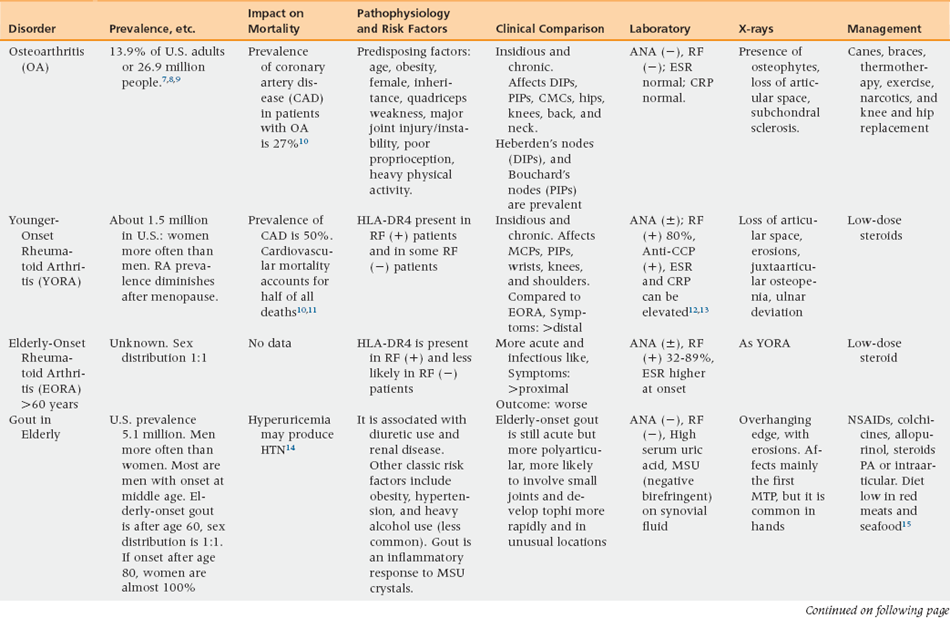

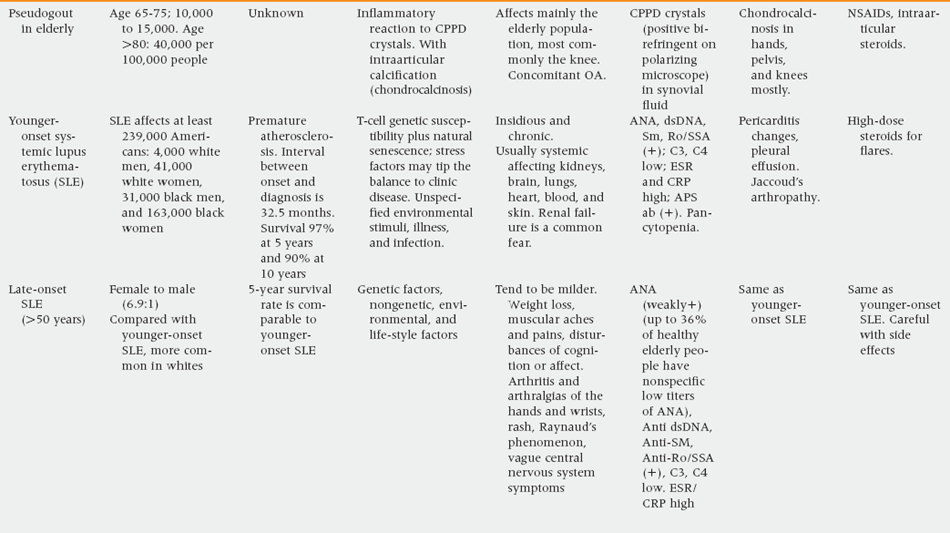

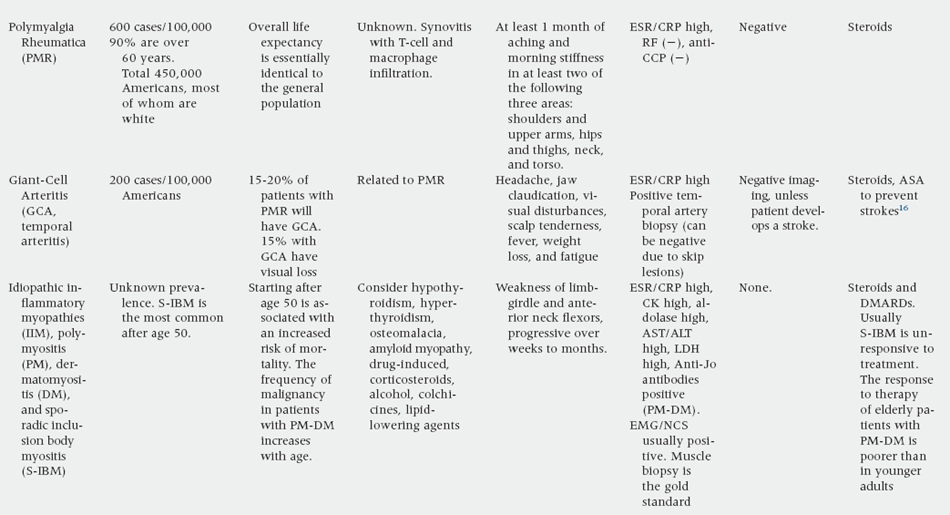

44 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the differential diagnosis of common rheumatic conditions affecting the older population. • Recognize that arthritis in later life is different from that in the younger population. • Understand strengths, limitations, and adverse effects of medications used to treat musculoskeletal disorders in older people. Arthritis is a common and prevalent condition that is acquiring more importance as the population ages. Models of care are proliferating to satisfy this demand through geriatric rheumatology or gerontorheumatology.1–6 Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common arthritic condition among the elderly, affecting 13.9% of U.S. adults, or 26.9 million people (Table 44-1). Other rheumatic disorders prevalent among the elderly are rheumatoid arthritis (RA; 1.5 million cases in the United States), gout (6.1 million cases), pseudogout (10,000 to 40,000 people ages 65 to 85), polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR; approximately 450,000 cases, 90% of whom are 60 years and older), and giant-cell arteritis (GCA; 110,000 Americans, 90% of whom are older than 60 years).6 OA, although highly prevalent in later life, does not appear to be directly caused by aging. Predisposing factors include obesity, female sex, quadriceps weakness, major joint injury and/or instability, poor proprioception, heavy physical activity, and genetics. OA is manifest first by cartilage irregularity, followed by eburnation or ulceration of the cartilage surface, and eventually by frank cartilage loss. PMR and GCA are closely related. The disease-initiating triggering of the immune system in PMR is unknown. GCA is a chronic, systemic vasculitis that affects the elastic membranes of the aorta and its extracranial branches, particularly the external carotid artery with its superficial temporal division.17,18 The differential diagnosis and assessment for arthritic conditions in older people is similar to that of younger individuals. Table 44-1 provides laboratory and x-ray studies to assist with assessment. A component of assessment is determining whether the symptoms with which the patient presents are atypical manifestations of typical diseases, as indicated in Table 44-2. TABLE 44-2 Atypical Musculoskeletal Manifestations of Typical Diseases OA usually has an insidious onset and chronic course. It affects the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints, causing characteristic Heberden’s nodes, and the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, causing Bouchard’s nodes. In addition, there is frequent involvement of the hips, knees, back, and neck. OA is a progressive disorder that takes many years to cause significant disability. Unfortunately, there is no cure. The development of Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes may take 1 or 2 years; they may be painful and soft initially and later harden and calcify as pain subsides. Two thirds of patients older than 65 years have x-ray changes consistent with OA.8 Laboratory studies reveal a negative antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and RA factor, and normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). X-ray films show osteophytes, with loss of articular space and subchondral sclerosis. RA tends to have a more acute presentation in older than in younger individuals, with more involvement of proximal joints. The diagnostic approach is similar to that used with younger individuals, with a positive rheumatoid factor (RF) in 80% of cases, positive anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 98% to 100%, and high ESR and CRP.12 A positive ANA is usually seen in patients with RA. X-ray studies show loss of articular space, multiple erosions, juxtaarticular osteopenia, and ulnar deviation. Arthrocentesis looks for three things in the synovial fluid: cell count, crystals, and culture. The information obtained will suffice in the differential diagnosis of most arthritic conditions. Noninflammatory fluids have less than 1000 white blood cells (WBC), whereas inflammatory fluids tend to have more than 2000 WBC. Fluids with more than 100,000 WBC indicate septic arthritis until proven otherwise. See Table 44-3 for conditions that cause inflammatory versus noninflammatory arthritides. Carefully selecting the kind of needle for this procedure is important. For instance, ordinarily, an 18-gauge needle can be used safely in the knee. If the patient is anticoagulated, a 22- or 25-gauge needle minimizes risk of bleeding. There should be an attempt to obtain clean, blood-free fluid for accurate analysis. As much fluid as possible should be drained with one needle-stick to minimize discomfort. There is no need to stop anticoagulation if the procedure is properly done.

Arthritis and related disorders

Prevalence

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis

Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Shoulder pain

Acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, costochondral pain, intraabdominal bleeding, or perforation

Temporomandibular

Acute myocardial infarction joint pain

Hip pain

Pancreatitis, psoas muscle abscess or hematoma, hip fracture, hernia

Back or extremity pain

Bone metastasis, osteomyelitis, tumor, or deep venous thrombosis

Myalgias

Rhabdomyolysis

Osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Role of arthrocentesis

Arthritis and related disorders