Allergic and Nonallergic Reactions to Food

Stephen R. Boden

Wesley A. Burks

I. ALLERGIC AND NONALLERGIC FOOD REACTIONS

The term “food allergy” has often been used to denote any adverse reaction after ingestion of a food. This broad definition has come to encompass both hypersensitivity and intolerance reactions to food proteins. While these reactions each occur after the ingestion of food, the processes involved are unique and not interchangeable.

A. Food intolerance

Food intolerance describes an atypical reaction following the ingestion of a food or food additive. This reaction is not mediated by the immune system and may be caused by any number of factors. For example, Scombroid fish poisoning or toxins secreted by bacteria such as Salmonella, Shigella, or enterotoxin-producing Escherichia coli may result in gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms following ingestion of contaminated food. Metabolic abnormalities such as those seen with lactose intolerance may contribute to food intolerance. Pharmacologically active components of food, like caffeine, may also elicit adverse reactions.

B. Food hypersensitivity

Food hypersensitivity results from the sensitization to a specific food protein and may develop after exposure to small amounts of food protein. Most physicians associate food hypersensitivity with immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated anaphylaxis, although non-IgE-mediated reactions also occur. In IgE-mediated food allergy, the patient develops specific IgE directed against a portion of the food protein. This food-specific IgE is then bound to high-affinity receptors found on tissue mast cells and basophils. Upon reexposure to the food, IgE molecules bound to these high-affinity receptors are crosslinked and trigger the release of preformed mediators (i.e., histamine and tryptase) as well as induce mediator synthesis (i.e., leukotrienes and prostaglandins), leading to anaphylaxis. Although IgE-mediated (type I) reactions are well characterized and account for the majority of food hypersensitivity, non-IgE-mediated immune responses are thought to play a role in several disease processes. Both IgE- and non-IgE-mediated diseases will be discussed in this chapter.

C. Epidemiology

Establishing an accurate incidence for food reactions has proven difficult for several reasons. As discussed above, the lack of a universally applied definition for food allergy may lead to inappropriate inclusion or exclusion of a reaction. Additionally, many food reactions are not reported to the health care system when symptoms are mild or are not recognized. Published studies indicate that self-reported incidence of food allergy overestimates the actual incidence in the population. In one study, 12% of children and 13%

of adults reported having an allergy to food, while only 3% of all ages were found to have a positive history of food reaction accompanied by objective findings with an oral food challenge, skin prick test (SPT), or in vitro food-specific IgE testing. Current studies estimate the prevalence of specific food allergy in the population at 0.9% allergic to milk, 0.3% allergic to egg, 0.75% allergic to peanut, 0.3% allergic to fish, and 0.6% allergic to shellfish.

of adults reported having an allergy to food, while only 3% of all ages were found to have a positive history of food reaction accompanied by objective findings with an oral food challenge, skin prick test (SPT), or in vitro food-specific IgE testing. Current studies estimate the prevalence of specific food allergy in the population at 0.9% allergic to milk, 0.3% allergic to egg, 0.75% allergic to peanut, 0.3% allergic to fish, and 0.6% allergic to shellfish.

II. IgE-MEDIATED DISEASE

Food hypersensitivity mediated by IgE may affect multiple organ systems, and not every organ system need to be involved with each episode. The signs and symptoms of IgE-mediated reactions may be found in the chapter on anaphylaxis.

III. POLLEN-ASSOCIATED FOOD ALLERGY SYNDROME

Pollen-associated food allergy syndrome, also called oral allergy syndrome, is confined almost exclusively to the oropharynx, rarely involving other organ systems. Associated with the ingestion of fresh fruits or vegetables, symptoms arise quickly after exposure and are generally self-limiting. Common symptoms include itching and/or swelling of the lips, tongue, soft palate, and the throat. Symptoms are the result of IgE cross-reactivity between food proteins and wind-borne pollen. Ragweed and birch pollen are frequently identified. Exposure to cooked or preserved fruits and vegetables does not provoke symptoms, suggesting a conformational change alters IgE binding and mast cell activation. Table 16-1 provides a list of common foods and the pollen that may trigger these symptoms.

IV. FOOD-INDUCED ANAPHYLAXIS

Food-induced anaphylaxis, commonly called food allergy, typically occurs within 2 hours of eating the trigger food. Up to 80% of patients will experience

cutaneous symptoms. Acute urticaria or angioedema is seen most commonly. The absence of skin symptoms can lead to failure to diagnose anaphylaxis. Respiratory symptoms include edema of the nasal mucosa, congestion, nasal and/or ocular pruritus, tearing, rhinorrhea, and sneezing. The lower airway may also be involved with cough, voice changes, or wheezing. When affecting the GI tract, anaphylaxis may cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramping, and diarrhea. The percentage of patients experiencing symptoms may be found in the chapter on anaphylaxis. Symptoms usually develop suddenly and may progress quickly without intervention. Recognition of anaphylaxis and rapid treatment, as discussed elsewhere, is essential for patient safety. Although any food may trigger an anaphylactic reaction, most are caused by a small number of foods. Ninety percent of food-induced anaphylaxis in children is triggered by cow’s milk, hen’s egg, peanut, tree nut, soy, wheat, or fish. In adults, this list includes shellfish as well. Fatal food anaphylaxis is seen most often in adolescents with a known food allergy who fail to receive injectable epinephrine in a timely manner. A history of asthma or of a prior severe food reaction also increases the risk of fatal food anaphylaxis. The natural history of food allergy is currently under investigation. Published results at this time indicate that up to 80% of children with allergy to milk and egg will develop tolerance between 5 and 16 years of age. Contrastingly, only about 20% of children with peanut allergy will develop tolerance in the same time period. Allergies developed in adults also are more likely to persist even with strict avoidance. The mechanism by which tolerance develops is still unknown; however, those who do develop tolerance tend to have lower food-specific IgE at the time of diagnosis. It should be noted that the severity of food allergy reactions has not been correlated with size of SPT, level of specific IgE, or amount ingested resulting in allergic reaction. Cross-reaction seen in IgE testing between similar foods has been demonstrated, for example, legumes (i.e., peanut and soy) and milk (i.e., cow’s milk and goat’s milk). Table 16-2 lists several foods that may cross-react within a family and the likelihood of clinical significance.

cutaneous symptoms. Acute urticaria or angioedema is seen most commonly. The absence of skin symptoms can lead to failure to diagnose anaphylaxis. Respiratory symptoms include edema of the nasal mucosa, congestion, nasal and/or ocular pruritus, tearing, rhinorrhea, and sneezing. The lower airway may also be involved with cough, voice changes, or wheezing. When affecting the GI tract, anaphylaxis may cause nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramping, and diarrhea. The percentage of patients experiencing symptoms may be found in the chapter on anaphylaxis. Symptoms usually develop suddenly and may progress quickly without intervention. Recognition of anaphylaxis and rapid treatment, as discussed elsewhere, is essential for patient safety. Although any food may trigger an anaphylactic reaction, most are caused by a small number of foods. Ninety percent of food-induced anaphylaxis in children is triggered by cow’s milk, hen’s egg, peanut, tree nut, soy, wheat, or fish. In adults, this list includes shellfish as well. Fatal food anaphylaxis is seen most often in adolescents with a known food allergy who fail to receive injectable epinephrine in a timely manner. A history of asthma or of a prior severe food reaction also increases the risk of fatal food anaphylaxis. The natural history of food allergy is currently under investigation. Published results at this time indicate that up to 80% of children with allergy to milk and egg will develop tolerance between 5 and 16 years of age. Contrastingly, only about 20% of children with peanut allergy will develop tolerance in the same time period. Allergies developed in adults also are more likely to persist even with strict avoidance. The mechanism by which tolerance develops is still unknown; however, those who do develop tolerance tend to have lower food-specific IgE at the time of diagnosis. It should be noted that the severity of food allergy reactions has not been correlated with size of SPT, level of specific IgE, or amount ingested resulting in allergic reaction. Cross-reaction seen in IgE testing between similar foods has been demonstrated, for example, legumes (i.e., peanut and soy) and milk (i.e., cow’s milk and goat’s milk). Table 16-2 lists several foods that may cross-react within a family and the likelihood of clinical significance.

Table 16-1 Food-Pollen Allergen Cross-Reactivity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 16-2 Food Allergen Cross-Reactivity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

V. ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic skin disorder that generally begins in early infancy and is characterized by typical distribution, extreme pruritus, chronically relapsing course, and association with asthma and allergic rhinitis. The disruption of the skin barrier may allow for increased sensitization, and most children will present with specific IgE to foods already tolerated in the diet. In well-controlled studies, about one-third of children with atopic dermatitis have food allergic reactions. As will be discussed below, a detailed dietary history may assist differentiation between sensitization and allergy.

VI. MIXED IgE-, NON-IgE-MEDIATED DISEASE

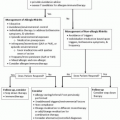

A. Eosinophilic esophagitis

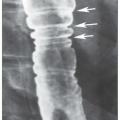

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) usually presents in childhood but has been seen increasingly in adults as well. Patients typically complain of vomiting, retrocardiac pain, and abdominal pain. Dysphagia is a common complaint, and food impaction has been observed in adults with EoE. Up to 70% of patients demonstrate food-specific IgE without symptoms of immediate food hypersensitivity. In addition to IgE production, expression of serum cytokines and inflammatory markers including COX-2, periostin, IL-5, IL-13, and eotaxin-3 attracts inflammatory lymphocytes and eosinophils. Current consensus requires an esophageal biopsy with the presence of >15 eosinophilic cells per high-powered field for diagnosis. Endoscopic evaluation may reveal longitudinal furrows, concentric rings, white exudates, mucosal edema, or esophageal narrowing, which are suggestive but not diagnostic of EoE disease. Resolution of symptoms and histologic changes following acid suppression with a proton pump-inhibiting medication may be seen in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease but not with EoE. Dietary therapy in children has shown some effectiveness when trigger foods are avoided. Strict elimination diets using amino acid-based formulas appear superior to food elimination based either on specific IgE testing or elimination of common food allergens. Repeat endoscopy is necessary to document resolution of tissue eosinophilia after elimination diet. Endoscopy may also be used following reintroduction of food to assess recurrence of EoE disease.

B. Non-IgE-mediated disease

The pathophysiology of non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity remains incomplete. The clinical presentation and history remains the key to diagnosis, with limited laboratory tests for confirmation. We discuss three of the more common presentations below.

C. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome

Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) is a relatively rare disorder of the GI tract identified in the pediatric patient. A recent study of 13,019 Israeli infants found an incidence of 0.34% (44/13,019), all with symptoms before 6 months of age. Milk or soy formula has been implicated in several cohorts; however, none of the Israeli infants reacted to either milk or soy. FPIES is thought to develop after stimulation of T cells by food protein, although the role of T cells in the disease remains unclear. Endoscopic biopsy

specimens may demonstrate patchy villous injury with prominent eosinophilic infiltration and colitis. Delayed onset of symptoms and lack of cutaneous manifestations often delays the diagnosis, subjecting children to repeated episodes, unnecessary testing, and occasionally invasive procedures. Fortunately, the diagnosis may be made clinically, and endoscopy is rarely indicated. The child classically presents at 3 to 7 months of age with profound vomiting about 2 hours after ingestion of an offending food protein, with or without diarrhea. Children may appear pale, cyanotic, or lethargic. Patients may present with a metabolic acidosis. Symptoms occur after each exposure to the triggering food. SPT and serum IgE to specific foods are negative. Rice has been the most commonly implicated solid food. Other triggering foods reported include wheat, oat, sweet potato, and banana. Avoidance of the triggering food protein leads to rapid resolution of symptoms. After 2 weeks of avoidance, an open feeding challenge may confirm the diagnosis. Caution during food challenges is warranted as some children experience more significant reactions after a period of avoidance. Treatment consists of complete avoidance of the triggering food, and tolerance develops in most children by 3 to 4 years of age.

specimens may demonstrate patchy villous injury with prominent eosinophilic infiltration and colitis. Delayed onset of symptoms and lack of cutaneous manifestations often delays the diagnosis, subjecting children to repeated episodes, unnecessary testing, and occasionally invasive procedures. Fortunately, the diagnosis may be made clinically, and endoscopy is rarely indicated. The child classically presents at 3 to 7 months of age with profound vomiting about 2 hours after ingestion of an offending food protein, with or without diarrhea. Children may appear pale, cyanotic, or lethargic. Patients may present with a metabolic acidosis. Symptoms occur after each exposure to the triggering food. SPT and serum IgE to specific foods are negative. Rice has been the most commonly implicated solid food. Other triggering foods reported include wheat, oat, sweet potato, and banana. Avoidance of the triggering food protein leads to rapid resolution of symptoms. After 2 weeks of avoidance, an open feeding challenge may confirm the diagnosis. Caution during food challenges is warranted as some children experience more significant reactions after a period of avoidance. Treatment consists of complete avoidance of the triggering food, and tolerance develops in most children by 3 to 4 years of age.

D. Allergic proctocolitis

Presenting in the first weeks to months of life, infants with allergic proctocolitis demonstrate normal development and weight gain but pass stools containing gross blood with or without mucus. As many as 60% of these infants are breast-fed, the remaining children receiving either cow’s milk or soy-based formula. The incidence of allergic proctocolitis has yet to be established; however, in one study of 22 infants with rectal bleeding, 14 (64%) were found to have allergic colitis on rectal biopsy. In cases where the diagnosis was in question, pathologic evaluation of tissue samples reveals an eosinophilic infiltration of the epithelium, lamina propria, and the muscularis of the distal colon, though biopsy is not recommended to establish the diagnosis. The elimination of milk or soy protein from the diet, either through maternal diet modification or use of a hydrolyzed infant formula, leads to resolution of symptoms within 24 to 72 hours. Specific IgE to milk or soy protein is typically not found in these infants. Most cases can be diagnosed with history and elimination diets, as with FPIES. After resolution of symptoms following an elimination diet, most children are able to tolerate a normal diet by 12 to 24 months of age.

E. Celiac disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree