BACKGROUND

Diabetic neuropathy is one of the commonest long-term complications of diabetes. The prevalence of neuropathy increases with age and duration of diabetes, and may be the presenting feature of Type 2 diabetes. The diabetic neuropathies are diverse, affecting different parts of the nervous system and presenting with various clinical manifestations. Most common among the neuropathies are a chronic sensorimotor distal symmetric polyneuropathy (DPN) and the autonomic neuropathies. Central to the development of all diabetic complications is poor glycemic control. The presence of neuropathy is frequently coexistent with other diabetic complications. Other forms of neuropathy, including chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, B12 deficiency, hypothyroidism, and uremia can occur more frequently in diabetic patients and should always be excluded.

Diabetic neuropathies can be classified into:1

- Generalized symmetric polyneuropathies:

° Acute sensory: characterized by the acute onset of severe sensory symptoms; rare and may follow periods of poor metabolic control (e.g., ketoacidosis)

° Chronic sensorimotor: characterized by aching or burning pain, electrical or stabbing sensations, paresthesia and hyperesthesia, typically worse at night; the symptoms are most commonly experienced in the feet and lower limbs

° Autonomic: cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, urinary, sweating, and metabolic disturbances

- Focal and multifocal neuropathies:

° Cranial

° Truncal

° Focal limb

° Proximal motor (amyotrophy).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NEUROPATHY

Hypotheses concerning the multiple etiologies of diabetic neuropathy include a metabolic insult to nerve fibers, neurovascular insufficiency, autoimmune damage, and neurohormonal growth factor deficiency.2 Several different factors have been implicated in this pathogenic process. Hyperglycemic activation of the polyol pathway has been shown to lead to an accumulation of sorbitol and potential changes in the NAD: NADH ratio. This may lead to direct neuronal damage and/or decreased nerve blood flow.3 Increased oxidative stress, and the resultant increase in free radical production, may lead to vascular endothelial damage and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability.4 Alternatively, excess nitric oxide production may result in the formation of peroxynitrite with damage to endothelium and neurons.5 Other investigators have proposed that autoimmune mechanisms play a role in some diabetic subjects.6 The result of this multifactorial process may be activation of polyADP ribosylation depletion of ATP, resulting in cell necrosis and activation of genes involved in neuronal damage.7

DIABETIC AUTONOMIC NEUROPATHY

The American Diabetes Association has defined DAN as: “A neuropathic disorder associated with diabetes that includes manifestations in the peripheral components of the autonomic nervous system”.1

DAN is one of the least familiar and most poorly studied complications of diabetes despite being common and having a significant negative impact on survival and quality of life in people with diabetes.2 As highlighted above, diabetic autonomic neuropathy is a subtype of the generalized symmetric polyneuropathies that can accompany diabetes and can involve the entire autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system has vasomotor, visceromotor, and sensory fibers which innervate every organ. Alterations in this innervation result in dysfunction in one or more organ systems (e.g. cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, sudomotor or ocular), which can be either clinical or subclinical.1 Most organs have dual innervation and receive fibers from both the parasympathetic and sympathetic parts of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). As the vagus nerve (the longest of the ANS nerves) accounts for approximately 75% of all parasympathetic activity, and as DAN appears to affect longer nerves more quickly than shorter nerves, even early effects of DAN are wide-spread.1 The onset of DAN is variable and often symptoms, or subclinical alterations in organ function, are not apparent until long after the onset of diabetes. However, as with most other microvascular complications of diabetes, which are almost invariably present simultaneously, DAN appears to be more intimately related to glycemic control than duration of diabetes per se.8,9 Subclinical autonomic dysfunction can occur within a year of diagnosis in patients with Type 2 diabetes and within 2 years of onset in Type 1 diabetes.10

Prevalence

The prevalence of DAN in the general diabetic population ranges from 1.6% to 90%, depending on the diagnostic tests used, population examined and the type and stage of disease.1 Low et al11 reported a prevalence of mild autonomic impairment (defined as a composite autonomic severity score of <3 using a validated self-report instrument [Autonomic Symptom Profile]) in 54% of patients with Type 1 and 73% in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy (CAN) is the most clinically important and well-studied form of DAN because of its association with a variety of adverse outcomes, including cardiovascular death. Relatively low prevalence rates of CAN (7.7%) were reported among newly diagnosed patients with Type 1 diabetes, when strict diagnostic criteria were used;12 however, in patients awaiting pancreatic transplants, prevalence rates were as high as 90%.13 Gastrointestinal features of DAN appear to be more common. Cross-sectional studies have suggested that approximately 50% of diabetic outpatients with long duration of diabetes have delayed gastric emptying and up to 76% have one or more gastrointestinal symptoms, the most common of which is constipation.14,15 Bladder dysfunction has been reported in 43-87% of individuals with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic women have a five-fold higher risk of unrecognized voiding difficulty compared with nondiabetic women.1

Problems associated with diabetic autonomic neuropathy

DAN can affect several organs, resulting in cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, urinary, sweating, pupillary, and metabolic disturbances. As many of these symptoms are common both during and outwith pregnancy, autonomic neuropathy may go unnoticed by both the patient and her doctors. A summary of the symptoms, diagnostic tests, and possible treatment options for DAN is shown in Table 18.1.

Gastrointestinal features

The gastrointestinal features are as follows:

- Esophageal enteropathy: disordered peristalsis, abnormal lower esophageal sphincter function

- Gastroparesis diabeticorum: non-obstructive impairment of gastric propulsive activity, associated with vomiting and early satiety

- Diarrhea: impaired motility of the small bowel (bacterial overgrowth syndrome), increased motility and secretory activity (pseudocholeretic diarrhea)

- Constipation (dysfunction of intrinsic and extrinsic intestinal neurons, decreased or absent gastrocolic reflex)

- Fecal incontinence: abnormal internal anal sphincter tone, impaired rectal sensation, abnormal external sphincter.

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is very common among diabetic subjects and can be associated with both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Prevalence rates of 30-50% have been reported. Gastrointestinal symptoms are very common in pregnancy, especially in the first trimester, among women both with and without diabetes. In diabetic women these symptoms, particularly vomiting, may be exacerbated by DAN.

Clinical features of gastroparesis include early satiety, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, epigastric discomfort, and bloating. Episodes of nausea or vomiting may last days to months or occur in cycles.16 Gastric emptying largely depends on vagus nerve function, which can be severely disrupted in DAN. Radiographic gastric emptying studies can establish definitively the diagnosis of gastroparesis, but are not practical in pregnancy. A pragmatic approach during pregnancy is therefore to attempt to exclude other known causes of vomiting, e.g. hyperemesis gravidarum, gastro-oesophageal reflux, infection or peptic ulceration. Diabetic gastroparesis during pregnancy can exacerbate nausea and vomiting, cause nutritional problems, alter the absorption of pharmacologic agents and create difficulty with glucose control. Therefore, in pregnant diabetic women with severe nausea and vomiting and/or erratic blood glucose control, gastroparesis should always be suspected.

As highlighted above, nausea and vomiting are very common in pregnancy, ranging from mild to severe and unremitting with dehydration and weight loss. In a woman with diabetes, gastroparesis may contribute to the etiology of intractable vomiting. Gastroparesis may be exacerbated by pregnancy with catastrophic consequences. In addition to the case presented above, several others have been reported describing the severe impact of gastroparesis on pregnancy management and outcome.17–19 Hare reported a case of severe nausea and

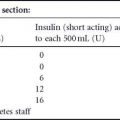

Table 18.1 Summary of symptoms associated with diabetic autonomic neuropathy, potential diagnostic tests, and therapeutic options in pregnancy.

| Symptom | Diagnostic tests | Treatment options |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Gastroparesis, erratic glucose control | Gastric emptying study, barium study (investigations outside pregnancy) | Frequent small meals, prokinetic agents (metoclopramide, domperidone, erythromycin) |

| Abdominal pain or discomfort, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, belching, bloating | Exclude metabolic disorders: thyroid function, celiac profile, B12 and folate, serum cortisol, autoimmune screen (gastric parietal cell and adrenal antibodies) may be considered)Endoscopy may be considered | Antibiotics, antiemetics, bulking agents, tricyclic antidepressants, pancreatic enzyme supplements, enteral feeding |

| Constipation | High-fiber diet and bulking agents, osmotic laxatives, prokinetic agents | |

| Diarrhea, often nocturnal alternating with constipation and incontinence | Soluble fiber, gluten and lactose restriction, cholestyramine, antibiotics,pancreatic enzyme supplements | |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Exercise intolerance, early fatigue and weakness with exercise | ECG, HRV (see Table 18.2) | Graded supervised exercise, beta-blockers |

| Postural hypotension, dizziness, light headedness, weakness, fatigue, syncope |