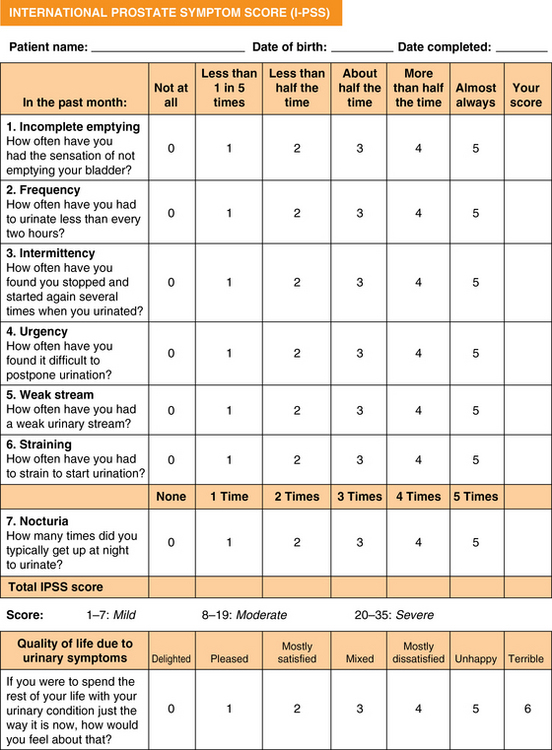

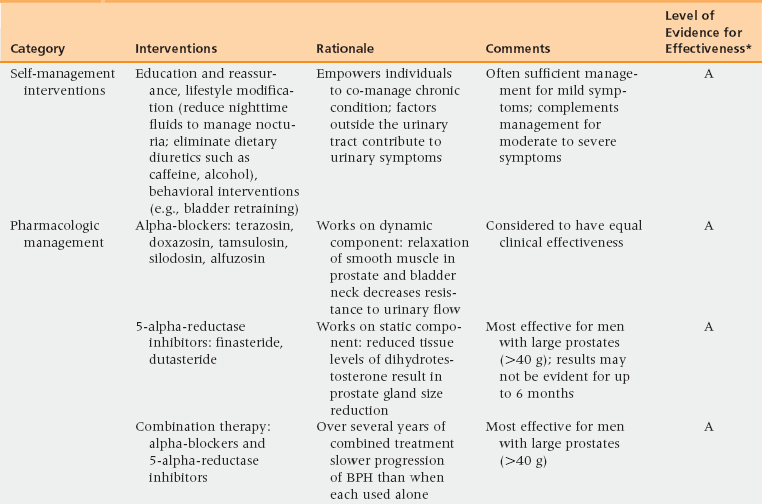

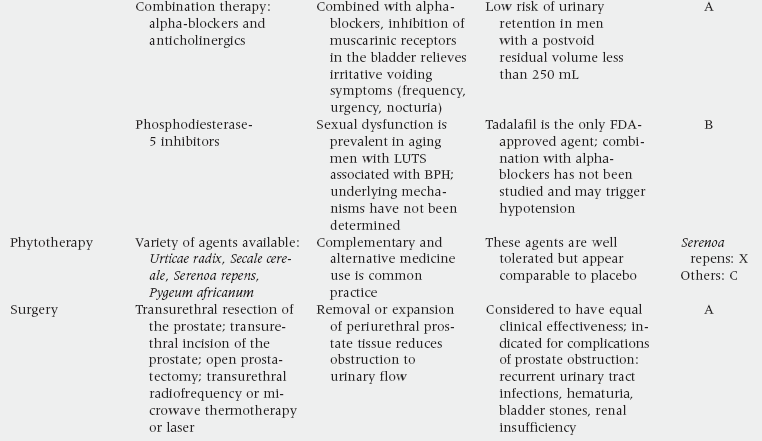

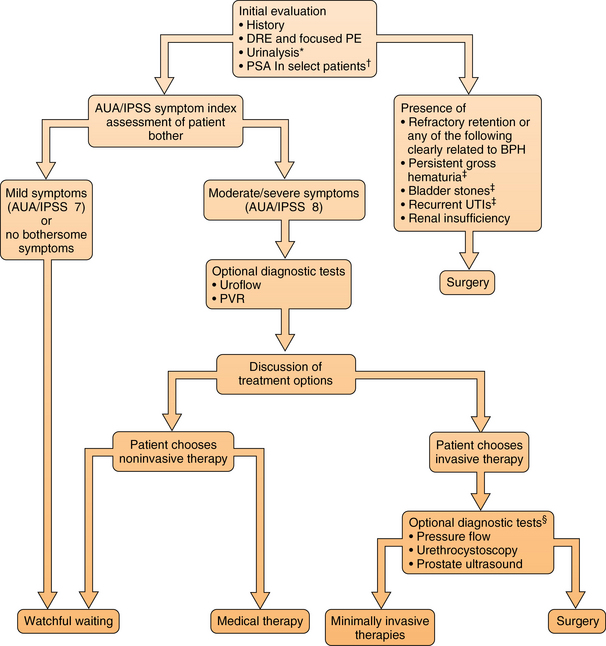

51 Risk Factors and Pathophysiology BPH: Differential Diagnosis and Assessment Lifestyle Interventions and Self-Management Combination Therapy: Alpha-Blockers and 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors Combination Therapy: Alpha-Blockers and Anticholinergic Medications Prostatitis: Differential Diagnosis and Assessment Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the clinical anatomy, physiology, and age-related changes of the prostate. • Describe common lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in an aging male. • Know how to diagnose benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). • Delineate the treatment options for BPH. • Understand the framework for the diagnosis and treatment of prostatitis. Voiding of urine is a synchronized action between the bladder and urethra. The bladder is innervated by parasympathetic nerves and their stimulation causes bladder muscle contraction leading to voiding of urine. Stimulation of sympathetic nerves that innervate the bladder neck and prostate causes closure of the bladder outlet. A voluntary sphincter in the bladder neck, supplied by the pudendal nerve and controlled by the higher cortical centers and diencephalons, enables conscious control of urine voiding. Multiple factors, including changes in the bladder, prostate, and/or urethra, can lead to voiding dysfunction in an aging male. Histologically, BPH is categorized as a hyperplastic process that results in enlargement of the prostate that may cause restriction in the flow of urine from the bladder. Subsequently obstruction induces bladder wall changes, such as thickening, increase in trabeculations, and irritability, that contribute to LUTS. Increased bladder sensitivity (detrusor overactivity [DO]) occurs even with small volumes of urine in the bladder. The bladder may gradually weaken and lose the ability to empty completely, leading to increased residual urine volume and, possibly, acute or chronic urinary retention. The International Continence Society has published standard terminology to define symptoms, signs, urodynamic observations, and conditions associated with lower urinary tract dysfunction.1 LUTS are divided into three groups: storage, voiding, and postmicturition symptoms. Storage (irritative) symptoms include increased daytime frequency (voiding too often during the day), nocturia (to wake at night one or more times to void), urgency (sudden urge to urinate that is difficult to defer), incontinence (complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine), and bladder sensation (defined by five categories: normal, increased, reduced, absent, and nonspecific). Voiding (obstructive) symptoms are experienced during the voiding phase and include a slow stream (perception of reduced urine flow), splitting or spraying (character of stream), intermittent stream (urine flow that starts and stops), hesitancy (difficulty in initiating micturition), straining (muscular effort used to initiate, maintain, or improve the urinary stream), and terminal dribble (prolonged final part of micturition, when flow has slowed to a trickle/dribble). Postmicturition symptoms are experienced immediately after micturition and include a feeling of incomplete emptying (sensation of not emptying the bladder completely after finishing urinating) and postmicturition dribble (involuntary loss of urine immediately after completion of urination, usually after leaving the toilet in men, or after rising from the toilet in women). The diagnosis of BPH in men is typically clinical, and one of exclusion. When a urinary symptom is noted, a standardized questionnaire, such as the IPSS, is used to quantify the severity of LUTS (Figure 51-1). The IPSS assesses seven symptoms during the past month. The questions address the following factors: feeling of incomplete bladder emptying, frequency, intermittency, urgency, weak stream, straining, and nocturia; each is rated on the scale on which 0 = none and 5 = almost always. The symptom categories are based on the summative score: 0 to 7 mild, 8 to 19 moderate, and 20 to 35 severe. Figure 51-1 The International Prostate Symptom Score is based on the answers to seven questions related to lower urinary tract symptoms. Each symptom is scored 0 to 5 for a possible total score between 0 and 35. Question 8 refers to the patient’s perceived quality of life but is not included in the scoring of the IPSS. The IPSS is similar to the American Urological Association’s Symptom Index. (Barry M, Fowler FJ, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association Symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 1992;148:1549-57.) Other possible contributors are queried, such as endocrine (e.g., poorly controlled diabetes), neurologic (e.g., neurogenic bladder), symptoms of urinary tract infection, and previous urologic conditions (e.g., urethral stricture, bladder neck contracture, interstitial cystitis). Although nonspecific for BPH, DRE is performed to rule out other conditions. The prostate size, tenderness, and presence of nodules are noted. Because hyperplasia may only involve the transitional zone, the DRE can be unremarkable or it may reveal an enlarged, smooth, rubbery, symmetrical gland. Lower abdominal/suprapubic palpation may identify a distended bladder. Urinalysis is routinely performed to evaluate for urinary tract infection, hematuria, and glycosuria; BPH is associated with an unremarkable urinalysis. The initiation of BPH therapy depends on the patient and is driven by the effect of the symptoms on the patient’s quality of life (Table 51-1 and Figure 51-2). All patients should be educated regarding lifestyle modification. Men with mild to moderate symptoms may be satisfied with lifestyle modification only. Both medical and surgical treatments are also available, with medication the usual first approach. Indications for surgical treatment include patient preference, dissatisfaction with medication, and refractory urinary retention. Complications from prostatic obstruction, including renal dysfunction, bladder stones, recurrent urinary tract infections, and hematuria are also managed surgically. The selection of surgical approach is dependent on patient anatomy and the surgeon’s experience as well as the potential benefits and risks for complications. TABLE 51-1 Management Options for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia BPH, Benign prostatic hyperplasia; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Figure 51-2 Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of BPH. AUA, American Urological Association; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; DRE, digital rectal exam; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; PE, physical exam; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PVR, postvoid residual urine; UTI, urinary tract infection. BPH is a chronic condition with symptoms that impact men’s quality of life. As with other chronic conditions, patients benefit from self-management interventions (SMIs) that empower the individual’s involvement and control of treatment. SMI helps patients learn what to do and develops their belief in their own ability to use knowledge and skills toward achieving realistic, desired outcomes. SMI has been shown to be effective in men with BPH LUTS as an alternative to initial pharmacologic management and as adjuvant therapy for men who are using alpha-blockers.2,3 Three major categories for LUTS SMI are (1) education and reassurance, (2) lifestyle modification, and (3) behavioral interventions.

Benign prostate disease

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Overview of anatomy and physiology including age-related changes

Clinical manifestations

BPH: Differential diagnosis and assessment

BPH: Management

*In patients with clinically significant prostatic bleeding, a course of a 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor may be used. If bleeding persists, tissue ablative surgery is indicated.

†Patients with at least a 10-year life expectancy for whom knowledge of the presence of prostate cancer would change management or patients for whom the PSA measurement may change the management of voiding symptoms.

‡After exhausting other therapeutic options as discussed in detail in the text.

§Some diagnostic tests are used in predicting response to therapy. Pressure-flow studies are most useful in men prior to surgery. (Redrawn from American Urological Association. © 2003 American Urological Association Education and Research, Inc.)

Lifestyle interventions and self-management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Benign prostate disease