Axillary Space Exploration and Resections

James C. Wittig

Martin M. Malawer

Kristen Kellar-Graney

BACKGROUND

The axilla is a common site for primary soft tissue sarcomas as well as for metastatic disease that involves the axillary lymph nodes, such as advanced breast cancer or melanoma.

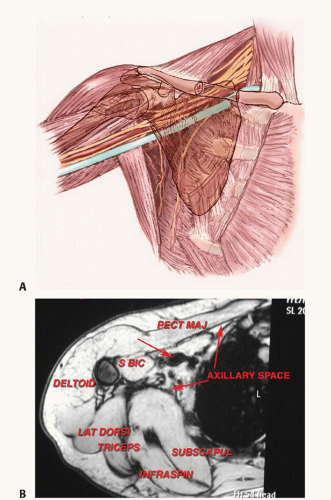

Sarcomas typically arise from the muscles defining the axillary space (FIG 1). Occasionally, however, they may arise directly from the brachial plexus or axillary vessels (eg, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, neurosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma). Several types of malignant tumors may involve the axillary space and may require surgical resection. Primary sarcomas occur within the muscles (ie, the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and subscapularis muscles) that make up the borders of the axillary space. Rarely do they develop within the axillary fat itself. More commonly, large metastatic deposits to the regional lymph nodes create large, matted masses that may require resection. The most common of these are metastatic melanoma and recurrent breast carcinoma. In addition, there are primary tumors that arise from the brachial plexus, either the nerves or the vessels. These include leiomyosarcomas of the axillary vein and neurofibrosarcomas of the adjacent nerves.

Small masses may be clinically silent, but large masses inevitably will result in significant pain or loss of function due to involvement of the brachial plexus.

Venous occlusion may be seen in neglected, massive tumors and is a harbinger of loss of limb and possibly even of life due to gangrene.

Historically, surgical management of tumors in this location consisted of forequarter amputation; advances in radiographic imaging, adjuvant therapies, and surgical techniques have greatly improved our ability to perform limb-sparing resections in this location.4 The key to adequate and safe surgical resection of axillary tumors is the complete visualization and mobilization of the infraclavicular portion of the brachial plexus and the axillary artery and vein and the cords that surround them.1,2 In general, imaging studies of the axillary space are not reliable for determining vascular or nerve sheath involvement. Multiple imaging studies are required, but the ultimate decision to proceed with a limbsparing surgery is based on the intraoperative findings at the time of exploration.1,2,4,5

Axillary tumors extending along the chest wall often can be elevated off the underlying ribs; however, tumor extension into the intercostal spaces may require thoracotomy and rib resection to ensure adequate margins.

ANATOMY

The axilla is a pyramid-shaped space between the chest wall and the arm defined by its surrounding muscles; it appears triangular when seen from either the coronal or axial views.

The superior apex of the pyramid is formed by the junction of the clavicle and the first rib, approximately 1 to 2 cm medial to the coracoid process.

The muscular boundaries of the axilla consist of the pectoralis major muscle anteriorly; the subscapularis, teres major, and latissimus dorsi muscles posteriorly; and the coracobrachialis, short head of the biceps, and triceps muscles laterally.

Vital structures in the axilla include the major branches of the infraclavicular portion of the brachial plexus and the

axillary vessels. Any surgery in this region requires detailed knowledge of and familiarity with these structures.

Infraclavicular brachial plexus

The lateral, posterior, and medial cords of the infraclavicular brachial plexus are found at the level of the pectoralis minor muscle, where they then give rise to five major branches: the median, ulnar, radial, musculocutaneous, and axillary nerves. The cords and branches run along the axillary vascular sheath as it passes through the axilla.

The lateral cord gives rise to the musculocutaneous nerve, which travels along the medial aspect of the conjoint tendon, where it innervates the coracobrachialis and short head of the biceps. This nerve is the first to be identified during the exploration because it is located in the superficial axillary fat inferior to the coracoid process. The largest portion of the lateral cord combines with the medial cord to create the median nerve.

The posterior cord gives rise to the axillary nerve, which travels deep in the space and passes inferior to the glenohumeral joint and subscapularis muscle, where it innervates the deltoid muscle. The main portion of the posterior cord becomes the radial nerve, which travels posterior to the sheath and exits the axillary space along with the axillary sheath.

The medial cord gives rise to the ulnar nerve, which travels along the most medial aspect of the sheath and exits distally along with the sheath. Because of its medial position along the sheath, the ulnar nerve is the nerve most commonly involved by tumors arising inferior to the brachial plexus, which can present with symptoms of either weakness or neuropathic pain. The median nerve, formed by a combination of the lateral and medial cords, is found on the lateral aspect of the sheath and exits the inferior aspect of the axillary space along the sheath.

Axillary vessels

The axillary artery and vein are the continuation of the subclavian vessels, changing name as they enter the apex of the axilla below the clavicle and first rib. These vessels run in a single sheath, surrounded by the cords of the brachial plexus. The vessels pass through the axillary space medial to the coracoid to the medial aspect along the humeral shaft. Distal to the teres major, the vessels are renamed the brachial vessels. Major vascular branches in the axillary space include the thoracoacromial artery (with its pectoral, deltoid, clavicular, and acromial branches), the lateral thoracic artery, the subscapular artery, and the anterior and posterior humeral circumflex vessels.

Lymphatics

A substantial amount of fat surrounds the vascular sheath as it runs through the axilla along with the lymphatics and lymph nodes. Major clusters of lymph nodes are found along the brachial and axillary vessels, the lateral thoracic vessels (anterior axillary nodes), and the subscapular vessels (posterior axillary nodes). Axillary tumors may arise from lymph node metastases anywhere along the axillary vessels; the most common sites are nodes along the distal portion of the axillary vessels.

INDICATIONS

Any mass in the axillary space should be considered for biopsy or resection given the propensity for malignant tumors to develop in the axilla and the predictability of neurogenic pain arising from continued tumor growth.

Palpate radial and ulnar pulses and inspect for venous congestion or swelling. Consider venography to evaluate loss of venous drainage indicative of tumor involving the brachial plexus.

Diminution of arterial flow is a late sign indicative of potential loss of limb—consider forequarter amputation.

Test sensation and strength of the axillary, radial, median, and ulnar nerves. Loss of nerve function typically is a very late finding indicative of major tumor involvement of the brachial plexus—consider forequarter amputation.

Infraclavicular brachial plexus and vascular exploration is mandatory before resection is attempted. Tumor involvement of these structures usually indicates that a forequarter amputation is required.4

IMAGING AND OTHER STAGING STUDIES

Three-dimensional imaging of the axillary space is important for accurate anatomic tumor localization and surgical planning. Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), angiography, and three-phase bone scans are used in the same manner as in other anatomic sites. In addition, we have found that venography (of the axillary and brachial veins) is essential to the evaluation of tumors of the axilla and brachial plexus in patients where the decision regarding limb-sparing surgery is conflictive.8

Plain Radiography

Careful inspection of posterior-anterior chest, anterior shoulder, and axillary view radiographs may reveal the presence of increased soft tissue density corresponding to an axillary mass.

Bone involvement and the presence of calcifications in the soft tissues should be noted.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

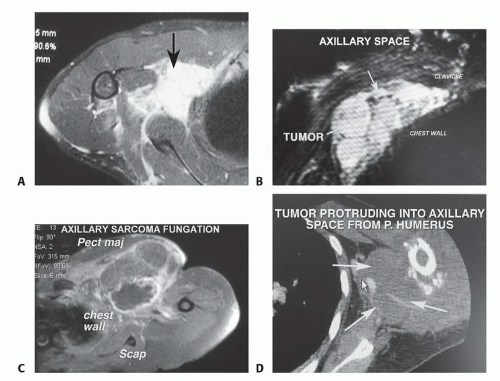

Multiplanar MRI is extremely helpful in visualizing the anatomic contents of the axillary space and defining the anatomic extent of the tumor (FIG 2A-C).

Axial CT imaging, with administration of intravenous (IV) contrast, demonstrates the major vascular structures, outlines the major muscle planes, and can detect subtle matrix formation within the tumor. CT is most useful in evaluating the bony walls of the axilla, specifically the humerus, glenohumeral joint, and scapula (FIG 2D).

Certain tumors, such as lipomas or hemangiomas, may have characteristic findings on T1- and T2-weighted MRI sequences suggestive of the proper histologic diagnosis. The presence or absence of lymphatic involvement should be noted, particularly in patients with a history of metastatic carcinoma.

Although the brachial plexus may be difficult to visualize, particularly when tumors distort or compress the surrounding fatty planes, the anatomic relationship of the nerve sheath to the vessels helps pinpoint their location.

Although CT imaging of the lungs is routinely performed as part of patient staging, the chest wall should always be inspected carefully to rule out tumor involvement of the rib cage and pleural cavity.

Nuclear Imaging

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, particularly when fused with MRI or CT imaging data, may significantly

improve the ability to detect lymphatic spread of tumor in and around the axilla. Standardized uptake values (SUV) correlate with tumor metabolism and may help to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions.

FIG 2 • Imaging studies of the axillary space. A. T2-weighted MRI scan showing a large mass (arrow) occupying the axillary space. B. Coronal T2-weighted MRI scan showing a large tumor below the pectoralis major that fills the entire axillary space, from the clavicle to the lower end of the base of the pyramid that forms the axillary space. C. Axial MRI scan of a large fungating tumor from the axillary space. There are no muscle or skin components adjacent to the tumor, which protrudes anteriorly. D. CT scan of a primary bony sarcoma with a large extraosseous component that extends into the axilla. This finding is an excellent indication for the use of the anterior portion of the utilitarian incision for resections of large tumors of the proximal humerus. It demonstrates that the axillary space must be completely visualized and that the vessels must be mobilized.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|