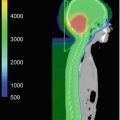

Fig. 36.1

The Hebrew Letter Bet

36.8 The Second Problem: The Problem of the Physician’s “License to Heal”

For a person who believes that we live in a world governed by an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-just, and all-merciful monotheistic G-d, then all of life’s events and the natural world are part of the Divine will. CNS malignancies, therefore, as a natural event, may also be construed as part of the Divine will. Some people of faith, therefore, conclude that human interference with illness is, at best, hubris and, at worst, a direct attempt to interfere with Divine will and, therefore, blasphemous. By what right can a physician presume to try and effect the course of a fellow human’s illness against the deliberate designs of Providence? (Jakobovits 1959) This concept is referred to as either “the right to heal” or “the license to heal.”

The problem of the alleged defiance of the will of G-d does not, of course, only apply to the physician’s license to heal. Consider, for example, the lightning rod. By the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, many people had observed lightning and its destructive capabilities. Trees and buildings were felled and/or burned and animals and humans were killed or injured by lightning strikes. To many observers at the time the destruction wrought by lightning must be caused by G-d’s wrath directed against humans for their misdeeds (Dray 2005).

To the modern reader, explaining lightning or disease or, for that matter, earthquakes and floods as the punishment of a wrathful G-d might seem strange. However, to our forebears these events seemed to make sense if they were attributed either to a wrathful G-d or to a battle between the forces of G-d and Satan. Rather than the world being one of complete moral chaos, the world could be at least be understood in terms of either Divine punishment or Divine v. Satanical combat.

When understood in the context of his times, therefore, it is not surprising that Benjamin Franklin’s invention and implementation of lightning rods as a means of protecting people and property was viewed, by many of his contemporaries, as interfering with the Will of G-d. By what right did a mere human aspire to snatch lightning from the heavens and transmit it, via a grounded electrical conducting cable, to the earth? Some Christian ministers of Franklin’s time attributed other natural disasters such as earthquakes as Divine punishment for Franklin’s invention. On the other hand, many others lauded Franklin for his use of observation and reason to understand and address the problem of lightning strikes (Dray 2005).

Using human reason to treat childhood brain tumors or inventing the lightning rod raise similar theological questions and have been debated on analogous terms. Societal attitudes toward the ill person have gone through several phases in the Western heritage. Among ancient Semitic civilizations, the ill person was burdened with an odium insofar as some people felt that illness was an atonement for unrighteousness. In Ancient Greece, illness destroyed the idea of the perfect harmony and balance of health (Jakobovits 1959). With the rise of Christianity, suffering assumed the character of purification and a mean of achieving grace. Martyrdom was redemptive.

There are three major approaches taken to deal with the theological problem of the physician’s license to heal. One is to reject medicine altogether. Suffering is to be borne. Any attempt to ameliorate and treat disease is an attack on the Divine scheme of life. Sir William Osler, in his 1913 series of lectures later collected in the book The Evolution of Modern Medicine, seeks to explain why, after the fall of the Roman Empire, “the light of [medical] learning burned low, flickering almost to extinction. How came it possible that the gifts of Athens and Alexandria were deliberately thrown away?” (Osler 1921) Osler lays some of the blame on the collective societal trauma of the destruction of Rome and the devastating effects of the plague. He places, however, considerable blame on medieval Christianity’s position on the question of the license to heal. Consider, Osler writes, the change wrought by Christianity.

The brotherhood of man, the care of the body, the gospel of practical virtues formed the essence of the teaching of the Founder—in these the Kingdom of Heaven was to be sought; in these lay salvation. But the world was very evil, all thought that the times were waxing late, and into men’s minds entered as never before a conviction of the importance of the four last things—death, judgment, heaven and hell. One obstacle alone stood between man and his redemption, the vile body, “this muddy vesture of decay,” that so grossly wrapped his soul…the wisdom of the Greeks was not simply foolishness, but a stumbling block in the path. Knowledge other than that which made a man “wise unto salvation” was useless. All that was necessary was contained in the Bible or taught by the Church…The new dispensation made any other superfluous. As Tertullian said: Investigation since the Gospel is no longer necessary. (Dannemann, Die Naturw., I, p. 214.) This attitude of the early Fathers toward the body is well expressed by [Saint] Jerome. “Does your skin roughen without baths? Who is once washed in the blood of Christ needs not wash again.” In this unfavorable medium for its growth, science was simply disregarded, not in any hostile spirit, but as unnecessary. (Osler 1921)

A second approach to the problem of the license to heal is to ask: Is there any less moral justification for curing illness by the use of human intelligence than there is for using human intelligence to derive methods for irrigating the soil to improve crop yields or to put a roof over one’s head? Maimonides, for example, responds to people who think that one can restore a person’s faith by reducing their reliance on human cures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree