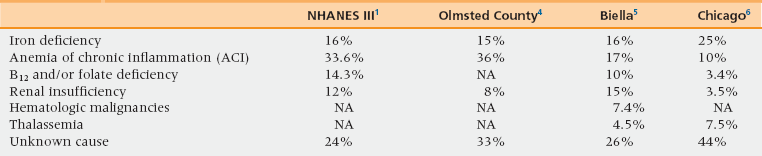

47 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Define anemia in the older aged person. • Discuss the medical consequences of anemia. • Outline the treatment of anemia, and explain how to address the medical consequences of the disease. As is the case with the majority of diseases, the incidence and prevalence of anemia increase with age.1–8 The prevalence of anemia is higher among institutionalized than among home-dwelling older individuals.9–12 With the aging of the population one may expect anemia to become an increasingly common problem. The WHO defines anemia as hemoglobin concentrations less than 13.5 g/dL for men and less than 12.0 g/dL for women.13 According to this definition the prevalence of anemia is higher in men than in women after age 65 and is higher in black than in white people for any age group. A number of recent studies have questioned the WHO definition of anemia in older women. The Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS), a prospective study of 1003 women 65 and older living in the Baltimore area, showed that hemoglobin levels lower than 13.4 g/dL represented a risk factor for mortality and values lower than 13.0 g/dL a risk factor of disability and functional dependence.14,15 Likewise, the Cardioascular Health Study (CHS) found that hemoglobin levels below 12.6 g/dL were an independent risk factor for mortality in women 65 and older.16 Based on these findings it would appear reasonable to consider the lowest normal hemoglobin levels in older women to be between 12.5 and 13.0 g/dL. When these levels are adopted, the difference in incidence and prevalence of anemia between older men and women disappears. The issue of whether African Americans should be considered anemic at lower hemoglobin levels than individuals of other races is still controversial. A recent study of the population aged 70 to 79 in Memphis, Tenn., revealed that the risk of mortality and functional disability for older blacks increased only for hemoglobin levels 2 g lower than the WHO standard, over a 2-year observation time.7 At the same time, a longitudinal study of older African Americans at Duke University showed that the risk of mortality and disability was higher when levels of hemoglobin were below the WHO standards.17 Similar finding were reported in a longitudinal study of individuals 65 and older in Chicago, over 13 years.18 For the present time it appears prudent to consider older African Americans with hemoglobin levels lower than the WHO standards to be anemic. The causes of anemia in older individuals in the outpatient setting are shown in Table 47-1.1,4,5,6 Two recent studies conducted in specialized anemia clinics explored the causes of anemia in the older aged person. The variation between different studies may be partly explained by the fact that they were conducted at different times and in different populations. Patients in the Biella5 and the Chicago6 studies underwent an intensive evaluation of the causes of anemia as they were followed in a specialized anemia clinic. The causes of anemia were not consistently investigated in either the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)1 or the Olmstead county studies.4 Despite these differences some common trends are recognizable: • In more than 50% of cases anemia has a cause that is both recognizable and treatable. Thus a thorough investigation of the causes of anemia, even of mild anemia, in older individuals is warranted. • In at least a third of cases the cause of anemia remains unexplained, even after an intensive workup. In the Biella study eventually one fourth of the patients with anemia of unknown causes developed myelodysplasia during the follow-up period. The main cause of iron deficiency in older age is blood loss, especially from the gastrointestinal tract,19–22 which should be thoroughly evaluated even in the absence of symptoms and in the presence of negative hemoccult stool test. At the same time it is important to remember that in 30% to 50% of adults a cause of blood loss is not identified and iron malabsorption may be the main cause of iron deficiency. Causes of iron malabsorption may include atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, and celiac disease. In the presence of iron malabsorption, oral iron therapy may be ineffective. The incidence and prevalence of B12 deficiency increase with age.23,24 The most common cause of B12 deficiency is the inability to digest B12 in food because of decreased gastric secretion of hydrochloric acid and pepsin; people with this condition may respond to oral crystalline B12.23,24 Drug-induced B12 deficiency is increasingly common,25 especially with the use of proton pump inhibitors and metformin. In addition to anemia, B12 deficiency may be a cause of neurologic disorders including dementia, and posterior column lesions. The anemia of unknown causes represents a special diagnostic challenge. Some of these patients may represent early cases of myelodysplasia or unrecognized chronic renal insufficiency. In some studies, as many as 75% of patients develop anemia when glomerular filtration rate is lower than 60 mL/minute.26,27 These values are common in individuals 65 and older and are almost universal after age 80. Hypogonadism may account for some of these cases.28 The role of hypogonadism was highlighted in the Chianti study, which found low levels of circulating testosterone in three fourths of older men and women with anemia. In addition, low testosterone levels were highly predictive of future development of anemia in nonanemic subjects. The possibility of preventing or reversing anemia with testosterone replacement needs study. After aromatization to estrogen, androgens stimulate the proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells through estrogen receptor alpha that activates the ten-eleven-translocation (TET) gene and leads to increased telomerase synthesis.29 It is worth remembering that hormonal treatment of cancers, such as androgen deprivation for prostatic cancer and aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer, may cause anemia through this mechanism. Nutrition may play an important role in anemia of unknown causes.30 In addition to protein/calorie malnutrition that becomes more common with aging, a lack of specific nutrients may be important. Recent studies identified deficiency of vitamin D31 and copper32 as potential causes of anemia in older individuals. Relative erythropoietin deficiency appears central to most cases of anemia of unknown cause in the elderly. In the anemia clinic of the University of Chicago,6 older patients with anemia of unknown causes failed to show an increase in erythropoietin with a drop in hemoglobin levels, unlike patients with iron deficiency in whom an inverse relationship existed between circulating levels of erythropoietin and hemoglobin. Ferrucci et al. found that the levels of erythropoietin were more elevated in the presence of normal hemoglobin levels, but failed to increase appropriately when hemoglobin levels dropped, in patients with increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines in the circulation.33 Inflammatory cytokines may both reduce the sensitivity of erythropoietic precursors to erythropoietin and inhibit erythropoietin secretion. In other words, most cases of anemia of unknown origin would represent a form of anemia of inflammation. This is reasonable because aging is seen as a form of chronic and progressive inflammation.34 This hypothesis, however, is questioned by a recent study showing that no relation exists between the excretion of hepcidin in the urines of older individuals and their hemoglobin levels.35 Hepcidin is key to the pathogenesis of anemia of inflammation.36 This enzyme shuts down the transport of iron from the gastrointestinal tract and from bone marrow stores by destroying the iron-transporting protein ferroportin. The production of hepcidin occurs in the liver and is stimulated by inflammatory cytokines, and in particular interleukin 6. An area of controversy is whether anemia may develop in older individuals in the absence of a specific disease from exhaustion of hematopoietic reserves, which may include numeric as well as functional abnormalities of the hematopoietic stem cells and failure of the hematopoietic microenvironment to support the viability of these elements. In some cross-sectional studies the average hemoglobin levels appeared consistent in all age groups at least up to age 85, though the prevalence of anemia increased with age.37–40 These data suggested that anemia is not a necessary consequence of age. Two longitudinal studies, one from Japan41 and the other from Sweden,42 revealed a small but progressive decline in hemoglobin concentration with age. Such findings suggest that a progressive erythropoietic exhaustion of low degree may occur with aging. It may become significant under conditions of erythropoietic stress, such as blood loss with a delayed and incomplete correction of anemia. Because anemia may have multiple causes in up to 50% of anemic older people,5 the diagnosis of the causes of anemia in the older person involves some unique problems. Perhaps the most important diagnostic issue is the recognition of iron deficiency in the presence of anemia of inflammation (Table 47-2). A foolproof diagnostic test does not exist, but elevated levels of soluble transferrin receptors and low circulating levels of hepcidin suggest some degree of iron deficiency. In this situation an improvement of anemia following iron treatment confirms the diagnosis of iron deficiency. The distinction is important not only for therapeutic reasons. A diagnosis of iron deficiency should trigger investigations for occult bleeding.20 TABLE 47-2 Differentiating the Anemias of iron Deficiency and Chronic Inflammation

Anemia

Definition of anemia

Causes of anemia (box 47-1)

Anemia of Inflammation

Iron-Deficiency Anemia

Serum iron

Low

Low

Total iron-binding capacity

Decreased

Increased

Ferritin levels

Increased

Decreased ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access