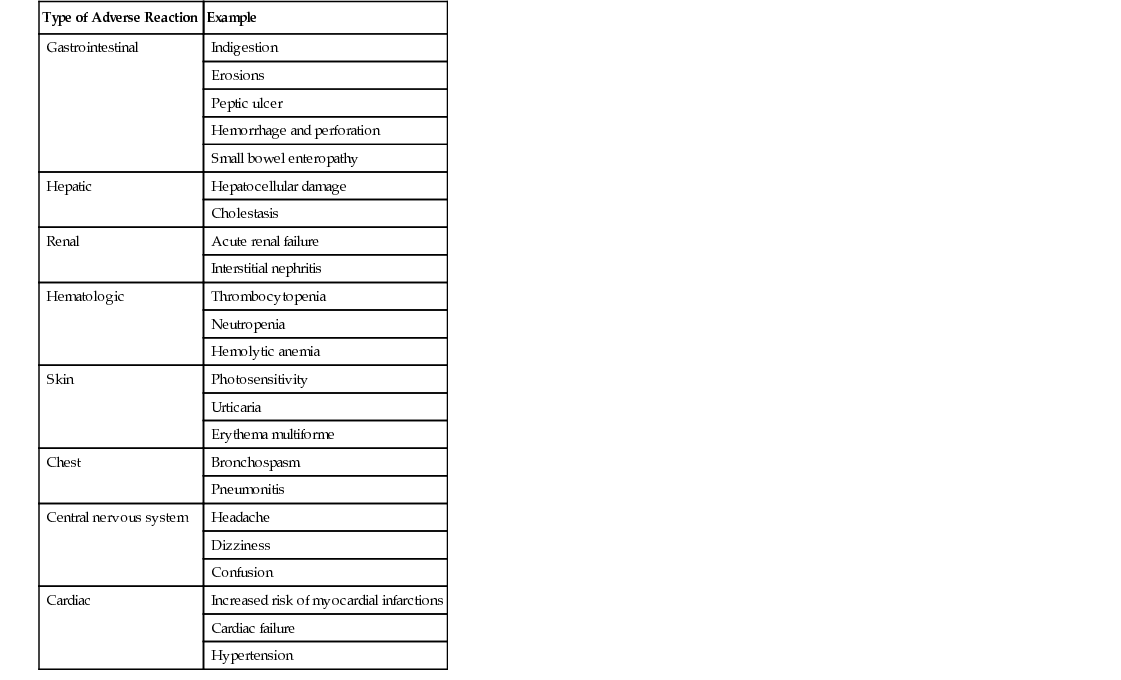

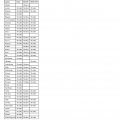

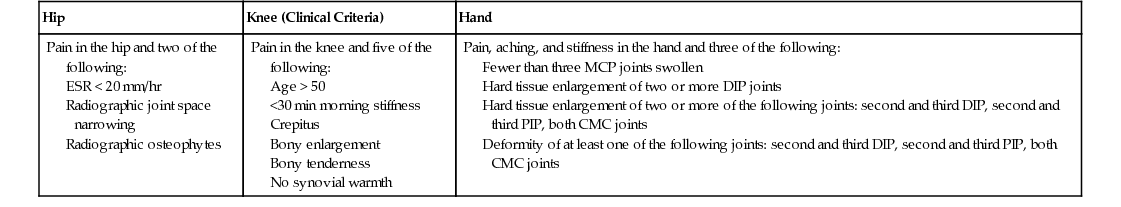

Preeti Nair, Jiuan Ting, Helen I. Keen, Philip G. Conaghan Rheumatologic diseases are among the most common causes of pain and disability in older people.1 The prevalence continues to rise with age even in the older adult population, such that by the age of 85 years, the lifetime prevalence of arthritis diagnosed by a general practitioner in the United Kingdom is 65%.2 Although some conditions are seen in adults of all ages, the clinical presentation and treatment goals will differ in frail older adults with complex comorbidities.3 It is important to keep in mind the impact of musculoskeletal pain on the individual. Pain is associated with muscle loss, functional limitations, fatigue, sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and poor quality of life, especially in those older than 75.4 Although nearly all rheumatic conditions afflict older adults, some are more common in this age group, especially osteoarthritis (OA) and tendon disorders. The most common rheumatic condition in the older adult population are summarized in Table 69-1. However, people commonly present with more than one rheumatic condition for example, with combinations of mechanical lower back pain, knee OA, and shoulder tendonitis. A survey of more than 16,000 people older than 55 years reported that the median number of painful joints was four.5 TABLE 69-1 Common Rheumatic Conditions in Older Adults Because there are more than 100 different musculoskeletal conditions, history and examination findings are critical for establishing a “mechanical” or “inflammatory” diagnostic label, thereby guiding the need (or often not) for subsequent investigations. The duration of early morning stiffness is useful: typically, an inflammatory arthritis is associated with more than 60 minutes of morning stiffness, with a clear difference between this morning stiffness and the rest of the day. When people report all-day stiffness, this is unlikely to be true morning stiffness. Typically, an OA joint will produce less than 10 minutes of morning stiffness and is usually associated with disuse stiffness after a period of the mobilization such as sitting. It is not unusual for tendonitis to give 30 minutes of morning stiffness. Mechanical joint pains are usually worse with prolonged usage or weight bearing. The timing of onset of arthritis may be useful in diagnosis: a rapidly painful and swollen joint would raise the question of acute gout, pseudogout, or a septic arthritis. Another important part of history taking is looking for diseases that may be associated with an inflammatory arthritis, such as psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, or recent diarrheal infections. There may also be features that suggest that the presenting symptoms are part of a broader connective tissue disease, such as photosensitivity or Raynaud phenomenon. A family history may be useful, although often people don’t know what sort of arthritis their family member(s) had. Although uncommon, it is always important to check for “red flag” signs of potential malignancies, especially predominant night pain and associated weight loss or night sweats. Clinical examination findings are often difficult to interpret, even for experienced clinicians. Modern imaging modalities have highlighted the inaccuracies of clinical examination. The presence of soft-tissue joint swelling or synovitis is not diagnostic in itself of an inflammatory arthritis, as synovitis is common in OA. However, the presence of symmetrical synovitis in multiple small hand joints should raise suspicion of inflammatory arthritis. Bony swelling generally indicates OA. Osteoarthritis refers to a clinical syndrome with a variety of causes and outcomes that often differ by joint, but with common pathologic features in the established condition.6 It is the most common joint problem, with age being the strongest risk factor, and for that reason it is the main focus of this chapter.7 The OA process is difficult to define in a succinct phrase because of its complex causes and risk factors and because it impacts patients differently. Definitions traditionally focus on features such as pathology (using radiographic structure), clinical features, or a combination of these. As yet there are no validated diagnostic criteria, although the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has devised classification criteria that emphasize age, symptoms (including inactivity stiffness), and signs (including crepitus and swelling)8 (Table 69-2). TABLE 69-2 American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Osteoarthritis Pain in the hip and two of the following: Pain in the knee and five of the following: Pain, aching, and stiffness in the hand and three of the following: Symptomatic OA is more common in women than men, especially in older adults, with a rising prevalence in the Western world. Increases are largely attributable to the aging population11 and obesity; nearly 1 in 2 people have knee OA by the age of 85 years.12 Other factors associated with OA initiation include obesity, genes, and epigenetics as well as joint injury or joint overuse (e.g., in certain occupations or elite athletes). The various risk factors, however, may operate differently on individual joints at varying stages of the OA process, depending on personal mechanical factors such as weight and muscle strength and perhaps on the different metabolic and restorative properties of the joint at different ages13 (Table 69-3). TABLE 69-3 Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis Repetitive ergonomic and biomechanical demands may create joint stresses leading to OA Hemiparesis associated with reduction of expression of OA in the affected limb and overexpression in the remaining functional limb35 Chopstick use associated with OA of the IP joint of the thumb, second and third MCP, and PIP joints27 The age association is strongest in women: possibly a hormonal influence Hand OA has a peak incidence in menopausal women14 Controversial Hand OA has a peak in menopausal women; however, the Chingford and Framingham studies suggested estrogen has protective effect37,40 Obesity is strongly associated with the incidence of knee OA41 Varus deformity of the knee is associated with progressive OA, as is varus/valgus ligamentous instability at the knee joint Developmental problems leading to altered joint biomechanics such as congenital dysplasias Despite its varied causal factors, OA is characterized by a remarkably uniform pathologic process of aberrant joint repair ending in joint failure.7 The process involves decompensation of reparative mechanisms and an imbalance between synthesis and degradation of hyaline cartilage and subchondral bone,7 resulting in changes affecting the entire joint, including these tissues and the synovium.14 It is important to note that whereas the historical focus on OA was as a disorder of cartilage, it is now recognized that clinical OA refers to a process involving the whole joint organ, with involvement of all elements of the joint. Cartilage is a metabolically active tissue, with abundant extracellular matrix (mainly type 2 collagen and proteoglycans) regulated by chondrocytes that, when activated, produce inflammatory cytokines and matrix-degrading enzymes.15 Chondrocytes also interact with the innate immune system through toll-like receptor expression, activated by molecules that are found in the setting of damage but also by the crystals associated with later-stage OA.15 It is also hypothesized that a metabolic shift toward catabolism may occur in chondrocytes, as age is associated with increasing levels of advanced glycation end products (which increase oxidative damage) and chondrocytes are known to express receptors for these products.15 The importance of the subchondral bone in OA is increasingly being recognized.16 The active osteocytes in subchondral bone undertake homeostatic remodeling. It has been demonstrated that osteocytes express inflammatory cytokines and proteases in response to mechanical stress.17 In these areas of stress, where bone is lying under damaged cartilage, the homeostasis may alter such that bone formation predominates, resulting in thickened, stiffened bone. In addition, new blood vessels and nerves infiltrate damaged cartilage, to facilitate new bone formation within the cartilage, and create osteophytes, further contributing to cartilage thinning.18 This process is considered an aberrant healing process; the extension of articular surfaces may allow redistribution of abnormal joint forces.19 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has demonstrated the presence of bone marrow lesions, areas of fibrosis, necrosis, and remodeled trabecular bone in about 50% of people with symptomatic OA. These lesions are associated with pain and subsequent compartment-specific cartilage loss.20 Synovial inflammation has also been found to be common in imaging studies of OA,21,22 thought to be reactive to bone and cartilage pathology. Cartilage breakdown products released into the synovial fluid infiltrate the synovium and are irritants23 resulting in inflammation. This results in the production of inflammatory cytokines and cartilage degradation enzymes, which diffuse into the cartilage stimulating chondrocyte release of proinflammatory cytokines, inhibiting collagen and proteoglycan synthesis,23 and generally further perpetuating the destructive process.16 Synovitis is associated with structural progression of the disease24 and joint replacement.25 OA may be conceptualized as the result of abnormal forces on normal joint tissues, or normal forces on an abnormal joint, or the interplay of both. These interactions are likely to involve host factors (genetics, age, gender) and environmental factors (biomechanics, trauma). It is also possible that some risk factors have not yet been identified. It has been proposed that local biomechanical factors (obesity, joint injury, muscle weakness) initiate damage in OA in joints that are vulnerable because of systemic factors (genetics, age, gender).7 In OA of the hand, for example, studies have demonstrated handedness and mechanical loading as risk factors, whereas other studies (often focusing on radiographic changes and not symptoms) have found symmetry to be so prevalent that intrinsic factors are likely to be responsible.26–30 The Hizen-Oshima study29 found both handedness and symmetry to be associated with OA. Although symmetry was the predominant pattern of involvement in this cohort, the prevalence of index distal interphalangeal joint, thumb interphalangeal joint, and thumb metacarpophalangeal joint involvement was significantly higher in the dominant hand. Almost any joint may be affected with OA, but most commonly, OA involves the knees, feet, hands (base of thumb and fingers), and hips. Changes typical of OA are very commonly also seen in the lumbar and cervical spine, but because back pain often involves varying pathologies (including disc degeneration, nerve root compression, and crush fractures, as well as OA changes), the term peripheral joint OA is commonly used to separate the OA syndrome in these joints from spinal disease. There is no widely accepted classification for clinical OA, and it is often described by the distribution of joints involved. For example, disease may be limited to a single joint, such as the knee, or it may be more generalized. Whether subgroups represent specific and pathologically distinct subgroups is uncertain. Currently, generalized OA is considered to be hand OA plus involvement at other sites31 (generally involvement of three or more joints); however, Kellgren originally coined the term primary generalized OA to describe a subset of people with widespread disease (particularly involving the hands and weight-bearing joints such as the knee) on observing a bimodal frequency of joint distribution in his cohort.28 Dieppe and colleagues have demonstrated a strong positive relationship between age and number of joints affected in individuals with OA. This is likely to be due to a bias of time, meaning that older people recruit new sites with age, and in this study, no distinct subgroups of joint involvement were identified.32 Inflammatory OA is a poorly defined term that refers to a subgroup with a marked inflammatory process affecting hand joints and is sometimes used interchangeably with the term erosive OA. Crystal deposition disease is common in advanced OA, often detected clinically as radiographic chondrocalcinosis, and this may cause acute-on-chronic flares of joint pain associated with highly elevated inflammatory markers. A rare subgroup is that characterized by a rapidly destructive process affecting a large joint with radiographic changes that may mimic septic arthritis, sometimes referred to as rapidly progressive OA.43 Typically, this presents in older women, affects the hip, and may be bilateral.44 The joint may progress to complete destruction within a year or two. The cause of this rare condition is unknown,43 but it has recently been associated with the combination of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and anti-nerve growth factor antibodies.45,46 The hypothesis is that the analgesic effects of NSAID therapy result in increased mechanical loading of the hip, which impairs bone healing.43 Differential diagnosis requires the exclusion of septic arthritis, crystal disease, and avascular necrosis. OA usually presents with joint pain made worse with use (considered “mechanical” pain), short-duration stiffness after inactivity (termed gelling and commonly confused with the term locking), and sometimes audible grating on movement. Examination findings include tenderness on palpation, palpable grating on movement (crepitus), bony enlargement of the joint, effusion, malalignment, and reduction in the range of motion. As OA symptoms progress, muscle loss ensues with associated loss of function and with routine tasks becoming difficult. For example, people with OA of the hand may have trouble writing, turning door knobs, or opening jars. Similarly, older adults with knee or hip OA may have difficulty walking distances, getting out of chairs, or using steps. Additionally OA knee pain can be associated with a sensation of “giving way” (a symptom of muscle weakness), which may result in falls or affect the individual’s confidence, which may result in significant physical and mental health risks and contribute to fear and isolation. PAIN: OA pain is usually related to activity. In early disease, the pain may be episodic, evolving to more continuous pain over years, which may manifest at night, disturbing the person’s sleep. The impact of pain and disturbed sleep on psychological health should not be underestimated; depression is common in OA cohorts.47 The relationship between pain and imaging-assessed structural abnormalities in OA is complex and not completely understood. Radiographic changes do not correlate well with reported pain. Bone marrow lesions demonstrated on MRI correlate better with pain than radiographic changes.48 Imaging-detected synovitis has also been associated with OA pain.49 Such findings are not surprising: both the subchondral bone and synovium are well innervated, unlike the hyaline cartilage, although ingrowth of new nerves and blood vessels has been described in areas of cartilage loss.50 STIFFNESS: Stiffness refers to difficulty with, or speed of, joint movement, often after inactivity, such as first thing in the morning or after prolonged sitting. The ACR recognizes morning stiffness of less than 30 minutes duration as part of the diagnostic criteria for OA.51 DEFORMITY: The relatively common features of Heberden nodes and Bouchard nodes in OA of the hand is demonstrated in Figure 69-1. Varus, or less commonly valgus deformity, is common with OA structural progression at the knee. TENDERNESS: Tenderness along the joint line is a common finding in OA. Trochanteric bursitis is common in the presence of quadriceps muscle weakness (and often mistaken for hip OA). Anserine bursitis, medial and distal to the knee, is sometimes seen with OA of the knee. MUSCLE WASTING AND WEAKNESS: Quadriceps strength, knee pain, and age are more important determinants of functional impairment in older adult patients than the severity of knee OA as assessed radiographically.52 Difficulty getting out of chairs or cars is a common association with hip and knee OA. Asking the patient to squeeze your hand provides an assessment of grip strength, and assessing their ability to perform a slow straight leg raise (one leg at a time) on a flat couch gives a good indication of quadriceps strength. SWELLING: There may be palpable bony swelling of osteophytes. Effusions (related to synovial hypertrophy and increased volume of synovial fluid) are not uncommon. CREPITUS: This is a coarse grating sensation or sound that results from friction between two articular surfaces. It is best appreciated through the range of movement. Although a key feature in criteria, crepitus is a nonspecific sign of joint damage. A full history and examination is often all that is required to determine the diagnosis and extent and impact of OA on an individual. Investigations are uncommonly required except for differential diagnosis. IMAGING: The plain x-ray may be useful in differential diagnosis of a painful joint if history and examination are unhelpful. The main radiographic features of OA are loss of joint space, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral cysts, and osteophytosis. Weight-bearing views allow a better assessment of the extent of cartilage loss. It is important to remember that radiographic OA is common in the older adult population and may sometimes be an incidental finding. Overreliance on the radiograph for clinical decision making should be avoided; for example, radiographic OA would not exclude the presence of gout. Clinical judgment should be used to guide the uncommon requirement for other imaging modalities, such as MRI or ultrasound. LABORATORY FINDINGS: In clinical practice there is no specific laboratory test that can be used to confirm a diagnosis of OA. Unlike in cases of inflammatory arthritis, the acute-phase reactants in patients with OA are expected to be normal. SYNOVIAL FLUID ANALYSIS: In the presence of an effusion, an arthrocentesis can be a valuable test if inflammatory arthritis is suspected. In OA, the synovial fluid exhibits a low white blood cell count (<1000 cells/mm3). More importantly, synovial fluid analysis helps to confirm or exclude the presence of monosodium urate or calcium pyrophosphate crystals and also rule out sepsis, bearing in mind that a septic joint may present differently in an older patient as a result of the phenomenon of immunosenescence. Acquiring expertise in joint aspiration is of clinical value. Several international consensus guidelines for the management of OA are available.53–58 Therapeutic goals generally involve minimizing pain and disability while maximizing function and quality of life. Common to all guidelines is a holistic approach assessing the impact of OA on the individual. Treatment then incorporates a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options, including patient education, exercise programs, self-management, and weight loss strategies if overweight. Management plans should be individualized and consider the patient’s perceptions in order to maximize adherence; they must also be devised with consideration given to the potential toxicity of drugs such as NSAIDs and opioids.55 Key issues in the management of OA are presented in Table 69-4. TABLE 69-4 Key Issues in the Management of Arthritis in Older Adults Patients should be provided with key information about their prognosis, and misconceptions should be corrected: few people with OA will end up in a wheelchair, and the course of OA is not inevitably progressive. Patients should be encouraged to participate in self-management programs that help increase their understanding of the disease and educate them on treatment options available. Self-management programs may reduce health care utilization,59 and although they may not have a direct impact on pain or disability, these programs may help improve quality of life; in particular, they may help reduce anxiety and improve self-efficacy. There is a commonly held misconception that exercise may further damage the joints. Although avoidance of high-impact activity is advised, there is good evidence to show that tailored exercise programs can help significantly to reduce pain and disability.60 There are few contraindications, even in older people, to a “prescription of exercise” that combines stretching, strengthening, and aerobic routines.61 Exercise not only has a beneficial effect on pain and disability from OA but encourages restorative sleep, improves psychological health, promotes functional independence, and benefits comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, chronic heart failure, and hypertension. Correcting biomechanical factors is an important management strategy that can be of particular benefit in older adults. The use of a walking stick can help reduce the symptoms of hip or knee OA when held in the contralateral hand.55 Another example is the use of a hand splint in the setting of base of thumb OA. There are also recommendations on the use of suitable footwear providing shock absorption and adequate arch support. The use of a knee brace in OA of the knee with varus or valgus deformity and instability can not only reduce pain but also reduce the risk of falling.62 Using a multidisciplinary team approach and referring, when required, to the appropriate discipline, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or podiatry, is of great value. Nondrug treatment options should be a consideration in all patients with OA. The simple strategy of thermotherapy with the application of hot or cold packs to the affected joint is safe and low cost, even though evidence regarding effectiveness is limited. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2010 showed a short-term benefit of acupuncture in people with OA63 although a subsequent large trial showed no benefit of acupuncture over sham acupuncture.64 Drug treatment for OA needs individualized consideration as complications related to polypharmacy, drug toxicity, drug interactions, and comorbidities can occur. Generally, the analgesic effect of pharmacotherapy is small, and the evidence suggests that poorly designed trials overestimate the effectiveness of these therapies.62 TOPICAL THERAPIES: Topical NSAIDs such as diclofenac and ibuprofen were found to be safer than oral NSAIDs and the plasma concentration is substantially less than an equivalent dose of oral NSAIDs.65 Multiple daily applications may limit adherence. The U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that topical capsaicin may be useful in hand or knee OA, although some days of application may be needed before efficacy is evident.55 PARACETAMOL: Historically paracetamol has been commonly used for OA. It lacks contraindications or drug interactions and it is inexpensive. However, a recent meta-analysis suggested only a small analgesic benefit for paracetamol in OA, with questionable clinical significance.66 A meta-analysis of large observational studies reported some signals of toxicity, particularly in those taking high therapeutic doses; it wasn’t clear if this reflected paracetamol or whether paracetamol was highlighting a group using nonprescription NSAIDs (data that are difficult to capture in observational studies).67 ORAL NSAIDs: These drugs remain among the most commonly used analgesics for arthritis.68–69 Systematic reviews indicate that NSAIDs62 and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective agents show consistent good benefits across large numbers of studies.62 NSAIDs differ in their degrees of COX-1 and COX-2 selectivity; however, all classes of NSAIDs have associations with varying degrees of renal, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal risk, particularly in the older adult population with comorbidities (Table 69-5). Gastrointestinal risks may be compounded when NSAIDs are used in combination with paracetamol.70 Although COX-2 inhibitors have lower gastrointestinal side effects, similar to other NSAIDs they are associated with a prothrombotic risk. The NICE recommendations advise the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors with all NSAIDs.55 In patients at risk of cardiovascular complications, naproxen seems to have a better cardiovascular profile than other NSAIDs.71 In general, NSAIDs must be used with caution in frail older adults with OA,72 given that OA and cardiovascular disease often travel together.72–74 NSAIDs should be prescribed at the lowest possible dose for the shortest time duration. Great care needs to be taken when prescribing NSAIDs to older people and avoided altogether if possible, especially among those who are frail. OPIOIDS: Low-dose opioids are recommended in all OA guidelines, even though, like NSAIDs, they carry significant toxicity risks, especially in older adults. The evidence implies the analgesic effect size is bigger than that of simple analgesics.62 Confusion, constipation, and falls are major issues related to opioid use, especially in a frail population. Modified or slow-release preparations may be useful for night pain, and transdermal preparations may help compliance issues. INTRAARTICULAR CORTICOSTEROID INJECTIONS: The efficacy of intraarticular corticosteroids has been examined in a Cochrane review, confirming a modest and short-term efficacy of intraarticular corticosteroids in knee OA.75 There is no evidence to suggest superiority of any one kind of steroid preparation.71 The risk of infection with an intraarticular steroid injection is very small, although aseptic technique should of course be the norm. There have been concerns regarding cartilage toxicity with repeated injections, although this remains unproven. OTHER THERAPIES: Several nutraceuticals and food supplements are often used to treat older adults with OA. The best known are glucosamine and chondroitin; the evidence surrounding the efficacy of these agents in OA is mixed, and as a result, most contemporary guidelines do not recommend these therapies.55,76 There is currently an absence of randomized trial evidence to demonstrate analgesic efficacy of platelet-rich plasma or stem cell therapy in patients with OA, although trials are ongoing. SURGICAL TREATMENT: Total joint replacement remains a hugely successful procedure, although such replacements often last approximately 20 years and revision procedures (especially in the knee) are complex, so often total joint replacements are not offered to younger patients. Arthroscopy has not been demonstrated to be useful for OA knee symptoms. The 2014 NICE guidelines recommend that surgical intervention should not be offered to people suffering from OA until nonsurgical therapies have been adequately trialled.55 Surgery should be considered for those who continue to have symptoms that significantly impact their quality of life (rather than using a calculated scoring tool)77 and be offered before there is prolonged functional limitation that may diminish the benefits of surgery. The decision to refer someone with OA for surgery should not be restricted by patient-specific factors, such as age, smoking, obesity, or gender.55 NOVEL TREATMENTS: Several randomized controlled clinical trials have studied the effects of targeting subchondral bone pathology in subjects with OA, using bisphosphonates78–80 and strontium.81 These studies have shown mixed effects on pain, and these therapies require further investigation; selection of patients for certain subchondral bone pathologies (e.g., MRI-detected bone marrow lesions) may improve their benefits. More recently investigation has shifted to therapies that have anti-synovitis effects, based on the frequency of synovial inflammation in OA.82 Studies examining the role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockers have been disappointing.83 Preliminary data examining the role of methotrexate as an anti-synovitis therapy in knee OA has prompted further randomized controlled trials; results are pending.84 New approaches to understanding the pathology and pain pathways in OA open up more options, including centrally acting drugs such as duloxetine and tapentadol and peripheral agents such as those targeting nerve growth factor (such as tanezumab45,46). Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis and its prevalence (1% to 2%) has been increasing in recent decades, perhaps reflecting rising uric acid levels in communities. The presentation of gout may differ slightly in the older adult population from what is classically seen in younger community samples: it tends to have a more equal gender distribution and more frequently presents with polyarticular involvement.85 In older adults it is frequently associated with comorbid conditions such as chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. This adds complexity to the clinical presentation as well as its management. The clinical picture of gout arises from the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and soft tissue. Hyperuricemia is the single most important risk factor for the development of gout, and the progression of asymptomatic hyperuricemia to gout is, in part, a function of the duration and severity of the elevation of serum uric acid—in effect, a reflection of the total body burden of urate. It is important to consider the difference between asymptomatic hyperuricemia and gout: 90% of people with asymptomatic hyperuricemia will not progress to gout, and given current evidence, hyperuricemia does not require urate-lowering therapy.86 Large longitudinal cohort studies have shown that a number of dietary factors are associated with the development of gout by affecting the urate pool, including beer, spirits, sugar-sweetened soft drinks, fructose, red meat, and seafood.87 When urate levels exceed physiologic saturation thresholds, MSU crystals are formed and elicit an intense inflammatory response, including release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) by monocytes and macrophages, resulting in a severe painful inflammatory arthritis.88 Serum uric acid levels are affected by many factors, and rising or falling levels can trigger acute gout. Consequently, both increase in serum MSU (commonly as a result of dehydration or in increased cellular death following chemotherapy) and a fall in serum MSU as a result of urate-lowering therapy can trigger an attack. Common precipitants are presented in Table 69-6.89 TABLE 69-6 Precipitants of Acute Gout in Older Adults

Arthritis in Older Adults

Introduction

Category of Condition

Specific Diagnoses

Inflammatory

Gout and other crystal arthritis (i.e., pseudogout), rheumatoid arthritis, septic arthritis

Degenerative

Osteoarthritis, rotator cuff pathology, frozen shoulder, tendonitis

Vasculitis/connective tissue disease

Polymyalgia rheumatica, temporal arteritis

Back pain

Mechanical back pain, degenerative disc disease, osteoporotic vertebral fractures

Making a Diagnosis of Arthritis

Osteoarthritis

Hip

Knee (Clinical Criteria)

Hand

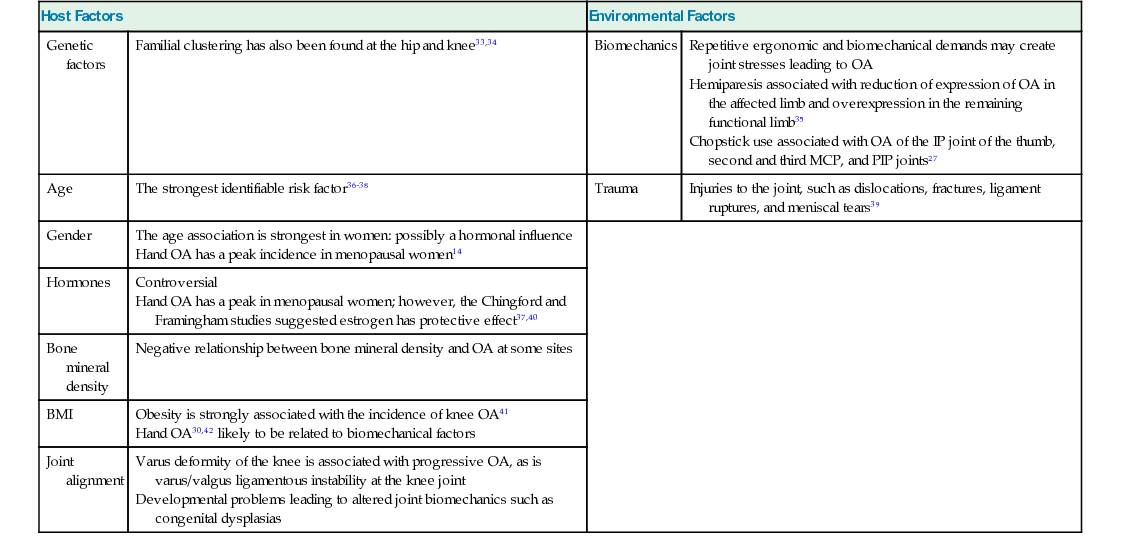

Host Factors

Environmental Factors

Genetic factors

Familial clustering has also been found at the hip and knee33,34

Biomechanics

Age

The strongest identifiable risk factor36–38

Trauma

Injuries to the joint, such as dislocations, fractures, ligament ruptures, and meniscal tears39

Gender

Hormones

Bone mineral density

Negative relationship between bone mineral density and OA at some sites

BMI

Joint alignment

Pathogenesis and Causes

Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis

Clinical Features

Investigations and Diagnosis

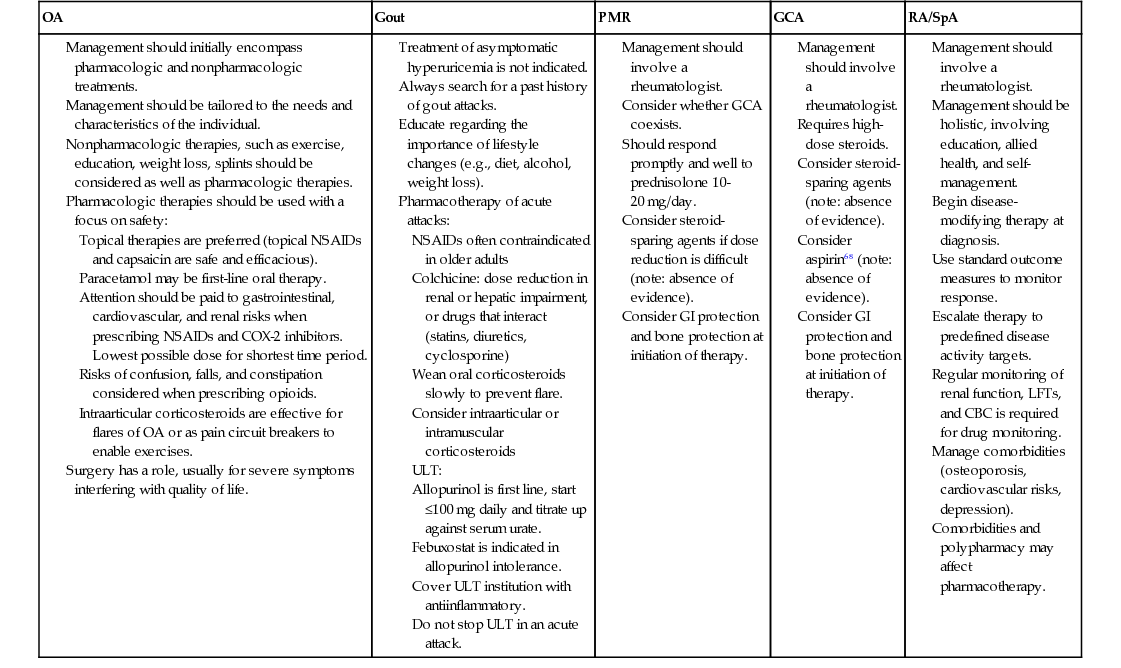

Management

Patient Education

Exercise

Optimizing Mechanical Factors

Nonpharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic Management

Gout

Pathogenesis

Arthritis in Older Adults

69