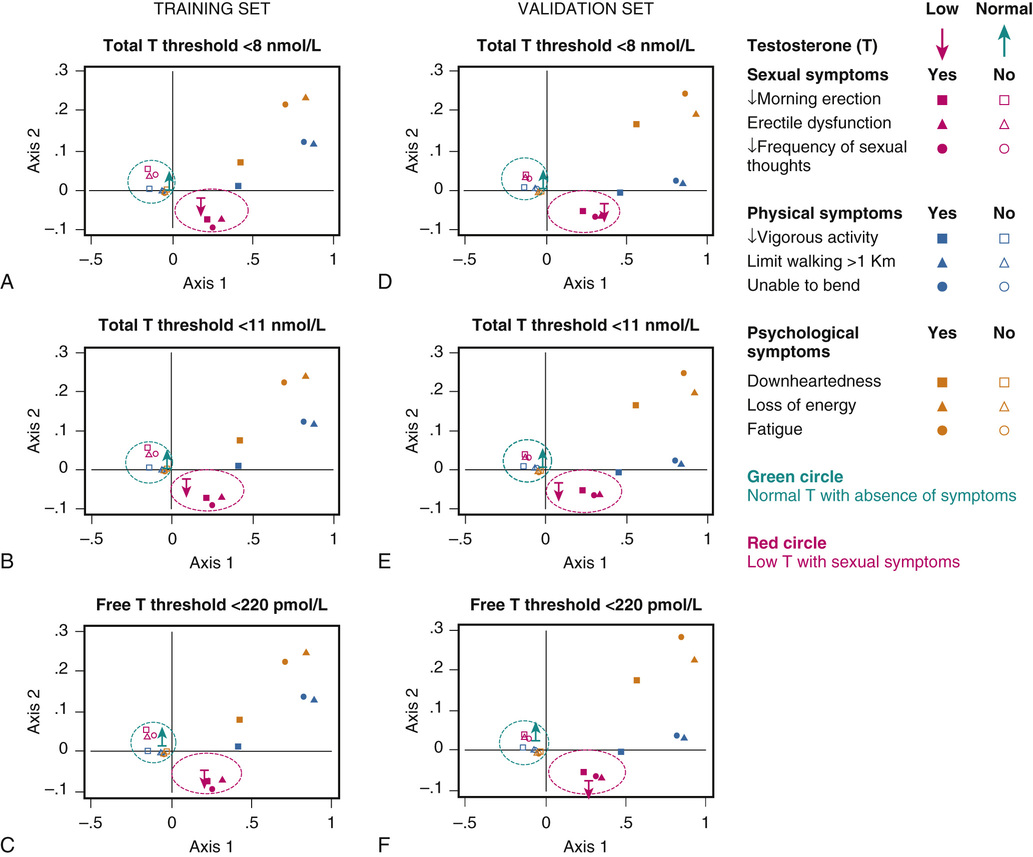

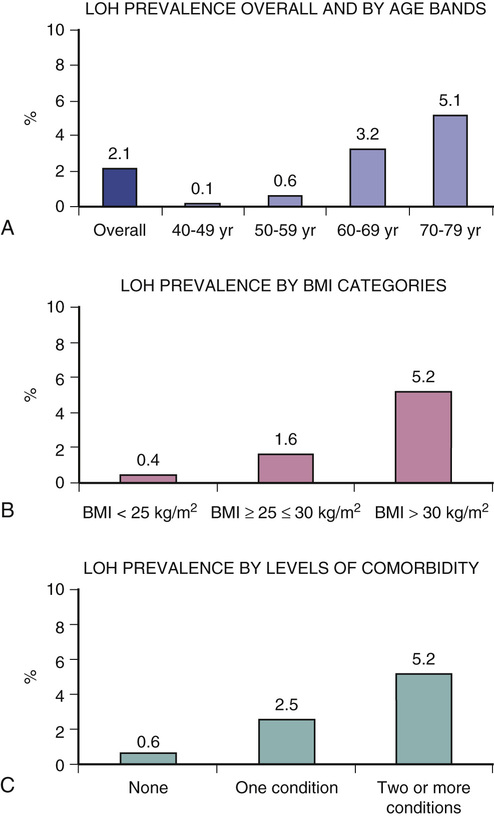

Frederick Wu, Tomas Ahern As men age, testosterone levels fall, leading to speculation that testosterone supplementation can ameliorate age-related deterioration in physical and psychological functions, health-related quality of life, and life span. Aging and hypogonadism share many clinical features. Age-related decrease in testosterone levels appears to be associated with a combination of the effects of aging on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis as well as an increasing prevalence of obesity and chronic illness. Testosterone levels fall below the threshold of normality in only a small minority of aging men. The effects of testosterone therapy for older symptomatic men with borderline low testosterone levels are the subject of much debate. Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of testosterone treatment showed inconsistent benefits, and safety concerns have led to intense scrutiny by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Whether testosterone therapy can improve age-related symptoms and deficits remains unclear, and the conflicting trial data make it challenging to provide a clear explanation of potential risks and benefits of testosterone therapy. Male hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome resulting from low testosterone concentrations and deficient spermatogenesis due to pathologic disruption of the HPG axis.1,2 The condition is usually categorized into primary or secondary hypogonadism caused by testicular or hypothalamic-pituitary disorders, respectively.3 Klinefelter syndrome is an example of primary hypogonadism that results from a congenital chromosomal aberration (mostly 47,XXY) and affects approximately 0.2% of male newborns.4 In addition to low testosterone levels and elevated gonadotropin levels (primary hypogonadism), men with Klinefelter syndrome have small testes and tend to have decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, poor beard growth, infertility (with azoospermia), tall stature, sparse pubic hair, gynecomastia, decreased muscle mass, decreased muscle strength, low bone mineral density (BMD), and anemia.4 In later life, men with Klinefelter syndrome are more likely to have decreased physical function, diabetes, obesity, bone fracture, and increased mortality.4 Hypopituitarism can cause secondary hypogonadism to arise after puberty. Causes include hypothalamic-pituitary tumor (e.g., prolactinoma or nonfunctioning adenoma), hypothalamic-pituitary infiltration (e.g., hemochromatosis), medications (e.g., glucocorticoids, opioid analgesics), brain insult (e.g., traumatic injury, irradiation), and chronic illness (e.g., diabetes and HIV infection).5 In addition to low testosterone levels and low gonadotropin levels (secondary hypogonadism), men with hypopituitarism after puberty tend to develop similar features to those of men with Klinefelter syndrome, with the exceptions of small penis size, poor beard growth, and abnormal height.5 Hypogonadism can result from disruption at more than one level of the HPG axis. Opioids, for example, bind to receptors in the hypothalamus6 and pituitary7 glands and inhibit secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone6 and luteinizing hormone (LH).7 In addition, opioids act directly on the testis to decrease production of sperm and testosterone.8 Similar to men with primary hypogonadism or secondary hypogonadism, men with hypogonadism caused by multilevel disruption experience adverse effects on multiple organ systems.6,9 One of the hallmarks of hypogonadism is an improvement in sexual function and body composition (increased BMD, increased fat mass, and decreased fat mass) in response to testosterone replacement therapy.10 In cases of pathologic hypogonadism (as described earlier), the efficacy and safety of testosterone replacement has been well established based on long-standing clinical experience.11,12 In the European Male Aging Study (EMAS), a population survey of 3369 community-dwelling men aged older than 40 years, total testosterone concentrations fell by 0.1 nmol/L (0.04%) per year and free (not protein bound) testosterone concentrations fell by 3.83 pmol/L (0.77%) per year.13 This led to subnormal testosterone levels being detected in a minority of aging men (free testosterone < 220 pmol/L in 12%, total testosterone < 10.5 nmol/L in 8%, and late-onset hypogonadism [see definition later in this chapter] in 1.3%). Both the EMAS and the Boston Area Community Health Survey (BACH) found that the prevalence of a total testosterone concentration below 10.5 nmol/L is between 16% and 26% of men aged 70 to 79 years compared to between 11% and 22% of men younger than 50 years.3,14 It is interesting that not all studies have observed lower testosterone levels in older men. Studies of healthy men describe no difference in testosterone concentrations between older and younger men,15 suggesting that ill health may contribute substantially to the apparent age-related testosterone decline. Aging leads to multilevel HPG axis disruption, which is influenced variably by body weight, acute or chronic illness, medications, and lifestyle. Testicular function declines with aging. Testicular volume of men older than 75 years is 31% smaller than that of men aged 18 to 40 years (20.6 mL vs. 29.7 mL).16 Leydig cell number is approximately 44% lower in men aged 50 to 76 years than in men aged 20 to 48 years.17 Congruently, the secretory capacity of the testes, in response to human chorionic gonadotropin or recombinant human LH, is substantially lower in older men than in younger men.18 Prospective longitudinal studies corroborate these mechanistic data and have found uniformly that LH concentrations rise with aging.19–22 Although declining testicular function appears to be the main mechanism underlying the age-related decrease in testosterone, decreased hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion can also contribute to the dysregulation in the HPG axis in older men.23 In addition, obesity plays a role in the fall in testosterone levels with aging. Fat mass increases with aging and peaks normally at 65 years.24 Testosterone concentrations are lower in obese men (BMI > 30 kg/m2) than in lean men (BMI 20-25 kg/m2), and obese men’s testosterone concentrations decline more quickly.13 Despite having lower testosterone concentrations than lean men, obese men do not have elevated LH concentrations; this finding suggests a hypothalamic-pituitary defect,2 which may be the result of elevated cytokine concentrations25 and/or insulin resistance.26 Chronic illness contributes also to the decline in testosterone levels with aging. Men with chronic illness have lower testosterone levels compared with healthy men.2 Like men with obesity, LH concentrations are not elevated in those with chronic illness; this finding suggests a hypothalamic-pituitary defect.2 Chronic illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM 2), are associated with increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines,27 which, as with obesity, may disrupt the hypothalamus, resulting in lower testosterone levels.25 Frailty (represented as either a physical syndrome or a health status index) is associated with lower free testosterone and higher LH, suggesting activation of functional reserve in the HPG axis to compensate for impaired testicular function.28 Statin use29 and vitamin D deficiency30 have also been reported to be associated with lower testosterone levels in older men. In the EMAS, men with low testosterone levels, in the absence of a disease or medication known to affect the HPG axis, had higher BMI, lower muscle mass, lower BMD, higher glucose levels, lower hemoglobin levels, slower walk speeds, and greater illness prevalence compared to men with normal testosterone levels.31 These features associate only weakly with testosterone levels, however, and are mimicked by chronic illness and the aging process. With the exception of glucose and hemoglobin, no statistically significant relationships persisted after adjustment for age, BMI, and chronic illness. The Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) found that the prevalence of loss of libido increased, over the course of 9 years, from 30.6% to 41.1% and that the prevalence of erectile dysfunction increased from 37.4% to 42.3%.32 Counterintuitively, symptoms of hypogonadism have poor predictive value for low testosterone concentrations and vice versa.3,14 The BACH study showed that of men older than 50 years, only 20.2% of those with symptoms of hypogonadism had a low total testosterone level (≤10.5 nmol/L) and of men with a low testosterone level, only 20.1% reported low libido and only 29.0% reported erectile dysfunction.14 These findings highlight the significant overlap between symptoms of hypogonadism and aging, which have relatively poor specificity for low testosterone levels. EMAS investigators tried to surmount these issues by defining late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) as the presence of three sexual symptoms (decreased frequency of morning erection, decreased frequency of sexual thoughts, and erectile dysfunction) together with a total testosterone concentration less than 11 nmol/L and a free testosterone concentration less than 220 pmol/L (Figure 84-1).1 This syndrome affects approximately 3% of men aged 60 to 69 years and approximately 0.1% of men aged 40 to 49 years (Figure 84-2).1 During the 4.3-year follow-up, nearly 1.5% of eugonadal men developed LOH, and of men with LOH at baseline, nearly 30% recovered. Thus, LOH is not invariably persistent and clinical management strategies need to take this into account. International guidelines recommend that a testosterone level that is below the 2.5 percentile in young, healthy adult men be used to define the threshold for a low testosterone level.11,12 The incidence of depressive illness is greater in men with low testosterone levels.33 Low testosterone confers also an increased likelihood for the development of poor physical function34 and frailty,35 although this relationship becomes nonsignificant after adjustment for chronic illness.35,36 DM 2 incidence and cardiovascular disease prevalence are also higher in men with low testosterone levels than in men with normal testosterone levels.37,38 Similarly, men who have undergone androgen deprivation therapy, to effect severe hypogonadism as part of treatment for advanced prostate cancer, have an increased risk of developing diabetes and/or myocardial infarction and have increased mortality.39 Men with low testosterone levels caused by a disease of the HPG axis usually have testosterone levels that are well below the threshold described previously in this chapter.40,41 Men with age-related low testosterone levels, however, tend to have testosterone levels that are just below this range.3 As described earlier, aging, obesity, and chronic illness contribute to the development of age-related low testosterone levels, and these (and perhaps other factors) may be the reason for adverse consequences and not the low testosterone level per se. This is illustrated by prospective studies that found that once the data were adjusted for obesity and chronic illness, age-related low testosterone levels were not associated with increased mortality42 unless a very low testosterone threshold (<8.36 nmol/L) was used.43 The situation differs for men at the upper extreme of age (older than 70 years): some studies have shown an association between low testosterone levels with increased mortality and some have not.44 EMAS data showed an association between sexual symptoms and mortality that was independent of testosterone levels.43 In the United States, the number of men who received a prescription for testosterone increased from 1.3 million in 2010 to 2.3 million in 2013, with approximately 70% of these aged between 40 and 64 years, approximately 15% aged 65 through 74 years, and approximately 5% older than 75 years.45 A multinational survey of testosterone prescribing found that between 2000 and 2011, global sales of testosterone sales increased 12-fold from 115 million to 1.4 billion U.S. dollars.46 Current guidelines of international endocrine societies recommend use of testosterone therapy for men with aging-related hypogonadism provided that testosterone levels are confirmed to be low, the patient has features consistent with hypogonadism, and appropriate screening for disease of the HPG axis is performed.11,12 These guidelines state also that two consecutive testosterone measurements are required to confirm the presence of low testosterone since the difference between two testosterone measurements on the same person exceeds 20% about half the time.47 Because of significant diurnal variation in testosterone levels and the considerable effect of food intake on decreasing testosterone levels (by ≈25%), blood for determination of testosterone levels should be taken in the early morning and in the fasting state.48 It should be noted, however, that the FDA, in contrast to these guidelines, does not consider a low testosterone level due to aging alone an indication for testosterone therapy.49 Remediable causes of hypogonadism can be treated specifically by therapies other than testosterone. Dopamine agonist therapy will increase testosterone levels in men with hyperprolactinemia,50 as will bariatric surgery for men with DM 2, severe obesity, or both.51 For men with less severe obesity, diet and exercise increases testosterone levels.52 For men with a low testosterone level and non-elevated LH levels (secondary hypogonadism) who desire fertility, consideration should be given to antiestrogen,53 aromatase inhibitor,54 gonadotropin therapy,55 and/or pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone therapy. The use of aromatase inhibitor therapy, however, is not widely endorsed because long-term safety data are lacking. An increasing number of preparations are currently available for testosterone replacement therapy.56 Transdermal and buccal formulations of testosterone therapy require daily administration, whereas intramuscular testosterone ester preparations are given every 3 to 14 weeks. Oral testosterone and 17α-alkylated androgen preparations are not recommended because of potential liver toxicity and variable clinical response. The dose of testosterone therapy should be titrated to maintain a predose testosterone level in the middle to lower part of the normal reference range. More detailed recommendations on the practical aspects of testosterone therapy are available in published guidelines.11,12

Aging Males and Testosterone

Introduction

Male Hypogonadism

Age-Related Decrease in Testosterone Levels

Other Factors Related to Decrease in Testosterone Levels

Age-Related Low Testosterone Levels and Hypogonadism

Late-Onset Hypogonadism

Adverse Effects of Low Testosterone Levels

Mortality and Testosterone Levels

Testosterone Therapy

Prescription Trends

Considerations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Aging Males and Testosterone

84