Adolescent and Young Adult Pregnancy and Parenting

Joanne E. Cox

Madeline Beauregard

KEY WORDS

Abortion

Contraception

Medical home

Parenting

Pregnancy

Prenatal care

Unplanned

Although adolescent and young adult (AYA) pregnancy rates have declined by more than 50% and 25% respectively since a peak year in 1991, many more young people experience unplanned pregnancy in the US than in other industrialized countries.1,2 Over 80% of teen pregnancies and 70% of pregnancies to unmarried women aged 20 to 24 years are unplanned.3 Unplanned pregnancies are prevalent especially in AYAs who are Black or Hispanic, low-income and in those who have not completed high school. In 2008, there were 620,000 unplanned pregnancies in teens 15 to 19 years old, whereas women aged 20 to 24 years experienced 1,080,000 unplanned pregnancies, resulting in considerable public cost.3

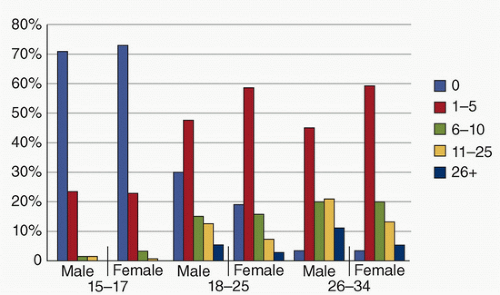

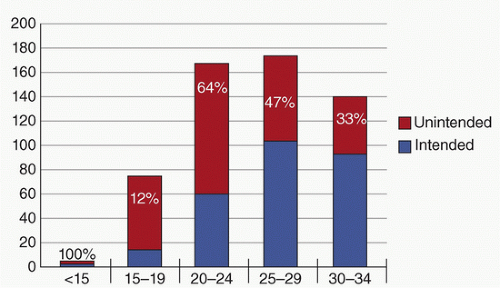

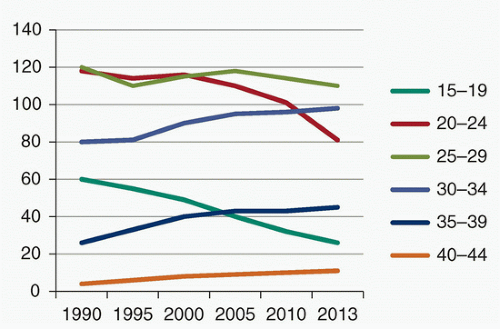

There are significant trends in comparing AYA pregnancy and birth rates (see Figs. 40.1,40.2 and 40.3).

Pregnancy rates: Pregnancy rates increase with age up through age 29 (Figs. 40.1 and 40.2). The percentage of pregnancies that end in births also increases with age, while the percentage ending in abortions decreases and miscarriages remain fairly constant (Fig. 40.2).

Intention: The percentage of total pregnancies that are unintended decreases with age (Fig. 40.1). Despite the rates of unintended pregnancies being highest in women aged 20 to 24, this comprises 64% of all pregnancies in comparison to 82% in the 15 to 19 age-group.

Birth rates trends: In 2013, teen birth rates reached a nadir of 26.6 per 1,000 girls aged 15 to 19 years, compared to 81.2 per 1,000 women aged 20 to 24 years in 2013.1 Trends show a decrease of birth rates in AYAs until age 29 years, with rates rising over time in those aged 30 years and over (Fig. 40.3).

Variables that affect AYA birth rates include ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. Over the last 15 years, Hispanic teens have had the highest rate of teen births.1 Teen birth rates also vary considerably by state. In 2012, New Mexico had the highest teenage birth rate at 47.5 per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 years. This compares to New Hampshire, with the lowest teenage birth rate at 13.8 per 1,000 females aged 15 to 19 years. From another perspective, by 2012, the teen birth rate in California had decreased by 64% since 1991. Comparatively, the teen birth rate in West Virginia has seen the smallest decline since 1991, with a 24% change since 1991.3

College students: Among college-age students who reported having vaginal intercourse, 1.4% of females had experienced unintended pregnancy in the last year and 1.5% of males reported impregnating their partner.4

Poverty

Poverty is the strongest factor associated with unplanned AYA pregnancy. Recent evidence suggests that both long-term exposure to poverty and living in impoverished neighborhoods during adolescence independently increase the risk of adolescent and unplanned pregnancy.5 For AYAs, living in poverty may be associated with lack of hope for the present and future that translates into overall risky behaviors and lack of attention for the consequences. A baby can represent success and hope for the future for AYAs faced with economic and educational obstacles.

Rates of Sexual Activity

While there has been a decline in lifetime report of sexual activity, 15- to 19-year-old prevalence rates are 60.6% for Blacks, 49.2% for Hispanics, and 43.7% for Whites.6 Males are slightly more likely to be sexually experienced than females; and, sexual activity increases with grade, among ninth through twelfth graders.

Physical and Sexual Abuse

Abusive relationships are common features in the lives of AYA mothers. Adolescents with a history of child abuse or neglect are twice as likely to experience early pregnancy, and those with histories of sexual abuse or neglect are at highest risk.7 Those who have been sexually abused often become preoccupied by sexualized thoughts and become sexually active early, leading to risk of pregnancy. Reproductive coercion by male partners is also a potential risk factor.

Cultural and Family Values

Many AYAs live in communities familiar with early parenthood; so they are less likely to postpone sexual intercourse. Adolescents living in families with little parental support, little restriction of risky behaviors, and poorly defined goals are more likely to become sexually active and likewise to become adolescent parents. Other cultural factors that may play a role in decisions to become pregnant include peer pressure, early dating, and lack of religious affiliation. Although more adolescents have delayed pregnancy, they often experience unplanned pregnancy as young adults.

Early initiation of sexual activity is not unusual if other family members have a prior history of becoming pregnant during adolescence. Adolescent parents may have mothers, sisters, or brothers who were teen parents. Pregnancy can result in both joy or excitement and increased stress, which potentially either increases or decreases a sibling’s risk of pregnancy.8

Psychological

Mental health problems such as depression may influence a young woman’s decision to become pregnant. Pregnant and parenting young people have high rates of depression, but they also often have poor social supports and conflicted relationships while living in low-income, violence prone neighborhoods, all of which predispose them to mental health disorders.9 Other risky behaviors are associated with concomitant sexual activity including alcohol and drug use.6

Early Puberty and Development

Since 1900, the average age at onset of menarche has significantly decreased. This earlier physical maturation has widened the gap between reproductive capacity and cognitive and emotional maturation and has increased the risk of unintended pregnancy in this age-group.

Many developmental characteristics of adolescents, particularly of younger teens, interfere with decision making regarding sexual activity and the successful use of contraceptives. These include a limited ability to plan for the future or to foresee the consequences of their actions and a sense of personal invulnerability.

Media

Exposure to highly sexualized media has long been considered a risk factor for AYA unplanned pregnancy. This was especially true in the US, where the sexualized medial culture seemed at odds with a national focus on abstinence education and restriction on contraceptive availability. However, the popular 16 and Pregnant and Teen Mom shows may have reversed that association. Data have suggested that some of the pregnancy decline is the result of accurately reporting the reality of pregnancy and parenting at a young age.10

Access to and Adherence with Contraception

Obtaining and adhering to contraceptives remains critical to minimizing the number of unplanned AYA pregnancies. In 2011, about 11% of male high school students and 15% of female high school students did not use any method to prevent pregnancy during their most recent sexual intercourse. Among those who did use some method of contraception, the condom was most popular. About 67% of males and 54% of females used a condom during their most recent sexual intercourse. About 13% of males and 23% of females used a birth control pill during their most recent sexual intercourse.6

Although lack of negative attitudes toward pregnancy may be a factor in failure to use contraception, access to confidential counseling and prescriptions is also important. AYAs who feel that pregnancy will inhibit their career or educational goals are more likely to comply with contraception.11 Yet, access remains problematic. In a recent study, half of adolescents reported not using contraception prior to an unplanned birth; and lack of access to contraception was associated with unplanned births.11

Many environmental, social, and psychological barriers interfere with decision making regarding sexual activity and contraception among AYAs. Significant obstacles to successful contraception include inaccurate information, accessibility, contraceptive acceptability, and partner issues (see Chapter 41). Some young women chose not to protect themselves from pregnancy because they desire to have a baby. AYAs may experience barriers to acquiring contraception from their health providers. Providers may not address sexuality and contraception use, and patients may be embarrassed to initiate the discussion. Some clinicians may be overtly judgmental of sexuality and contraception. Providers may be unwilling to provide contraception to AYAs without parent consent. Clinicians may be unnecessarily concerned about safety of contraceptives, especially long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods such as the intrauterine device (IUD) (see Chapter 44).12

Repeat teen birth has decreased in number over the past 2 decades, but accounts for 18.3% of total births to teen mothers. Low-income, non-White adolescents experience a disproportionate number of repeat births.13 Repeat pregnancy has adverse effects on parenting

while increasing stress and reducing maternal economic and educational outcomes. Inconsistent contraceptive use and high-risk sexual activity are known predictors of repeat pregnancy. LARC has demonstrated efficacy in preventing repeat pregnancies.14,15

while increasing stress and reducing maternal economic and educational outcomes. Inconsistent contraceptive use and high-risk sexual activity are known predictors of repeat pregnancy. LARC has demonstrated efficacy in preventing repeat pregnancies.14,15

Multiple interventions have been tested to decrease repeat pregnancy. Teen-tot medical homes, motivational interviewing, and home-visiting show promise.16,17 AYA mothers with strong sense of both control over their contraceptive decision making and intent to prevent pregnancy are most likely to avoid rapid repeat pregnancy.

Many adolescent pregnancy prevention interventions have been implemented and studied over the last 2 decades. They generally fall into three categories: (1) clinic-based models with emphasis on counseling and access to contraception, (2) school-based abstinence-only and comprehensive educational programs, and (3) school-linked community programs.18

Program designs are varied and may be developed by parents, schools, physicians, religious groups, social agencies, and/or government departments. Successful programs include elements of abstinence promotion, contraceptive information/availability, sexual education, school completion strategies, job training, and other youth development strategies such as volunteerism, involvement in the arts or sports. Components of successful programs should be based on the age and developmental stage of the target group. A randomized controlled trial of abstinence-only education for 6th and 7th graders showed reduction in sexual initiation rates by 9th grade.19 However, abstinence-only programs for high school students have been associated with increased unprotected sexual activity.20

Research strongly supports a two-pronged approach to primary prevention by using methods to delay sexual initiation and by providing contraceptive education and availability, if necessary. No research exists that links contraceptive education with increased sexual activity.

When an adolescent or young adult presents to a health care facility for reproductive health services or advice, it is important to provide an environment that is welcoming, comfortable, and confidential.

Role of the Practitioner

Determining whether a pregnancy is intentional or unintentional is imperative in planning the management of the pregnancy. Both the age of the mother and her intentions behind the pregnancy may significantly affect the management of the pregnancy. Unplanned pregnancy can be a crisis for the young woman and her family. The provider is uniquely positioned to offer guidance and support.

Pregnancy requires that the provider gives balanced attention to the pregnant patient’s medical issues and her counseling needs. The young woman should be granted confidentiality as they discuss choices and plans. It is vital that the practitioner be familiar with their local laws on adolescent confidentiality as they vary geographically. In ideal circumstances, the AYAs’ family and her partner need to be considered as a plan is formulated to manage the pregnancy. However, the practitioner must ascertain whether there has been sexual coercion, history of physical abuse, as well as whether the potential for abuse exists. Opportunities for intervention include the following:

Diagnosis of pregnancy and facilitated decision making

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree