Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy afflicting mankind. Sometimes referred to as a rodent ulcer, the tumor was recognized by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans in ancient times.1 In 1827, Arthur Jacob provided the first detailed clinical definition of BCC in a publication titled “Observations respecting an ulcer of peculiar character, which attacks the eye-lids and other parts of the face.”2

Basal cell carcinoma usually occurs in fair-skinned individuals with sun-damaged skin.3 It is three to four times more common than squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and its incidence varies dramatically across various regions of the world reflecting the ethnic mix, ambient ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, and sun behavior habits of the population.3 The highest rates of BCC occur in Australia where national studies have documented a rate of 884/100,000 person-years, with an even higher incidence rate in some regions.3,4 The lowest recorded rates of BCC are in parts of Africa, with rates of less than 1/100,000 person-years.3 Globally, the incidence of BCC is increasing and European studies indicate that rates of BCC in Europe have been increasing on average by 5.5% each year.3 This increase in incidence is particularly dramatic in older age groups, with the greatest increase occurring in people aged 60 years and older.5 Less than 1% of all BCCs occur in individuals less than 25 years of age and there is a gender disparity in incidence with males affected more commonly than females; however, the extent of the disparity varies depending on the subtype of BCC.6 Anatomically, BCCs are most commonly identified on the face, followed by the neck, shoulders, back, and upper limbs.7 The relative density of BCCs is low in body sites that receive little sun exposure, namely the buttocks, thighs, feet, and in women, the scalp.7

BCCs rarely metastasize, with only approximately 300 to 400 cases reported in the literature.8,9 The rate of metastasis is reported to be between 0.0028% and 0.55%, but it is likely to be closer to 0.0028%, as noted in a survey of Australian dermatologists.8,9 A number of tumor characteristics have been identified that are associated with an increased risk of developing metastases. These include male gender, lesions on the head and neck, lesion size (with larger and locally invasive (T4) lesions being at higher risk), and recurrence after surgery or radiotherapy.9,10 The most common site for metastatic spread is to regional lymph nodes; however, hematogenous spread occurs very occasionally, with involvement of lung, bone, and to a lesser extent other internal organs.10

As well as skin phototype, risk factors for the development of BCC include cumulative and sun-burning UV radiation, immunosuppression, genetic disorders, HIV/AIDS, ionizing radiation, photosensitizing medications, and arsenic and occupational factors.11

A high degree of exposure to UV radiation greatly increases the risk of developing BCCs. Both UVA (320 to 400nm) and UVB (290 to 320 nm) cause genetic damage in the skin, and both can potently suppress cutaneous immune responses.7,12 UVA radiation mainly produces reactive oxygen species that react with tissues to cause indirect DNA damage,11 while UVB radiation primarily induces covalent bond formation between adjacent pyrimidines in DNA. The resulting photoproducts such as cyclodipyrimidine dimers (TT) and pyrimidine-pyrimidine dimers are mutagenic.11,13 Studies of tanning device use show that it is associated with an odds ratio of 1.5 for developing BCC when compared to the general population.14 The relative risk of developing a BCC in the context of having a skin phototype that is able to tan only moderately compared to deeply is 1.9.7 Individuals with phototypes that mount a minimal response to sunlight exposure by producing only a light tan or in more extreme cases no tan at all have relative risks for the development of BCC of 3.2 and 3.7, respectively, when compared to individuals who are able to tan deeply.7 Individuals who have had significant nonoccupational sun exposure and those who have experienced a sunburn at any age suffer relative risks of 1.38 and 1.40 for the development of BCC when compared to the general population.7

Chronic immunosuppression in the context of organ transplantation is also associated with an increased risk of BCC development.11 Numerous studies have documented that the incidence of BCC in transplant recipients is 5 to 16 times greater than in the general population.11,15–16 BCC is less common than SCC in transplant recipients, with the BCC/SCC ratio approximately 1:4, but BCCs typically occur earlier after transplantation than SCCs.11,17,16 Although not as dramatic, patients treated with glucocorticoids for one month or longer in nonorgan transplant situations have also been shown to have a modest elevation in BCC risk, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.49.18

In nontransplant immunosuppressive conditions such as HIV and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), there is also an increased risk of developing BCC. In a study of HIV-infected hemophiliacs, BCCs were found to occur 11.4 times more often than in the general population.19 HIV patients have also been noted to suffer from more aggressive forms of BCC, including infiltrating and morpheaform lesions and metastatic disease.19 Similarly, there is significant evidence showing that these cancers also behave aggressively in other immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplantation recipients and those with chronic hematological malignancy such as chronic lymphocytic leukaemia.20 In fact, tumors in the immunosuppressed typically exhibit subclinical extension and demonstrate features consistent with poorer prognosis.20,21 Oncogenic HPV subtypes have been isolated in up to 60% of BCCs arising in immunosuppressed individuals compared with 36% of tumors from immunocompetent individuals.11 BCCs also have higher recurrence rates (even after Mohs) in patients with haematological malignancies. Recurrence rates in excess of 8% have been reported for patients with CLL/NHL treated with Mohs.22 The use of wider excision margins, margin controlled excision (Mohs), and lower thresholds for adjuvent radiotherapy should be strongly considered in this cohort of patients.

Ionizing radiation has been utilized in the treatment of malignancies, inflammatory dermatoses, and ankylosing spondylitis, as well as other conditions,23 and is also an established risk factor for developing BCC.24 Individuals exposed to 35 Gy or more are almost 40 times more likely to develop BCC than those exposed to background levels.24 This increased risk of developing BCC is linearly related to the exposure dose and increases by 1.09 times per Gy.24 Exposure to radiotherapy in the context of cancer treatment has been shown to produce a two-fold increase in the risk of developing a BCC, whilst radiotherapy for the treatment of acne increases this risk by ~17 fold.23

Gorlin’s syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum are two rare genetic syndromes that are associated with an increased risk of developing BCC. Gorlin’s syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome) is an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome caused by a germline mutation in the PTCH gene. Patients with Gorlin’s syndrome typically develop multiple BCCs, often beginning in early childhood. Other phenotypic manifestations of the syndrome include epidermal cysts of the skin, odontogenic keratocysts of the jaws, palmar and plantar pits, calcified dural folds, various stigmata of maldevelopment, ovarian fibromas, medulloblastomas, and other tumors and hamartomas.25 Xeroderma pigmentosum is an autosomal recessive disorder of nucleotide excision repair that is characterized by a high incidence of SCC and melanoma and to a lesser extent BCC.25

The cell of origin for BCC remains unknown and controversial. For many years, it was generally considered that because BCCs are composed of cells resembling those of the basal layer of the epidermis, they arose from these cells. More recent theories, whilst still not definitively proven, have postulated that BCC likely arise from interfollicular epidermal stem cells or isthmus/infundibulum cells or both.26,61 There is now less evidence to support the previously leading theory that BCCs primarily arose from hair follicle bulge stem cells. Exposure to UV light is the primary etiologic agent in BCC development. Mutations in tumor suppressor gene p53 and dysregulation of the Hedgehog pathway lead to the formation of BCC.25 UV radiation is known to damage DNA and induce mutations within p53. Of all p53 mutations, 65% exhibit a characteristic signature of UV-induced damage, while 56% of all BCCs demonstrate p53 mutations.25 Dysregulation of the Hedgehog pathway due to either deletion or inhibition of PTCH, activation of smoothened, or overexpression of Gli1 or GLi2 also results in BCC.26 PTCH mutations occur in 30% to 40% of sporadic BCCs.25 Autosomal dominant inheritance of a PTCH1 germline mutation is known to be responsible for Gorlin’s syndrome.25,26

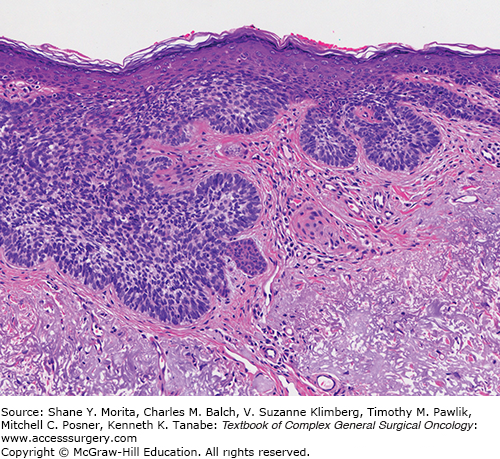

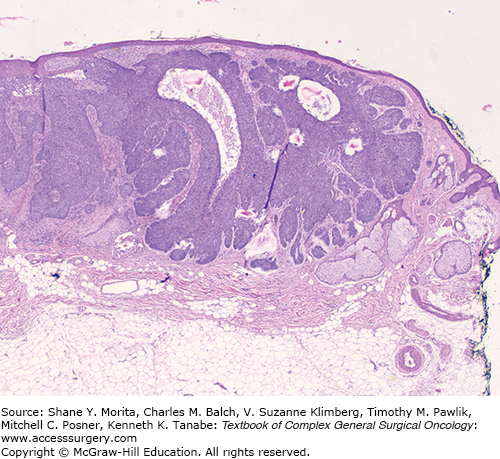

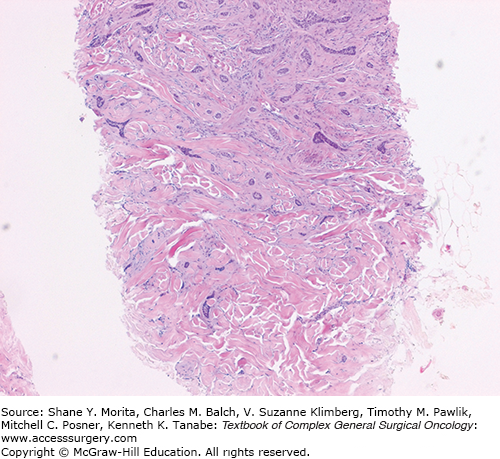

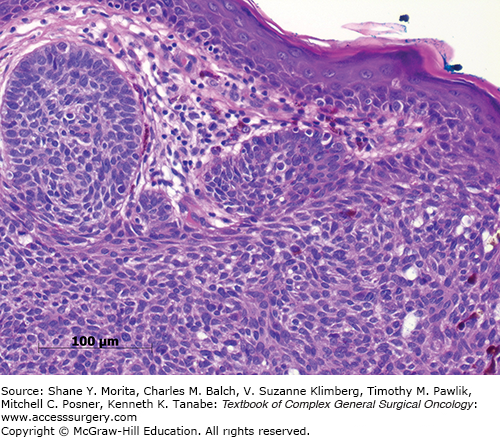

Basal cell carcinomas are primarily classified into a number of subtypes based on histologic growth patterns.27 The main histologic subtypes include superficial (Fig. 22-1), nodular (Fig. 22-2), infiltrating, morphoeic (Fig. 22-3), micronodular, and basosquamous. Nodular and superficial lesions are the most common and account for approximately 48% and 26% of all BCCs, respectively.6 Superficial BCCs present as erythematous patches or plaques that are often well demarcated and exhibit a slightly pearly appearance, in many cases. Nodular BCCs present as nodules or papules with a pearly appearance often associated with telangiectasia (Fig. 22-4). Histologically, these lesions are characterized by ovoid lobules (“nests”) of tumor cells with peripheral palisading. Stromal mucin accumulation is typically apparent both within BCCs and focally surrounding some nests, where it is often associated with retraction artefact.28 Pigmented BCCs account for 6% of all BCCs and are characterized by the presence of melanin pigment either within the tumor cells themselves or within macrophages in the adjacent stroma (Fig. 22-5).29

Superficial and nodular BCCs are generally considered to be subtypes with a low risk of recurrence whereas micronodular, infiltrating, morpheic, and basosquamous subtypes are considered high risk. Micronodular BCCs contain small islands of neoplastic tissue less than 0.15 mm in diameter, often extending deeply into the dermis or subcutis with little associated stromal desmoplasia and as a consequence often extend well beyond their clinically apparent peripheral edge.30 Infiltrating BCCs are characterized by irregular and widespread distribution of tumor cell groups, with lesions demonstrating significant locally invasive behavior.28 Morphoeic BCCs are relatively uncommon, comprising approximately 2% of all BCCs. They are characterized by dense stromal fibrosis with tumor compressed into narrow seams or strands.28,29 Individual BCCs may contain multiple histological subtypes . Characteristic features of micronodular, morpheic, and infiltrative subtypes make it difficult to clinically delineate the borders of the lesion and hence they are often excised with inadequate margins, predisposing them to recurrence.28 In one case series of 51 morpheaform BCCs, the average subclinical extension was found to be 7.2 mm, while the average for clinically well-defined nodular lesions was 2.1 mm.31 Basosquamous carcinomas are BCCs that focally also show evidence of atypical squamous differentiation; they account for approximately 1% of all BCCs.28,29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree