Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic, relapsing, highly pruritic, inflammatory skin disease that frequently precedes the development of asthma and/or allergic rhinitis. It is the most common chronic skin disease of young children but can affect patients of any age. The associated sleep disruption, school absenteeism, occupational disability, and emotional stress can have a significant impact on the quality of life of patients and their families. AD may also be associated with significant morbidity, especially when complicated by erythroderma or concomitant infection. The prevalence of AD has continued to increase, affecting more than 10% of children at some point during childhood in most countries. Because wide variations in prevalence both within and between countries inhabited by similar ethnic groups have been documented, environmental factors may be critical in determining disease expression.

I. CLINICAL ASPECTS

A. Natural history. AD typically presents in early childhood with onset before 5 years of age in approximately 90% of patients. Although most children will have milder disease over time, they may continue to have persistent or frequently relapsing dermatitis as adults. Patients with mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin (

FLG) protein (see

Immunopathologic Aspects below) are more likely to have persistent AD.

B. Clinical features. AD has no pathognomonic skin lesion(s) or unique laboratory parameters. Diagnosis is based on the presence of major and associated clinical features (

Table 11-1). The principal features include

pruritus, a chronically relapsing course, typical morphology and distribution of the skin lesions, and a history of atopic disease. The presence of pruritus is critical to the diagnosis of AD, and patients with AD have been shown to have a reduced threshold for pruritus.

1. Acute atopic dermatitis is characterized by intensely pruritic, erythematous papules associated with excoriations, vesiculations, and serous exudate.

2. Subacute atopic dermatitis is characterized by erythematous, excoriated, scaling papules.

3. Chronic atopic dermatitis is characterized by thickened skin with accentuated markings (lichenification) and fibrotic papules. Patients typically have dry skin. Significant differences can be observed between the pH, capacitance, and transepidermal water loss of AD lesions compared with uninvolved skin in the same patients and with the skin of normal controls.

4. During infancy, AD involves primarily the face, scalp, and extensor surfaces of the extremities, although infants can have flexural involvement and the diaper area is typically spared. When involved, it may be secondarily infected with Candida, in which case, the dermatitis does not spare the inguinal folds. In contrast, infragluteal involvement is a common distribution in children.

5. In older patients with long-standing disease, the flexural folds of the extremities are the predominant location of lesions. Localization of AD to the eyelids may be an isolated manifestation but should be differentiated from an allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) (as discussed in Allergic Contact Dermatitis). Chronic rubbing of the skin can result in prurigo nodules.

C. Complicating features

1. Infections. Patients with AD have increased susceptibility to infection or colonization with a variety of microbial organisms.

a. Viral infections include

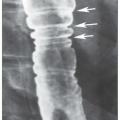

Herpes simplex (HSV) and molluscum contagiosum. Patients can have generalized dissemination of HSV termed eczema herpeticum or Kaposi varicelliform eruption. Corneal involvement is a serious complication and may constitute a medical emergency. A

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viral identification and culture of fluid from freshly unroofed vesicle can be helpful, especially as HSV lesions can become secondarily impetiginized with the viral component undiagnosed. It is worth remembering that molluscum is a contagious disease, and although it often resolves

spontaneously, it can spread and school-aged children need to be treated or their lesions need to be covered.

b. Fungal infections can also cause AD to flare. Malassezia sympodialis is a lipophilic yeast, and IgE antibodies against M. sympodialis have been found predominantly in patients with head and neck dermatitis. The potential importance of M. sympodialis as well as other dermatophyte infections is further supported by the reduction in clinical severity of AD in patients treated with antifungal agents in some studies. Occasionally, resistant cheilitis or fissures may respond to antifungal therapy.

c. Bacterial infections, particularly Staphylococcus aureus, are frequent in patients with AD. S. aureus can be cultured from more than 90% of AD skin lesions. In contrast, only 5% of healthy subjects harbor this organism. S. aureus proteases contribute to skin barrier abnormalities. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has become an increasingly important pathogen in patients with AD. Although recurrent staphylococcal pustulosis can be a significant problem in AD, invasive S. aureus infections are rare and should raise the possibility of an immunodeficiency such as hyper-IgE syndrome.

2. Hand dermatitis. Patients with AD often have nonspecific hand dermatitis. This is frequently irritant in nature and aggravated by repeated wetting, especially in the occupational setting.

3. Ocular problems. Ocular complications associated with AD can lead to significant morbidity. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis is always bilateral, and symptoms include itching, burning, tearing, and copious mucoid discharge. It is frequently associated with eyelid dermatitis and chronic blepharitis and may result in visual impairment from corneal scarring. Keratoconus is a conical deformity of the cornea that may result from persistent rubbing of the eyes in patients with AD and allergic rhinitis. Anterior subcapsular cataracts may develop during adolescence or early adult life.

4. Psychological issues. Patients with AD may have high levels of anxiety and problems dealing with anger and hostility, which can exacerbate the illness. Stress or frustration can precipitate an itch-scratch cycle. In some cases, scratching is associated with secondary gain or with a strong component of habit. In addition, severe disease can have a significant impact on patients’ self-esteem and social interactions.

D. Differential diagnosis. A number of diseases may be confused with AD (

Table 11-2). While patients with hyper-IgE syndrome have eczematous rash and high IgE levels, systemic infections especially staphylococcal or fungal lung disease distinguish them from AD patients. Patients with immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome are males who typically present in infancy with intractable diarrhea. Distribution in the genital and axillary areas, presence of linear lesions, and skin scrapings help to distinguish scabies from AD. While contact dermatitis can be confused with AD, it can also complicate AD especially in patients whose AD appears to flare with therapy (see

Contact Dermatitis below). It is especially important to recognize that in an adult with eczematous dermatitis and no history of childhood

eczema or atopic features, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma needs to be ruled out. Biopsies should be obtained from three separate sites since histology may be similar to AD.

II. IMMUNOPATHOLOGIC ASPECTS

A. Epidermal barrier and genetics. Patients with AD have an abnormal skin barrier with increased transepidermal water loss. A number of genes important for maintaining barrier homeostasis are encoded in the epidermal differentiation complex on chromosome 1q21. Filaggrin protein is involved not only in epidermal barrier integrity but also in epidermal hydration and pH through its amino acid breakdown products that contribute to natural moisturizing factor. Mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG) have been found in approximately 50% of patients with moderate to severe AD and are the strongest risk factors for AD. Patients with FLG mutations have early-onset, severe, and persistent AD and are at greater risk for allergic sensitization and asthma. Buccal swabs or blood can be sent for identification of common FLG mutations (e.g., Advanced Diagnostic Laboratories, National Jewish Health, Denver, CO).

B. Immunohistology. Skin biopsies are rarely needed but may be useful if the diagnosis is in question or the patient does not respond to therapy as expected.

1. Uninvolved skin in AD patients is not normal which has therapeutic implications (see Proactive/Maintenance therapy below). Uninvolved skin is colonized by S. aureus and has increased transepidermal water loss and immune cell abnormalities.

2. Acute lesions are characterized by intercellular edema of the epidermis (spongiosis) and intracellular edema. A sparse lymphocytic infiltrate may be observed in the epidermis, whereas a marked perivenular infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, some monocytes, and rare eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils is seen in the dermis. Mast cells are found in normal numbers in different stages of degranulation.

3. Chronic lesions often demonstrate prominent hyperkeratosis of the epidermis with increased numbers of epidermal Langerhans’ cells and predominantly monocytes/macrophages in the dermal infiltrate. Mast cells are increased in number but are not degranulated. Lymphocytes, in both acute and chronic lesions, are predominantly CD3, CD4, and CD45RO memory T cells that also express CD25 and human leukocyte antigen DR (HLA-DR) indicative of intralesional activation. In addition, almost all of the infiltrating T cells express high levels of the skin homing receptor, cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA), which is a ligand for the vascular adhesion molecule, E-selectin. Langerhans’ cells found in the epidermis and dermis of chronic lesions are potent activators of autologous resting CD4 T cells and have been shown to express high affinity receptors for IgE. The latter appears to play an important role in cutaneous allergen presentation to Th2-type cells. Activated eosinophils are present in significantly greater numbers in chronic as compared to acute lesions. In addition, deposition of eosinophil major basic protein (MBP) can be detected throughout the upper dermis and to a lesser extent deeper in the dermis, especially in involved areas. MBP may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD through its cytotoxic properties and its capacity to induce basophil and mast cell degranulation.

C. Immunoregulatory abnormalities. Immunoregulatory abnormalities during acute AD include an increase in interleukin 4 (IL-4) expression, whereas chronic disease is primarily associated with IL-5 expression. IL-13 expression is also higher in acute lesions, whereas chronic lesions are characterized by increased IL-12 (a potent inducer of interferon g [IFN-g] synthesis) and IFN-g (a Th1-type cytokine) expression. IL-16, a chemoattractant for CD4

+ T cells, is more highly expressed in acute than in chronic skin lesions. In addition, the C-C chemokines, regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), monocyte chemotactic protein 4, and eotaxin are also increased in atopic lesions and likely contribute to the chemotaxis of eosinophils and Th2-type lymphocytes into the skin. Cutaneous T cell-attracting chemokine may play an important role in the preferential attraction of CLA

+ T cells into the skin. IL-31 has been recognized as an important CLA

+ T cell-derived pruritogenic cytokine, and serum IL-31 levels have been shown to correlate with disease activity in AD. Chronic colonization and superinfection by

S. aureus can contribute to pruritus and inflammatory changes in AD since

S. aureus-derived toxins rapidly

induce IL-31 in the skin of AD patients. Keratinocyte-derived thymic stromal lymphopoietin, a key regulator for allergic inflammation, is overly expressed in the skin of AD patients and exerts effects on a number of key cells including T cells, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils leading to a Th2-polarized milieu.

III. IMMUNOLOGIC TRIGGERS

A. Foods. Double-blinded, placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) have demonstrated that food allergens can cause AD exacerbations in a subset of patients, primarily young children. Approximately one-third of children with chronic moderate to severe AD may have associated IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity. Seven foods (milk, egg, peanut, soy, wheat, fish, and tree nuts) account for nearly 90% of the positive DBPCFC. These data reaffirm the need to consider the role of food allergens in children with AD who do not respond readily to conventional therapy. Notably, elimination of proven food allergens results in amelioration of skin disease and a decrease in spontaneous basophil histamine release.

B. Aeroallergens. The evidence supporting a role for aeroallergens in AD includes the finding of both allergen-specific IgE antibodies and allergen-specific T cells. Exacerbation of AD can occur with exposure to allergens such as house dust mites. Direct contact with inhalant allergens can also result in eczematous skin eruptions. Dust mite proteases contribute to skin barrier breakdown. Environmental control measures have resulted in clinical improvement of AD.

C. Microbes. AD patients are frequently colonized by S. aureus that produce toxins with superantigenic properties, causing significant activation of proinflammatory cells and cytokines. In addition, patients make specific IgE antibodies directed against the staphylococcal toxins found on their skin. S. aureus-specific IgE has been shown to correlate with clinical severity of AD and may contribute to persistent inflammation or exacerbations of AD.