Adjuvant therapy is commonly used in melanoma because recurrence after surgery usually results in the patient’s eventual death. Surgeons have a profound influence on patients’ decisions regarding adjuvant therapy, beginning with providing a clear understanding of the risk of specific types of recurrence. This review summarizes the potential oncologic benefits and relevant toxicities of adjuvant systemic therapies for melanoma that are currently available and under investigation.

Adjuvant therapy is defined as treatment administered to patients who are clinically free of disease but at substantive risk of recurrence. In most tumor types, adjuvant therapy is preferentially used for patients at relatively high risk of recurrence in whom that recurrence would be difficult to treat or cure. There are 3 potential oncologic advantages a percentage of treated patients may derive from effective adjuvant therapy: (1) reduction in the risk of recurrence; (2) delay in the time to clinically evident recurrence, resulting in an increase in the time patients perceive themselves to be disease free; and (3) increase in the cure rate (overall survival) by administering therapy early in the course of disease when it is able to completely eradicate minimal residual disease that would have become incurable by the time it was clinically evident. There is one additional advantage all patients derive from adjuvant therapy, namely the sense of actively combating their disease rather than passively waiting for it to recur, often described as a feeling “I’ve done everything I could to beat this cancer.” In exchange for these potential or real advantages, all patients accept the toxicities of adjuvant therapy—including those patients whose disease was actually cured by the initial surgery.

Recurrent melanoma, whether in a regional nodal basin, confined to a single extremity as in-transit metastases, or disseminated throughout the body, is notoriously difficult to treat effectively and usually presages the patient’s ultimate demise. Melanoma patients who perceive themselves at risk of recurrence, therefore, are often very motivated to pursue adjuvant therapy with even a small chance of delaying or preventing recurrence. Surgeons have a profound influence on patients’ decision making regarding adjuvant therapy, beginning with providing a clear understanding of the risk of specific types of recurrence (local, regional nodal, in-transit, and distant). Surgeons also have an important role in explaining the morbidity of surgical treatment with and without adjuvant therapy, and of course they are instrumental in initiating the referral process to medical and radiation oncologists for consideration of specific adjuvant therapies.

Risk assessment in melanoma

Lymph Node Status as a Predictor of Distant Metastasis

In this era of “personalized medicine,” it is worth emphasizing that the surgical treatment and staging of melanoma has been highly individualized for many years. Sentinel node biopsy is a widely used staging procedure, intended to assess the risk of subsequent metastasis and death from melanoma. Patients with clinically or radiographically evident nodal metastasis, whether at the time of initial diagnosis or as a recurrence after prior wide excision of the primary are more likely to relapse and die than those with a “microscopic” metastasis. (By definition in the American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] staging system, any nodal metastasis discovered by sentinel node biopsy is a “micrometastasis” whereas any discovered clinically or radiographically is a “macrometastasis”.) Regardless of how nodal metastases present, radical lymphadenectomy is associated with cure in up to half of patients, and so aggressive surgical therapy is an important part of the management of any stage III melanoma. In addition to “tumor burden” (micrometastasis vs macrometastasis), as the number of lymph nodes involved by melanoma increases, the risk of distant metastasis and death also increases. Of note, even after nodal metastasis has occurred there is still prognostic information to be gained by knowing the thickness and ulceration status of the primary tumor.

At the present time, all patients with stage III melanoma are considered appropriate candidates for radical lymphadenectomy and, if they are otherwise healthy, consideration of adjuvant therapy. There is considerable interest in trying to identify a subset of node-positive patients who may be at very low risk for regional or distant recurrence, presumably those with very small tumor deposits in the regional nodes (“micrometastases” in a different sense of the word than the AJCC employs). To date, however, a threshold below which the risk of further recurrence in the regional basin and beyond is low enough to safely allow observation of the patient without either lymphadenectomy or adjuvant therapy has not been defined, but prospective trials are ongoing.

Lymph Node Status as a Predictor of Regional Recurrence

While a subset of “low-risk” stage III melanoma patients who do not require lymphadenectomy may eventually be defined, currently many patients have “high-risk” stage III disease at risk of recurrence in the nodal basin despite radical node dissections. Available evidence suggests that radiation can decrease the risk of recurrence after lymphadenectomy, but controversy remains regarding which patients are at sufficient risk of regional recurrence to possibly warrant radiation, as well as whether adjuvant radiation should be used in these patients following lymphadenectomy or be reserved only for the subset of patients with regional recurrence who can be re-resected to a disease-free state. To date, the presence of very large tumor-containing nodes or multiple involved lymph nodes and the finding of invasion of melanoma through the lymph node capsule into the surrounding tissue (extracapsular extension) are the most established indicators of increased risk of regional recurrence after lymphadenectomy, and are the most commonly employed criteria used to select patients for adjuvant nodal basin irradiation. Further discussion of adjuvant radiation in melanoma is provided in an article by Rao and colleagues elsewhere in this issue.

Risk of Recurrence After Resection of Oligometastatic Melanoma

In recent years, patients with one or a few distant metastases have increasingly been considered for surgical management. The combination of improved perioperative care combined with more effective imaging techniques has increased enthusiasm for this approach, and it is clear that some patients with resected stage IV disease have a prolonged disease-free interval after metastasectomy and a favorable overall outcome compared with patients with unresectable stage IV melanoma. At present, however, most patients recur relatively quickly after metastasectomy, and the prognostic factors associated with long-term recurrence-free survival for resected stage IV melanoma are not well defined. Clinical factors that appear to be most strongly associated with a short recurrence-free interval after metastasectomy are visceral metastatic disease (particularly liver metastases), multiple metastases and particularly multiple sites of metastasis, a rapid tumor doubling time as assessed radiographically, and a short disease-free interval between resection of the primary and development of stage IV disease. Nonetheless, given the overall high risk of recurrence after metastasectomy in melanoma and the absence of defined standard adjuvant therapy for this group, the authors consider all resected stage IV melanoma patients to be appropriate candidates for investigational trials of adjuvant therapy.

Adjuvant systemic therapy to reduce disease recurrence and death

Lack of Efficacy of Chemotherapy and Nonspecific Immunotherapies

Over the past 40 years, more than 100 randomized clinical trials have investigated cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents and nonspecific immunostimulants such as bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), Corynebacterium parvum , and levamisole. Despite the fact that statistically one would expect 1 clinical trial in 20 using ineffective therapy to yield a false-positive result, none of these trials were positive. Interest in nonspecific immunotherapy declined as more active immunostimulatory cytokines, in particular interferon (IFN), came into clinical practice.

Adjuvant Immunotherapy with Interferon

Interferon α-2b (IFNα-2b) is the only adjuvant regimen approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with stage IIB and stage III melanoma, and is considered the standard of care for these patients in the United States. Here the authors review clinical trials addressing the benefit of adjuvant IFN and discuss the controversies of these trials.

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) trial E1684 was the first randomized, placebo-controlled study of high-dose IFNα-2b (HDI), involving 287 patients with stage IIB (n = 31) or stage III melanoma. HDI was administered as 20 million units (MU) per m 2 intravenously 5 days per week for 1 month followed by 10 MU/m 2 subcutaneously 3 times per week for 48 weeks. At initial publication, after a median follow-up time of 6.9 years, relapse-free survival (RFS) was increased from 1.0 to 1.7 years and overall survival (OS) was increased from 2.8 to 3.8 years, both of which were statistically significant. Updated results after a median follow-up of 12.6 years showed the RFS benefit to have been maintained, but the statistical significance of the survival benefit had been lost. The diminished survival benefit after longer follow-up was of uncertain cause, but led many physicians to question whether HDI was worth the significant side effects.

The next cooperative group trial of IFN only increased the uncertainty about adjuvant therapy in melanoma. ECOG trial E1690 accrued 642 patients to a 3-arm study comparing HDI (n = 215) with low-dose IFN (LDI; 3 MU 3 times per week for 2 years, n = 215) and with observation (n = 212). HDI showed an improvement in RFS (44% relapse-free at 5-years) compared with LDI and observation (40% and 35%, respectively). However, unlike E1684, there was no OS benefit seen with either HDI or LDI compared with observation. Because HDI was approved by the FDA during the conduct of this trial, and patients with thick melanomas were allowed to enter the trial without any nodal staging or dissection, crossover of observation-arm patients to HDI after nodal relapse was a confounding factor that may have affected the survival results. This factor emphasizes the important role that surgical staging can play in adjuvant therapy trials and clinical decisions.

A third study, trial E1694, accrued 880 patients and compared an investigational ganglioside vaccine with HDI. HDI demonstrated a statistically significant benefit compared with the vaccine in RFS and OS. This result raised the question of whether HDI led to benefit or the vaccine caused harm, a question that has gained additional credence after a randomized trial of the same vaccine compared with observation in patients with stage II melanoma was stopped early because of a possible decrease in survival for vaccine-treated patients in the face of definite evidence of no impact on RFS. With further follow-up, however, the results of that randomized trial now show no significant adverse impact of the vaccine on either relapse or survival.

With more than 2000 patients treated on clinical trials of adjuvant HDI, several questions still remain. After reviewing these trials and combining the data into a meta-analysis, it is clear that HDI delays recurrences and improves disease-free survival. The OS benefit of HDI, if any, is small; in the meta-analysis all IFN-treated patients, regardless of dose and schedule, experienced a 10% relative decrease in the risk of death, which translated into a 2.8% increase in 5-year survival rate. Therefore when counseling patients regarding treatment with adjuvant HDI, several issues must be discussed at length. (1) How important is RFS for this individual patient? Patients and physicians often have differing opinions on this matter, with patients often placing more emphasis of RFS than physicians. (2) What is the toxicity of HDI? It is clear that with a relatively small overall benefit, one is less likely to give adjuvant IFN to patients with an increased risk of toxicities, such as those with already underlying severe psychiatric disorder, autoimmune disease, or poor cardiac, liver, or renal function. (3) What is the risk of relapse in any given patient?

Overall, most stage III melanoma patients should be counseled about adjuvant IFN and a lengthy discussion of its risks and benefits should be undertaken, with active patient participation. Observation alone or experimental trials are also valid choices to offer patients with stage III disease. High-risk stage II patients were included in all of the aforementioned trials, and though the benefit of adjuvant IFN in this subgroup of patients is even less clear than in stage III, some such patients will choose to pursue adjuvant treatment.

Pegylated Interferon as an Alternative to Standard Interferon

The many questions around the benefits of HDI, combined with the significant challenges patients face in undertaking this therapy (not the least of which are a month of daily visits to a hospital or clinic for intravenous infusions followed by thrice-weekly injections), has led to many clinical trials seeking alternatives. Pegylated IFN has a much longer half-life, allowing once a week injections to provide continuous drug exposure without the high peaks and long troughs (periods of time with undetectable blood IFN levels) associated with HDI. In Europe, where HDI has not been widely adopted, a large randomized trial (involving more than 1250 patients with stage III melanoma) compared pegylated IFNα-2b (Peg-IFN) administered for 5 years with observation. RFS, but not OS, was statistically significantly increased for patients randomized to Peg-IFN. Of particular interest, however, was the observation that patients with clinically occult nodal metastases diagnosed by sentinel node biopsy appeared to fare particularly well with Peg-IFN adjuvant therapy: both RFS and distant metastasis–free survival were significantly increased and there was a trend toward improved survival as well. Peg-IFN in this dose and schedule shares many of the substantial toxicities of HDI, but some patients will find it more convenient and, with appropriate and aggressive dose reduction to keep toxicities to a minimum level, many patients will find it possible to stay on therapy long-term with little or no impact on daily function. Recently, the Oncology Drug Advisory Committee voted to recommend that the FDA approve Peg-IFN as an alternative adjuvant approach for melanoma patients, but a final FDA decision on this point is still awaited.

Investigational Approaches with Vaccines and New Immunotherapies

Even if Peg-IFN is approved as an additional option for adjuvant therapy, it represents at best a small advance over existing approaches. Numerous other approaches have been tested, particularly vaccines designed to stimulate an immune response against any remaining melanoma cells in the body, but although some have shown promise in subsets of patients, none have reached the stage of FDA approval or widespread use. Indeed, the recent finding that some treated patients in several vaccine studies (including the ganglioside vaccine trial referred to previously) have fared worse than patients on observation or placebo has caused considerable consternation in the melanoma community. Even if (as is likely to be the case) long-term follow-up shows no actual adverse impact of melanoma vaccines, the failure of these trials to demonstrate an advantage for vaccination requires a rethinking of our approach to immunotherapy for melanoma in general.

Another immunomodulatory cytokine besides IFN that has been evaluated as an adjuvant therapy in melanoma is granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), alone or with vaccines. Nonrandomized trial data spurred interest in this agent, but the latest analysis of the large (800+ patients) randomized E4697 trial shows that GM-CSF alone or with a peptide vaccine failed to improve either RFS or OS. The current evidence clearly does not support the adjuvant use of GM-CSF outside the setting of a clinical trial. New agents with greater immunomodulatory effects, such as ipilimumab, are beginning to undergo testing in randomized adjuvant trials in patients with a high risk of relapse.

Neoadjuvant Therapy

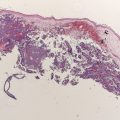

The role of neoadjuvant (preoperative) systemic therapy in melanoma is not well studied. In many other forms of cancer, systemic treatments with high response rates in the metastatic setting are brought into the neoadjuvant setting to reduce tumor size and potentially increase resectability of borderline or unresectable tumors. In melanoma, however, the standard treatments for metastatic disease have low response rates, with the 2 approved therapies, DTIC and high-dose interleukin-2, having response rates between 10% and 20%. Combination therapies, such as biochemotherapy (cytotoxic therapy plus immunotherapy), have yielded higher response rates in the metastatic setting, on the order of 48% to 60% in some series. The regimen of cisplatin, dacarbazine, and vinblastine combined with IFN and continuous infusion interleukin-2 has been studied in the neoadjuvant setting. Of the 50 patients with measurable disease in one recent study, biochemotherapy resulted in a partial or complete response in 13 patients for an overall response rate of 26%. A complete pathologic response was seen in 13 patients. However, the toxicities were significant and about 20% patients did not complete all 4 cycles of treatment secondary to toxicity. However, this does show that in a small number of select cases, biochemotherapy can have a clinical and pathologic response. HDI has also been studied in a small number of patients in the neoadjuvant setting. Twenty patients with stage IIIB and IIIC melanoma were given 4 weeks of intravenous IFN followed by lymph node dissection. Eleven patients had a clinical response and 3 patients had a complete pathologic response. This response rate for IFN is remarkable, but as yet it has not been validated in a confirmatory study.

Overall, neoadjuvant therapy is clearly not the standard of care in the management of stage III melanoma. However, a select group of patients may benefit from neoadjuvant systemic treatment with high response rates, such as biochemotherapy. These patients should ideally be young, healthy patients with tumors that are not or are borderline resectable, selected after careful imaging studies and with the involvement of surgical, medical, and radiation oncologists.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree