Primary hypogonadism occurs in both types of APS, and ovarian failure is more frequent than testicular failure.

Tuberculosis is the second most common cause of ‘Addison’s disease’. Rarer causes of adrenal insufficiency are listed in Box 6.1.

The adrenal glands are a relatively common site of metastases. However, adrenal insufficiency with metastases is much less common.

Adrenoleukodystrophy is a rare X-linked disorder, caused by mutations in the ABCD1 gene that result in the prevention of normal transport of very long chain fatty acids into peroxisomes (for beta-oxidation) and their accumulation in the central nervous system and adrenal cortex. Patients may present in childhood with increasing cognitive and behavioural abnormalities, blindness and the development of quadriparesis.

Adrenoleukodystrophy consists of a spectrum of phenotypes that includes adrenomyeloneuropathy. Adrenomyeloneuropathy typically presents in adult males between 20 and 40 years of age with adrenal insufficiency, spastic paraparesis, abnormal sphincter control or cerebellar signs.

For causes of secondary adrenal insufficiency see Chapter 12.

Chronic glucocorticoid use and HPA axis suppression

The following groups of patients are likely to have adrenal insufficiency secondary to HPA axis suppression by long-term glucocorticoid use:

- those who have received a glucocorticoid dose equivalent to or more than 20 mg of prednisolone per day for more than 3 weeks

- those who have received an evening or bedtime dose of prednisone for more than a few weeks

- those who have a Cushingoid appearance.

Clinical presentations of primary adrenal insufficiency

The insidious onset and non-specific symptoms usually result in a delay in diagnosis. Adrenal insufficiency may therefore be undetected until an acute illness or other stress precipitates an adrenal crisis.

Patients may have symptoms and signs of glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid and, in women, androgen deficiency. Patients with secondary adrenal insufficiency usually have normal mineralocorticoid function as mineralocorticoids are regulated by the renin–angiotensin system rather than adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH).

Clinical presentations of primary adrenal insufficiency are summarized in Box 6.2.

Adrenal crisis

Adrenal crisis most commonly presents as shock. Acute adrenal crisis may be seen in patients with:

- previously undiagnosed adrenal insufficiency who have been subject to acute stress or illness, for example infection

- known adrenal insufficiency who have not increased their steroid dose during an infection or other illness, or have been vomiting

- those with HPA suppression caused by the long-term use of glucocorticoids (oral and occasionally inhaled) who suddenly stop their treatment

- bilateral adrenal infarction or haemorrhage

- pituitary apoplexy (infarction) resulting in acute cortisol deficiency.

General

Patients with adrenal insufficiency often have non-specific symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, lethargy, weakness, anorexia and weight loss.

Gastrointestinal

Patients may complain of nausea, occasionally vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea that may alternate with constipation. The cause of gastrointestinal symptoms in adrenal insufficiency is not fully understood but may be related to electrolyte abnormalities.

Hypotension

Adrenal insufficiency can present with postural hypotension (causing postural dizziness), low blood pressure or improved blood pressure in patients with pre-existing hypertension. This is mainly due to volume depletion resulting from aldosterone deficiency. Glucocorticoid deficiency can contribute to hypotension by causing decreased vascular responsiveness to the vasoconstrictor effect of nor-adrenaline and angiotensin II.

Skin

In primary adrenal insufficiency, lack of cortisol negative feedback causes an increase in the hypothalamic precursor protein proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and its cleavage products, including ACTH and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone. The latter increases the melanin content of the skin, resulting in hyperpigmentation.

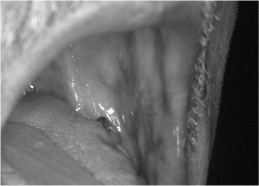

Hyperpigmentation may be generalized, particularly in areas exposed to light or pressure (e.g. elbows, knees, spine, knuckles, brassiere straps). It may also be seen in the palmar creases, nails (longitudinal bands of darkening), buccal mucosa (Fig. 6.1) and scars acquired when primary adrenal insufficiency is present and untreated. The hyperpigmentation usually disappears after a few months of treatment with glucocorticoids. However, scars never fade because the melanin is trapped in fibrous connective tissue.

Figure 6.1 Buccal pigmentation in a patient with Addison’s disease.

Associated vitiligo (areas of depigmented skin) is seen in 10–20% of patients with Addison’s disease. Vitiligo results from autoimmune destruction of dermal melanocytes.

Electrolyte abnormalities

Hyponatraemia is seen in 90% of patients and is due to sodium loss caused by mineralocorticoid deficiency, and increased antidiuretic hormone secretion caused by cortisol deficiency (resulting in reduced renal water clearance). Patients may present with salt craving.

Hyperkalaemia occurs in 60% of patients. It is associated with mild hyperchloraemic acidosis and is due to mineralocorticoid deficiency.

Patients may have an elevated urea (and possibly creatinine) due to dehydration. Hypercalcaemia may rarely occur in Addison’s disease.

Hypoglycaemia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree