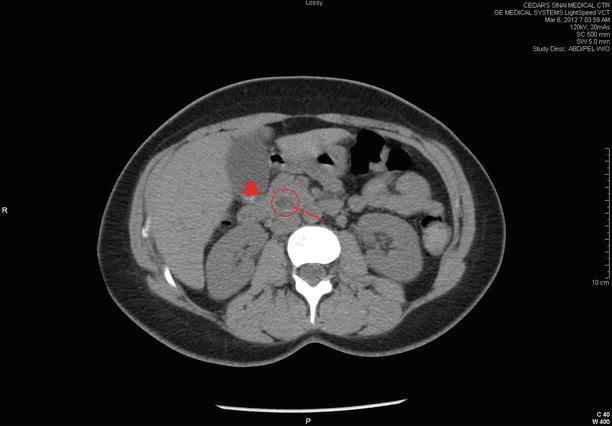

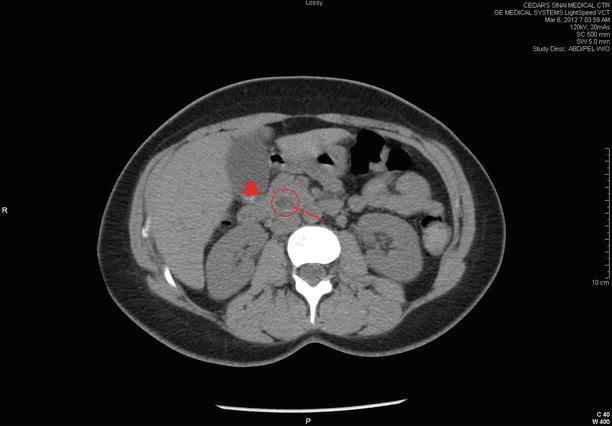

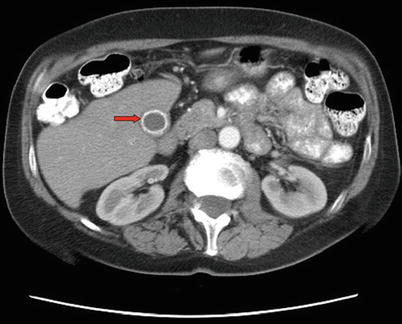

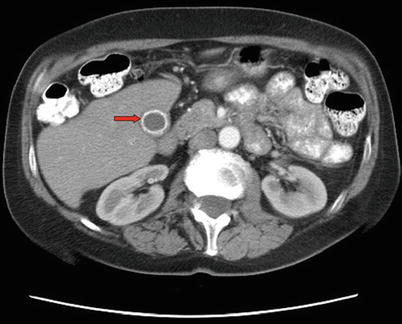

Fig. 12.5

CAT scan of the abdomen showing a stone (thin arrow) in a dilated common bile duct (circled) along with cholelithiasis (thick arrow)

Fig. 12.6

CAT scan of the abdomen showing evidence of acute cholecystitis. Notice distention of the gallbladder (asterisk) with surrounding pericholecystic fluid

Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Cholangiopancreatography (MRI/MRCP)

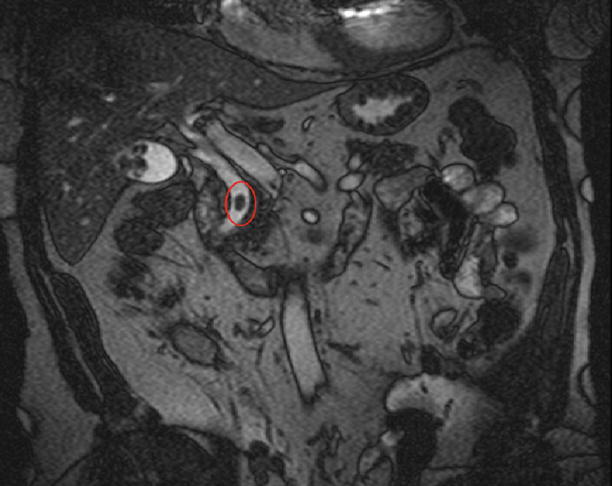

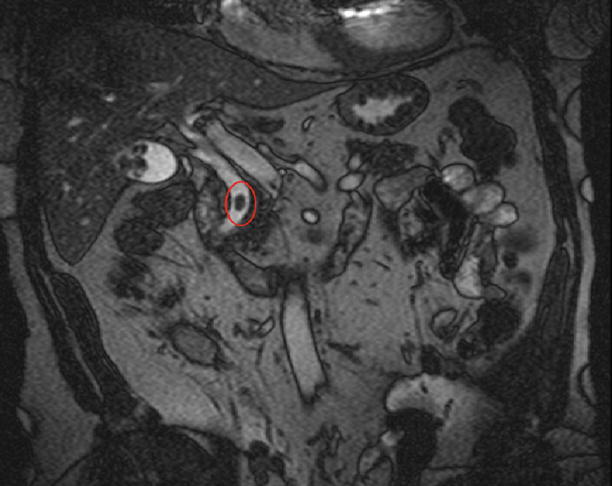

MRI, though not frequently used as an initial imaging test, has excellent ability to identify gallstones due to the sharp contrast in signal intensity between bile and stones on T2-weighted images [44]. The resolution with MRCP allows stones as small as 2 mm in diameter to be identified in both the gallbladder and common bile duct (see Fig. 12.7). The sensitivity (81–100 %) and specificity (85–99 %) of MRCP for choledocholithiasis are equivalent to that for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) but without the inherent risk associated with invasive procedures [45]. However, MRCP is less sensitive for diagnosing microlithiasis, pneumobilia, or calculi in the peri-ampullary region [46]. MRI can also be useful in those with malignant disease as it images the gallbladder wall, liver parenchyma, and biliary tree with high resolution. Unfortunately, elderly patients with dementia or claustrophobia do not tolerate MRI scanning due to the tight confines of the imaging magnet. Also those with a pacemaker or defibrillator device may also not be candidates for MRI, though certain devices have not malfunctioned after imaging [47].

Fig. 12.7

T2-weighted MRCP showing a large stone in the common bile duct (highlighted oval)

Invasive Imaging

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Advances in endoscopic techniques and training during the past three decades have made ERCP widely available. It is the gold standard for the diagnosis of the majority of bile duct pathology. However, due to its invasive nature and improvements in the aforementioned noninvasive imaging techniques, ERCP has evolved into more of a planned therapeutic procedure rather than the preferred imaging study for the purpose of obtaining a diagnosis. But those patients presenting with symptomatic choledocholithiasis (i.e., Charcot’s triad or Reynolds’ pentad) or with documented common duct stones on imaging studies are clearly potential candidates for ERCP (see Fig. 12.8). Predicting which asymptomatic patients will ultimately require ERCP is more difficult, but advanced age (>55), hyperbilirubinemia (>1.8 mg/dL), and common bile duct dilation have all been shown to increase the probability of a therapeutic ERCP [48]. The success rate of ERCP for accessing the common bile duct is near 98 % in all patients [49]. A complicating factor in older patients is the presence of a duodenal diverticulum which is found in 20 % of autopsies and on 5–10 % of upper gastrointestinal series. When the diverticulum is juxtapapillary, the endoscopist will frequently have difficulty with safely cannulating the ampulla. Thus, the success rate of ERCP for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes in the elder is less than 98 %. Transduodenal imaging of the biliary tree is associated with a number of well-described complications, with the most common being acute pancreatitis. The incidence of post-procedure pancreatitis ranges between 5 and 10 %. Despite the possibility of post-ERCP complications, elderly patients appear to tolerate the procedure as well as their younger counterparts [50].

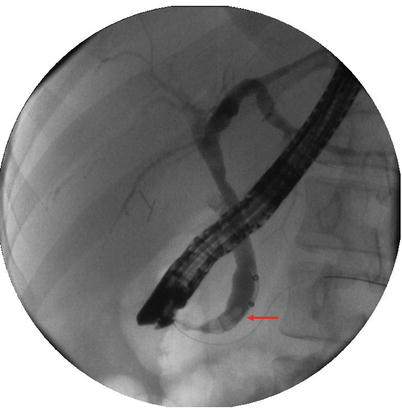

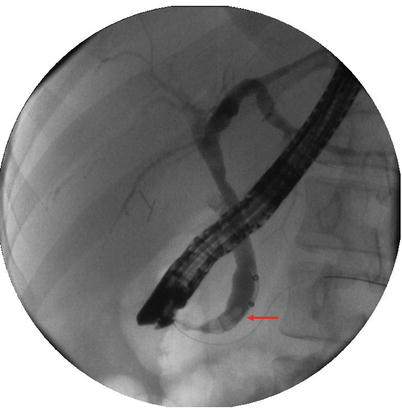

Fig. 12.8

An ERCP demonstrating a dilated common bile duct with multiple stones (arrow)

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiography

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) involves the passage of a needle into the liver parenchyma under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance to access the intrahepatic biliary radicles for diagnostic and/or therapeutic purposes (Fig. 12.9). This technique was initially introduced in 1979 and remains a valuable option for treating biliary pathology when ERCP is either unavailable or unsuccessful, particularly in the critically ill population [51, 52]. PTC can be used to successful treat acute cholecystitis (cholecystostomy tube), cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, or surgically related biliary complications with a high success rate. It should be noted that PTC carries a greater complication risk than ERCP because the catheter traverses the hepatic parenchyma to access the biliary tree; there is a known risk for hemorrhage, septic shock from bacterial translocation, or bile peritonitis.

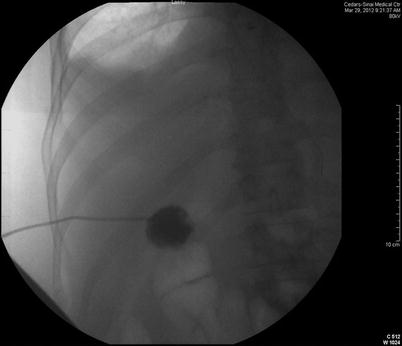

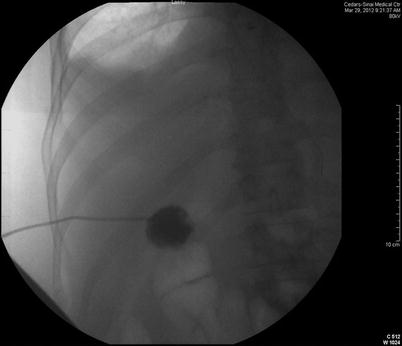

Fig. 12.9

PTC done under fluoroscopy for acute cholecystitis

Benign Calculous Diseases

Acute Calculous Cholecystitis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The pathophysiology of acute cholecystitis is initiated when a calculus obstructs the cystic duct. Initially, the patient will experience epigastric pain which will localize to the right upper quadrant when the inflammatory process involves the parietal peritoneum. Patients will frequently experience nausea and vomiting. There may be pain referred to the back and right shoulder. The majority of patients will recall prior episodes of similar pain that were consistent with biliary colic. Acute cholecystitis is the initial presentation of gallstone disease in 15–20 % of patients [53]. In addition to the findings on physical examination, there may also be signs of systemic inflammation including fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis. Laboratory studies that may be abnormal include elevation of C-reactive protein, mild elevation of serum bilirubin, and transaminases (<500 IU/L). If the serum bilirubin is greater than 2 mg/dL, particularly the conjugated form, or serum transaminases are >500 IU/L, choledocholithiasis should be suspected as the incidence of concomitant common bile duct calculi in the elderly is quite high (10–20 %) [49]. It is important to emphasize, however, that the typical presentation in the elderly patient is often the exception rather than the rule as a significant percentage will have no fever, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, and normal laboratory findings [25, 54, 55]. In some cases, the only presenting symptom of acute cholecystitis will be a change in mental status or poor oral intake [55, 56]

When the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is suspected, abdominal ultrasonography is the initial imaging test of choice. A sonographic Murphy’s sign combined with the presence of stones, gallbladder wall thickening, and pericholecystic fluid confirms the diagnosis. In cases where the diagnosis is less clear, or when there are no stones visualized, a HIDA scan may be useful. The findings on CT scan of acute cholecystitis as previously described should also be reviewed for possible additional pathology.

Treatment of Acute Calculous Cholecystitis

Ongoing cystic duct obstruction causes inflammation and can lead to bacterial infection in the bile as well as ischemia of the gallbladder wall. Initial supportive measures such as bowel rest (NPO) to reduce stimulation of the gallbladder, intravenous fluid hydration, and analgesics are appropriate. The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines recommend empiric antimicrobial therapy in cases of clinically suspected infection [57]. Selection of an antimicrobial(s) should provide coverage of Enterobacteriaceae species. Appropriate antibiotic choices for uncomplicated cholecystitis include second- and third-generation cephalosporins or a combination of fluoroquinolones with metronidazole [57]. For patients who present with severe sepsis or those that are considered high risk (i.e., elderly, diabetics, or immunocompromised), broad-spectrum antibiotics such as piperacillin/tazobactam or aminoglycosides should be considered [57].

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the operative intervention of choice due to the low morbidity compared to open surgery [58, 59]. The techniques of laparoscopic cholecystectomy are beyond the scope of this chapter and can be found elsewhere [60]. Elderly patients frequently present with complicated acute cholecystitis (i.e., gangrene, perforation, or emphysematous cholecystitis) all of which are more likely to require emergent surgical intervention with subsequently increased morbidity and mortality [6, 25]. The traditional management of initial nonoperative with supportive measures and antibiotics during the acute inflammatory period followed by delayed surgical cholecystectomy 6 weeks later may still be appropriate for patients with comorbidities associated with increased perioperative risk. However, the recurrence rate of acute cholecystitis can be as high as 30 % over a 3-month waiting period [61, 62].

Two recent systematic reviews of the literature compared outcomes for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (within 24–72 h) compared to delayed operation (6–12 weeks after initial presentation) [63, 64]. Both meta-analyses found that there were no significant differences in conversion rates to open procedures, incidence of common bile duct injuries, or postoperative complications. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is also associated with a shorter hospital length of stay and lower total hospital cost [63]. It should be noted that in one of the meta-analysis, the incidence of bile leaks was higher in the early cholecystectomy group (3 % vs. 0 %) [63]. Also, due to the small number of total patients in these pooled randomized trials (451), the incidence of common duct injury could easily be over or underrepresented in either group due to the low overall incidence of this complication (0.4–0.6 %) [65]. Despite these limitations, the consensus of both meta-analyses is that early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered the preferred management for patients with acute cholecystitis. Unfortunately, these reviews did not evaluate outcomes in the elder.

Even with these evidence-based recommendations, elderly patients have been shown to be more likely to be managed differently than younger patients. Previous studies have documented that up to 30 % of elderly patients do not have any surgical intervention for acute gallstone disease during the index hospitalization [66, 67]. This was initially perceived to be due to increased comorbidities or those presenting with acute complicated disease [5, 67]. Recently, in a single institution review, Bergman and colleagues showed that this may not be the reason [6]. They concluded that increasing age was independently associated with a lower likelihood of surgical intervention after adjusting for severity of biliary disease as well as preexisting medical comorbidities. This finding should give surgeons pause as prolonged delay in cholecystectomy increases the subsequent need for emergent surgical intervention [66, 68] with mortality rates as high as 6–15 % [49]. This contrasts with appropriately selected elderly patients that have electively scheduled cholecystectomy and outcomes that are similar to younger patients [13]. Thus, the patient’s age alone should not exclude early cholecystectomy if there are no or minimal comorbidities.

Some elderly patients with acute cholecystitis will present with severe sepsis and septic shock or have comorbidities that preclude consideration of early cholecystectomy. These patients need to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for supportive care in addition to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Obtaining source control in these patients obviously presents a clinical challenge. Two less invasive procedures, percutaneous cholecystostomy (PC) and ERCP, should be considered in these patients once underlying physiologic derangements have been corrected.

PC can either be done with the aid of either ultrasound or CT guidance. The use of ultrasound allows for the procedure to be performed at the bedside which avoids the need for transportation of critically ill patients to the CT scanner. After initial aspiration, a pigtail drainage catheter can be left in place for drainage. Cultures of the bile should be sent to tailor empiric antibiotic therapy, particularly if the elderly patient has come from a nursing facility or has received recent antibiotic exposure as this is associated with a higher incidence of resistant organisms. PC has excellent efficacy and results in the resolution of sepsis in up to 87 % of critically ill patients, with acceptable 30-day mortality rates [69]. This temporizing measure can allow optimization of the patient’s organ failure. The drainage catheter should be left in place for 6 weeks to allow for establishment of a fibrous tract prior to removal. In certain patients that are a prohibitive surgical risk due to their underlying medical problems, conservative management with PC cholangiography. All stones can be extracted prior to catheter removal [55, 70].

ERCP with selective cannulation of the cystic duct and stent placement is another treatment modality that may be particularly useful in those critically ill patients that are unable to undergo PC particularly in the setting of coagulopathy or uncontrolled ascites [71]. In experienced hands, this procedure is technically successful in over 90 % of cases with a reported clinical efficacy of 80–90 % [71].

PC should only be used as a treatment modality in those patients that are too critically ill or medically a prohibitive risk for general anesthesia. The procedure is associated with increased hospital lengths of stay and up to a 25 % rate of readmission for biliary related complications. A detailed Cochrane review comparing PC versus cholecystectomy as treatment for severe acute cholecystitis found no evidence to support the use of PC over surgical intervention [72]. A recent large retrospective single institution review reached similar conclusions even when accounting for patients that underwent conversion to open cholecystectomy [52]. Those patients that were treated surgically had shorter lengths of stay, as well as a lower complication rate and number of readmissions compared with those that underwent PC as treatment for acute cholecystitis. Only those patients that presented with comorbidities and medical risk for surgery as defined by the Charlson comorbidity index appeared to benefit from PC over surgical intervention for acute cholecystitis [52].

Chronic Calculous Cholecystitis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Biliary colic (symptomatic calculous disease) is the most common complication from gallstones. This scenario is typical in the elderly due to the alterations in pain perception and immune response to inflammation that have been described (see section “Diagnostic investigation”). The patient often will present with symptoms similar to those of acute cholecystitis without systemic signs of inflammation. Typically, the pain is located in the epigastrium/right upper quadrant and is dull and of less intensity compared to the pain which occurs with acute cholecystitis. Patients will be afebrile with normal laboratory studies. The metabolic panel should also be checked, particularly in the elderly patient as they often are on medications that can cause fluid and electrolyte derangement. Ultrasound examination should be obtained to confirm the presence of stones. Occasionally, the “double-arc” sign which is pathognomonic for a contracted gallbladder with calculi will be seen on ultrasonography [31]. Rarely, chronic cholecystitis may be associated with mural calcification of the gallbladder. This may involve a portion of the wall or the entire gallbladder otherwise known as a “porcelain” gallbladder (Fig. 12.10). The significance of this finding has been controversial due to the potential association with an underlying carcinoma particularly in older patients [73–75]. This finding on ultrasound should lead one to consider additional imaging such as CT or MRI [76].

Fig. 12.10

CAT scan of the abdomen showing complete calcification of the gallbladder wall (arrow) consistent with a “porcelain” gallbladder

Treatment of Chronic Calculous Cholecystitis

The initial treatment for biliary colic should be directed at relieving pain with the judicious use of narcotics. Intravenous fluids should be begun for dehydration. The patient should be seen by an anesthesiologist to determine the patient’s ASA score. Reasonable risk patients should be scheduled for elective cholecystectomy as soon as convenient since the recurrence rate for a subsequent episode of biliary colic or acute cholecystitis is 40 % over the next 2 years [77]. Delaying surgery because of age and waiting for an episode of recurrence of disease in the elderly is hazardous as they often present in a delayed fashion and with a higher incidence of complicated calculous disease that may require urgent/emergent cholecystectomy that is associated higher morbidity and mortality [6, 25, 49, 77].

Though the incidence of porcelain gallbladder remains low (0.2 %), there is a small risk for malignancy, particularly in those over 50 years of age (incidence of 0.08 %/year of symptoms) [77]. The management of the porcelain gallbladder has undergone considerable change over the past several decades. Early reports suggested a high association between a calcified gallbladder and carcinoma (up to 60 %) [78] which led to the recommendation for cholecystectomy once the diagnosis was made. Recently, several large clinical series have questioned the significance of the calcification of the gallbladder wall after finding a much lower incidence of malignancy (0–5 %) [74, 75, 78]. The reasons for this dramatic shift are felt to be due to the recent advances and increased usage of abdominal CT imaging which has allowed earlier diagnosis compared to earlier studies which relied on abdominal radiographs for the diagnosis [78].

The overwhelming majority of older patients diagnosed with a porcelain gallbladder also have symptomatic disease which would make them surgical candidates unless their operative risk was found to be prohibitive [74, 75, 78]. The asymptomatic patient with an incidental finding of a porcelain gallbladder represents a clinical impasse on whether to proceed with cholecystectomy or nonoperative management. The risk of surgical intervention, particularly in the patient with comorbidities, should be balanced against the low potential risk of gallbladder carcinoma and discussed with the patient in order to establish a course of action. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been found to be technically feasible in patients with a porcelain gallbladder and should be the initial procedure of choice. If carcinoma is confirmed once the gallbladder is resected, the procedure should be converted to an open resection of the liver bed and lymphadenectomy [78, 79].

Choledocholithiasis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The majority of choledocholithiasis originate from the gallbladder and are associated with a myriad of clinical symptoms. The incidence of symptomatic common bile duct stones is higher in the elderly population (range 15–20 %) compared to younger patients [49]. Up to a third of common duct calculi will spontaneously pass into the duodenum [80], while large stones may lead to common duct obstruction resulting in either gallstone pancreatitis or cholangitis.

Right upper quadrant pains with abnormal liver function tests are present in over 75 % of patients [81]. The laboratory studies usually reveal a cholestatic (elevated serum bilirubin) pattern and transaminases typically higher than 500 IU/L along with elevation of alkaline phosphatase or serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (90 % of cases) [82]. Leukocytosis may also be present in the acute phase, and coagulation parameters should also be evaluated. It should be noted that approximately 10 % of patients will be asymptomatic when the diagnosis is made incidentally on imaging studies obtained for a reason other than biliary symptoms [81, 83]. In the elderly, malaise, altered mental status, or acute deconditioning may be the only presenting symptoms [56].

As noted above, the initial imaging study to evaluate for common bile duct calculi is abdominal ultrasonography. If the ultrasound is normal but clinical and laboratory testings are consistent with choledocholithiasis, then MRCP should be considered as this has higher sensitivity than sonography. ERCP should generally be reserved for therapeutic purposes due to its invasive risks and technical complications.

Treatment of Choledocholithiasis

Once the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis is made, there are a variety of treatment options available, and these should be tailored based upon local expertise and resource availability. Initial treatment should be directed at alleviating pain, fluid resuscitation, and correction of any electrolyte or coagulation disorders that may be present. Complete removal of common duct calculi should be the objective regardless of the intervention chosen because up to 50 % of patients will have recurrence of symptoms if left untreated and 25 % of these recurrent cases will result in potentially serious complications (i.e., biliary pancreatitis or cholangitis) [82].

Endoscopic therapy with ERCP or percutaneous intervention (PTC) are both acceptable methods of ductal clearance according to the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SAGES) and British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines [48, 84] and should be chosen based upon local availability and expertise. As elderly patients are often on anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications, these should be withheld in anticipation of therapeutic intervention. Antibiotics should be given periprocedurally and should again be directed primarily against the Enterobacteriaceae family. ERCP with balloon dilation of the sphincter has an excellent clinical success rate and appears to be safe even in the elderly population with known comorbidities [49, 85].

Once the calculi have been removed from the common bile duct, elderly patients should be offered cholecystectomy if they are acceptable surgical candidates because of the potential for recurrent choledocholithiasis or acute cholecystitis. In a 2-year prospective study, Lee et al. found that age and the presence of comorbid conditions were risk factors for recurrent choledocholithiasis [86]. Additionally, these patients were felt to be at higher surgical risk at the time of the second episode than if they had initially had an early cholecystectomy. Similar findings were seen in a large systematic review done by the Cochrane group which found a decreased recurrence rate and increased survival advantage even in patients deemed “high risk” for early cholecystectomy as opposed to a nonoperative approach [87].

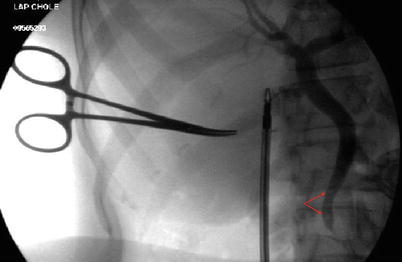

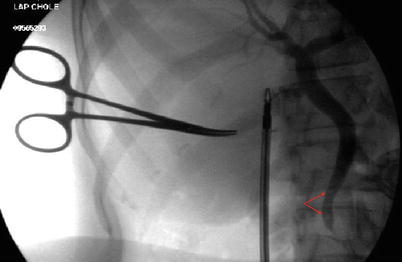

The timing of cholecystectomy after ERCP and sphincterotomy has also been investigated. In a prospective, randomized trial comparing early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (within 72 h) versus delayed cholecystectomy (6–8 weeks after ERCP), there were no differences in operative time or rate of conversion to open procedures, while 36 % of patients in the delayed group developed recurrent biliary symptoms [88]. The authors concluded that early cholecystectomy prevented future symptoms related to common duct stones without an increase in morbidity in those undergoing early operation. Patients that undergo ERCP with sphincterotomy and ductal clearance are still at risk for residual choledocholithiasis. Clinical studies assessing this risk have found it to be as high as 13 % [89, 90]. Therefore, the authors recommend routine use of intraoperative cholangiography in patients that had a preoperative ERCP with ductal clearance to reduce the chance of a retained common duct stone going undetected (Fig. 12.11). For those surgeons with advanced laparoscopic skills and institutions that have the instrumentation and imaging capability, single-stage procedures to treat choledocholithiasis (laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram followed by laparoscopic common bile duct exploration) have gained popularity. This leads to decreased hospital lengths of stay and total charges without an increase in associated morbidity or mortality [91–93]. This management strategy has also been validated in elderly and high-risk patients [94]. The benefits of one-stage treatment of choledocholithiasis have only been observed in uncomplicated cases (i.e., no cirrhosis, cholangitis, or biliary sepsis) [91] and with experienced laparoscopic surgeons [95].

Fig. 12.11

An intraoperative cholangiogram demonstrating two filling defects consistent with common bile duct stones (arrows)

Cholangitis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Cholangitis can follow a wide spectrum of disease in the elderly patient, from a mild infection to fulminant septic shock with multiple organ dysfunction. Early recognition of which form of disease is present is imperative to achieve good clinical outcomes. Obstructive choledocholithiasis is the most common etiology of cholangitis but may also occur in the presence of benign or malignant biliary strictures. Stasis of bile leads to bacterial overgrowth from the duodenum with Escherichia coli being the most common offending organism followed by other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Increased pressure in the intrahepatic bile radicles leads to translocation of bacteria into the hepatic veins and systemic bloodstream with resultant toxemia [82]. The classic clinical picture of Charcot’s triad (fever, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice) is present in 70 % of patients [82]. The addition of altered mental status changes and hypotension to Charcot’s triad are known as Reynold’s pentad and are indicative suppurative cholangitis. In addition to clinical exam findings, laboratory studies often reveal leukocytosis with elevated liver transaminases and cholestasis. Thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, and elevation of creatinine are diagnostic of more severe cholangitis [96]. Coagulation studies should also be assessed in preparation for ductal decompression as biliary obstruction with superimposed sepsis can lead to DIC. Diagnostic imaging is frequently done with ultrasonography that typically reveals dilation of the biliary ducts.

Treatment of Cholangitis

Initial therapy should be to establish intravenous access and begin fluid resuscitation followed by early administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Appropriate initial antibiotics include third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones combined with metronidazole, or beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations (i.e., piperacillin/tazobactam) [57]. Blood cultures should be collected but should not delay initiation of antibiotic therapy. Since most patients present with mild to moderate cholangitis (nonsuppurative), this will lead to clinical improvement within the next 24 h [48]. Even with initial improvement, elderly patients should be closely monitored for decompensation since age (>50 years) has been shown to be a predictor of poor outcomes [97]. Once sepsis has resolved, the duct is decompressed, and the patient is medically optimized, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be offered to the patient.

Patients that present with florid sepsis and organ dysfunction should be aggressively resuscitated in the intensive care unit with the aid of invasive monitoring. Hemodynamic support with vasopressors may be required in cases of septic shock, and optimization of physiologic parameters should be undertaken to allow for source control through biliary decompression with the least invasive means available. Endoscopic decompression with ERCP has become the initial procedure of choice for most patients, including the elderly [82]. The aim of the procedure is to relieve biliary pressure through minimal manipulation to prevent exacerbation of endotoxemia. Sphincterotomy aids with extraction of the calculi, and then biliary stent placement maintains decompression of the common bile duct. Should ERCP be technically difficult and unsuccessful, PTC is the next option. Even with successful decompression, there is still a mortality rate of 5–10 % [98]. In situations where ERCP/PTC is unsuccessful or unavailable, drainage can be accomplished surgically with open common bile duct exploration and T-tube placement. The mortality for this intervention is much higher than the preferred less invasive techniques (16–40 %) [81]. After successful biliary decompression and stabilization of the patient, antibiotic therapy should be continued for 14 days and the patient evaluated for cholecystectomy once medically optimized.

Biliary Pancreatitis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

A common bile duct stone will frequently impact at the ampulla and obstruct both the bile duct and the pancreatic duct. This results in stasis in both ducts with intraductal activation of enzymes and pancreatic glandular damage which results in a generalized inflammatory response that leads to subsequent symptoms. Risk factors for the development of gallstone pancreatitis include advanced age (>60) and female gender [99]. Most cases of biliary pancreatitis are moderate and will resolve with appropriate supportive care. However, more severe episodes of pancreatic inflammation can lead to sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction with mortality rates that exceed 20 % [100] and require a multidisciplinary approach including critical care support.

Symptoms of gallstone pancreatitis include sharp epigastric pain with radiation to the back that can be confused with acute aortic dissection or myocardial ischemia in the elderly. Nausea and vomiting are common. Signs of systemic inflammation response syndrome (SIRS) such as tachycardia and fever may also be present. In severe acute pancreatitis, patients can also have hypotension and altered mental status. Helpful laboratory investigations include CBC, serum chemistry with a serum calcium level, liver function tests, and serum amylase and lipase. Leukocytosis is often secondary to inflammatory response, and the hematocrit is often elevated from hemoconcentration as a result of third space fluid sequestration. Serum chemistry can also depict signs of impaired tissue perfusion if the serum bicarbonate is low or renal parameters are indicative of acute renal impairment. In cases of biliary pancreatitis, transaminases may be higher than 500 IU/L in the acute phase with a moderate elevation of serum bilirubin. Typically, both the serum amylase and lipase will be elevated, but the hyperamylasemia resolves earlier in the time course of pancreatitis than does the lipase.

Ultrasound examination should be the first imaging study obtained. This test can be done in unstable patients at the patient’s bedside. The identification of cholecystolithiasis or sludge in the gallbladder supports the diagnosis. Dilation of the biliary tree may also be noted on the exam. In patients that are clinically stable or that improve with resuscitation, CT imaging can be helpful in predicting the severity of pancreatitis [101]. In the critically ill patient with moderate to severe pancreatitis, the study should be performed without contrast to avoid exposing a hypovolemic elderly patient to a potentially nephrotoxic contrast material. Scans with IV contrast can be obtained at a later time when the patient is clinically stable to delineate areas of potential pancreatic necrosis.

Treatment of Biliary Pancreatitis

Initial therapy is directed at alleviating pain with judicious use of narcotics and nasogastric decompression for those patients presenting with symptoms of ileus. Generous fluid resuscitation should also be undertaken due to the amount of fluid sequestration that can occur in the retroperitoneum. There should be a low threshold to admit elderly patients to the ICU even in moderate cases due to their limited physiologic reserve. Many different scoring systems for determining the severity of pancreatitis have been developed [102–105], but the Ranson score has been shown to have the highest predictive accuracy [102]. A Ranson score of 3 or more is indicative of severe disease, and well-established evidence-based guidelines have been developed for treatment [106, 107]. There are three areas of current debate regarding the optimal therapy of gallstone pancreatitis. The first area of controversy in the treatment of severe pancreatitis is the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Recently several systematic reviews examining the utility of antibiotic prophylaxis in severe acute pancreatitis have been undertaken and have failed to demonstrate any benefit on mortality or the risk of developing infected pancreatic necrosis [108–110]. Due to problems with emerging bacterial resistance, the authors recommend against the routine use of antibiotic administration in sterile cases of severe pancreatitis. In instances when superimposed cholangitis is suspected with biliary pancreatitis, appropriate antibiotic therapy is warranted.

Another controversy involves the use of early (within 24–48 h) ERCP with sphincterotomy. In the past, literature supported early ERCP in patients with biliary pancreatitis that present with severe disease and moderate disease that did not exhibit clinical improvement or experience persistent pain [82]. A recent meta-analysis reexamined this topic utilizing seven prospective randomized trials (ERCP vs. conservative treatment) in patients that presented only with severe biliary pancreatitis without evidence of cholangitis [84]. The authors found that there was no significant benefit or difference in outcome in those patients that underwent early ERCP even when stratifying for disease severity. Therefore, early ductal decompression with ERCP should not be performed routinely as it provides no benefit to the patient.

The final area of discussion involves the timing of cholecystectomy after an episode of biliary pancreatitis. As mentioned in section “Choledocholithiasis”, the natural history of biliary pancreatitis is recurrence (up to a third of all patients) if the gallbladder is not removed [111]. Each recurrent episode places the patient at risk of life-threatening pancreatitis or cholangitis. Recently, the group from Harbor-UCLA investigated the feasibility of early cholecystectomy (within 48 h of admission) in patients presenting with moderate biliary pancreatitis (Ranson <3) and found no apparent increase in perioperative complications and a decreased hospital length of stay compared to those that had cholecystectomy delayed until after resolution of all abdominal pain or improved enzymatic parameters [112]. Other studies have found similar findings with the consensus being that laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed during the same admission for biliary pancreatitis in patients who are an acceptable surgical risk [111, 113, 114]. Despite the overwhelming evidence favoring cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis, a recent appraisal of this approach in elderly patients concluded that over 40 % of patients admitted with a diagnosis of gallstone pancreatitis in a large Medicare sample were not treated surgically and were associated with a high rate of recurrent acute pancreatitis (33 %) [115]. This study demonstrates the practice variations that exist in caring for elderly patients for this disease. For patients that are at a prohibitive surgical risk due to comorbid illnesses, ERCP with sphincterotomy does provide some protection against recurrent episodes of biliary pancreatitis and should be offered to patients that are considered to not be surgical candidates [114, 116].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree