Liposarcoma (LPS) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma, frequently found in the thigh and retroperitoneum. LPS is commonly classified into well-differentiated LPS and dedifferentiated LPS. Histologic subtype, tumor location, and completeness of surgical resection are important prognostic indicators for LPS. Magnetic resonance imaging best characterizes extremity lesions, whereas computed tomography is most often used for intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal tumors. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment. Adjuvant radiation is considered for close margins. Survival for extremity tumors is favorable. However, difficulty in obtaining wide margins in the retroperitoneum predisposes to local recurrence and, ultimately, death from unresectable disease.

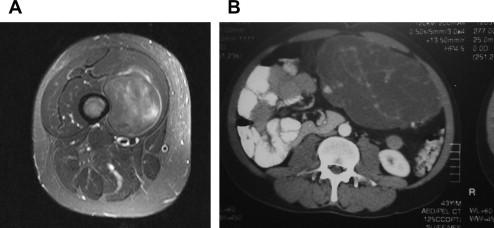

According to the National Cancer Institute, soft tissue sarcomas (STSs) make up less than 1% of newly diagnosed cancers, with an incidence of 2.5 per million. Liposarcoma (LPS) accounts for 24% of extremity and 45% of retroperitoneal STSs. LPS often remains asymptomatic until quite large. When symptoms occur, they can be vague and frequently caused by mass effect. LPSs can arise from any adipose tissue but are most commonly found in the thigh and retroperitoneum ( Fig. 1 ). Like other STSs, prognosis varies depending on the site of origin, tumor size, depth, and grade. Recurrence rates range from 5% to 83%, with mortality rates from 1% to 90%. First and foremost, the proper histologic classification is critical because this (along with tumor location) affects recurrence and survival. LPS has a diverse array of subclassifications; the biology is quite different and terminology can be controversial, confusing, and sometimes misleading.

Pathologic classification of adipocytic tumors

The pathologic classification of LPS in the overall spectrum of disease is represented by subtle nuances from low-grade to high-grade tumors, histologically classified based on their differentiation. Low-grade or well-differentiated LPS (WDLPS) consists of mature fat with the presence of lipoblasts, enlarged atypical nuclei, and clear multivacuolated cytoplasm and has been characterized by the amplification of chromosome 12q 13–15. Lipoblasts represent the hallmark of any malignant adipocytic tumor.

Atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT) and WDLPS are sometimes synonymous terms used for a low-grade LPS and represent about 40% to 45% of all LPS. Because WDLPS does not show metastatic potential unless associated with dedifferentiation and because wide excision is often curative, the term ALT was introduced. However, there is controversy regarding when this term is appropriate. Morphologically and genetically, ALT and WDLPS are identical. Some investigators believe it is a pathologic diagnosis based on histology, others think it should be a combination of histology and anatomic location (eg, the extremity), and some suggest it should be reserved only for the appropriate histology and a clinically indolent course.

On the other side of the biological spectrum, there are definitive criteria when an LPS should be classified as a dedifferentiated LPS (DDLPS): the presence of more than 5 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields. But tumor subclassification can be challenging because of the presence of fibrous tissue, myxoid tissue, varying degrees of cellularity, and lower numbers of mitotic figures. Problems with classification also arise when the tumor has more mitotic figures and cellularity than would be typical for a WDLPS diagnosis but less than for a DDLPS. Fibrous and/or myxoid zones can range from minimal to dominant. Some studies have expanded the subclassifications to form a spectrum between WDLPS and DDLPS such as a low-grade dedifferentiation category. However, the true biological nature of this classification as being separate from WDLPS has yet to be proved.

Evans found that location and classification were the most important prognostic indicators for LPS; centrally based (deep) LPS and DDLPS had a worse prognosis than peripheral (superficial) LPS and WDLPS. These distinctions become important when counseling a patient on treatment, recurrence, metastatic risk, and survival. Low-grade variants have a 5-year survival of 90% versus survival rates for high-grade variants as low as 30% to 75%. These tumors frequently recur, and a WDLPS can undergo dedifferentiation to become a DDLPS on recurrence. The risk of dedifferentiation is time dependent and occurs approximately 20% of the time for retroperitoneal tumors and 5% for extremity tumors. These rates increase with additional recurrences.

Clinical evaluation of WDLPS

Because LPS is rare, patients should be considered for referral to a multidisciplinary team with specific STS expertise. All patients need to undergo imaging to determine tumor size, exact location, as well as contiguity or proximity to nearby critical structures. This is best accomplished by computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both modalities have been shown to accurately predict tumor size and location relative to bone, joints, and neurovascular structures. MRI can more accurately delineate anatomic compartments and muscle involvement. Therefore, it is thought to be better for extremity tumors. CT is preferentially used for central tumors (of the abdomen or retroperitoneum). It also provides very accurate information more rapidly and with less cost than MRI.

Imaging characteristics have been described to differentiate WDLPS from DDLPS. Fat signal intensity is dominant in WDLPS. Conversely, imaging often reveals a heterogeneous nonlipogenic mass for DDLPS. Imaging characteristics aside, a pathologic diagnosis is still necessary before planning treatment. Core needle biopsy is preferred, but, if unavailable or nondiagnostic, then an incisional biopsy along the long axis of the extremity is appropriate. Because neoadjuvant radiation or chemotherapy has not been conclusively shown to improve outcome for retroperitoneal WDLPS, preoperative biopsy remains controversial and is not imperative unless complete resection is not considered feasible. Because STS, in general, preferentially metastasizes to the lungs, baseline cross-sectional chest imaging should be obtained. No other routine or special laboratory testing is required. A positron emission tomographic scan can be useful in certain circumstances but should not be used routinely in lieu of CT or MRI.

Clinical evaluation of WDLPS

Because LPS is rare, patients should be considered for referral to a multidisciplinary team with specific STS expertise. All patients need to undergo imaging to determine tumor size, exact location, as well as contiguity or proximity to nearby critical structures. This is best accomplished by computed tomographic (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Both modalities have been shown to accurately predict tumor size and location relative to bone, joints, and neurovascular structures. MRI can more accurately delineate anatomic compartments and muscle involvement. Therefore, it is thought to be better for extremity tumors. CT is preferentially used for central tumors (of the abdomen or retroperitoneum). It also provides very accurate information more rapidly and with less cost than MRI.

Imaging characteristics have been described to differentiate WDLPS from DDLPS. Fat signal intensity is dominant in WDLPS. Conversely, imaging often reveals a heterogeneous nonlipogenic mass for DDLPS. Imaging characteristics aside, a pathologic diagnosis is still necessary before planning treatment. Core needle biopsy is preferred, but, if unavailable or nondiagnostic, then an incisional biopsy along the long axis of the extremity is appropriate. Because neoadjuvant radiation or chemotherapy has not been conclusively shown to improve outcome for retroperitoneal WDLPS, preoperative biopsy remains controversial and is not imperative unless complete resection is not considered feasible. Because STS, in general, preferentially metastasizes to the lungs, baseline cross-sectional chest imaging should be obtained. No other routine or special laboratory testing is required. A positron emission tomographic scan can be useful in certain circumstances but should not be used routinely in lieu of CT or MRI.

Surgical resection

Complete (R0) surgical resection provides the best chance for long-term relapse-free and overall survival. Thus, referring a patient with complex STS to a multidisciplinary team at a high-volume center is warranted. The index surgery offers the best chance for cure, and the feasibility of subsequent operations is often diminished by altered anatomy, scar tissue, or sarcomatosis. For extremity tumors, limb salvage surgery should be the goal. Patients should be referred to STS specialty centers before considering amputation. Amputation is indicated if limb-sparing resection leaves grossly positive margins or a nonfunctional limb. For intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal tumors, complete resection is achieved in only 50% to 95% of patients because of the proximity of vital structures. However, complete resection still remains the most important factor affecting survival. Specialty centers typically advocate a liberal en bloc resection but only with the goal and ability to achieve negative margins. The quality of the surgical resection has been shown to be an independent risk factor for survival. Because of the high rates of local recurrence, retroperitoneal LPS can become a difficult management problem. This topic is discussed at length in other articles in this issue.

By and large, the earlier-mentioned recommendations are for all STSs; they are not specific for WDLPS alone. As previously mentioned, even the diagnosis of LPS represents a heterogeneous population of tumors. Retrospective STS studies include a large percentage of LPS; however, very few patients were specifically subclassified as having WDLPS or DDLPS. Therefore, the varying rates of distant metastases and survival seen in historical LPS series may reflect a failure to place WDLPS and DDLPS into separate subgroups. Regardless, WDLPS typically carries a more favorable prognosis because these patients often only develop locoregional recurrence, not systemic disease. Anaya and colleagues concluded that LPS, particularly WDLPS, is the only histologic STS subtype for which debulking might improve survival and provide palliation because of the low likelihood of metastases. One study specifically addressing this issue found that surgical debulking can be effective for palliating symptoms and may also prolong survival, especially if surgery is the primary resection. This is an obvious contradiction to general STS treatment recommendations but may be appropriate for highly selected cases of WDLPS. Thus, it may be argued that surgery should be considered in almost all patients presenting with a WDLPS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree