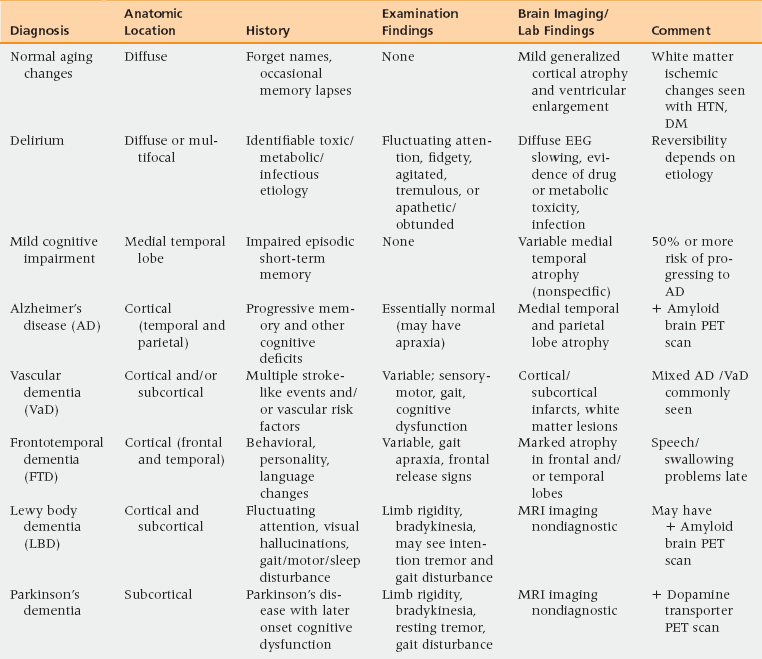

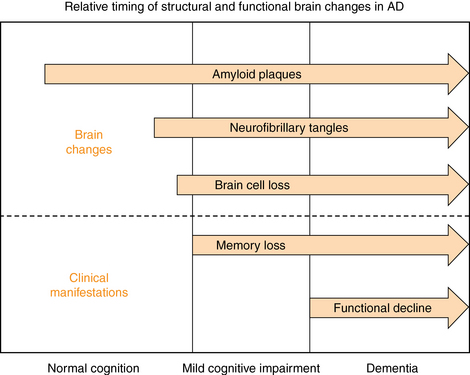

17 Pathophysiology and Differential Diagnosis Screening for Cognitive Impairment Diagnostic Evaluation of the Person with a Positive Screen for Cognitive Impairment Management of Mild Cognitive Impairment Medication for Cognitive Symptoms Management of Behavioral Symptoms Management of Depression in Dementia Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Understand the signs, symptoms, and diagnostic approach to the following common cognitive disorders of older persons: Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and Parkinson’s dementia. • Be able to conduct and interpret a screening examination for cognitive impairment, using the Mini-Cog and the AD-8. • Be able to conduct and interpret a diagnostic evaluation of a patient with cognitive impairment using cognitive testing, laboratory studies, and brain imaging. • Understand and be able to implement basic principles of dementia management, including medication use, nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms, and working with community resources. Dementia is a progressive, global deterioration of cognitive ability in multiple domains including memory and at least one of the following: orientation, learning, language comprehension, and judgment.1 The deterioration is severe enough to interfere with daily life. Approximately 5 million persons in the United States have dementia.2 Dementia increases dramatically with age, so that the frequency of dementia among persons age 65 to 70 is approximately 2%, whereas for persons older than 85 it is more than 30%, costing $172 billion annually.2 Not all cognitive complaints reflect dementia, however; in fact, nearly twice as many persons with cognitive impairment have milder symptoms that do not meet criteria for dementia.3 Patients usually first discuss symptoms with their primary care physician. Among those diagnosed with dementia, 70% have Alzheimer’s disease (AD).4 Assessing cognitive impairment and diagnosing and managing dementia will be an increasingly important component of primary care medicine. Clinicians must be adept at assessing and monitoring patients who have mild cognitive symptoms, and identify those who develop a progressive dementia. Particularly challenging is the fact that the onset of dementia is insidious and the transition from normal age-related cognitive lapses to diagnosable dementia is gradual and, therefore, difficult to detect. Consequently, every clinician needs to develop a systematic approach to dementia screening and evaluating patients with cognitive impairment, and have a working knowledge of the common dementias. AD typically affects the hippocampus and adjacent temporal lobe regions initially, resulting in the loss of the capacity to learn and retain new information.2 In AD, evidence suggests that there are two well-recognized pathophysiologic proteins present—neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques—which are interconnected and lead to progressive neuronal death.4 • Nonmodifiable risk factors include age, family history, the APOE-4 gene, and Down’s syndrome. • Modifiable or potentially preventable risk factors include prior head trauma, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and depression. Age is the strongest known and best-studied risk factor.2,5 The overall prevalence of dementia doubles for every 5-year increase in age after age 65. After age 85, the risk reaches nearly 50%.5 A family history of AD is another strong risk factor; individuals with both parents having AD have a 54% cumulative risk of developing AD by age 80. First-degree relatives of patients with AD appear to have a cumulative lifetime risk of AD of 39%, twice the risk for the general population.6 Several genetic mutations have been associated with increased risk of AD. The risk gene with the strongest influence is apolipoprotein E-e4 (APOE-e4). Scientists estimate that APOE-e4 may be a factor in 20% to 25% of Alzheimer’s cases.7 Those who inherit APOE-e4 from one or both parents have a higher risk of AD, with homozygotes having a higher risk than heterozygotes. In addition to increasing risk, APOE-e4 is associated with an earlier onset of AD.1 Scientists have also discovered genetic variations that directly cause rare, early-onset familial AD with onset of disease occurring prior to age 65. These mutations are found on the genes coding for three proteins: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PS-1), and presenilin-2 (PS-2).8–10 Down’s syndrome is also a risk factor for AD, with 75% of people with Down’s syndrome age 60 and older having AD.11 Head trauma and traumatic brain injury are also risk factors for all dementias; the odds ratio is from 1.3 to 1.9.5 Clinicians should consider anxiety and depression to be premorbid risk factors of dementia. A case-control study suggested that a diagnosis of anxiety was strongly associated with a dementia diagnosis after adjustment for other risk factors (odds ratio 2.76; 95% confidence interval: 2.11-3.62).12 What is unclear is whether these disorders represent a link in the causal chain or (as appears more likely) awareness of early cognitive loss. The most common cause of dementia in the elderly is AD, and many affected individuals exhibit isolated memory problems before developing full-blown AD. AD’s course tends to be insidious in onset and slowly progressive, eventually leading to impairment of basic bodily functions, and finally—if no other illness intervenes—to death. In 2011 new criteria and guidelines for the diagnosis of AD were published by the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Institute on Aging (NIA). The new guidelines focus on three stages of AD: (1) preclinical (presymptomatic) Alzheimer’s dementia, (2) mild cognitive impairment (MCI) resulting from Alzheimer’s, and (3) dementia resulting from Alzheimer’s. Further recommendations by this group describe the use of biomarkers in Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI caused by Alzheimer’s as not intended for application in clinical settings at this time.13 • In a “preclinical” disease stage, the disease has not yet caused any noticeable “clinical” symptoms, because brain changes caused by the disease begin years before symptoms such as memory loss and confusion occur. The recommendations in the article on preclinical AD are intended for research purposes only. They have no clinical utility at this time. • Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) caused by AD encompasses changes in memory and thinking abilities that are noticeable to the person and to family members and friends and that can be measured, but that do not affect one’s ability to carry out everyday activities. Many, but not all, people with MCI go on to develop dementia caused by AD.13 • As AD pathology progresses, multiple cognitive domains become affected, leading to clinically significant functional impairment.2,13 Behavioral problems frequently develop such as depression, apathy, anxiety, agitation, psychosis, and wandering.2 Pathologically, these clinical manifestations are associated with the presence of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, resulting in neuronal dysfunction and cell death. Figure 17-1 graphically illustrates this new model of the time course of AD. Figure 17-1 Schematic diagram for sequence of brain pathological changes beginning with asymptomatic (AD Stage 1) amyloid plaque deposition, followed by neurofibrillary tangle formation and associated neuronal dysfunction and destruction, resulting in initial memory disturbance (AD Stage 2), which progresses over time into clinically significant cognitive and functional changes, i.e., dementia (AD Stage 3). The suspicion that a person has cognitive impairment usually arises either because the clinician senses something abnormal during history-taking for an unrelated complaint, or because a family member brings up concerns about memory or thinking problems. When a suspicion arises or when the patient is at high risk for dementia (e.g., older than 75, family history), cognitive screening should be undertaken. The goal of cognitive screening is to identify persons who merit a more detailed diagnostic evaluation. When a person screens positive, care should be exercised to assure that a positive screen does not necessarily indicate a diagnosis of dementia, but rather, that further evaluation is indicated. Current recommendations by the American College of Physicians, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the Alzheimer’s Association discourage routine screening for dementia on all older patients at a certain age. Screening is only recommended if a patient sees a doctor about some type of problem that could be resulting from dementia. However, a study that contradicted these current guidelines concluded that routine screening at primary care clinics led to a twofold to threefold increase in diagnoses of cognitive impairment.14 The Mini-Cog provides a brief, valid, reliable, and uncomplicated measure for use in primary care as a routine screen for cognitive impairment.15,16 The test consists of a 2-step assessment: a 3-item memory task (registration and later recall), with an intervening clock-drawing task serving as a distractor. The Mini-Cog is scored as a binary outcome (demented/not demented) based on the recall score alone (0/3 = demented, 3/3 = not demented) or in conjunction with the clock-drawing task, if recall performance is equivocal (1-2/3). The Mini-Cog is both highly sensitive and highly specific for dementia when used in a community-based elderly population.15,16 The Mini-Cog can be supplemented by asking the patient’s spouse or other family members to complete the AD-8. The AD8 is a brief, validated tool in which a family informant answers eight questions about the presence or absence of memory and other cognitive impairments.17 The AD-8 is both sensitive (sensitivity >84%) and specific (specificity >80%). It has a positive predictive value of >85% and a negative predictive value >70% in detecting early cognitive changes associated with many common dementia-causing illnesses, including AD, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (LBD), and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).2,18 It is estimated that as many as 10% to 20% of people age 65 and older have MCI.19 MCI is classified into two subtypes: amnestic and nonamnestic. Amnestic MCI is present when the person has isolated memory loss; nonamnestic MCI involves impairment in areas other than memory. Amnestic MCI has a more ominous prognosis and is associated with a high risk of progression to AD.20 The annual rate of progression to dementia among healthy community-living adults aged 55 and older is about 1% to 2% per year; in contrast, the annual conversion rate from amnestic MCI to dementia is 6% to 22% per year, with about 50% having dementia within 5 years.19,20 The differential diagnosis of cognitive impairment includes normal aging changes, mild cognitive impairment, delirium, and numerous dementia diagnoses. Table 17-1 summarizes these conditions. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) replaces the term “dementia” with “neurocognitive disorder”, broadly divided into a minor category (i.e., MCI), and a major category, commensurate with the syndromic definition of dementia.13 These criteria accurately identify AD on clinical grounds, whereas diagnostic criteria for other dementias (e.g., vascular dementia, LBD, FTD) are not as robust.21 Compared to AD, other dementias tend to have more variable clinical presentations, which makes defining diagnostic criteria more difficult. Dementia, as defined in DSM-V, stands in contrast with delirium, which is distinguished by a primary alteration in attentional processing. Although dementia syndromes tend to be chronic, progressive, and irreversible, and delirium states tend to be acute to subacute, fluctuating, and reversible, these distinctions are more relative than absolute. Toxic, metabolic, and infectious disturbances associated with delirium are more likely to be potentially reversible than degenerative disorders. Brain dysfunction associated with dementia may render the patient more vulnerable to delirium-producing factors, highlighting the clinical challenge posed by the combination of dementia and superimposed delirium. Careful evaluation of persons referred for dementia can identify treatable or reversible disorders in up to 20% of cases, though treatment of the reversible component will rarely eliminate all deficits.22 Distinguishing cognitive impairment associated with an underlying brain disorder from potentially reversible cognitive symptoms (e.g., associated with depression) often demands ongoing evaluation, including appropriate diagnostic tests and perhaps therapeutic challenge with an antidepressant drug. Abrupt onset of thinking changes in temporal relation to a psychological stressor, poor effort on cognitive testing (particularly with demanding tasks), and prominent neurovegetative signs such as insomnia and anorexia are characteristic of depression-associated cognitive impairment. Drug-induced cognitive impairment occurring as a result of anticholinergic agents, sedative-hypnotic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines), or opiate analgesics is common in the elderly and may variably cause or contribute to symptoms of dementia or MCI. A temporal association of cognitive symptom onset with the initiation or increase in dosing of such drugs should prompt withdrawal of any potentially offending agent. Accurately diagnosing dementia usually requires a systematic, longitudinal approach and, in many cases, targeted therapeutic additions or deletions. Multiple etiological factors are common, and the search for potentially reversible or modifiable conditions should be pursued vigorously (Table 17-2). TABLE 17-2 Potentially Treatable and/or Reversible Causes of Cognitive Impairment

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias

Prevalence and impact

Pathophysiology and differential diagnosis

Risk factors for alzheimer’s disease

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic approach

Screening for cognitive impairment

Mild cognitive impairment

Diagnostic evaluation of the person with a positive screen for cognitive impairment

Cause

Findings Raising Clinical Suspicion

Method of Diagnosing or Ruling Out

Medication adverse effects

Patient is on anticholinergic drugs (e.g., diphenhydramine), sedative medication (e.g., benzodiazepines), or narcotic analgesics

Medication review

Withdrawal challenge

Hypothyroidism

Fatigue, cold intolerance, constipation, weight gain, bradycardia (but typical signs may be absent in elderly)

History and physical

TSH

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Very poor diet/strict vegetarianism; paresthesias, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy

Vitamin B12 level

Neurosyphilis

Grandiosity, confabulation, emotional lability, Argyll Robertson pupils

Serum FTA

Spinal fluid FTA

Brain tumor

Headache, nausea/vomiting, seizures, focal neurologic signs

MRI or CT of the head with contrast

Normal pressure hydrocephalus

Wide-based gait, urinary incontinence early in course of cognitive impairment

MRI or noncontrast CT scan of the head

Lumbar puncture

Subdural hematoma

History of trauma (often minor), fluctuating level of consciousness, headache, focal neurologic signs

Noncontrast CT scan of the head

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias