First author, year

Study design

Study population

BI-RADS 3 assessment, n (%)

BI-RADS 3 patients, n (%)

Malignancy rate, n (%)

Kuhl [4], 2000

Prospective

High risk

45/363 (12.4)

44/192 (22.9)

1/26 (3.8)

Liberman [5], 2003

Retrospective

High risk

89/367 (24.2)

89/367 (24.2)

9/89 (10.1)

Hartman [6], 2004

Prospective

High risk

19/75 (25)

14/41 (34.1)

0/14 (0.0)

Kriege [7], 2004

Prospective

High risk

275/4169 (6.6)

NR/1909

3/275 (1.1)

Sadowski [8], 2005

Retrospective

BI-RADS 0 mammogram

NR

79/473 (16.7)

4/79 (5)

Kuhl [9], 2005

Prospective

High risk

167/1452 (11.5)

NR/529

NR/167

Eby [10], 2007

Retrospective

Mixed

160/809 (20)

160/678 (23.6)

1/160 (0.6)

Eby [11], 2009

Retrospective

Mixed

260/2569 (10.1)

236/1735 (13.6)

2/362 (0.6)

Weinstein [12], 2010

Prospective

Known contralateral cancer

106/969 (10.9)

106/969 (10.9)

1/143 (0.7)

Hauth [13], 2010

Retrospective

Mixed

44/698 (6.3)

44/698 (6.3)

1/56 (1.8)

Marshall [14], 2012

Retrospective

Mixed

132/NR

132/NR

2/132 (1.5)

Mahoney [15], 2012

Prospective

Known contralateral cancer

106/969 (10.9)

106/969 (10.9)

1/106 (0.9)

Lourenco [16], 2014

Retrospective

Mixed

348/4370 (8.0)

345/4370 (7.9)

5/348 (1.5)

Bahrs [17], 2014

Retrospective

Mixed

182/666 (27.3)

117/NR (17.6)

3/163 (1.8)

Spick [18], 2014

Retrospective

Not high risk, no history of breast cancer

108/1265 (8.5)

108/1265 (8.5)

1/108 (0.9)

Grimm [19], 2015

Retrospective

Mixed

282/4279 (6.6)

265/3131 (8.4)

12/280 (4.3)

Guillaume [20], 2016

Retrospective

Mixed

100/820 (12)

75/820 (9)

5/100 (5)

14.2 Literature Data and Evidence-Based Recommendations

As outlined in the previous section, the probably benign category (BI-RADS 3) in breast MRI is based on subjective decision without standardized and established imaging criteria. Most published studies that evaluated the frequency of a BI-RADS 3 assessment (recommendation for short-interval follow-up) on MRI report a rate between 6 and 12 % (Table 14.1). The range of different frequency rates can be partly explained by the study populations. Indications for MRI in these studies showed a wide range from high-risk screening, to problem solving and breast cancer staging. In 17 studies published between 2000 and 2016 and comprising 2608 lesions, 51 cancers were finally diagnosed (Table 14.1). Only 24 of these 51 (47 %) lesions were diagnosed by MRI follow-up. Eight (16 %) lesions were immediately upgraded after MRI-directed ultrasound examinations were performed [16, 19, 20]. Other malignancies were either detected as incidental findings after prophylactic mastectomy, interval cancers by palpation or mammography after 24 months. Finally, information regarding time to and method of diagnosis was missing in a number of cases. Considering a time frame of 24 months as adequate to differentiate new interval cancers from real lesion progression (change in follow-up), only the 24 malignant findings identified by MRI follow-up constitute the basis for doing MRI follow-up examinations. These correspond to a 0.9 % rate of false negative BI-RADS 3 lesions on MRI. It seems to be evident from these numbers, that MRI follow-up over 24 months in 6 months intervals may not be justified considering the low likelihood of malignancy, examination costs and patient compliance. Considering these data, we can recommend the following management of MRI BI-RADS 3 lesions:

First, immediate MR-directed ultrasound (also known as second look ultrasound or targeted ultrasound) of the MRI-detected lesion. Despite the fact that MR-directed ultrasound is not yet standard of care to check BI-RADS 3 findings, this approach is justified by the substantial number of second look ultrasound upgrades of MRI BI-RADS 3 lesions reported in the literature [16, 19, 20]. The value of MR-directed ultrasound is corroborated by a recent meta-analysis reporting a substantial pooled detection rate of MRI detected malignant findings of 79 % (95 % CI 71–87 %) [21]. The same publication reports a pooled detection rate of benign findings of 52 % (95 % CI 44–60 %), suggesting that a substantial rate of benign MRI BI-RADS 3 lesions may be identified and followed up by ultrasound [21].

Second, a single MRI follow-up in 6–12 months should be performed in case the BI-RADS 3 lesion is not visible on MRI-directed ultrasound. As the majority of breast cancer screening programs apply 2 year screening intervals, the additional value of a 2 year MRI follow-up does not seem to be justified considering the low likelihood of malignancy after the aforementioned workup.

These considerations do not take into account the possibility of a misclassification of BI-RADS 3 lesions that demonstrate the criteria for malignancy. Although data on this topic is sparse, such misclassification has been described in up to 80 % of false negative MRI BI-RADS 3 lesions that should have been called BI-RADS 4 [20].

BI-RADS 3 lesions that undergo follow-up MRI should be histopathologically verified if they show any change in size or morphology. If, however, the lesion demonstrates stability as compared to prior MRI examinations, a decrease in size, or shows a resolution at any point during follow-up, the lesion should be considered benign.

In the following sections, we will discuss imaging features for those breast lesion types that might appropriately be assigned BI-RADS 3 on MRI.

14.2.1 Diagnostic Criteria in BI-RADS 3 Lesions

In short, there is no definite set of features that define BI-RADS 3 lesions. While the literature reports on malignancy rates in different types (e.g. mass, non-mass, foci) of BI-RADS 3 lesions, no definite data on diagnostic criteria defining the BI-RADS 3 category are given. BI-RADS 3 category should be assigned to lesions presenting benign appearing imaging features in case the radiologist feels the need for further confirmation. Presence of suspicious morphologic features that are unlikely associated with a benign diagnosis should always be called BI-RADS 4 and not BI-RADS 3. Specific features will be discussed in the respective lesion type sections.

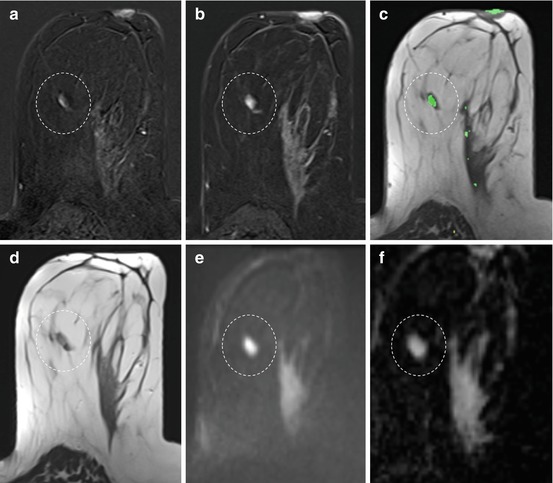

Care should be taken in transferring conventional mammography and ultrasound criteria directly to breast MRI. For instance, a newly diagnosed lesion showing only benign features does not necessarily need to be followed-up. This holds true especially for mass lesions with circumscribed margins and persistent or plateau enhancement curves. These findings are generally benign, especially when additional T2w and DWI features are considered (Fig. 14.1).

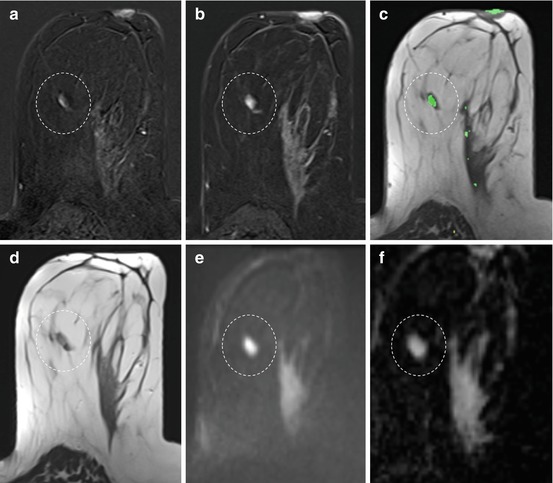

Fig. 14.1

Incidental lesion (dashed circle) on breast MRI of a 47-year-old woman performed for other reasons. Slow initial (a) and persistent late (b) enhancement, coded green on a parametric enhancement map (c). The lesion has a hyperintense and circumscribed T2w correlate (d) and shows high signal on the DWI image (e) and on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map (f). The quantitative ADC value was measured as 1.8 × 10−3 mm2/s. This finding fulfills all the criteria for a benign lesion and should rather be called BI-RADS 2 (benign finding) than BI-RADS 3 (probably benign finding). MR-directed ultrasound should be attempted in order to have documented the lesion for subsequent conventional screening rounds

Fibroadenomata, the most common benign lesions in the breast, usually show a circumscribed T2w correlate and high diffusivity on Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps [22]. The latter constitutes the juvenile myxoid or fluid-rich fibroadenoma type. These lesions can even show wash-out curve types, but the combination of high ADC and circumscribed margins excludes the only malignant lesion with high ADC values: invasive mucinous cancer. Fibroadenomata do mature, leading to a loss of water content and an increased hypovascularized stroma component over time. This loss of water may even cause low ADC values that are due to the low T2- signal rather than a real diffusion restriction. Although Schrading et al. have coined the term of fibroadenoma-like appearing cancers in high-risk patients [23], others have not confirmed this finding, and the authors’ conclusions are likely due to the reading method applied at that time (alternator views on printed films, visual assessment of signal intensity time curves). In our own clinical experience, we have never encountered a cancer lacking all three MRI hallmarks of malignancy: non-circumscribed or spiculated margins, plateau or wash-out curve types and restricted diffusivity. Moreover, basic consideration of tumor biology implies that dangerous, fast growing tumors may appear with circumscribed margins but their fast growth requires strong and typical hypervascularization and restricted diffusivity due to high cellularity. Again, the combination of circumscribed margins with low and persistent contrast medium uptake excludes any malignant diagnosis: invasive cancer is either not circumscribed or, if circumscribed, presents a highly proliferative lesion that will always show strong contrast uptake followed by wash-out or plateau curves.

The MRI BI-RADS lexicon is characterized by the lack of a clinical decision rule—a precise description of which diagnostic criteria constitute a specific diagnosis, e.g. BI-RADS 3. Although there are several classification systems in breast MRI, such as the Göttingen score [24] or the Jena Tree [25, 26], these systems do not provide rules to differentiate between benign and probably benign lesions. However, they assign levels of suspicion to specific feature combinations, allowing the user to assess whether a lesion is benign or whether the lesion is still benign but may need further follow-up. Still, the decision to differentiate between benign and probably benign lesions is largely a decision based on the clinical background, including patient age, individual breast cancer risk and prior imaging findings. That said, we can conclude the following: first, a lesion that is already known and does not show any imaging progression over time should generally not be assigned as BI-RADS 3 on MRI. Second, a newly diagnosed lesion should not be called BI-RADS 3 if unambiguous benign imaging features are present. This does also hold true for the high-risk screening situation. Here, many authors and colleagues prefer immediate biopsy of newly diagnosed lesions. However, considering the variety of MR imaging protocols and their sensitivity for contrast media, new or stronger enhancing lesions may show such characteristics either due to protocol differences or the cyclical physiologic enhancement in premenopausal women.

The clinical indication for the breast MRI should also be considered in evaluation of BIRADS 3 lesions. If a patient is referred to MRI, e.g., due to an asymmetric density in mammography without remarkable findings on ultrasound, the pretest probability for breast cancer is very low and the indication for the examination questionable. If an incidental lesion, that is a lesion not corresponding to the mammographic asymmetry, shows only benign characteristics, the likelihood of malignancy is negligible, and the lesion should be termed benign and not probably benign. The high sensitivity of MRI implies that many lesions detected by MRI may have been already present but were not seen on conventional imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree