Barrier Contraceptives and Spermicides

Michelle Forcier

KEY WORDS

Barrier contraception

Cervical cap

Cervical shield

Condoms

Contraceptive shield

Diaphragm

Female condom

Male condom

Spermicide

Sponge

Barrier methods of contraception include male condom, female condom (FC), cervical cap, cervical shield, sponge, and diaphragm. The addition of vaginal spermicides in the forms of gel, cream, foam, suppository, and film may offer some additional contraceptive benefits for these barrier methods. Both barrier methods and spermicides have fewer systemic side effects than hormonal contraceptive methods, but are significantly less efficacious, and are rarely recommended as the sole method of contraception for patients who wish to avoid an unwanted pregnancy. Barrier methods of contraception are most efficacious when used in addition to significantly more effective long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) implants or hormonal methods. Dual methods, that include either male or FCs, also provide superior protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) who elect to be sexually active. Barrier methods may both prevent physical contact and retain seminal fluids, thus effective for prevention of STIs, and block sperm from ascending into the uterus and upper tract. Barriers and spermicides are nonprescription and sometimes easier for AYAs to access over the counter. When patients elect to use barrier methods as their sole contraceptive, providers should offer detailed counseling and prescriptions for emergency contraception to improve potential contraceptive efficacy.

Condoms, the oldest and most common method of barrier contraception, still serve as a major form of birth control in the US, despite consistently higher failure rates than most other current contraceptive methods. Condoms are commonly used by AYAs, with data from 2006 to 2010 indicating that 96% of females use condoms followed by 57% withdrawal and 56% combined contraceptive pill.1 Self-reports of frequent use of condoms are encouraging, from the perspective of STI prevention and public health campaign efforts to reduce human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). However, the validity of self-reported condom use is suspect as studies demonstrate significant discordance between self-reports of 100% condom use and indicators of sperm presence in the vaginal tract.2

Data from the 2011 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) survey suggest that condoms are used at sexual debut in 68% of female teens, with younger teens (<14 years) less likely to use condoms (53% of females, 71% males) than older teens (17 to 18 years), including 80% and 86% of females and males, respectively. There appear to be no differences in condom use at first sexual encounter by race and ethnicity. Condoms are reported as a dual method in 15% of teens, with non-Hispanic White female teenagers having the highest rates of dual method use.1 Dual method rates may also be associated with nulliparity, insured status, and later sexual debut (>16 years).3

According to the 2014 NSFG report, 47.4% of women aged 15 through 24 use some form of contraception. Similar percentages of women aged 15 to 24 (10.1%) and 25 to 34 (11.5%) were using condoms. Rates of condom use for contraception are similar among Hispanic, Black and White youth aged 15 through 24 at 9%.4 In the high school sample from the 2013 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, a median of 53% females and 64% males used condoms at last intercourse.5 Among college students, the recent National College Health Assessment (NCHA) data suggest that similar use of condoms exists among young adults. Sixty-eight percent of college males and 61.6% of college females reported using condoms during last intercourse.6

Condoms for STI Prevention

Condom use has risen since the 1980s, related to public health campaigns to promote HIV prevention. Condoms are most protective for STIs transmitted in genital fluids that can be exchanged during penile intercourse. Condoms may also offer protection from bacterial exposure during oral and anal receptive sex as well as skin-to-skin viral transmission of disease. Latex and polyurethane condoms are impermeable to Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, trichomoniasis, syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV. Consistent use of condoms in heterosexual couples reduced transmission of HIV seroconversion by 80% or incidence 1.14/100 person-years “always” users versus 5.75/100 person-years for “never” users.7 Condoms also provide some measure of skin-to-skin barrier protection against viruses such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and human papillomavirus (HPV). Consistent and correct condom use demonstrated a 70% reduction in HPV transmission, improved clearance of HPV infection, decreased risk of genital warts and cervical cancer, and regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.8

An updated 2013 American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on condom use for AYAs readdresses these issues, recommending that pediatric providers:

Encourage communication between parents and adolescents about sexual activity and sex education with guidance from the American Academy of Pediatrics Bright Futures

Provide parent educational programs to create skills and incentives to talk to adolescent children about condom use

Improve condom availability in their medical home and in the community9

Uses of Male Condoms

Contraceptive Use

As a primary method of birth control, alone or in conjunction with a spermicide, a female barrier, hormonal method, or intrauterine contraception

As a backup method of contraception after a late start with a hormonal method, or whenever two or more combined oral contraceptive pills or one progestin-only pill have been missed

As a barrier contraceptive, used as part of the fertility awareness method (FAM) of contraception during vulnerable days of the woman’s cycle

Noncontraceptive Uses

To reduce transmission of STIs

To blunt sensation, to treat premature ejaculation

To reduce cervical antisperm antibody titers in women with associated infertility

To reduce allergic reaction in women with sensitivity to sperm

Types of Male Condoms

Latex condoms are most commonly used in the US. These are marketed in a variety of shapes and sizes, but typically measure 170 mm long and 50 mm wide, and 0.03 to 0.10 mm thick. Additional features such as ribbing, lubricants (spermicides, silicone, water-based gels), colors, scents, and tastes are marketing strategies, but are not linked to efficacy. In the past, sex educators promoted a “one-size-fits-all” concept to discourage some males from refusing to wear condoms because of self-reports of large penis size. More recent data suggest that size matters, and improved fit may improve condom use. In a sample of almost a thousand heterosexual men and women, 38.3% reported condom fit or feel problems that included decreased sensation, lack of naturalness, condom size complaints, decreased pleasure, and pain and discomfort.10 Condoms that fit poorly are more than two times more likely to break, slip, or interfere with erection, orgasm, and sexual pleasure. Additionally, males with poorly fitting condoms are twice as likely to remove a condom during intercourse than males with well-fitting condoms.11 Polyurethane condoms are made with nonbiodegradable materials that are stronger and less likely to be damaged by handling, petroleum lubricants, or shelf life. However, polyurethane condoms continue to be less popular than their latex counterparts as they are more expensive, less elastic and form fitting, and 2 to 5 times more likely to break or slip.12

Natural or skin (lamb cecum) condoms are as effective as latex or polyurethane condoms for pregnancy prevention, but not recommended for STI protection. Skin condoms have larger pores (up to 1,500 nm in diameter) that may allow HIV and hepatitis B virus transmission across these membranes. Skin or natural

condoms may not prevent STIs and are therefore not recommended for teens and young adults at high risk for STIs.13 Despite demonstrated drawbacks, nonlatex condoms remain an important barrier method for persons with sensitivities or allergies to latex.

condoms may not prevent STIs and are therefore not recommended for teens and young adults at high risk for STIs.13 Despite demonstrated drawbacks, nonlatex condoms remain an important barrier method for persons with sensitivities or allergies to latex.

Mechanism of Action

Condoms are sheaths that by covering the penis block transmission of semen, as well as other skin-to-skin infections. Condoms are regulated medical devices subject to testing by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Latex condoms manufactured in the US are tested electronically for holes before packaging. Consumer Reports regularly tests the US manufactured condom models for strength, reliability, and perforation. All models passed minimum standards for reliability, holes, and packaging with additional features not affecting failure or score. Consumer Reports did not find a single perforation in their “smart picks” selection of condoms even though industry standards do permit a limited number of defects per batch.12

Effectiveness

Condoms are currently the most efficacious way to prevent STIs in sexually active AYAs, but are inferior with respect to birth control in comparison to newer and LARC methods. The US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2013, does not reference a content section for condoms as a sole method of contraception, reflecting a shift highlighting condom use as a superior method for STI prevention, but inferior method for pregnancy prevention.14,15

Contraception counseling for all sexually active couples optimally focuses on dual methods such as hormonal or implant contraceptives for maximal pregnancy prevention supported by concurrent use of condoms to provide STI protection. The combination optimizes reproductive health outcomes in all sexually active AYAs. Estimates of dual method prevalence vary widely, with US rates consistently lower than Western Europe. Dual method research has focused on adolescent populations with associations including sociodemographics (age, race/ethnicity, education), risk perception, types of relationships, number of partners, relationship length, partner support of condoms, and exposure to HIV counseling and prevention.16 A 2013 study of 15- to 24-year-olds attending US family planning clinics demonstrated that one-third of AYAs reported condom use, with 5% dual method users. Women who used condoms before hormonal contraception and believed that their partner supported condom use were more likely to use dual methods over time.17

Perfect use is estimated with two condoms breaking per 100 condoms used. However, real life condom efficacy requires proper technique and application with each and every coitus. Condom failure rates are estimated between 15% and 21%, with only half of users continuing the method at 1 year.15,18 Condom failure typically results from lack of correct and consistent use as opposed to device failure in most instances.19

Improving Condom Success

Correct and consistent condom use over time is the key to efficacy. High rates of STIs in young women of color have led to a number of condom studies in this population. In one study of high risk African American women, aged 15 to 21, nearly 75% used condoms inconsistently.20 In another study of 824 sexually active students at historically Black colleges (51.8% female, 90.6% heterosexuals), 526 (63.8%) reported condom use at last coitus.21

Factors associated with decreased condom use include spontaneous intercourse with more casual sexual partners, not feeling at risk for HIV, lack of family connectedness, experience of interpersonal violence, and use of alcohol or other substances.22,23,24,25,26,27 Factors that have been linked to improved condom use include peer influence, knowledge about condom use and STI prevention, easy access to condoms (including carrying condoms on their person), and more open communication both with family and partners.23,26 Behavioral interventions that have been tailored to address cultural characteristics of individual populations have been effective in promoting condom use, but are not effective in promoting abstinence.28,29

A 2013 Cochrane review demonstrated that multiple sessions of social cognitive and health belief models over time were more likely to prevent second pregnancies and improve consistent condom use and use during last sex.29

Multiple studies have demonstrated condom availability programs effectiveness in the US including improved condom use and condom acquisition/condom carrying, delayed sexual initiation among youth, and reduced incident STIs.30,31,32,33 Comprehensive sex education programs increase condom and contraceptive use. Two-thirds of 48 comprehensive sex education programs demonstrated significant effects improving condom use.27 Behavioral interventions that have been tailored to address cultural characteristics of individual populations have been effective in promoting condom use, but are not effective in promoting abstinence.28 A 2013 Cochrane review demonstrated that multiple sessions of social cognitive and health belief models over time were more likely to prevent second pregnancies and improve consistent condom use and use during last sex.29

Improving consistent and correct use of condoms is essential to their ultimate effectiveness. Studies indicate that condom errors vary across time and populations assessed.19 Common errors that impair effectiveness include using condom during only part of penetrative activities; using incorrect placement techniques, including not squeezing air from the tip or leaving room at the tip; putting a condom on upside down; using lubricants that decrease condom integrity; and not removing the condom correctly. Studies demonstrate common issues with uncomfortable feel or fit, erectile dysfunction, slipping, leaking, or breaking are common and deterrents to regular use.

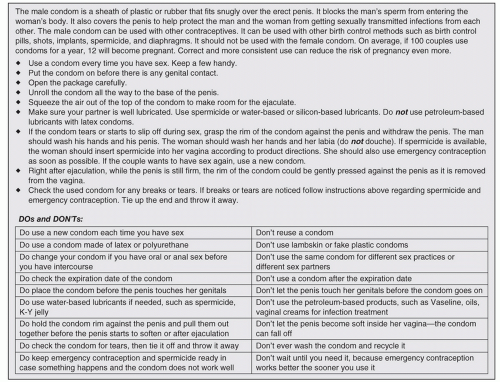

The following are some recommended tips for discussing correct and consistent condom use: (Fig. 42.1)

Ensure safe storage conditions (heat, expiration dates) along with privacy and easy access.

Plan how to integrate condom use during intercourse.

Follow techniques for opening and removing the condom from its package, as many as half of condom breaks occur before penetration.

Correct direction for unrolling condom, pinching tip to allow slack or remove air from reservoir, and pulling condom down over entire length of penis.

Continue to check placement of condom during the whole period of intercourse to assess slippage and integrity of device.

Use new condom for each orifice (oral, vaginal, anal).

Use only water-based or silicone lubricants applied to external surface of the condom, vulva or vagina (petroleum-based lubricants or medications can destroy condom integrity in less than a minute allowing viral or sperm transmission).

Correct condom removal includes grasping the rim of the condom at the base of the penis and carefully pulling off the condom while the penis is still partially erect or firm.

Inspect for signs of breakage or spillage. If concerned, consider emergency contraception or spermicide.

Advantages

Readily available without prescription and in many school, pharmacy, or retail settings

Relatively inexpensive costing between $0.50 and $1.50 each

Portable and easily carried by men and women for easy access in many settings

Male partner is included in contraception and family planning participation

Visible proof of protection during each act of coitus

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree