Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a common disease, with a prevalence as high as 1 in 400 women and 1 in 1000 men, and most are asymptomatic. Patients with PHPT have hypercalcemia with inappropriately normal levels of parathyroid hormone. Parathyroidectomy is the only curative therapy, and the procedure has become more common and more safe. Among asymptomatic patients, parathyroidectomy halts the progression of disease, improves quality of life, and may decrease risk of fracture and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, surgery should be considered in all patients with asymptomatic PHPT who have minimal perioperative risk and sufficient life expectancy, regardless of chronologic age.

Key points

- •

In most cases, primary hyperparathyroidism can be diagnosed by measuring serum calcium and parathyroid hormone.

- •

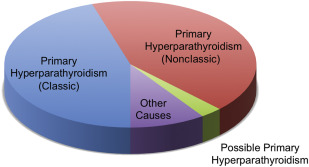

Nearly half of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism have a “nonclassic” presentation, with hypercalcemia and inappropriately normal parathyroid hormone levels.

- •

Parathyroidectomy has become a more commonplace and safe procedure, but many patients, especially elderly patients, are not appropriately referred for surgical consultation.

Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a disease caused by the excess production of parathyroid hormone (PTH), resulting in the dysregulation of calcium metabolism. The current estimated prevalence of PHPT is as high as 1 in every 400 women, and 1 in 1000 men. Symptoms caused by hypercalcemia and elevated PTH levels manifest insidiously over an extended period of time; most patients with PHPT are asymptomatic, with only a small fraction exhibiting classic signs and symptoms. Patients with asymptomatic disease were largely undiagnosed until the advent of the multichannel autoanalyzer in the 1970s, which subsequently led to the adoption of routine serum calcium measurements. Detection of hypercalcemia on routine serum calcium screening has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of PHPT: from 1995 to 2010, the incidence of PHPT tripled. This article addresses the diagnosis and surgical management of asymptomatic PHPT.

Introduction

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is a disease caused by the excess production of parathyroid hormone (PTH), resulting in the dysregulation of calcium metabolism. The current estimated prevalence of PHPT is as high as 1 in every 400 women, and 1 in 1000 men. Symptoms caused by hypercalcemia and elevated PTH levels manifest insidiously over an extended period of time; most patients with PHPT are asymptomatic, with only a small fraction exhibiting classic signs and symptoms. Patients with asymptomatic disease were largely undiagnosed until the advent of the multichannel autoanalyzer in the 1970s, which subsequently led to the adoption of routine serum calcium measurements. Detection of hypercalcemia on routine serum calcium screening has greatly facilitated the diagnosis of PHPT: from 1995 to 2010, the incidence of PHPT tripled. This article addresses the diagnosis and surgical management of asymptomatic PHPT.

Biochemical diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism

Our standard biochemical panel for the initial workup of suspected PHPT is shown in Box 1 . Most ambulatory patients have normal serum phosphorus, creatinine, and albumin. Hence, the diagnosis can be determined by serum calcium and serum PTH in most cases. We routinely measure the serum 25-hydroxy (25-OH) vitamin D level to clarify the diagnosis in borderline cases, and to help differentiate between primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism.

Routine tests

Serum calcium

Parathyroid hormone

Serum phosphorus

Serum creatinine

Serum albumin

Optional tests

Ionized calcium (hypoalbuminemic patients, borderline diagnoses)

25-OH vitamin D (nonclassic presentation or suspected vitamin D deficiency)

Urinary calcium excretion (suggestive family history for FHH)

Abbreviation: FHH, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia.

Calcium

Suspicion of asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism typically begins with incidental detection of elevated serum calcium. A single elevation of the serum calcium is frequently spurious. Therefore, repeat testing of the serum calcium is recommended before proceeding further in the diagnostic workup of PHPT. Because 40% to 45% of serum calcium is protein-bound, total serum calcium should be corrected for serum albumin. Corrected serum calcium is calculated by the following: measured total serum calcium (mg/dL) + 0.8 (4.0 – measured serum albumin [g/dL]). Per the recent 2013 guidelines established by the Fourth International Workshop on the Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism, total serum calcium should be used to establish the diagnosis and not ionized calcium, because ionized calcium testing is not widely available.

Ionized calcium directly measures the bioactive (free) fraction of serum calcium, which more accurately reflects patients’ true calcium status than albumin-corrected total calcium, particularly for patients with hyperparathyroidism. Among patients with histologically confirmed PHPT, up to 24% have elevated ionized calcium levels despite normal total calcium levels. Additionally, ionized calcium may be informative in hypoalbuminemic patients (ie, patients with cirrhosis or nephrotic syndrome) with suspected PHPT. However, we have noted greater intra-assay variability when measuring ionized calcium compared with total calcium, which may be attributed to the pH-dependence of ionized calcium.

Parathyroid Hormone

Excess production of PTH can be easily determined by measuring serum PTH. Serum PTH should be interpreted in the context of serum calcium. In patients with hypercalcemia or calcium levels near the upper limit of the reference range, an elevated serum PTH is diagnostic of PHPT. However, a normal PTH level does not rule out PHPT; up to half of patients with PHPT have hypercalcemia with inappropriately normal levels of PTH.

PTH assay has undergone evolution over the past 53 years. First-generation PTH assays are obsolete, now replaced by second-generation and third-generation assays. The second-generation PTH assays cross-react with large degradation products of PTH, whereas third-generation assays are more specific for biologically active PTH. Nonetheless, the diagnostic sensitivity of second-generation and third-generation PTH assays are similar for PHPT. In patients with chronic kidney disease, impaired clearance of degradation products of PTH will result in much higher readings with second-generation assays compared with third-generation assays. Third-generation PTH assays also have greater utility as intraoperative PTH assays. Today, most commercial PTH assays are second-generation assays, but also include third-generation assays. Significant variability has been demonstrated between commercially available assays, even between tests of the same generation, so it is important to remain consistent and to interpret results using test-specific reference ranges.

Hypercalcemia with Inappropriately Normal Parathyroid Hormone: Nonclassic Primary Hyperparathyroidism

In some patients with PHPT, serum PTH is not elevated above the 95% reference range. An inappropriately normal (nonsuppressed) PTH level despite hypercalcemia is still indicative of disrupted negative feedback, and confirms the diagnosis of nonclassic PHPT. Nonclassic PHPT simply refers to PHPT that presents with elevated serum calcium but inappropriately normal PTH (PTH 21–65 pg/mL). In a study of 3.5 million patients within a vertically integrated health care organization, we found that the number of patients with nonclassic PHPT nearly equaled the number with classic PHPT ( Fig. 1 ). Patients with nonclassic PHPT were not regularly monitored, infrequently underwent bone densitometry measurement, and were rarely referred for surgery, reflecting missed or delayed recognition of the diagnosis. In our practice, we have noted considerable confusion on the part of general practitioners and even endocrinologists with regard to establishing the diagnosis nonclassic PHPT.

Vitamin D

Although vitamin D levels are not required to establish the diagnosis of PHPT in patients with “classic” PHPT, serum 25-OH vitamin D levels can clarify the diagnosis in challenging or borderline cases. Because adequate levels of vitamin D can suppress PTH secretion, the Endocrine Society and Institute of Medicine both agree that the reference range of PTH values for vitamin D–replete patients should be lower than for patients who are vitamin D deficient. The strict definition of “vitamin D replete” is controversial, as the Institute of Medicine and 2013 International Workshop both recommend a threshold of 50 nmol/L to be considered “vitamin D replete,” whereas the Endocrine Society has recommended a more stringent threshold of 75 nmol/L. Reference ranges for PTH for vitamin D replete versus vitamin D deficient have not been well characterized, and remain an area for future research. Nonetheless, clinicians should have a higher degree of suspicion for PHPT in hypercalcemic patients with inappropriately normal serum PTH who are vitamin D replete.

Vitamin D measurements are also important in patients who have elevated serum PTH but normal or high-normal serum calcium to rule out secondary hyperparathyroidism due to vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D deficiency is quite commonplace, and may account for normal or high-normal PTH values in patients with PHPT. The estimated prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in adults is as high as 41.6%, and more common among individuals with pigmented skin, obesity, or poor milk intake. Among internal medicine housestaff, 51.4% of residents were found to be vitamin D deficient at some point over the course of a year, more so during winter months. Significant vitamin D deficiency can cause a physiologic increase in PTH secretion, mimicking incipient (normocalcemic) PHPT. PHPT and secondary hyperparathyroidism due to vitamin D deficiency can be distinguished by measuring serum 25-OH vitamin D.

Patients who have undergone malabsorptive bariatric surgery (ie, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch) frequently experience postoperative fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, including vitamin D deficiency. This does not include purely restrictive bariatric procedures, such as vertical banded gastroplasty or sleeve gastrectomy. Vitamin D deficiency and elevated PTH following malabsorptive bariatric surgery are not only long-term, but may also worsen over time. Furthermore, patients who have undergone bariatric surgery have been shown to have impaired calcium absorption despite normal 25-OH vitamin D levels. In our practice, patients who have undergone malabsorptive bariatric surgery are assumed to have secondary hyperparathyroidism due to vitamin D deficiency unless hypercalcemia has been confirmed with laboratory testing.

Urinary Calcium Excretion

Urinary calcium excretion can help distinguish PHPT from familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, where patients also experience hypercalcemia and have elevated levels of serum PTH. However, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHH) is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 78,000 in the general population. Thus, we only obtain urinary calcium excretion in patients with a suggestive family history. Patients with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia will have 24-hour urine calcium excretion less than 100 mg. Of note, patients with vitamin D deficiency superimposed on PHPT can have low 24-hour urinary calcium excretion, although generally closer to low-normal levels of approximately 200 mg.

Considerations for differential diagnosis

Familial Hypocalciuric Hypercalcemia

FHH is a disorder caused by a mutation in the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) found in a number of organs, including the parathyroid glands and kidneys. The parathyroid glands are unable to sense changes in serum calcium, and do not inhibit secretion of PTH in response to elevated serum calcium. More importantly, CaSR regulates renal excretion of calcium; the CaSR mutation in patients with FHH inhibits renal calcium excretion, leading to hypercalcemia. Patients with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia have elevated serum calcium, and up to 20% also have mild elevations in serum PTH, mimicking PHPT. As stated previously, the main distinguishing feature of FHH is low urinary calcium excretion, whereas urinary calcium excretion is normal or high in PHPT. Patients with FHH also typically exhibit hypercalcemia in childhood, and do not show signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia.

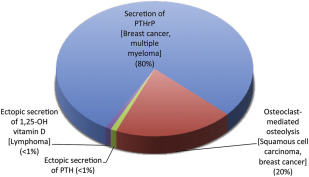

Malignancy

Malignancy is the second most common cause of hypercalcemia after PHPT, and the most common cause of hypercalcemia among inpatients. Hypercalcemia of malignancy can occur via a number of different mechanisms: humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy caused by secretion of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), osteoclast-mediated osteolysis typically caused by bony metastatic disease, or, in rare cases, ectopic secretion of 1,25-OH vitamin D or PTH ( Fig. 2 ). In most cases, hypercalcemia of malignancy occurs after malignancy is clinically evident. Hypercalcemia of malignancy should lead to suppression of endogenous PTH, so it can easily be distinguished from PHPT by measuring serum PTH and/or serum PTHrP. In rare cases, there can be concomitant hyperparathyroidism where PTH will be elevated as well as parathyroid-related peptide.

Thiazides

Thiazide diuretics act on the distal convoluted tubule of the kidney, reducing calcium excretion, and can cause a mild hypercalcemia. Patients with mild hypercalcemia with normal or high-normal PTH should discontinue thiazide medications and have calcium and PTH reassessed after 3 months. Elevated serum calcium despite withdrawal of thiazides supports the diagnosis of PHPT.

Lithium

The exact mechanism of action of lithium on calcium metabolism is unknown, although it is hypothesized to act downstream of the calcium-sensing receptor. Lithium appears to interfere with CaSR activity in the parathyroid gland and kidneys, leading to elevated PTH levels, hypercalcemia, and hypocalciuria. If possible, patients with hypercalcemia should be switched to an alternative medication and have their calcium retested.

Indications, risks, and benefits of parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism

Surgery is the only curative therapy for PHPT, and is clearly indicated in all symptomatic patients. Even for asymptomatic patients, parathyroidectomy halts, or even reverses, the classic negative effects of this disease: parathyroidectomy decreases the risk of nephrolithiasis and improves bone mineral density (BMD). There is also additional evidence that parathyroidectomy may also improve quality of life in “asymptomatic” patients, possibly by alleviating nonspecific or atypical symptoms. Finally, there may still be unrecognized effects of asymptomatic PHPT: a large population-based study examining 2299 patients with untreated asymptomatic PHPT found an increased risk of nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.

In the past decade, the safety of parathyroidectomy has improved: the overall complication rate following 17,082 patients who underwent parathyroidectomy fell from 8.7% to 3.8% from 1999 to 2008. The most common surgical complication was hypocalcemia, and vocal cord paresis accounts for only 3.7% of all complications.

The indications for surgery in asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism have been an area of intense research and debate. The first official guidelines for surgery for asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism were established in 1990, at a consensus conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. These guidelines have undergone several revisions by conferences convened in 2002 and 2008, and most recently during the 2013 Fourth International Workshop on the Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism. The surgical criteria for parathyroidectomy are listed, by year of consensus statement, in Table 1 . Analyses of the individual components of surgical criteria for PHPT are as follows.

| 1990 | 2002 | 2009 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum calcium | 1–1.6 mg/dL above reference range | 1.0 mg/dL above reference range | 1.0 mg/dL above reference range | 1.0 mg/dL above reference range |

| Skeletal criteria | DXA: Z-score <−2 | DXA: T-score <−2.5 at any site | DXA: T-score <−2.5 at any site | DXA: T-score <−2.5 at lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck, or distal one-third radius |

| Vertebral fracture by spinal imaging or vertebral fracture assessment | ||||

| Renal criteria | eGFR reduction >30% from expected | eGFR reduction >30% from expected | eGFR <60 mL/min | Creatinine clearance <60 mL/min |

| 24-h urine calcium excretion >400 mg | 24-h urine calcium excretion >400 mg | 24-h urine calcium excretion >400 mg AND High-risk urinary biochemical stone risk analysis | ||

| Nephrocalcinosis or nephrolithiasis | ||||

| Age | Age <50 | Age <50 | Age <50 | Age <50 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree