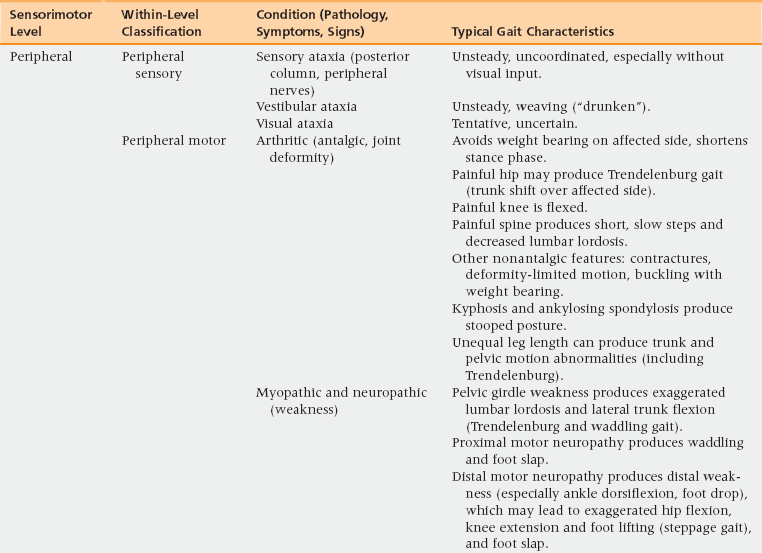

19 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Discuss the prevalence of gait/mobility deficits in older adults. • List some of the deleterious impacts of gait disorders on the health of older adults. • Discuss three risk factors for gait/mobility deficits in older adults. • Describe common diagnoses and impairments contributing to gait disorders in older adults. • Formulate a differential diagnosis to determine the cause of a gait disorder in the older adult. • Describe and discuss some of the low-tech performance-based measures used to evaluate gait and mobility in the older adult. • Describe and discuss some of the management options, including treatment outcomes, for gait and mobility deficits in the older adult. The term mobility may encompass a variety of functional activities, such as transfers to and from a bed and chair, walking, stair climbing, getting in and out of vehicles, and others.1 Difficulty ambulating and problems with general mobility are frequent complaints of older adults. Each year about 1 in every 100 older adults develops new severe mobility disability, defined as the inability to walk across a small room or the need for help from another person to do so.2 Approximately 20% of noninstitutionalized older adults admit to having trouble walking or require assistance from another person or equipment to ambulate,3 and the prevalence of walking limitations in noninstitutionalized adults 85 years and older can exceed 54%.3 Finally, clinically abnormal gait, particularly with a neurologic etiology (identified later in this chapter), is associated with falls.4 The impact of gait and mobility deficits can be devastating for the older adult. Impairments in gait and mobility are associated with depressive symptoms,5 falls,6 functional dependence,7,8 institutionalization,9 and death strength of evidence (SOE) = B).1,7 Many adults maintain normal or near normal gait and mobility well into old age. Thus gait and mobility dysfunctions are not an inevitable consequence of aging, as is often thought, but in many cases are a reflection of chronic diseases10 or of recent or remote trauma. Age-related declines in gait speed are well documented, and are a result of decreases in stride length, rather than decreases in cadence (steps per minute).11 Shorter, broader strides, longer stance, and shorter swing durations are some of the gait characteristics apparent after age 75 or 80.12,13 Often the cause of a gait disorder is multifactorial. In one community-based sample, the prevalence of abnormal gait was 35%, split approximately evenly between neurologic and nonneurologic etiologies.9 A number of diseases and impairments (Table 19-1) may contribute to decreases in gait speed, including cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal disease, reduced leg strength, poor vision, diminished aerobic function, balance problems, physical inactivity, joint impairment, previous falls, and fear of falling.15–21 Other less common factors contributing to gait disorders include metabolic disorders related to renal or hepatic disease, tumors of the central nervous system, subdural hematoma, depression, and psychotropic medications. Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism and B12 and folate deficiency may also be associated with reversible gait disorders.11 Coimpairments, such as when leg weakness is found in the patient with balance deficits, may have a greater effect on deficits in mobility than the sum of the single impairments.15 TABLE 19-1 Diagnoses Contributing to Gait Abnormalities in Primary Care Geriatrics Adapted from Hough JC, McHenry MP, Kammer LM. Gait disorders in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 1987;35(6):191-6. One way of organizing a differential diagnosis for a gait disorder is to consider three levels of sensorimotor function—peripheral, subcortical, and cortical. Table 19-2 outlines for each of the three sensorimotor levels the most common conditions and gait characteristics associated with each condition.22 To this must be added consideration of diseases of other organ systems that commonly affect gait. Finally, one must consider whether medication-related effects are contributing. TABLE 19-2 Classification of Gait Disorders by Sensorimotor Level Adapted from Alexander NB. Differential diagnosis of gait disorders in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 1996;12(4):689-703. • Trendelenburg gait (hip abductor weakness causing weight shift over the weak hip) • Antalgic gait (avoidance of excessive weight bearing and shortening of stance on one side because of pain) • Steppage gait (excessive hip flexion facilitating foot clearance of the ground in patients with foot drop caused by ankle dorsiflexor weakness) • Diseases causing spasticity (such as those related to myelopathy, B12 deficiency, and stroke) • Parkinsonism (idiopathic as well as drug-induced) Classic gait patterns appear when the spasticity is sufficient to cause leg circumduction and fixed deformities (such as equinovarus), when parkinsonism produces shuffling steps and reduced arm swing, and when cerebellar ataxia increases trunk sway sufficiently to require a broad base of gait support. Recent attention has focused on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and therapy for freezing of gait (FOG), found commonly in parkinsonian syndromes.23 Cerebrovascular insults to the cortex and/or basal ganglia and their interconnections may relate to gait ignition failure and apraxia.24,25 Cognitive, pyramidal, and urinary disturbances may also accompany the gait disorder. Gait disorders that might fall in this category have been given a number of overlapping descriptions, including gait apraxia, marche à petits pas, and arteriosclerotic (vascular) parkinsonism. A vascular etiology has been proposed linking not only slowed gait and impaired cognitive (executive) function, but depressive symptoms as well.26 A number of studies have found age- and disease-associated deficits in gait speed, often using a measure of gait variability, particularly while performing a simultaneous cognitive task (dual tasking such as talking while walking). These deficits are linked to increased fall risk. Even mild cognitive impairment (either amnestic or executive) is associated with changes in gait, such as in variability.27 Note that whereas declines in cognitive function, and executive function in particular, are associated with declines in gait speed, declines in gait speed can also predict declines in cognition.28 Patients consider pain, stiffness, dizziness, numbness, weakness, and sensations of abnormal movement to be the most common impairments contributing to walking difficulty.14 In many cases, the older adult presents with a gait disorder as a manifestation of acute or chronic disease (or in some cases, multiple diseases). Thus the aim of the primary care practitioner should be to diagnose the underlying disease state to determine whether the gait disorder is cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, or neurologic in etiology, or a result of some other pathology. Components of the clinical assessment can include the traditional history and physical examination, performance-based assessments, and laboratory and imaging tests. All of these will assist the primary care practitioner in formulating a clinical and/or impairment-based diagnosis as it relates to the gait dysfunction. A systems review is conducted to elucidate the multiple factors potentially contributing to the gait disorder. Systemic evaluation should include evaluation for acute cardiopulmonary disorders such as myocardial infarction, and other acute illness such as sepsis, because an acute gait disorder may be the presenting feature of acute illness in the older adult. Subacute and chronic cardiopulmonary disorders with dyspnea on exertion may also be present. Review auditory and visual systems, enquiring as to hearing and visual impairments, including Meniere’s disease, vertigo, cataracts, and glaucoma. For the neurologic and musculoskeletal systems, inquire as to the following: lower extremity sensory changes including numbness and tingling, joint and muscle pain, stiffness, joint instability or muscle weakness limiting the patient’s mobility during performance of daily activities such as ambulation, and poor balance and unsteadiness including dizziness during upright posture and gait. Evidence of subacute metabolic disease (such as thyroid disorders) also warrants evaluation. The physical examination should entail a thorough evaluation of the patient’s gait pattern, and should begin when the patient enters the room.29

Balance, gait, and mobility

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Primary Diagnosis Contributing to Gait Disorder

Percentage of Cases

Osteoarthritis or an inflammatory arthritis

43

Sensory imbalances (e.g., peripheral neuropathy)

9

Parkinsonism

9

Orthostatic hypertension

9

Intermittent claudication

6

Postcerebrovascular accident

6

Congenital deformity

6

Postorthopedic surgery

3

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency

3

Heart disease

3

Idiopathic gait disorder: fear of falling

3

TOTAL

100

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Approach to patient assessment

History and physical examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Balance, gait, and mobility