INTRODUCTION

Nausea and vomiting are common and distressing symptoms in patients with cancer, occurring in up to 70% of patients with advanced disease and in at least 40% during the last 6 weeks of life (

1,

2,

3). These symptoms rarely occur in isolation and cause substantial psychological distress for both patients and families. Inadequately treated nausea and vomiting may lead to serious complications, including dehydration, electrolyte disturbances, anorexia, weight loss, and psychological distress, which may exacerbate patient and family concerns about starvation and progressive decline.

Nausea and vomiting, though commonly clustered together, are separate entities. Nausea is a subjective phenomenon often described as the unpleasant sensation of the need to vomit, of feeling “queasy,” or “sick in your stomach.” It is frequently associated with autonomic symptoms such as cold sweats, pallor, diarrhea, and tachycardia (

4). Vomiting is a protective reflex triggered by chemical or physical stimuli, which leads to the expulsion of gastric contents through the mouth and, sometimes, the nose. The vomiting act has two phases, retching and expulsion. Retching is the strong involuntary effort to vomit without bringing anything up. It involves a deep inspiration against a closed glottis. The act of vomiting involves contraction of the abdominal muscles, leading to a pressure differential between the abdominal and thoracic cavities. The stomach and gastric contents are pushed toward the thoracic cavity. The expulsion phase occurs when the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes and the gastric contents are expelled through the mouth. Vomiting occurs as a result of complex muscular and neurophysiologic interactions, which provide the foundation for current pathophysiology-based treatment recommendations. The neural pathways that mediate nausea are not known. The anticipated level of success in controlling vomiting as opposed to nausea may reflect the limited understanding of the pathophysiologic basis of nausea.

ETIOLOGY AND ASSESSMENT OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING

A pathophysiology-based treatment approach is generally recommended for the control of nausea and vomiting (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12). The effectiveness of this approach relies on the ability to accurately identify the cause of the symptoms. Etiologybased guidelines for the management of nausea and vomiting in hospice patients are moderately effective. In one recent investigation, physicians expressed confidence in their ability to identify a clear etiology of nausea and vomiting 75% of the time (

8). As many as a quarter of patients were felt to have multiple causes to explain their symptoms. The most common cause of nausea and vomiting was delayed gastric emptying (44%), followed by “chemical” causes (metabolic, medications, and infection) (33%). Using etiology-based guidelines, nausea was controlled for 44% of patients at 48 hours and for 56% at 1 week. Vomiting was more effectively controlled: 69% of patients had control at 48 hours and 89% at 1 week. These results are consistent with those previously reported (

11,

12). Careful patient assessment, identification of the source of nausea and vomiting when possible, use of pathophysiology-based guidelines, and clinical judgment underlie effective management of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced illness (

5,

8,

9,

10).

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Careful clinical evaluation is the first step to ascertain the etiology of nausea and vomiting. Initial assessment begins with a thorough history and physical examination, including a review of recent and current medication use (including supplements and over-the-counter medications), comorbid conditions, associated signs and symptoms, history of the frequency and acuity of nausea and vomiting, the impact of oral intake, and changes in bowel habits. This assessment can focus the diagnostic evaluation and limit the need for biochemical evaluation or radiologic investigations. A simple pneumonic for recalling the potential causes of nausea and vomiting are the 12 Ms.

Table 13.1 lists the 12 Ms of nausea and vomiting, many of which can be excluded on the basis of history and physical examination alone.

In patients with advanced cancer, the onset of any new symptom may raise patient and family concern of progressive cancer. Progressive metastatic disease may cause nausea and vomiting based on multiple etiologies. New or recurrent brain metastases may present with nausea and vomiting. Increased intracranial pressure is one of the few causes of vomiting without nausea, classically described as projectile vomiting and associated with an early morning headache. A patient with hydrocephalus secondary to carcinomatous meningitis may present with intractable nausea and vomiting in association with neck stiffness, with or without other signs of central nervous system (CNS) disease, such as diplopia. Nausea and vomiting from CNS metastases is generally not

effected by oral intake and has no effect on bowel pattern. Intra-abdominal metastases leading to partial or complete bowel obstruction often presents with continuous nausea, briefly relieved by acute large volume emesis (if the obstruction is in the proximal small bowel). The nausea and vomiting of bowel obstruction is associated with difficulty eating both solids and liquids, and the absence of flatus or bowel movements if the obstruction is complete. These symptoms may be accompanied by colicky abdominal pain. The clinical presentation paints a picture of the etiology of the symptoms.

Table 13.2 compares and contrasts the clinical presentation of some of the most common causes of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer.

Clinical assessment includes a thorough description of the characteristics of the symptoms. Does the nausea occur primarily in the morning or after eating? Is the nausea precipitated by movement? Did it begin after medication changes? A change in dose? Initiation of new over-the-counter medications or supplements? Are the symptoms chronic or acute? Nausea, a subjective symptom, is not always clearly defined by patients. A patient report of anorexia or dyspepsia may represent low-grade chronic nausea. Are the symptoms constant or intermittent? Are there interventions that have improved the symptoms? Does eating make the symptoms worse? Gastroparesis is associated with significant difficulty with advancing solids, particularly fiber-rich foods, out of the stomach. Are there associated symptoms of abdominal distention and early satiety as might be expected in a patient with increasing intra-abdominal cancer or progressive ascites? Does early satiety occur without significant abdominal distension, which might suggest gastric stasis? Has the patient’s bowel pattern changed? Constipation is a potential cause of nausea, especially in patients with decreased ambulation and for those receiving opioids. The frequency and consistency of bowel movements is essential historical information. The presence of delerium raises the suspicion for a metabolic cause of nausea. Comorbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, systemic infection, hypothyroidism, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or cardiac disease, may lead to nausea and vomiting. A list of current medications may quickly clarify the etiology of a patient’s nausea and vomiting. A recent prescription for opioids and rapid titration of the opioid are frequent causes of nausea and vomiting. In the setting of advanced cancer, opioids are the most common cause of medication-related nausea and vomiting, but there are many medications that need to be considered (

13) (see

Table 13.3).

Physical examination provides diagnostic information and an assessment of the overall status of the patient. The presence of marked muscle wasting, poor performance status, and other hallmarks of very advanced illness may temper a decision for diagnostic studies. Physical examination may identify papilledema or cranial nerve abnormalities that suggest elevated intracranial pressure or meningeal disease, respectively. Examination of the abdomen may identify a succussion splash on auscultation of the epigastric area when the patient moves, suggesting gastroparesis. The presence of

abdominal distention and absent bowel sounds in the setting of vomiting and constipation are highly suggestive of bowel obstruction. Rectal examination can rule out constipation as a cause of nausea. Hepatomegaly and/or ascites are useful clues to explain symptoms of early satiety due to gastric stasis or delayed gastric emptying.

Depending on the goals of care, directed by discussion with the patient and family, a biochemical and radiologic evaluation may be advised. Simple laboratory tests will identify hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, pancreatitis, and liver or renal failure as potential causes of nausea and vomiting. When the clinical picture suggests bowel obstruction, an abdominal x-ray is diagnostic. Imaging of the brain or abdomen is only appropriate, however, if the information will change the treatment plan. For a patient with otherwise well-controlled cancer, and/or a survival measured in months, more extensive evaluation, including radiologic studies (computed tomography of the abdomen or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain) and endoscopy, is frequently recommended.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF NAUSEA AND VOMITING

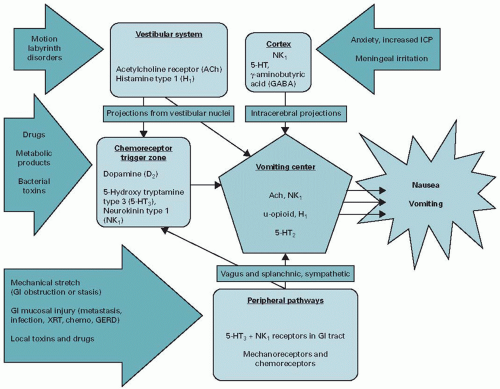

Once the etiology of nausea and vomiting is ascertained, treatment is directed by the pathway and neurotransmitters triggered by a particular cause. The pathways and neurotransmitters involved in nausea and vomiting are summarized in

Figure 13.1 (

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19). The vomiting center is the

final common pathway, likely mediated through substance P, for the generation of the complex patterned response that results in the vomiting reflex. There are four major pathways that provide input to the vomiting center:

The chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), a receptor-rich area of the floor of the fourth ventricle, has numerous dopamine (D2), serotonin (hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor [5-HT3] and hydroxytryptamine type 4 receptor [5-HT4]), opioid, acetylcholine, and substance P receptors. It is a circumventricular organ, lying outside of the blood-brain barrier, allowing for stimulation by toxins from the blood and cerebral spinal fluid.

The vestibular system is rich in histamine (H1) and muscarinic receptors. Its stimulation of the vomiting center is mediated through labyrinthine inputs via cranial nerve VIII, the vestibulocochlear nerve, which plays a major role in motion sickness.

The vagal and enteric nervous system transmits information to the brain regarding the state of the gastrointestinal system. The vagal efferent neurons are located in close proximity to the enterochromaffin cells of the small intestine, the body’s primary storage site for serotonin. Distention of the gut or irritation of the mucosal surface leads to activation of 5-HT3 receptors, stimulation of vagal afferents, and an emetic response.

The cortex is thought to mediate nausea and vomiting from meningeal irritation, increased intracranial pressure, psychiatric disorders, and unpleasant inputs from the five senses (for example, foul odors).

TREATMENT—NON-PHARMACOLOGIC

Treatment of any symptom can be divided into non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches. Common sense recommendations for patients with nausea and vomiting include a recommendation for frequent small meals, particularly if early satiety plays a role in the patient’s symptoms. Avoidance of hot food may be of benefit as it has a stronger aroma than either cold or room temperature foods. Psychiatric techniques to promote relaxation and provide distraction or positive imagery may offer relief from nausea and vomiting, especially for patients with a psychological component to their symptoms (

20,

21). While medical hypnosis may significantly reduce anticipatory chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, there are inadequate data to recommend it in patients with advanced cancer (

22,

23). Both acupuncture and acupressure have been purported to be of benefit (

23). A meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of acupuncture and acupressure for control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting concluded that there is some beneficial effect of acupuncture-point stimulation on acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (

23,

24). A Cochrane Library review of 40 trials assessing the use of acupuncture/acupressure for non-chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting, mostly comprised studies of healthy adults undergoing elective surgery with general anesthesia, evaluated stimulation of the P6 point (a point on the wrist; it’s stimulation prevents nausea and vomiting) versus either a sham or pharmacologic antiemetic treatment (

25). Acupressure of the P6 point significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting compared with the sham procedure. There are no reliable data demonstrating the relative efficacy of pharmacologic interventions and acupuncture/acupressure for treatment of nausea and vomiting (

25). In the palliative care setting, one very small study suggested that acupressure may reduce nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced illness (

26).