Benign soft tissue tumors and reactive lesions are encountered frequently in Surgical Oncology practice. While benign, these lesions often cause local symptoms, and they may mimic or be confused with malignant lesions. In these cases, surgical management is required to establish the diagnosis. Table 29-1 shows a comprehensive list of benign and reactive entities. This chapter will focus on those most frequently encountered in clinical practice.

Comprehensive List of Benign Soft tissue Tumors and Reactive Lesions

| Benign Soft Tissue Tumors |

| Lipoma |

| Lipoblastoma |

| Angiolipoma |

| Angiomyolipoma |

| Angiomyelolipoma |

| Hibernoma |

| Elastofibroma |

| Granular Cell Tumor |

| Hemangioma |

| Lymphangioma |

| Leiomyoma |

| Schwannoma |

| Neurofibroma |

| Myxoma |

| Angiomyxoma |

| Reactive Lesions |

| Ganglion Cyst |

| Myositis Ossificans |

| Nodular Fasciitis |

| Sarcoma Masquerade |

Lipomas are the most common benign soft tissue tumor overall. They are fatty tumors that most often develop in the subcutaneous tissue of the trunk and proximal extremities; however, they can occur in deep sites including within muscle, and in the retroperitoneum and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Lipomas are usually solitary lesions but approximately 2% of patients may present with multiple lesions that may or may not exhibit a familial pattern. No environmental risk factors for solitary lipomas have been identified.

Benign lipomas are characterized by specific molecular aberrations including translocations of 12q13-15 or rearrangements involving 13q or 6p21-33.1 Histologically, they are composed of enlarged adipocytes arranged in a well-encapsulated, lobular mass with a thin fibrous capsule (Fig. 29-1).

Patients often present with a soft, mobile, palpable mass in the subcutaneous tissue and will often report very slow or no growth over time. Intramuscular lipomas present as more of a generalized swelling than a discreet mass given their deeper location. They are usually not well encapsulated but are more infiltrative into the surrounding muscle fibers. Lipomas are usually painless and asymptomatic. GI tract lipomas may also be diagnosed incidentally, but occasionally cause intussusception, obstruction, or GI bleeding.

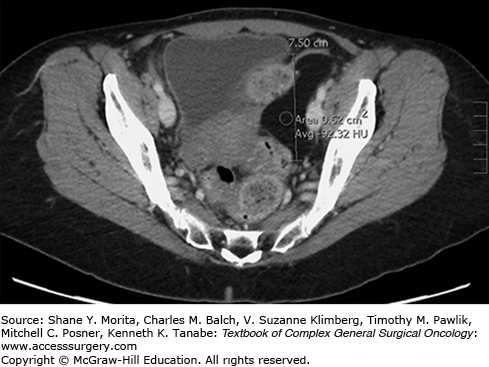

Small, subcutaneous lipomas are often apparent on physical examination and no imaging studies are required. Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful in assessing deep-seated lesions and intramuscular lesions. Regardless of location, most benign lipomas appear as homogenous, well-circumscribed, unilobular fatty masses. On CT, they have attenuation of −70 to −150 Hounsfield units (HU)2 (Fig. 29-2). GI tract lipomas share these same characteristics on cross-sectional imaging. They are soft and often appear compressible/mobile on fluoroscopy. Intramuscular lipomas may appear heterogenous due to intermingled muscle fibers and may have infiltrative borders.3

Surgical excision is performed primarily for cosmesis in the case of small subcutaneous lipomas, and is generally recommended for lesions larger than 5 cm. Deep-seated lesions such as those within muscle, in the retroperitoneum, and in the bowel wall should be removed to exclude possibility of well-differentiated liposarcoma (WDLS). Additionally, bowel wall lipomas have been reported to cause complications including GI bleeding and intussusception.4,5

Angiomyolipomas are soft tissue tumors arising almost exclusively in the kidney and liver. They present most often in adults and most often in females. As the name suggests, angiomyolipomas are composed of blood vessels, smooth muscle cells, and mature fat in variable proportions. Because of this histologic heterogeneity, percutaneous biopsy is often nondiagnostic, and appearance on imaging studies is highly variable. Of the histologic components, smooth muscle cells, which stain positive for HMB-45 and vimentin, are the only definitive diagnostic feature. While angiomyolipomas are generally benign, they can still cause life-threatening local complications such as spontaneous rupture, hemorrhage, caval thrombosis or occlusion, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC). Malignant transformation and recurrence/metastasis are exceedingly rare, but have rarely been reported.

Angiomyolipoma is the most common mesenchymal tumor of the kidney. The overall incidence of renal angiomyolipoma is 0.1% to 0.2%. Eighty percent of cases are sporadic and 20% occur in the setting of tuberous sclerosis (TS).6 There is a female predominance (4:1), and the mean age at diagnosis is 43 years. Renal angiomyolipoma is usually solitary but may be multiple in the setting of TS.

Hepatic angiomyolipomas are rare with only about 200 cases reported in the literature. They are similar to their renal counterpart in female preponderance and mean age at diagnosis (43 years).7 Hepatic lesions are usually solitary and small, but can grow to be very large. Unlike renal lesions, they are not associated with TS or other genetic syndromes.

The presence of fat within renal angiomyolipomas is the key, pathognomonic feature on imaging studies (ultrasound, CT, and MRI) and is considered diagnostic. Lipid-containing renal cell carcinoma, liposarcoma, and lipoma must be kept in mind, however. Percutaneous biopsy is recommended in rare cases of diagnostic uncertainty where biopsy results would affect further management.6

Hepatic angiomyolipomas, on the other hand, are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. This is in part due to the relative rarity of hepatic lesions, but also due to the fact that intralesional fat, the imaging feature that sets renal angiomyolipoma apart from other kidney tumors, is common in many different benign and malignant liver tumors. In recent series of hepatic angiomyolipoma, the correct diagnosis was made preoperatively in only 18% to 23% of patients.7,8 Hepatic angiomyolipomas are often very heterogenous-appearing lesions (Fig. 29-3) and are often confused with hepatocellular carcinoma.9 Angiomyolipoma should be suspected in patients with normal alpha-fetoprotein levels and no hepatitis or cirrhosis.

Renal angiomyolipomas <4 cm can be followed with surveillance imaging. Lesions >4 cm and growing lesions should be treated with surgical resection (nephron-sparing techniques if possible) or selective embolization as bleeding complications are more common above this size threshold.6 For hepatic lesions, wide excision is considered curative and is the recommended treatment for symptomatic or growing lesions. Selective embolization is an option to manage lesions complicated by hemorrhage or in patients not fit for surgery. Surgery is also recommended if a definitive diagnosis cannot be made preoperatively and malignancy cannot be ruled out.

Myelolipomas are benign soft tissue tumors that occur primarily in the adrenal gland. These tumors are composed of mature adipocytes and hematopoietic elements. The reported incidence in autopsy series is 0.1% to 0.4% with equal distribution in men and women.10 The mean age at diagnosis is about 50 years. They vary in size but can grow to be quite large. In a recent series of 16 patients undergoing adrenalectomy for myelolipoma at Washington University, the mean size was 9.6 cm (range 2.8 to 30 cm).11

Myelolipomas are most often diagnosed incidentally on imaging performed for other indications and they constitute about 7% of adrenal lesions. When present, symptoms are usually related to mass effect and can include pain, palpable mass or abdominal distention, and lower extremity swelling from caval compression. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage has also been reported.

Cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI is usually diagnostic for myelolipoma based on the pathognomonic finding of macroscopic fat within the lesion.12 Surgical resection is considered curative and is indicated for symptomatic lesions or those with atypical imaging features when the diagnosis cannot be established preoperatively. Laparoscopic resection is often feasible, even for lesions >7 cm in size, as they are usually well encapsulated and easily mobilized from surrounding structures.11 If there is any suspicion of adrenal cortical carcinoma, however, open resection is recommended.

Leiomyomas are benign soft tissue tumors arising from smooth muscle cells. They occur most often in the uterus but may also arise from the smooth muscle layers of the GI tract. GI leiomyomas were previously thought to be quite common, but since the discovery of the activating c-KIT mutation specific to GI stromal tumors (GISTs), it is now known that many lesions earlier thought to be leiomyomas were in fact GISTs. In a recent review of GI mesenchymal tumors treated at a single center, 50% were GISTs and 30% were leiomyomas.13

The esophagus is the most common site of GI leiomyoma and is the only site in the GI tract where leiomyomas remain more common than GISTs.14 Esophageal leiomyomas are most common in the mid-to-distal esophagus and arise from the circular smooth muscle layer. Esophageal leiomyomatosis is a rare, hamartomatous condition characterized by diffuse proliferation of the circular smooth muscle in the distal esophagus. It may be sporadic or hereditary and is associated with Alport’s Syndrome (nephropathy, hearing impairment, astigmatism, and myopia).15 Gastric leiomyomas are rare but occur most often in the cardia region. Leiomyomas of the small intestine, colon, and rectum are also exceedingly rare.

Leiomyomas are composed of uniform spindle cells with little or no atypia. They stain positively for desmin and smooth muscle actin. In the GI tract, they most commonly arise from the muscularis propria layer, but may also arise from the mucsularis mucosa layer.

Small leiomyomas of the esophagus and stomach are typically asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally on esophagogastroscopy or cross-sectional imaging. Large lesions may cause dysphagia. Leiomyomas of the small intestine and colon may present with obstruction or intussusception. Large lesions at any location in the GI tract may develop central ulceration and resultant GI bleeding.

On cross-sectional imaging, leiomyomas typically appear as smooth, well-encapsulated submucosal lesions. They are homogenous-appearing, low-attenuation lesions and do not exhibit invasion into adjacent structures. On endoscopy they appear as smooth, submucosal masses. They most often exhibit intraluminal growth. Esophageal leiomyomatosis often mimics achalasia on fluoroscopic examination.

Enucleation is the treatment of choice for esophageal leiomyomas. Large lesions may require thoracotomy for removal, but small tumors can often be enucleated thoracoscopically or laparoscopically depending on location in the esophagus. Esophagectomy is occasionally required for very large lesions or for multiple lesions in cases of esophageal leiomyomatosis. Postoperative complications include esophageal leak, reflux, and formation of pseudodiverticula. Gastric leiomyomas can similarly be removed by enucleation or wedge resection. Segmental bowel resection is recommended for symptomatic lesions in the small bowel or colon. The distinction between leiomyomas and GISTs is important because postoperative surveillance is not indicated for the former, but is important for the latter.

Hemangiomas are benign proliferations of blood vessels and can be classified by location in the body, age of patient at diagnosis (infantile/congenital), or by the type of blood vessel involved (e.g., capillary, cavernous, venous). Little is known about the molecular biology of hemangiomas. In infants and children, most are cutaneous lesions that appear as small, red lesions on the face or extremities that are generally asymptomatic. Most infantile hemangiomas involute spontaneously and do not require treatment. There is, however, evidence to suggest that infantile cutaneous hemangiomas are markers of liver hemangiomas.

Cavernous hemangiomas of the liver are the most common type encountered by the surgical oncologist. They represent the most common benign mesenchymal tumors of the liver. They are most often asymptomatic and are found incidentally on imaging studies. They are most often small (<4 cm) and solitary, but they may be multiple. Liver hemangiomas >5 cm in diameter are referred to as “giant hemangiomas.” The prevalence of liver hemangiomas is estimated to be 0.5% to 20%. They present most often in the age range of 30 to 50 years and are more common in women than men (3:1).

Natural history studies have confirmed that the majority of liver hemangiomas remain stable over time (approximately 85% to 90%).16 However, growth may occur, and has been associated with pregnancy and estrogen/progesterone therapy. In one study of 27 pregnant women with liver hemangiomas followed with surveillance imaging, 12 (44%) grew over time, and there was one spontaneous rupture.17 Large hemangiomas have been shown to decrease in size with cessation of hormonal therapy. Despite these observations, there is no established molecular mechanism for hormonal influence on growth. Estrogen and progesterone receptors frequently are not present on the vascular endothelial cells within hemangiomas.

When present, symptoms most often include abdominal pain and fullness. Chronic pain can result from pressure on Glisson’s capsule. Acute onset, sharp pain is more often seen with rupture. Giant hemangiomas can rarely cause high-output cardiac failure, hypothyroidism, and a consumptive coagulopathy known as Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome.

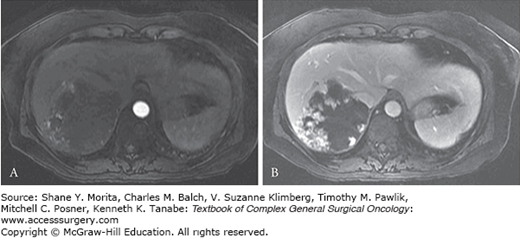

Hemangiomas can usually be reliably diagnosed with noninvasive imaging. Ultrasound, CT, and MRI are all utilized, but MRI has emerged as the best noninvasive test for the diagnosis of liver hemangiomas, with approximately 90% sensitivity and 95% specificity.18 Lesions are usually hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2. With administration of contrast, they exhibit a rapid, peripheral nodular enhancement on arterial phase images. On delayed phase, they demonstrate progressive central filling or centripetal enhancement (Fig. 29-4). This same pattern is also demonstrated on contrast-enhanced CT. Percutaneous needle biopsy is generally not recommended when hemangioma is high in the differential diagnosis.

Surgical resection is recommended for symptomatic hemangiomas of any size causing pain, compression of adjacent structures, coagulopathy, or hemorrhage, and in cases where malignancy cannot definitively be excluded. Management of asymptomatic giant hemangiomas is more controversial, but the risk of spontaneous rupture in these lesions is quite small, with only 34 published cases in the literature.19 These patients should be followed with surveillance imaging, as rapid growth can occur. Those with stable, asymptomatic lesions should be managed conservatively with continued surveillance. Peripherally located lesions are theoretically at a slightly higher risk of traumatic rupture than centrally located lesions, but no definitive association between location and risk of rupture has been shown. Individuals with large, peripheral/subcapsular hemangiomas involved in contact sports or occupational trauma may be considered for resection. In women with hemangiomas ≥4.0 cm, any hormonal therapy should be stopped. In women of childbearing age and in pregnant women, hemangiomas should be closely followed for enlargement, but prophylactic resection is not indicated. Small hemangiomas <2.0 cm can safely be followed.

Surgical resection by enucleation is often possible for hemangiomas, especially those that are peripherally located. There are no prospective studies comparing outcomes following enucleation versus formal anatomic resection of hemangiomas. Anatomic resection may be required for central lesions approximating major inflow or outflow structures. Rarely, liver transplantation may be required for unresectable symptomatic lesions. Patients presenting with spontaneous rupture have a high risk of surgical mortality (36%).20 Arterial embolization prior to surgery has been proposed as a means of reducing operative morbidity/mortality.21–23 Arterial embolization alone is indicated for patients not fit for surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree