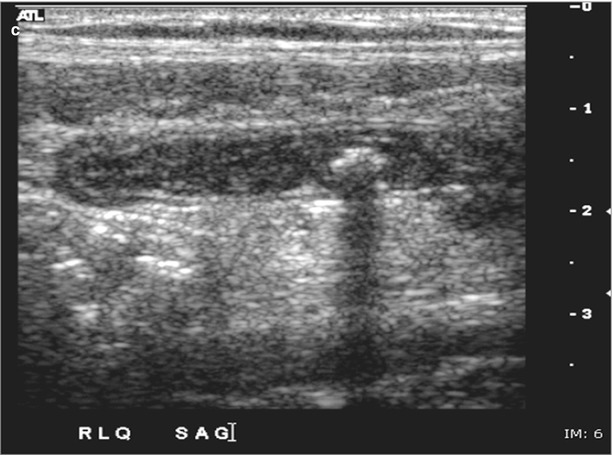

Fig. 11.1

(a) Ultrasound demonstrating a noncompressible tubular structure on ultrasound, with a transverse diameter of >6 mm, consistent with acute appendicitis. (b) Ultrasound demonstrating a longitudinal view of a noncompressible tubular structure with thickened walls consistent with acute appendicitis. (c) Endoluminal fecalith on ultrasound

The sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in the diagnosis of appendicitis ranged from 35 to 98 % and 71 to 98 %, respectively. The main advantages of ultrasound are its lack of radiation, the rapidity of results, and lack of contrast agents. The disadvantages of ultrasonography are its limited ability to diagnose other pathologic processes that may be occurring. In addition, the accuracy of ultrasound is operator dependent, and it may be difficult to image patients with obesity or with a large amount of overlying bowel gas. Currently, there are no studies focusing on the use of ultrasound in the diagnosis of appendicitis in elderly patients [35, 58–60].

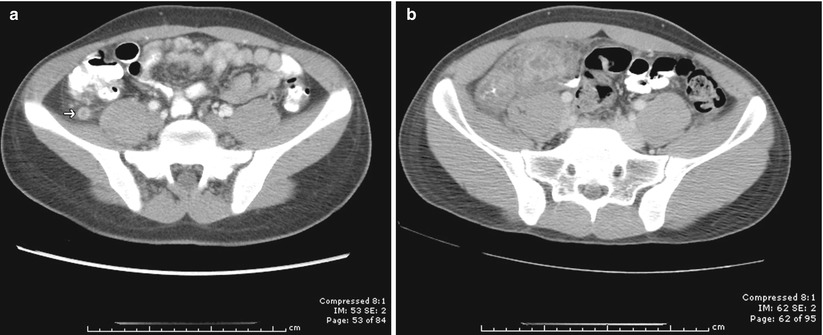

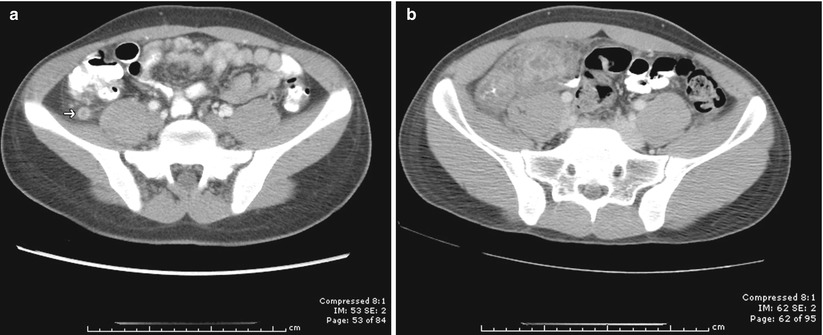

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis is frequently used in the radiographic diagnosis of appendicitis (Fig. 11.2a, b). CT findings of appendicitis include a nonfilling appendix that is thick walled and inflamed (appendix wall ≥7 mm), fat stranding around the appendix secondary to inflammatory changes, with or without periappendiceal fluid. A target sign with an appendicolith may be identified in 30 % of cases.

Fig. 11.2

(a) A target sign on CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis consistent with acute appendicitis. (b) Periappendiceal inflammation suspicious for perforated appendicitis

In a recently published study, Pooler et al. demonstrated that CT had a high sensitivity and specificity in elderly patients in whom the diagnosis of appendicitis was suspected. The overall diagnostic accuracy of CT is >99 %. This study also showed that despite a lower overall rate of acute appendicitis when compared to younger patients, the sensitivity and specificity of CT in elderly patients with clinically suspected appendicitis are statistically comparable to that of younger patients (sensitivity of 100 %, specificity of 99 %) [61]. This is the first study of its kind specifically examining the diagnostic performance of CT in an elderly population. Hui et al. also reported CT sensitivity of 91 % in elderly patients in whom appendicitis was clinically suspected [62].

Treatment

The goals of therapy for acute appendicitis should be timely diagnosis followed by prompt surgical intervention. Traditional surgical teaching has accepted a negative appendectomy rate of up to 20 % in patients diagnosed by clinical criteria. With advances in imaging technology, the acceptable negative appendectomy rate has been reduced to 10 %. It is well established that patients often delay seeking medical attention, causing the diagnosis of appendicitis to be difficult. This is especially true in elderly patients [35, 43–46, 53–60, 63]. The elderly tend to have a diminished inflammatory response, resulting in a less remarkable history and physical examination. For these reasons, older patients often delay seeking medical care, and as a result, they have a considerably higher rate of perforation at the time of presentation [44–46].

Whether open or laparoscopic techniques are used, surgical intervention remains the mainstay of treatment. In open appendectomy, a right lower quadrant incision should be the incision of choice. It has been shown that paramedian and vertical midline incisions, which might be used to explore patients in whom a definitive diagnosis has not been reached, are associated with higher postoperative infectious complications [46, 64].

Laparoscopic appendectomy can be used successfully in the elderly population and results in decreased length of stay, decrease postoperative complications, and decreased mortality for older patients with both perforated and nonperforated appendicitis [65–67].

There are a handful of circumstances in which appendectomy should be delayed. Patients who present early in their course of appendicitis will typically undergo immediate appendectomy. However, if a patient presents with a longer duration of symptoms (>72 h), they will likely have advanced appendicitis. These patients will often have a palpable mass on physical exam, and imaging studies may show a phlegmon or abscess. Operative intervention in patients with a long duration of symptoms and a phlegmon is associated with increased morbidity, due to dense adhesions and inflammation. Appendectomy under these circumstances will often require extensive dissection and may lead to injury of adjacent structures. Complications such as a postoperative abscess or enterocutaneous fistula may occur, necessitating an ileocolectomy or cecostomy. Because of these potential complications, a nonoperative approach can be considered if the patient is to be clinically stable. Many of these patients will respond to nonoperative management since the inflammatory process has already been “walled off.” Nonoperative management includes antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and bowel rest [68–71]. Repeat imaging may be necessary to document resolution of the phlegmon or progression to abscess formation.

If imaging studies demonstrate an abscess, CT- or ultrasound-guided drainage can be performed percutaneously [71–73]. Patients who have an abscess are ideal candidates for percutaneous drainage along with antibiotics, IV fluids, and bowel rest. This allows inflammation to subside, sometimes negating the need for extended bowel resection, such as ileocecectomy. This approach to appendiceal abscesses results in a decrease in morbidity and shorter lengths of stay [70, 74, 75]. Patients should be closely monitored in the hospital during this time. Treatment failure includes bowel obstruction, sepsis, or persistent pain, fever, or leukocytosis and requires immediate appendectomy. If fever, tenderness, and leukocytosis improve, diet can be slowly advanced. Patients are discharged home when clinical parameters have normalized.

More than 80 % of patients who present with a “walled-off” appendiceal process and undergo nonoperative management can be spared an appendectomy at the time of initial presentation. Traditionally, an interval appendectomy has been recommended for these patients 6–8 weeks after treatment [76]. The reason for this is to prevent recurrent appendicitis [77, 78] and to exclude neoplasms (such as carcinoid, adenocarcinoma, mucinous cystadenoma, and cystadenocarcinomas) [79, 80]. The need for interval appendectomy has been debated, with some studies suggesting that interval appendectomy is unnecessary [81, 82]. Kaminski et al., in a retrospective review of 1,012 patients treated nonoperatively for acute appendicitis, reported that 864 patients did not undergo interval appendectomy [81]. Of those 864 patients, only 39 (4.5 %) required an appendectomy at a median follow-up of 4 years. A meta-analysis of 61 observational studies in which a phlegmon or an appendiceal abscess was present found that immediate surgery was associated with higher morbidity than nonsurgical treatment. After successful nonsurgical treatment, a malignancy was detected in 1.2 % of cases, and recurrent appendicitis developed in 7.4 % of cases (95 %, CI 3.7–11.1) [82]. In the case of elderly patients, one must weigh the benefit of interval appendectomy against the risk of surgical intervention. Colonoscopy should be considered prior to appendectomy in patients over 50 who have not had a recent colonoscopy to rule out concurrent colonic pathology necessitating resection.

Outcomes

Despite improvements in the diagnosis and management of geriatric surgical patients, morbidity and mortality for appendicitis remain high. Morbidity rates between 28 and 60 % and mortality rates as high as 10 % are all significantly higher than younger patients. One explanation for this is that typically, geriatric patients with appendicitis tend to have an increased prehospital delay seeking medical attention which correlates with an increased rate of perforation. Whether young or old, patients with perforated appendicitis have increased lengths of hospital stay, an increased number of wound infections, and an increased number of hospital-acquired infections of all types (urinary tract, pneumonia). Patients with perforated appendicitis also have an increased rate of intra-abdominal septic complication, which, when coupled with the preexisting medical conditions often seen in elderly patients, leads to a high mortality for these patients [42–46, 63, 64, 83].

Malignancy and Mucocele

Cancer of the appendix is an uncommon finding, occurring in approximately 1 % of appendectomy specimens, and accounts for roughly 0.5 % of intestinal neoplasms. Carcinoid tumors are the most common, comprising over 50 % of appendiceal neoplasms. As is the case with other carcinoid tumors arising in the intestines, appendiceal carcinoids can secrete serotonin and other vasoactive substances. These substances are responsible for the carcinoid syndrome, which is characterized by episodic flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, and right-sided valvular heart disease. Nearly all appendiceal carcinoids are found retrospectively after an operation for acute appendicitis, and the majority of those are located at the tip of the appendix [84, 85].

Surgical management for appendiceal carcinoids is a subject of some debate. Since the vast majority is discovered incidentally in an appendectomy specimen done for other reasons, a decision must be made whether or not to return the patient to the operating room for a right colectomy. Tumor size is an important determinant of the need for further surgery [86]. Small appendiceal carcinoids (<1 cm) are often considered benign; however, regional metastases and/or deep invasion has been reported in tumors between 1 and 2 cm. For patients with tumors ≥2 cm, the 5-year mortality from appendiceal carcinoid is ~30 %, whereas with a 1 cm appendiceal tumors, there is a 5 % mortality rate at 5 years [87].

Whether a colectomy should be performed in some patients with smaller tumors is unclear. There is limited evidence on which to make clear recommendations for a right hemicolectomy in patients with a diagnosis of appendiceal carcinoid <2 cm. Hemicolectomy is advocated for tumors >2 cm, tumors at the base of the appendix, and incompletely resected tumor. For tumors <2 cm, if there is mesoappendiceal invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and intermediate- to high-grade tumors, and in patients with mixed histology (goblet cell carcinoid, adenocarcinoid) or with obvious mesenteric nodal involvement, some authors recommend right hemicolectomy. Others disagree and consider that appendectomy alone is adequate for tumors <2 cm, even with mesoappendiceal invasion. For carcinoids less than 1 cm in size and those between 1.0 and 1.9 cm without evidence of mesoappendiceal invasion or nodal involvement, simple appendectomy alone is adequate [87–91].

In contrast to other appendiceal neoplasms, the majority of patients with adenocarcinomas present with symptoms consistent with acute appendicitis. Patients can also present with ascites, generalized abdominal pain, or an abdominal mass. Appendiceal adenocarcinomas fall into one of three separate histologic types: the most common is the mucinous type and intestinal or colonic type (which closely mimics adenocarcinomas found in the colon) and the least common, signet ring cell adenocarcinoma [92–94].

In general, the optimal treatment for most appendiceal adenocarcinomas is a right colectomy, although this is debated. Some authors advocate a simple appendectomy for adenocarcinomas that are confined to the mucosa or well-differentiated lesions that invade no deeper than the submucosa. Although this distinction can be difficult to make intraoperatively, a more common scenario is the unexpected finding of an adenocarcinoma when the surgical report of an appendectomy specimen is finalized. In such cases, a right colectomy need not be pursued for appendiceal adenocarcinomas that are confined to the mucosa or well-differentiated lesions that invade no deeper than the submucosa [95]. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation for adenocarcinoma of the appendix is unknown. The rarity of this disease has precluded the performance of randomized studies, and few institutions see sufficient numbers of patients to report series of homogeneously treated patients.

The term appendiceal mucocele refers to any lesion that is characterized by a distended, mucus-filled appendix. It may be either a benign or malignant condition. The course and prognosis of appendiceal mucoceles are related to their histologic subtypes which include mucosal hyperplasia, simple or retention cysts, mucinous cystadenomas, and mucinous cystadenocarcinomas. Mucoceles that are due to hyperplasia, or that arise from an accumulation of mucus distal to an obstruction in the appendiceal lumen, even if they rupture, are benign and do not recur. Benign appendiceal mucoceles are usually asymptomatic. They may be diagnosed after appendectomy, or more commonly, they are found incidentally on a CT scan done for another purpose. In contrast, mucoceles that develop from true neoplasms (cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas) when ruptured can lead to intraperitoneal spread and the clinical picture of pseudomyxoma peritonei.

Surgical resection should be pursued, even for a benign-appearing appendiceal mucocele, since lesions that appear to be benign on imaging studies may harbor an underlying cystadenocarcinoma [96–99]. A right hemicolectomy is indicated in patients with a complicated mucocele with involvement of the terminal ileum or cecum. If there is no evidence of peritoneal disease and the final pathology shows a cystadenocarcinoma, a right colectomy could be considered to remove lymph nodes; however, the chance of nodal spread is quite small. An acceptable approach (assuming negative resection margins) is observation alone. If, on the other hand, there is evidence of peritoneal disease at laparoscopy, then the procedure should be converted to an open laparotomy for debulking.

Conclusions

Appendicitis is uncommon in elderly patients. However, when it does occur, elderly patients have poor outcomes. Delays in presentation and more rapid progression of disease contribute to poor outcomes. Elderly patients with significant comorbidities are less likely to tolerate the increased risk of complications associated with advanced disease. It is of the utmost importance that when an elderly patient presents to the hospital with abdominal pain, appendicitis be considered as a possible diagnosis. Rapid evaluation and management is important, and delay in treatment should be minimized whenever possible.

References

1.

Deaver JB. Appendicitis. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: P Blakiston’s Son & Co.; 1905.

2.

Major RH. Classic descriptions of disease. 3rd ed. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas; 1945.

3.

DeMoulin D. Historical notes on appendicitis. Arch Chir Neerl. 1975;27:97–102.

5.

Amyand C. Of an inguinal rupture, with a pin in the appendix caeci, incrusted with stone; and some observations on wounds in the guts. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1736;39:329–36.

7.

Fitz RH. Perforating inflammation of the vermiform appendix: with special reference to its early diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med Sci. 1886;92:321–46.

8.

Brooks SM. McBurney’s point: the story of appendicitis. New York: AS Barnes & Co; 1969.

9.

Klingensmith W. Establishment of appendicitis as a surgical entity. Tex State J Med. 1959;55:878–82.PubMed

10.

McBurney C. Experience with early operative interference in cases of disease of the vermiform appendix. NY Med J. 1889;50:676–84.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree