Barrett esophagus (BE) is a precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Developments in imaging and molecular markers, and endoscopic eradication therapy, are available to curb the increase of EAC. Endoscopic surveillance is recommended, despite lack of data. The cancer risk gets progressively downgraded, raising questions about the understanding of risk factors and molecular biology involved. Recent data point to at least 2 carcinogenic pathways operating in EAC. The use of p53 overexpression and high-risk human papillomavirus may represent the best chance to detect progressors. Genome-wide technology may provide molecular signatures to aid diagnosis and risk stratification in BE.

Key points

- •

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett esophagus (BE) have been considered to be the most important risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Emerging data indicate that high-risk human papillomavirus (hr-HPV) maybe an etiologic factor for a subset of Barrett dysplasia and EAC.

- •

The cancer risk in BE has to be managed and involves prevention (surveillance endoscopy), treating underlying GERD, and endoscopic therapy to remove diseased epithelium in appropriate patient subgroups.

- •

Potential markers of dysplasia or neoplasia in BE (eg, overexpression and hr-HPV) provide an opportunity to classify patients into high and low risk groups in relation to advancing to dysplasia and EAC and thus more intensive surveillance and targeted treatment.

Introduction

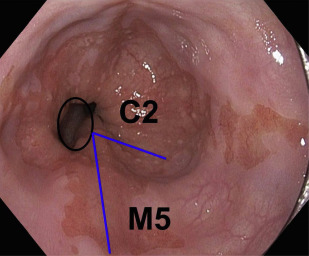

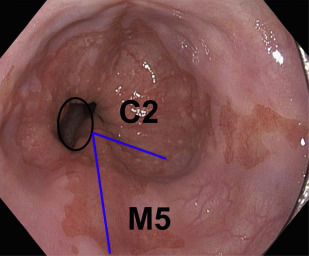

Advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of less than 15%. Conversely, patients with early-stage esophageal malignancy (stage of tumor [T]-1) (representing <10% of those undergoing esophagectomy) have a more than 90% survival rate at 5 years. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett esophagus (BE) are the most important known risk factors (as yet) for esophageal adenocarcinoma. In a study by Lagergren and colleagues, persons with chronic frequent and severe GERD symptoms had an odds ratio (OR) of 43.5 for EAC. Currently, BE is the only recognized visible precursor lesion for EAC with a malignant potential currently estimated at between 0.1% and 0.3% per annum. Esophageal cancers arising without an appreciable precursor lesion is a distinct possibility. BE is defined in most countries, including the United States, as displacement of the squamocolumnar junction proximal to the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) with specialized intestinal metaplasia on biopsy. The British Society of Gastroenterology definition differs in that it is an endoscopically apparent area above the esophagogastric junction that is suggestive of BE (salmon-colored mucosa), which is supported by the finding of columnar lined esophagus on histology ( Fig. 1 ). This definition negates sampling errors at index endoscopy, which may miss areas of intestinal metaplasia and thus preclude patients from entering endoscopic surveillance programs. There is a lower risk of malignant progression in patients without intestinal metaplasia (0.07% per year) compared with those with intestinal metaplasia (0.38% per year) on index biopsy.

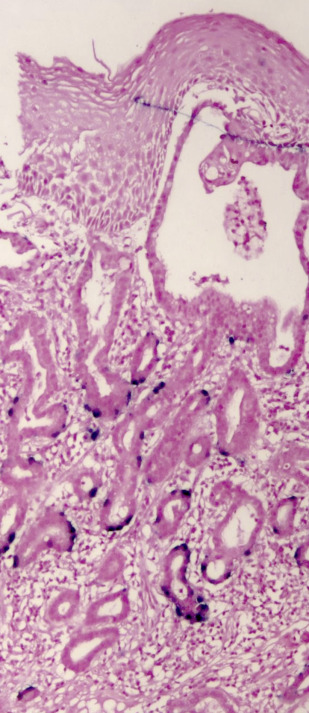

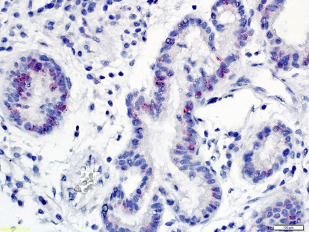

Other significant risk factors for EAC include central adiposity or BMI greater than 30, smoking, and family history of BE or EAC. More recently, high-risk (hr) human papillomavirus HPV (HPV) has been incriminated in a subset of patients with BE dysplasia and EAC ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). Importantly, distinct genomic differences have been found between HPV-positive and HPV-negative EACs. HPV-positive malignancies have approximately 50% less nonsilent mutations compared with virus-negative esophageal cancer. TP53 aberrations were absent in the HPV-positive EAC group, whereas 50% of the HPV-negative patients with EAC exhibited TP53 mutations. These data indicate different biological mechanisms of tumor formation. An earlier study found that Barrett dysplasia (BD) and intramucosal EAC samples positive for transcriptional markers of HPV activity were mostly devoid of p53 overexpression (>80%). Next-generation nucleotide sequencing revealed that almost all biologically active hr-HPV patients had detectable wildtype TP53, a hallmark of HPV-driven cancers, as is the case with cervical and head and neck malignancies. Together, the data suggest at least 2 different carcinogenic pathways operating in EAC as has been demonstrated in head and neck tumors.

Surveillance studies have demonstrated that esophageal cancer develops through a multistep pathway, the so-called Barrett metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. Despite endoscopic surveillance, the incidence of EAC has increased almost 6-fold in the United States between 1975 and 2001 (from 4 to 23 cases per million) and is thought to represent a real increase in burden rather than a result of histologic or anatomic misclassification or overdiagnosis. Recently, the rate of increase has diminished and plateaued in the United States and Sweden. This epidemic of EAC has occurred against a backdrop of progressive reduction in the risk estimate of malignancy associated with BE, throwing open the possibility of other causes, such as hr-HPV. It has been postulated that the exponential increase in EAC is due to increasing prevalence of GERD as a result of increasing abdominal adiposity (but the rate of increase has been greater than other cancers associated with obesity), reduced prevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori infection, and increased ingestion of refined food with a concomitant reduction in consumption of fruit and vegetables. It is possible that hr-HPV may be among the missing strong risk factors responsible for the significant increase of this malignancy since the 1970s. It parallels the dramatic 350% increase in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (a well-recognized HPV-driven cancer) in the same time frame.

Introduction

Advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of less than 15%. Conversely, patients with early-stage esophageal malignancy (stage of tumor [T]-1) (representing <10% of those undergoing esophagectomy) have a more than 90% survival rate at 5 years. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett esophagus (BE) are the most important known risk factors (as yet) for esophageal adenocarcinoma. In a study by Lagergren and colleagues, persons with chronic frequent and severe GERD symptoms had an odds ratio (OR) of 43.5 for EAC. Currently, BE is the only recognized visible precursor lesion for EAC with a malignant potential currently estimated at between 0.1% and 0.3% per annum. Esophageal cancers arising without an appreciable precursor lesion is a distinct possibility. BE is defined in most countries, including the United States, as displacement of the squamocolumnar junction proximal to the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) with specialized intestinal metaplasia on biopsy. The British Society of Gastroenterology definition differs in that it is an endoscopically apparent area above the esophagogastric junction that is suggestive of BE (salmon-colored mucosa), which is supported by the finding of columnar lined esophagus on histology ( Fig. 1 ). This definition negates sampling errors at index endoscopy, which may miss areas of intestinal metaplasia and thus preclude patients from entering endoscopic surveillance programs. There is a lower risk of malignant progression in patients without intestinal metaplasia (0.07% per year) compared with those with intestinal metaplasia (0.38% per year) on index biopsy.

Other significant risk factors for EAC include central adiposity or BMI greater than 30, smoking, and family history of BE or EAC. More recently, high-risk (hr) human papillomavirus HPV (HPV) has been incriminated in a subset of patients with BE dysplasia and EAC ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). Importantly, distinct genomic differences have been found between HPV-positive and HPV-negative EACs. HPV-positive malignancies have approximately 50% less nonsilent mutations compared with virus-negative esophageal cancer. TP53 aberrations were absent in the HPV-positive EAC group, whereas 50% of the HPV-negative patients with EAC exhibited TP53 mutations. These data indicate different biological mechanisms of tumor formation. An earlier study found that Barrett dysplasia (BD) and intramucosal EAC samples positive for transcriptional markers of HPV activity were mostly devoid of p53 overexpression (>80%). Next-generation nucleotide sequencing revealed that almost all biologically active hr-HPV patients had detectable wildtype TP53, a hallmark of HPV-driven cancers, as is the case with cervical and head and neck malignancies. Together, the data suggest at least 2 different carcinogenic pathways operating in EAC as has been demonstrated in head and neck tumors.

Surveillance studies have demonstrated that esophageal cancer develops through a multistep pathway, the so-called Barrett metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. Despite endoscopic surveillance, the incidence of EAC has increased almost 6-fold in the United States between 1975 and 2001 (from 4 to 23 cases per million) and is thought to represent a real increase in burden rather than a result of histologic or anatomic misclassification or overdiagnosis. Recently, the rate of increase has diminished and plateaued in the United States and Sweden. This epidemic of EAC has occurred against a backdrop of progressive reduction in the risk estimate of malignancy associated with BE, throwing open the possibility of other causes, such as hr-HPV. It has been postulated that the exponential increase in EAC is due to increasing prevalence of GERD as a result of increasing abdominal adiposity (but the rate of increase has been greater than other cancers associated with obesity), reduced prevalence rates of Helicobacter pylori infection, and increased ingestion of refined food with a concomitant reduction in consumption of fruit and vegetables. It is possible that hr-HPV may be among the missing strong risk factors responsible for the significant increase of this malignancy since the 1970s. It parallels the dramatic 350% increase in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (a well-recognized HPV-driven cancer) in the same time frame.

Epidemiology, genetics, and natural history of Barrett esophagus

BE affects predominantly white and South Asian men, and is associated with age older than 50 years, chronic GERD, hiatal hernia, and abdominal adiposity. This premalignant lesion is estimated to affect between 1.6% of the adult Swedish population and 6.8% of Americans. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of heartburn, esophagitis, and BE are well-documented. These racial differences; familial aggregation of GERD symptoms, BE, or adenocarcinoma; and twin studies suggest the possibility of a genetic component to GERD and BE. A study of GERD symptoms in 8411 Swedish twin pairs older than age 55 years found a casewise concordance for GERD of 31% among female monozygotic (MZ) twins compared with 21% in female dizygotic (DZ) twins.

Heritability was estimated to account for 30% of the liability to GERD. A British study of 1960 twin pairs to determine the relative contribution of genetic and environmental influences revealed that casewise concordance was significantly higher for MZ than DZ twins (42% v 26%; P <.001). Multifactorial liability threshold modeling suggested that 43% of the variation in liability to GERD was due to multiple small genetic effects.

Genome-wide association studies have found an association between BE and 2 variants on chromosome 6p21 (major histocompatibility complex [MHC]) and 16q24 compared with controls. The association of these variants with EAC was validated in another case-control study. Interestingly, in a small prospective study involving multiethnic South East Asian subjects, a strong association between HLA-B7 (0702/0706) (MHC class I) and BE in Indians (who have a white genetic make-up) compared with South Asian controls has been demonstrated. Furthermore, loss of MHC class I and gain of class II were observed to be early events in BE. Environmental factors (eg, H pylori infection) may be protective for BE in both Asians and whites.

In those patients with chronic GERD, the prevalence of BE is 10% to 15%. A large proportion of patients with BE are asymptomatic and almost all (>90%) never progress to EAC. Two large population-based studies have determined the risk estimate of cancer in nondysplastic BE (NDBE) to be between 0.12% and 0.13%.

The malignancy potential in Barrett low-grade dysplasia (LGD) is poorly defined due to poor interobserver correlation, biopsy sampling error, and regression of LGD as a result of immunosurveillance. The incidence of EAC among patients with Barrett LGD is estimated at between 0.5% and 0.6% per year. In a meta-analysis involving 4 studies that included subjects with high-grade dysplasia (HGD) but excluded prevalent cancers and those subjects with previous endoscopic and/or surgical intervention, the incidence of EAC was estimated to be between 5.6% and 6.6% per annum.

Predictors of progression (endoscopic, histologic, and molecular)

The longer the segment of BE, the greater the risk of progression to HGD or EAC. A multicenter study that enrolled 1175 subjects with NDBE with a mean follow-up of 5.5 years revealed that BE length predicted the risk of progression to HGD or EAC with an OR of 1.2. Every 1 cm increase in length resulted in a 28% greater risk for neoplasia.

Currently, dysplasia is considered the best (but imprecise) marker of cancer risk in BE. Given the shortcomings of dysplasia as a cancer risk stratification tool, especially in low-grade, as mentioned previously, several biomarkers have been proposed to predict the risk of malignant progression.

P53 immunohistochemistry has been proposed as a good clinical molecular marker for predicting disease progression in BD and, as such, has been recommended as an adjunct to routine clinical diagnosis by the British Society of Gastroenterology. Nevertheless, there is wide variability in positive staining for overexpression, in the order of between 50% and 90%. TP53 mutations due to frame-shifts, deletions, defective splice sites, or nonsense mutations can all result in absent p53 staining. HPV E6 oncoprotein-mediated degradation of TP53 is another cause of negative staining for p53 in BD or EAC. A recent discovery that hr-HPV is strongly associated with a subset of patients with BD and EAC should prompt further investigation in the use of biomarkers relating to viral transcriptional activity (p16INK4A, E6/E7mRNA) to identify the high-risk group of progressors to malignancy.

Chromosome instability (the most common cause of genomic instability) is strongly associated with progression from BE to EAC. A study involving 243 subjects with BE in whom esophageal biopsies were subjected to a chromosome instability biomarker panel consisting of 9p loss of heterozygosity (LOH) (inactivation of p16), 17p LOH (inactivation of p53), and aneuploidy or tetraploidy (DNA content abnormalities) revealed that those who tested positive for all of the above had a relative risk of progression to EAC of 38.7 (95% CI 10.8–138.5). Genetic clonal diversity in BE has been shown to predict progression to EAC even after controlling for genetic factors (eg TP53 and ploidy abnormalities). Specifically, 3 clones double the risk of progression to cancer. An increase in copy number and its variation, as well as catastrophic genomic events, have been shown to precede carcinogenesis in up to 32% of EAC cases.

Using a text-mining methodology, Kalatskaya determined that TP53 (p53), CDKN2A (p16INK4A), CTNNB1 (β-catenin), CDH1 (E-cadherin), GPX3 (glutathione peroxidase 3), and NOX5 (NADPH oxidase 5) were the top candidate genes involved in BE progression to cancer. These 6 functionally interrelated genes are involved in a diverse range of biological pathways, including DNA repair (TP53), cell cycle (TP53, CDKN2A), regulation of cell-cell adhesion or gene transcription (CTNNB1), cellular adhesion (CDH1), and detoxification of reactive oxygen species (GPX3, NOX5), and are subject to genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic alterations in a significant proportion of EACs.

Screening for Barrett esophagus

Patients at risk of EAC (ie, age 50 years or older, white, male, chronic GERD, hiatal hernia, abdominal adiposity and elevated body mass index, and family history of EAC) should be screened with either standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy or transnasal endoscopy. Nevertheless, there are no prospective, randomized, controlled trials demonstrating benefit in terms of decreasing the incidence or mortality of EAC or cost-effectiveness in screening for BE. Screening the general population with GERD for BE is not currently recommended and individualized screening has been suggested because reflux symptoms are not a reliable marker for BE.

Endoscopic surveillance of Barrett esophagus

Current management strategy is to enroll patients with BE into surveillance programs in an attempt to detect cancer at an early and potentially curable stage. The current recommendations for surveillance in BE are to perform endoscopy every 3 to 5 years. Patients with LGD who undergo endoscopic surveillance should do so at intervals of 6 to 12 months and those with HGD in the absence of eradication therapy should do so every 3 months. The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends endoscopic eradication therapy rather than surveillance for treatment of patients with HGD. The finding of dysplasia needs to be confirmed by an independent second pathologist to reduce interobserver variation. Patients with dysplasia should be on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy to reduce inflammatory changes that could make histopathological interpretation difficult.

Barrett esophagus evaluation

Assessment for BE is done if the squamocolumnar junction is located above the GEJ. BE is measured from the proximal (top) end of the longitudinal gastric folds at the GEJ to the area of columnar epithelium that terminates at the site of the squamocolumnar demarcation. BE has been traditionally defined as long segment (>3 cm) and short segment (≤3 cm). The Prague criteria have superseded it and identify the circumferential (C) and maximum (M) extent of Barrett metaplasia (see Fig. 1 ). It has been demonstrated to have excellent interobserver agreement among endoscopists (for columnar epithelium extending at least 1 cm above the GEJ). Endoscopic evaluation of the columnar-lined esophagus is carefully performed using high-resolution white light endoscopy or electronic or dye chromoendoscopy. Four quadrant biopsy specimens are obtained every 1 to 2 cm, as well as targeted biopsies of apparent lesions from patients with BE. In patients with known or suspected BD, 4 quadrant biopsy specimens are obtained every 1 cm. Specific biopsy specimens of any mucosal irregularity are sent separately to the pathologist for evaluation.

It is recommended that endoscopists who evaluate patients for BE using high-definition white light endoscopy spend an average of 1 minute per centimeter of BE before obtaining biopsies. It is unclear if inspection time is directly responsible for improved detection rates or a surrogate marker for more obsessive and observant endoscopists.

Management of underlying gastroesophageal reflux disease

- •

Life-style modification: weight loss, eating small frequent meals, avoiding acidic and spicy foods, and raising the head of the bed by 6 inches.

- •

PPIs are the mainstay of treatment.

- •

H2-receptor antagonists may be required to combat nocturnal acid breakthrough.

- •

Prokinetic therapy may help volume regurgitation. Domperidone is unavailable in the United States but metoclopramide is a suitable alternative. The use of cisapride has been severely restricted worldwide given its propensity to cause a fatal form of ventricular arrhythmia (torsades de pointes) in the presence of QT prolongation.

- •

Baclofen, a gamma-aminobutyric acid-B (GABA B ) receptor agonist reduces transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and may be effective in patients with upright reflux and belching. Its side-effect profile of drowsiness, dizziness, nausea or vomiting, seizures, and potential death on withdrawal has precluded its widespread use for refractory GERD.

- •

Almost all studies involving medical therapy for BE use either resolution of reflux symptoms or normalization of esophageal acid exposure as the endpoint. The former is a poor predictor of persistent acid reflux in patients with BE and there are insufficient data advocating esophageal pH monitoring to optimize PPI therapy to fully control reflux symptoms.

- •

An antireflux operation can be considered, most commonly a Nissen fundoplication, in patients with significant volume regurgitation or those responding to medical therapy but wanting a surgical alternative. This involves wrapping a portion of the gastric fundus around the distal esophagus and closing the crura (to prevent the esophagus sliding out). Surgical intervention should be preceded by pH-metry (to confirm pathologic reflux) and manometry (to exclude underlying esophageal motility problems). Early complications include pneumothorax, surgical emphysema, perforation, and transient dysphagia. Late postoperative complications are gas-bloat syndrome, dysphagia, and small bowel obstruction.

- •

It is worth noting that neither surgery nor medical therapy have been shown to prevent EAC.

Chemoprevention in Barrett esophagus

Indirect evidence exists to support the use of PPIs as a chemopreventive agent in BE. In a randomized control trial involving BE subjects treated with PPI versus histamine type II receptor blockers, there was an 8% regression in BE surface area in the former group. An inverse correlation has been established between long-term use of PPIs and the incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in BE. Nevertheless, there are no prospective clinical studies demonstrating that PPI therapy prevents the development of dysplasia and progression to cancer.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

A meta-analysis of 9 clinical studies has shown a 43% decreased rate of esophageal cancer in subjects who use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A 50% reduction of esophageal malignancy was seen with aspirin use. In a prospective study involving 350 subjects with BE followed up for a median of 65.5 months, there was a reduced risk of EAC in current users of NSAIDs (hazard ratio 0.20, 95% CI 0.10–0.41) versus subjects who had never used these drugs. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 and immunomodulation by NSAIDs has been postulated as the mechanism for the prevention of progression of BE to adenocarcinoma. A negative study involving a cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAID and BE was reported by Heath and colleagues. The Aspirin Esomeprazole Chemoprevention Trial (ASPECT) in BE is currently investigating if treating with aspirin and high-dose PPIs can reduce progression from metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma and hence reduce mortality. In the interim, it is appropriate to consider prescription of low-dose aspirin for BE subjects (who are already on a PPI) with concomitant risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Statin use is associated with a lower risk of cancer in patients with BE. A meta-analysis revealed a 41% reduction in the risk of EAC in 2125 subjects with BE (number needed to treat = 389). In a recently published nested case (EAC, n = 311) control (n = 856) study, statin use was inversely associated with development of EAC (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.47–0.91).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree