Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in the United States and disproportionately affects the elderly. In 2009, breast, colorectal, and lung cancer together accounted for more than one third of the 1.5 million expected diagnoses of cancer, and for about 250,000 deaths. The median age of cancer diagnosis in breast, colorectal, and lung cancers was 61 years, 71 years, and 71 years, respectively.

Adjuvant therapy is defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as “additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment to lower the risk that the cancer will come back.” Adjuvant therapy is generally aimed at eliminating residual disease left behind at surgery. Decisions regarding the utility of adjuvant therapy weigh the likelihood of recurrence with the patient’s life expectancy and susceptibility to short- and long-term toxicities. Over the past decade, increased screening with colonoscopy, mammography, and computed tomography (CT) of the chest has resulted in cancer detection at earlier stages. Multiple different treatment modalities, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and biologic or targeted therapy may have a role in the treatment of early-stage cancer. Because elderly patients are often underrepresented in clinical trials, the benefits and risks in elderly populations are not well understood. However, even in settings of proven benefit, elderly patients are frequently not as likely to be offered or to receive curative therapy.

The goals of this chapter are to introduce the major principles and fundamental practices of adjuvant therapy for breast, colon, and lung cancer in elderly patients. By the end, the reader should understand the factors that contribute to the decision to use or withhold adjuvant therapy. These factors include tumor and patient characteristics, as well as the benefits and toxicities associated with each therapy. Case presentations will highlight the challenges to providing appropriate cancer care for an individual patient. The specific cancer sections will explore prognostic factors and factors predictive of response to therapy, both of which play important roles in decisions regarding adjuvant therapy. The cancer-specific section will also offer an overview of the therapies used to treat breast, colon, and lung cancer, with a focus on how the use of those therapies may be different in older patients.

Predictors of Benefit from Adjuvant Therapy

Decision making about the use of adjuvant therapy is influenced by tumor and patient characteristics.

Tumor Characteristics

A prognostic factor is defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as an element that can be used to define the chance of recovery from a disease or the risk or relapse. A predictive factor is used to estimate the likelihood that a patient will respond to a particular therapy. Many tumor characteristics have important prognostic and predictive value. Prognostic indicators in breast cancer include tumor stage and grade, lymphovascular invasion, and hormone receptor status. Hormone receptor status and increased HER-2/neu expression also predict response to hormonal therapy and trastuzumab, respectively. Prognostic indicators in colon cancer include tumor stage, grade, lymphovascular invasion, and preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Stage and grade are unique in their almost universal prognostic value for varied tumor types. Additional prognostic and predictive factors will be reviewed in the cancer-specific sections.

The risk of relapse after primary surgical therapy is the main contributor to any decision regarding the benefit of adjuvant therapy; often a patient whose cancer is more likely to relapse is also more likely to benefit from adjuvant therapy. Stage of disease is one of the strongest predictors of relapse risk. Staging is defined by the TNM system, established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), where T refers to the size of the primary tumor, N refers to the degree of lymph node involvement, and M refers to the presence or absence of distant metastases. The relationship between advancing age and stage varies by cancer. In multiple analyses, older breast cancer patients presented with more advanced-stage disease while older colon cancer patients presented at stages similar to younger patients, and older lung cancer patients presented with earlier-stage disease. It is also noteworthy that changes in screening and medical care will influence the relationship between age and stage at diagnosis. Evidence suggests that both increased mammography and decreased use of hormone replacement therapy have contributed to the decrease in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in women in their 60s.

The grade of the tumor is also an important determinant of relapse risk. Although the specifics of tumor grade differ by tumor type, higher grade tumors are typically recognized by higher rates of cellular proliferation, increased invasion into surrounding tissue, and less similarity to their tissues of origin. As cancer cells acquire additional genetic changes that increase their potential to invade and metastasize, they frequently appear histologically to be less like their tissues of origin. The relationship between advancing age and tumor grade is variable by tumor type. Other tumor characteristics, including hormonal receptor status, lymphovascular space invasion, presence and absence of genetic alterations, and tumor genetic profiles influence relapse risk.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics, including life expectancy and the risk of treatment-related adverse outcomes, factor into any risk-benefit analysis about adjuvant therapy. Advanced age does not, by itself, predict toxicity from or poor response to therapy. Advanced age is, however, associated with multiple other physiologic changes, including decreased performance status and increased numbers of comorbid conditions that may change the effects of therapy.

Pharmacokinetics

With advancing age, the body fat percentage increases, which decreases total body water and decreases the volume of distribution. There is also an age-related decrease in glomerular filtration rate that prolongs the effects of medications excreted by the kidney, and which limits the use of medications with renal toxicity. In addition, creatinine becomes a poor marker of glomerular filtration rate in elderly patients because of their decrease in muscle mass, which may not be recognized by the treating physician.

Comorbidities

Coexisting renal or hepatic disease will change the half-life of administered medications, with resultant changes in the toxicity profile. Other comorbid conditions may influence the effects of therapy in ways that are less obvious. The Charlson comorbidity index was designed to predict 1-year mortality on the basis of a weighted composite score for the following categories: cardiovascular, endocrine, pulmonary, neurologic, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, and neoplastic disease. One study of more than 1200 patients with non-small cell lung cancer noted that although a higher Charlson comorbidity score was associated with increasing age, only higher comorbidity score, and not age, was independently associated with decreased survival.

Performance Status

Performance status is used to quantify the patient’s functional capabilities. The two most widely used scales for performance status in oncology are the Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scales. Several studies have shown that poor performance status is associated with increased therapy-related toxicity and poor survival. While predictive of outcome, there is evidence that these performance status scales may underestimate the degree of functional impairment in older patients, when compared with the activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scales.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

The comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) generally includes functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognitive status, psychological conditions, nutritional status, and medication review. Functional status in a CGA may be assessed by the ADL and IADL, both of which focus on the patient’s ability to complete specific daily tasks in and out of the home. The CGA predicts overall survival and toxicity of cancer treatment. It adds additional valuable information to assessments of performance status alone.

Functional Reserve

Older patients may experience more severe toxicities than younger patients. For example, several studies have suggested significantly increased rates of neutropenia in patients older than 70 years who are receiving chemotherapy, after controlling for other risk factors. Chemotherapeutics known to damage the heart have been shown to be more toxic in patients older than 65. In many circumstances, the distinction between age as an independent predictor of toxicity or age as a marker for other changes that predict toxicity is unknown. Other studies have found similar rates of severe toxicity in younger and older patients treated with chemotherapy, albeit in highly selected patient populations.

Therapy Characteristics

Each cancer-related therapy has a distinct toxicity profile, that may or may not be influenced by the patient’s age, and which is weighed against the likelihood of benefit for the patient.

Tumor Characteristics

A prognostic factor is defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as an element that can be used to define the chance of recovery from a disease or the risk or relapse. A predictive factor is used to estimate the likelihood that a patient will respond to a particular therapy. Many tumor characteristics have important prognostic and predictive value. Prognostic indicators in breast cancer include tumor stage and grade, lymphovascular invasion, and hormone receptor status. Hormone receptor status and increased HER-2/neu expression also predict response to hormonal therapy and trastuzumab, respectively. Prognostic indicators in colon cancer include tumor stage, grade, lymphovascular invasion, and preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Stage and grade are unique in their almost universal prognostic value for varied tumor types. Additional prognostic and predictive factors will be reviewed in the cancer-specific sections.

The risk of relapse after primary surgical therapy is the main contributor to any decision regarding the benefit of adjuvant therapy; often a patient whose cancer is more likely to relapse is also more likely to benefit from adjuvant therapy. Stage of disease is one of the strongest predictors of relapse risk. Staging is defined by the TNM system, established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), where T refers to the size of the primary tumor, N refers to the degree of lymph node involvement, and M refers to the presence or absence of distant metastases. The relationship between advancing age and stage varies by cancer. In multiple analyses, older breast cancer patients presented with more advanced-stage disease while older colon cancer patients presented at stages similar to younger patients, and older lung cancer patients presented with earlier-stage disease. It is also noteworthy that changes in screening and medical care will influence the relationship between age and stage at diagnosis. Evidence suggests that both increased mammography and decreased use of hormone replacement therapy have contributed to the decrease in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in women in their 60s.

The grade of the tumor is also an important determinant of relapse risk. Although the specifics of tumor grade differ by tumor type, higher grade tumors are typically recognized by higher rates of cellular proliferation, increased invasion into surrounding tissue, and less similarity to their tissues of origin. As cancer cells acquire additional genetic changes that increase their potential to invade and metastasize, they frequently appear histologically to be less like their tissues of origin. The relationship between advancing age and tumor grade is variable by tumor type. Other tumor characteristics, including hormonal receptor status, lymphovascular space invasion, presence and absence of genetic alterations, and tumor genetic profiles influence relapse risk.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics, including life expectancy and the risk of treatment-related adverse outcomes, factor into any risk-benefit analysis about adjuvant therapy. Advanced age does not, by itself, predict toxicity from or poor response to therapy. Advanced age is, however, associated with multiple other physiologic changes, including decreased performance status and increased numbers of comorbid conditions that may change the effects of therapy.

Pharmacokinetics

With advancing age, the body fat percentage increases, which decreases total body water and decreases the volume of distribution. There is also an age-related decrease in glomerular filtration rate that prolongs the effects of medications excreted by the kidney, and which limits the use of medications with renal toxicity. In addition, creatinine becomes a poor marker of glomerular filtration rate in elderly patients because of their decrease in muscle mass, which may not be recognized by the treating physician.

Comorbidities

Coexisting renal or hepatic disease will change the half-life of administered medications, with resultant changes in the toxicity profile. Other comorbid conditions may influence the effects of therapy in ways that are less obvious. The Charlson comorbidity index was designed to predict 1-year mortality on the basis of a weighted composite score for the following categories: cardiovascular, endocrine, pulmonary, neurologic, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, and neoplastic disease. One study of more than 1200 patients with non-small cell lung cancer noted that although a higher Charlson comorbidity score was associated with increasing age, only higher comorbidity score, and not age, was independently associated with decreased survival.

Performance Status

Performance status is used to quantify the patient’s functional capabilities. The two most widely used scales for performance status in oncology are the Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scales. Several studies have shown that poor performance status is associated with increased therapy-related toxicity and poor survival. While predictive of outcome, there is evidence that these performance status scales may underestimate the degree of functional impairment in older patients, when compared with the activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scales.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

The comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) generally includes functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognitive status, psychological conditions, nutritional status, and medication review. Functional status in a CGA may be assessed by the ADL and IADL, both of which focus on the patient’s ability to complete specific daily tasks in and out of the home. The CGA predicts overall survival and toxicity of cancer treatment. It adds additional valuable information to assessments of performance status alone.

Functional Reserve

Older patients may experience more severe toxicities than younger patients. For example, several studies have suggested significantly increased rates of neutropenia in patients older than 70 years who are receiving chemotherapy, after controlling for other risk factors. Chemotherapeutics known to damage the heart have been shown to be more toxic in patients older than 65. In many circumstances, the distinction between age as an independent predictor of toxicity or age as a marker for other changes that predict toxicity is unknown. Other studies have found similar rates of severe toxicity in younger and older patients treated with chemotherapy, albeit in highly selected patient populations.

Pharmacokinetics

With advancing age, the body fat percentage increases, which decreases total body water and decreases the volume of distribution. There is also an age-related decrease in glomerular filtration rate that prolongs the effects of medications excreted by the kidney, and which limits the use of medications with renal toxicity. In addition, creatinine becomes a poor marker of glomerular filtration rate in elderly patients because of their decrease in muscle mass, which may not be recognized by the treating physician.

Comorbidities

Coexisting renal or hepatic disease will change the half-life of administered medications, with resultant changes in the toxicity profile. Other comorbid conditions may influence the effects of therapy in ways that are less obvious. The Charlson comorbidity index was designed to predict 1-year mortality on the basis of a weighted composite score for the following categories: cardiovascular, endocrine, pulmonary, neurologic, renal, hepatic, gastrointestinal, and neoplastic disease. One study of more than 1200 patients with non-small cell lung cancer noted that although a higher Charlson comorbidity score was associated with increasing age, only higher comorbidity score, and not age, was independently associated with decreased survival.

Performance Status

Performance status is used to quantify the patient’s functional capabilities. The two most widely used scales for performance status in oncology are the Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scales. Several studies have shown that poor performance status is associated with increased therapy-related toxicity and poor survival. While predictive of outcome, there is evidence that these performance status scales may underestimate the degree of functional impairment in older patients, when compared with the activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scales.

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

The comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) generally includes functional status, comorbid medical conditions, cognitive status, psychological conditions, nutritional status, and medication review. Functional status in a CGA may be assessed by the ADL and IADL, both of which focus on the patient’s ability to complete specific daily tasks in and out of the home. The CGA predicts overall survival and toxicity of cancer treatment. It adds additional valuable information to assessments of performance status alone.

Functional Reserve

Older patients may experience more severe toxicities than younger patients. For example, several studies have suggested significantly increased rates of neutropenia in patients older than 70 years who are receiving chemotherapy, after controlling for other risk factors. Chemotherapeutics known to damage the heart have been shown to be more toxic in patients older than 65. In many circumstances, the distinction between age as an independent predictor of toxicity or age as a marker for other changes that predict toxicity is unknown. Other studies have found similar rates of severe toxicity in younger and older patients treated with chemotherapy, albeit in highly selected patient populations.

Disease-Specific Issues: Breast Cancer

A 74-year-old woman presents with a 4 cm mass in the left breast, discovered on her first mammogram in 5 years. Needle biopsy confirmed adenocarcinoma that expressed estrogen and progesterone receptors, but which did not overexpress the HER-2/neu protein receptor.

Pretherapy Evaluation

Comprehensive geriatric assessment reveals that the patient is completely independent by the IADL scale. Her only comorbidity is diabetes, which is controlled with oral medications; she shows no evidence of end-organ damage. She continues to work as an accountant, takes care of two grandchildren every Wednesday, and walks four mornings a week with her closest friends. The patient’s cognitive function, nutritional status, and psychological state are excellent. Her medications include metformin and a daily baby aspirin.

Clinical Staging

On physical exam, the patient has a palpable 4 cm, firm, mobile nodule in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast, and a 2 cm palpable node in the left axilla.

Mastectomy versus Breast-Conserving Therapy

Total, or simple, mastectomy includes removal of the whole breast and the fascia overlying the pectoralis major. Breast-conserving surgery removes the tumor mass with specimen margins that are free of tumor. Prospective randomized trials have established the equivalence of mastectomy and the combination of breast-conserving surgery and radiation, while breast-conserving surgery without radiation results in a higher local recurrence rate and worsened survival. The decision regarding appropriate breast surgery is challenging and personal. The absolute contraindications to breast-conserving surgery include multicentric disease, diffuse calcifications on mammogram, prior radiation to the chest wall, and inability to obtain clean margins. Relative contraindications to breast-conserving therapy include connective tissue disease and large tumor size relative to breast size. In addition, patients who are unable to receive radiation because of logistical issues may not be appropriate candidates for breast conservation surgery.

Older women are less likely to have breast-conserving surgery, and those who have it are less likely to have radiation therapy when compared to younger women. A patient’s decision as to whether to undergo a mastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy is strongly influenced by her physician’s recommendation.

Axillary nodal evaluation by sentinel node biopsy or nodal dissection is the standard of care for all women with invasive breast cancer. Older women are significantly less likely to have axillary lymph node dissection. For some, this may be appropriate, as there is evidence that women older than 70 years with estrogen receptor-expressing tumors and tumors less than 2 cm with no clinical axillary involvement may be safely treated with resection followed by tamoxifen, without axillary nodal exploration. Guidelines suggest that axillary node evaluation should not be omitted in a patient who is being considered for any adjuvant therapy in addition to hormonal therapy, and specifically should be pursued in patients with higher-risk cancers.

The patient proceeded to a lumpectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Additional laboratory data and chest x-ray were unremarkable. The final staging is pathologic T2 (tumor >2 cm, but <5 cm), N1 (nodal involvement in 1 to 3 ipsilateral axillary nodes), M0 (no distant metastases), stage IIB. The patient had a normal echocardiogram with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%.

Prognostic and Predictive Factors Stage

As noted earlier, cancer stage is a universal predictor of the patient’s overall prognosis. The cancer Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database tracks cancers in the US in a representative 26% of the population. In the year 2000, from the SEER database, 60% of breast cancer cases were diagnosed as localized disease with the cancer confined to the primary site; 33% were diagnosed as regional disease with spread beyond the primary site or into the local lymph nodes; and 5% were metastatic at diagnosis. The 5-year relative survival rate for localized disease was 98.3%; for regional disease, 83.5%; and for metastatic disease, 23.3%. Older patients with breast cancer are more likely than younger patients to present with metastatic disease.

Histology and Grade

Grade has been described earlier and represents a composite evaluation of the tumor’s aggressiveness by histologic criteria. Grade is a well-established predictor of outcome. Older patients tend to present with breast cancer with lower proliferative rates and lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion, both markers of less aggressive behavior. Breast cancer may present with variable histologic patterns, and these histologic subtypes may have different clinical behavior. Approximately 75% of women with invasive breast carcinoma, a cancer of epithelial cell origin, have infiltrating ductal type carcinoma. Patients who have a component of invasive lobular carcinoma frequently present at a more advanced stage than those with purely infiltrating ductal carcinoma, and their tumors are more likely to be hormone-sensitive.

Hormone Receptor Status

The expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors on the surface of breast cancer cells is both prognostic and predictive of response to hormonal therapy. Collectively, patients who are either estrogen- and/or progesterone-receptor positive live longer than patients whose tumors are hormone receptor-negative. This association holds true after accounting for age, stage, histology, and other demographic variables. The association is also maintained in both older and younger women. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that is an estrogen receptor antagonist in breast tissue and an agonist in other tissues, including bone and uterus. Estrogen receptor (ER) status strongly predicts response to tamoxifen therapy, with a 31% reduction in the annual breast cancer death rate in ER-positive patients and no effect on patients with ER-negative disease. For postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitor therapy, either alone or given sequentially with tamoxifen, has been shown in multiple clinical trials to be superior to tamoxifen therapy alone.

HER-2 Status

HER-2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Approximately 18% to 20% of breast cancer patients overexpress the HER-2 protein. Older women are less likely to express HER-2 than younger women. HER-2 expression predicted poor cause-specific survival in both older and younger women prior to the use of trastuzumab, an anti-HER-2 antibody. The benefit of trastuzumab is confined to those patients with immunohistochemically confirmed overexpression of HER-2 or fluorescence in situ hybridization-confirmed elevated gene copy number of HER-2/neu.

Overall Prognosis

The overall prognosis of elderly women with breast cancer is the net effect of the biology of the tumor and the efficacy and tolerability of therapy. The overall prognosis of older women has been reported in some studies to be comparable to the prognosis for younger women and in other studies to be worse than the prognosis for younger women. Differences in receipt of adjuvant therapy likely contribute to these disparate results. In a study of 407 women aged 80 years or older who were treated during the 1990s, 12% received no therapy; 32%, tamoxifen only; 7%, breast-conserving therapy only; 33%, mastectomy; and 14%, breast-conserving therapy with adjuvant radiation therapy. The 5-year breast cancer specific survival for these groups were 46%, 51%, 82%, and 90%, respectively. Age was strongly associated with less-aggressive treatment after controlling for tumor type, general health status, and comorbidities.

Adjuvant Therapies: Radiotherapy

Adjuvant radiotherapy may be used in two settings: after breast-conserving therapy and after mastectomy. A review of almost 50,000 women age 65 or older treated for breast cancer in the 1990s found that approximately 76% of the patients who had lumpectomies also had radiation therapy. Receipt of postlumpectomy radiation therapy was associated with later year of diagnosis, younger age, fewer comorbidities, nonrural residence, chemotherapy, white race, and no prior history of heart disease. Older age has also been associated with longer delay between lumpectomy and radiation therapy. In a randomized trial of 636 women older than 70 years with small, node-negative, ER-positive breast cancer who were assigned to either BCT with tamoxifen and radiotherapy or BCT with tamoxifen only, found that risk of local relapse was increased at 5 years, from 1% to 4% without radiation; however, survival was not significantly different between the groups.

Adjuvant Therapies: Systemic

Chemotherapy

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends adjuvant chemotherapy for all patients less than 70 years old with nodal involvement or with tumors larger than 1 cm. The guidelines recommend consideration of chemotherapy for patients with tumors between 0.6 and 1 cm after evaluation of hormone receptor status, HER-2 status, and other unfavorable features including angiolymphatic invasion, high nuclear grade, or high histologic grade. Common chemotherapeutic drugs used include doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, paclitaxel, and docetaxel. A meta-analysis of 194 randomized trials of adjuvant chemotherapy begun by 1990 found that anthracycline-containing compounds reduced the annual breast cancer death rate by 38% in patients younger than 50 years, and by 20% in patients aged 50 to 69. Few patients older than 70 were included in these trials. Another meta-analysis established the survival benefit of adding a taxane to anthracycline chemotherapy, regardless of patient age. In a dose-dependent fashion, anthracycline chemotherapy is associated with development of cardiomyopathy in elderly patients with hypertension. In an effort to avoid the anthracycline toxicity, docetaxel and cyclophosphamide were compared to doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of early breast cancer. Sixteen percent of the trial participants were age 65 or older and, after 7 years of follow up, both disease-free survival and overall survival were better in the docetaxel/cyclophosphamide arm.

In a single institution study of more than 1500 women aged 55 or older treated for breast cancer between 1997 and 2002, older age was a significant predictor of not receiving chemotherapy when indicated by guideline recommendations. This association remained after controlling for confounding factors such as stage, tumor characteristics, comorbidity score, and other demographic variables. To assess the toxicity of chemotherapy for older patients in the community, one analysis of SEER-Medicare data from 1991 to 1996 found that the hospitalization rate for chemotherapy complications was 9%, which increased with increasing stage of cancer and increasing comorbidities, but did not differ by age category. An evaluation of data from four randomized trials of adjuvant therapy that compared a higher dose or more intense chemotherapy regimen with a lower dose or less intense regimen suggested that more chemotherapy was associated with longer disease-free and overall survival. There was no association between age and disease-free survival. Older patients had more non–breast cancer-related deaths.

Molecularly Targeted Therapy

Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against the HER-2/neu receptor, is recommended for use in patients with HER-2/neu overexpression or gene amplification and tumors larger than 2 centimeters or lymph node involvement who are receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The benefit of trastuzumab was established in a combined analysis of two randomized trials that demonstrated a 33% decreased risk of death among patients who received trastuzumab. Trastuzumab is typically started either with or after chemotherapy and continued weekly to complete 1 year of therapy. Major toxicities of trastuzumab include cardiomyopathy, allergic infusion reactions, and variable pulmonary toxicities. Data on the use of trastuzumab in elderly patients are limited, but suggest that efficacy and toxicity are similar in all age groups.

Hormonal Therapy

The goal of hormonal therapy for breast cancer is to reduce estrogen stimulation of the tumor. Three major modalities are used to reduce estrogen stimulation: ovarian ablation, by oophorectomy, with radiation, or by chemical means with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH); estrogen receptor blockade by a partial agonist (tamoxifen); and blockade of peripheral estrogen production by an aromatase inhibitor, in women without functioning ovaries. A meta-analysis of the effects of hormonal therapy in randomized trials of more than 60,000 patients demonstrated that for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, tamoxifen therapy for 5 years reduced the annual breast cancer death rate by 31% over 15 years, irrespective of patient age. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) decrease conversion of androgen precursors into estrogens, and have been shown to be superior to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women in a number of large randomized trials. AIs are less likely to cause venous thromboembolic events and endometrial cancer, but are more likely to result in arthralgias and accelerated bone loss. Aromatase inhibitors are now recommended by the NCCN as first-line hormonal therapy for postmenopausal women. Subgroup analyses of the older patients in the aromatase inhibitor trials confirm that AIs have similar efficacy and toxicity in older and younger postmenopausal patients. A review of more than 1500 breast cancer patients treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1997 and 2002 noted that, after accounting for comorbidities and stage, among only patients with good performance status, in situations where guidelines recommended hormonal therapy, women aged 75 and older were 90% less likely to be treated with hormonal therapy than women aged 55 to 64. Challenges to the effective use of adjuvant hormonal therapy include poor compliance and high cost.

Decision Aids for Medical Therapy

Adjuvant! Online

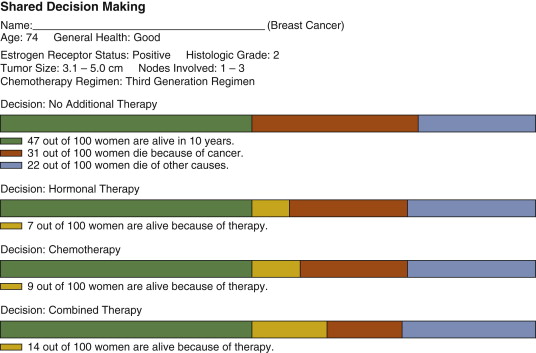

The large amount of clinical and pathologic prognostic and predictive information is difficult to integrate into an overall assessment of prognosis for an individual patient. Adjuvant! Online is a program that synthesizes patient age, comorbidity, ER status, tumor grade, tumor size, and number of positive nodes to determine an overall risk of recurrence and death at 10 years. The program has been validated in multiple cohorts. The program also calculates the benefit of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy on the basis of data from large randomized trials. The results can be displayed in graphic form, printed, and given to the patient to help clarify the benefits of adjuvant therapy.

Oncotype

Traditionally, women with small, hormone-sensitive cancers have been most difficult to counsel regarding the risks and benefits of chemotherapy. Recently, a diagnostic tool has been developed, Oncotype DX, that quantifies the expression of 21 genes in a woman’s tumor sample, and generates a numerical risk of distant recurrence assuming the patient were to take hormonal therapy alone. The results characterize whether the patient has low, intermediate, or high risk of relapse, which corresponds to relapse rates of approximately 7%, 14%, and 31%, respectively. The results are independent of age. Retrospective studies show that tumors with high recurrence scores have a large benefit from chemotherapy and those with low recurrence scores have no benefit from chemotherapy. Ongoing prospective studies are validating the predictive benefit of chemotherapy in patients with intermediate risk of metastatic recurrence

MammaPrint

The MammaPrint assay uses gene expression array technology on 70 genes to classify tumors as either good or poor prognosis. It was developed and validated on a cohort of women that included both hormone receptor negative and positive disease, as well as patients

In preparation for discussion of the risks and benefits of adjuvant therapies, the patient’s profile was entered into the Adjuvant! Program ( Fig 8-1 ). According to the Adjuvant! algorithm, approximately 42 patients out of one hundred patients with this profile who receive no therapy will be alive in 10 years. Twenty-nine patients are expected to die from causes other than cancer, and 29 patients are expected to die from cancer. Adding hormonal therapy would be expected to decrease the cancer related mortality by approximately 7%, and adding chemotherapy to that would be expected to decrease the cancer-related mortality by an additional 14%. The patient decided that she would pursue treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy.

Summary

Decisions regarding adjuvant therapy for older patients with breast cancer are complex and involve consideration of all possible adjuvant options (radiation, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and hormonal therapy). They must factor in the patient’s priorities, medical conditions, functionality, and the likelihood of tumor recurrence. Therapy should not be withheld on the basis of chronological age alone.

Predictive and Prognostic Factors

Pathologic Stage

Colorectal cancers may spread by direct extension, or by hematogenous, or lymphatic routes. Hematogenous dissemination from most of the colon typically follows the venous drainage to involve the liver prior to the lungs. A notable exception to this is distal rectal cancer which, because of venous drainage directly into the inferior vena cava, may metastasize to the lungs without involvement of the liver. T stage in colon cancer is related to depth of invasion, without reference to the size of the mass. An evaluation of population outcomes in patients with colon cancer from the SEER database found 5-year stage-specific survival of 93.2% for stage I, 82.5% for stage II, 59.5% for stage III, and 8.1% for stage IV. Number of nodes involved is an important

Case

A 76-year-old man with hyperlipidemia presents with black stool. On colonoscopy he is noted to have a 3 cm mass in the descending colon. The biopsy confirms adenocarcinoma.

Clinical Staging and Presurgical Evaluation

The patient’s only comorbidities are hypercholesterolemia and hypertension. He takes atenolol and lovastatin. He lives with his wife of 18 years, retired 7 years ago from the U.S. Postal Service, and is an avid golfer. He routinely does the grocery shopping for the family. His weight is stable at 192 pounds and he is 72 inches tall. The comprehensive geriatric assessment suggests that his functional status, cognitive ability, nutritional status, and psychological profile are all adequate. The patient’s laboratory analyses reveal a mild microcytic hypochromic anemia, and are otherwise normal. His CEA level is not elevated. CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis show no pathologic findings other than the mass in the descending colon.

Primary Therapy

The patient decides to proceed with hemicolectomy and lymph node dissection. Pathologic evaluation reveals an intermediate grade T3 (tumor invades through the muscularis into the subserosa), N2 (involvement of 4 or more lymph nodes) tumor, and the final stage is IIIC.

Grade and Tumor Features

Tumor grade also predicts outcome in patients with colorectal cancers. Older patients present with high-grade tumors as frequently as do younger patients. Additional features of the biopsy specimen, including vascular invasion, lymphatic invasion, and positive surgical margins are also prognostic indicators.

Histology

More than 95% of all colon cancers are adenocarcinomas. One histologic subtype, signet ring cell carcinoma, which represents only approximately 1% of all adenocarcinomas of the colon, is associated with poorer prognosis.

Biochemical and Molecular Markers

Carcinoembryonic antigen is a glycoprotein that is overexpressed in adenocarcinoma relative to normal colon epithelial cells. Its function has not been completely elucidated, but localization on the cell surface and homology with other adhesion molecules suggests a role in cell-cell interactions. DNA microsatellite instability is a marker of poor DNA mismatch repair. Microsatellite instability in tumor tissue is used to screen for the genetic defects that cause hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), and is also found in 10% to 15% of sporadic colon cancers. For reasons that are not entirely clear, low microsatellite instability (i.e., effective DNA mismatch repair) is associated with poor prognosis in sporadic colon cancer. The relationship between microsatellite instability and age remains poorly defined.

The ras intracellular signaling molecule plays a key role in growth signaling transfer from cell surface epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) and nuclear DNA targets. Activating mutations of the K-ras can decrease cancer dependence on external stimuli via the EGFR. Mutant K-ras has also been shown to be an important determinant of poor response to therapy with anti-EGFR antibodies in advanced colorectal cancer.

Adjuvant Therapy

Chemotherapy

A benefit for chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil [5-FU] and leucovorin) over observation was first established in a pooled analysis of three randomized trials that demonstrated a 22% decrease in mortality associated with the receipt of chemotherapy in patients with stage III colon cancer. Subsequently, the MOSAIC trial showed an absolute 5% disease-free survival advantage at 3 years for patients with stage III colon cancer who received adjuvant infusional 5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) relative to those who received 5-FU and leucovorin alone. Patients in the FOLFOX arm experienced more neuropathy, hematologic, and gastrointestinal toxicity. Elderly patients are underrepresented in clinical trials, but both observational and subset analyses confirm the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients. Sargent and colleagues pooled elderly patient data from seven phase III trials of adjuvant 5-FU based therapy and found an overall survival benefit of 24% compared to no therapy in all age groups, including the 506 patients older than age 70. A small prospective study reported increased, but tolerable, levels of neuropathy and neutropenia in patients aged 76 to 80 years old. Similar benefit has been reported in multiple population-based studies. An analysis of patients aged 65 or older in the SEER-Medicare database with stage III colon cancer reported that only 52% received adjuvant 5-FU; however, among those treated with 5-FU there was a 34% reduction in mortality. The decision regarding the use and type of adjuvant chemotherapy is increasingly complicated with newer and often more toxic chemotherapy regimens.

Molecularly Targeted Therapy

Although bevacizumab is used in metastatic colon cancer, no significant benefit for bevacizumab therapy was seen in a randomized trial of patients with early-stage colon cancer.

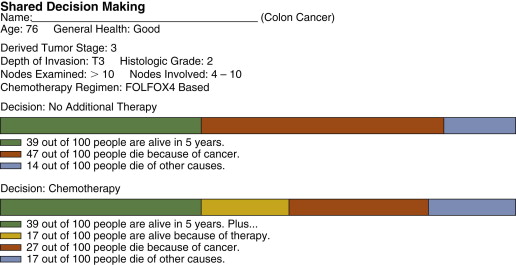

Decision Aids

As in breast cancer, the wealth of prognostic information from clinical, pathologic, and molecular features of each case is difficult to integrate into an adjuvant therapy benefit. The Adjuvant! program includes a prognosis and benefit estimator for colon cancer. The colon cancer recurrence calculation incorporates patient age, gender, comorbidity, depth of invasion, grade, number of positive nodes, and number of examined nodes.

Recurrence Score

Early studies suggest that a recently validated 18 gene recurrence score may predict colon cancer recurrence and overall survival independent of mismatch repair, tumor grade, stage, lymphovascular invasion, and nodes examined. The clinical implications of the recurrence score with regard to treatment benefits are unknown.

The Adjuvant! program estimates that for this patient who is in good health with a high T and N stage tumor that his likelihood of dying from cancer within the next 5 years is approximately 47% ( Fig 8-2 ). The program estimates that using adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin will reduce the likelihood of dying from the cancer by 17%. After discussion with his treating physicians and consideration of his independent performance of activities of daily living and ECOG performance status score of 0, as well as his strong desire to use all available therapy to maximize his chance of long-term survival, the patient decides that he would like to undergo treatment with adjuvant 5-FU and oxaliplatin.

Summary

Adjuvant therapy for colon cancer in the elderly should include consideration of stage, grade, CEA level, and anatomy; a geriatric assessment; and patient preference. Chemotherapy is the standard of care for patients with stage III colon cancer, but current regimens cause substantial toxicity for older and younger patients.

A 74-year-old woman presents with a 4 cm mass in the left breast, discovered on her first mammogram in 5 years. Needle biopsy confirmed adenocarcinoma that expressed estrogen and progesterone receptors, but which did not overexpress the HER-2/neu protein receptor.

Pretherapy Evaluation

Comprehensive geriatric assessment reveals that the patient is completely independent by the IADL scale. Her only comorbidity is diabetes, which is controlled with oral medications; she shows no evidence of end-organ damage. She continues to work as an accountant, takes care of two grandchildren every Wednesday, and walks four mornings a week with her closest friends. The patient’s cognitive function, nutritional status, and psychological state are excellent. Her medications include metformin and a daily baby aspirin.

Pretherapy Evaluation

Comprehensive geriatric assessment reveals that the patient is completely independent by the IADL scale. Her only comorbidity is diabetes, which is controlled with oral medications; she shows no evidence of end-organ damage. She continues to work as an accountant, takes care of two grandchildren every Wednesday, and walks four mornings a week with her closest friends. The patient’s cognitive function, nutritional status, and psychological state are excellent. Her medications include metformin and a daily baby aspirin.

Mastectomy versus Breast-Conserving Therapy

Total, or simple, mastectomy includes removal of the whole breast and the fascia overlying the pectoralis major. Breast-conserving surgery removes the tumor mass with specimen margins that are free of tumor. Prospective randomized trials have established the equivalence of mastectomy and the combination of breast-conserving surgery and radiation, while breast-conserving surgery without radiation results in a higher local recurrence rate and worsened survival. The decision regarding appropriate breast surgery is challenging and personal. The absolute contraindications to breast-conserving surgery include multicentric disease, diffuse calcifications on mammogram, prior radiation to the chest wall, and inability to obtain clean margins. Relative contraindications to breast-conserving therapy include connective tissue disease and large tumor size relative to breast size. In addition, patients who are unable to receive radiation because of logistical issues may not be appropriate candidates for breast conservation surgery.

Older women are less likely to have breast-conserving surgery, and those who have it are less likely to have radiation therapy when compared to younger women. A patient’s decision as to whether to undergo a mastectomy versus breast-conserving therapy is strongly influenced by her physician’s recommendation.

Axillary nodal evaluation by sentinel node biopsy or nodal dissection is the standard of care for all women with invasive breast cancer. Older women are significantly less likely to have axillary lymph node dissection. For some, this may be appropriate, as there is evidence that women older than 70 years with estrogen receptor-expressing tumors and tumors less than 2 cm with no clinical axillary involvement may be safely treated with resection followed by tamoxifen, without axillary nodal exploration. Guidelines suggest that axillary node evaluation should not be omitted in a patient who is being considered for any adjuvant therapy in addition to hormonal therapy, and specifically should be pursued in patients with higher-risk cancers.

The patient proceeded to a lumpectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Additional laboratory data and chest x-ray were unremarkable. The final staging is pathologic T2 (tumor >2 cm, but <5 cm), N1 (nodal involvement in 1 to 3 ipsilateral axillary nodes), M0 (no distant metastases), stage IIB. The patient had a normal echocardiogram with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%.

The patient proceeded to a lumpectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Additional laboratory data and chest x-ray were unremarkable. The final staging is pathologic T2 (tumor >2 cm, but <5 cm), N1 (nodal involvement in 1 to 3 ipsilateral axillary nodes), M0 (no distant metastases), stage IIB. The patient had a normal echocardiogram with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%.

Prognostic and Predictive Factors Stage

As noted earlier, cancer stage is a universal predictor of the patient’s overall prognosis. The cancer Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database tracks cancers in the US in a representative 26% of the population. In the year 2000, from the SEER database, 60% of breast cancer cases were diagnosed as localized disease with the cancer confined to the primary site; 33% were diagnosed as regional disease with spread beyond the primary site or into the local lymph nodes; and 5% were metastatic at diagnosis. The 5-year relative survival rate for localized disease was 98.3%; for regional disease, 83.5%; and for metastatic disease, 23.3%. Older patients with breast cancer are more likely than younger patients to present with metastatic disease.

Histology and Grade

Grade has been described earlier and represents a composite evaluation of the tumor’s aggressiveness by histologic criteria. Grade is a well-established predictor of outcome. Older patients tend to present with breast cancer with lower proliferative rates and lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion, both markers of less aggressive behavior. Breast cancer may present with variable histologic patterns, and these histologic subtypes may have different clinical behavior. Approximately 75% of women with invasive breast carcinoma, a cancer of epithelial cell origin, have infiltrating ductal type carcinoma. Patients who have a component of invasive lobular carcinoma frequently present at a more advanced stage than those with purely infiltrating ductal carcinoma, and their tumors are more likely to be hormone-sensitive.

Hormone Receptor Status

The expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors on the surface of breast cancer cells is both prognostic and predictive of response to hormonal therapy. Collectively, patients who are either estrogen- and/or progesterone-receptor positive live longer than patients whose tumors are hormone receptor-negative. This association holds true after accounting for age, stage, histology, and other demographic variables. The association is also maintained in both older and younger women. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that is an estrogen receptor antagonist in breast tissue and an agonist in other tissues, including bone and uterus. Estrogen receptor (ER) status strongly predicts response to tamoxifen therapy, with a 31% reduction in the annual breast cancer death rate in ER-positive patients and no effect on patients with ER-negative disease. For postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitor therapy, either alone or given sequentially with tamoxifen, has been shown in multiple clinical trials to be superior to tamoxifen therapy alone.

HER-2 Status

HER-2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Approximately 18% to 20% of breast cancer patients overexpress the HER-2 protein. Older women are less likely to express HER-2 than younger women. HER-2 expression predicted poor cause-specific survival in both older and younger women prior to the use of trastuzumab, an anti-HER-2 antibody. The benefit of trastuzumab is confined to those patients with immunohistochemically confirmed overexpression of HER-2 or fluorescence in situ hybridization-confirmed elevated gene copy number of HER-2/neu.

Histology and Grade

Grade has been described earlier and represents a composite evaluation of the tumor’s aggressiveness by histologic criteria. Grade is a well-established predictor of outcome. Older patients tend to present with breast cancer with lower proliferative rates and lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion, both markers of less aggressive behavior. Breast cancer may present with variable histologic patterns, and these histologic subtypes may have different clinical behavior. Approximately 75% of women with invasive breast carcinoma, a cancer of epithelial cell origin, have infiltrating ductal type carcinoma. Patients who have a component of invasive lobular carcinoma frequently present at a more advanced stage than those with purely infiltrating ductal carcinoma, and their tumors are more likely to be hormone-sensitive.

Hormone Receptor Status

The expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors on the surface of breast cancer cells is both prognostic and predictive of response to hormonal therapy. Collectively, patients who are either estrogen- and/or progesterone-receptor positive live longer than patients whose tumors are hormone receptor-negative. This association holds true after accounting for age, stage, histology, and other demographic variables. The association is also maintained in both older and younger women. Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) that is an estrogen receptor antagonist in breast tissue and an agonist in other tissues, including bone and uterus. Estrogen receptor (ER) status strongly predicts response to tamoxifen therapy, with a 31% reduction in the annual breast cancer death rate in ER-positive patients and no effect on patients with ER-negative disease. For postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitor therapy, either alone or given sequentially with tamoxifen, has been shown in multiple clinical trials to be superior to tamoxifen therapy alone.

HER-2 Status

HER-2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein receptor of the epidermal growth factor receptor family. Approximately 18% to 20% of breast cancer patients overexpress the HER-2 protein. Older women are less likely to express HER-2 than younger women. HER-2 expression predicted poor cause-specific survival in both older and younger women prior to the use of trastuzumab, an anti-HER-2 antibody. The benefit of trastuzumab is confined to those patients with immunohistochemically confirmed overexpression of HER-2 or fluorescence in situ hybridization-confirmed elevated gene copy number of HER-2/neu.

Overall Prognosis

The overall prognosis of elderly women with breast cancer is the net effect of the biology of the tumor and the efficacy and tolerability of therapy. The overall prognosis of older women has been reported in some studies to be comparable to the prognosis for younger women and in other studies to be worse than the prognosis for younger women. Differences in receipt of adjuvant therapy likely contribute to these disparate results. In a study of 407 women aged 80 years or older who were treated during the 1990s, 12% received no therapy; 32%, tamoxifen only; 7%, breast-conserving therapy only; 33%, mastectomy; and 14%, breast-conserving therapy with adjuvant radiation therapy. The 5-year breast cancer specific survival for these groups were 46%, 51%, 82%, and 90%, respectively. Age was strongly associated with less-aggressive treatment after controlling for tumor type, general health status, and comorbidities.

Adjuvant Therapies: Radiotherapy

Adjuvant radiotherapy may be used in two settings: after breast-conserving therapy and after mastectomy. A review of almost 50,000 women age 65 or older treated for breast cancer in the 1990s found that approximately 76% of the patients who had lumpectomies also had radiation therapy. Receipt of postlumpectomy radiation therapy was associated with later year of diagnosis, younger age, fewer comorbidities, nonrural residence, chemotherapy, white race, and no prior history of heart disease. Older age has also been associated with longer delay between lumpectomy and radiation therapy. In a randomized trial of 636 women older than 70 years with small, node-negative, ER-positive breast cancer who were assigned to either BCT with tamoxifen and radiotherapy or BCT with tamoxifen only, found that risk of local relapse was increased at 5 years, from 1% to 4% without radiation; however, survival was not significantly different between the groups.

Adjuvant Therapies: Systemic

Chemotherapy

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends adjuvant chemotherapy for all patients less than 70 years old with nodal involvement or with tumors larger than 1 cm. The guidelines recommend consideration of chemotherapy for patients with tumors between 0.6 and 1 cm after evaluation of hormone receptor status, HER-2 status, and other unfavorable features including angiolymphatic invasion, high nuclear grade, or high histologic grade. Common chemotherapeutic drugs used include doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, paclitaxel, and docetaxel. A meta-analysis of 194 randomized trials of adjuvant chemotherapy begun by 1990 found that anthracycline-containing compounds reduced the annual breast cancer death rate by 38% in patients younger than 50 years, and by 20% in patients aged 50 to 69. Few patients older than 70 were included in these trials. Another meta-analysis established the survival benefit of adding a taxane to anthracycline chemotherapy, regardless of patient age. In a dose-dependent fashion, anthracycline chemotherapy is associated with development of cardiomyopathy in elderly patients with hypertension. In an effort to avoid the anthracycline toxicity, docetaxel and cyclophosphamide were compared to doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide for the treatment of early breast cancer. Sixteen percent of the trial participants were age 65 or older and, after 7 years of follow up, both disease-free survival and overall survival were better in the docetaxel/cyclophosphamide arm.

In a single institution study of more than 1500 women aged 55 or older treated for breast cancer between 1997 and 2002, older age was a significant predictor of not receiving chemotherapy when indicated by guideline recommendations. This association remained after controlling for confounding factors such as stage, tumor characteristics, comorbidity score, and other demographic variables. To assess the toxicity of chemotherapy for older patients in the community, one analysis of SEER-Medicare data from 1991 to 1996 found that the hospitalization rate for chemotherapy complications was 9%, which increased with increasing stage of cancer and increasing comorbidities, but did not differ by age category. An evaluation of data from four randomized trials of adjuvant therapy that compared a higher dose or more intense chemotherapy regimen with a lower dose or less intense regimen suggested that more chemotherapy was associated with longer disease-free and overall survival. There was no association between age and disease-free survival. Older patients had more non–breast cancer-related deaths.

Molecularly Targeted Therapy

Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against the HER-2/neu receptor, is recommended for use in patients with HER-2/neu overexpression or gene amplification and tumors larger than 2 centimeters or lymph node involvement who are receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. The benefit of trastuzumab was established in a combined analysis of two randomized trials that demonstrated a 33% decreased risk of death among patients who received trastuzumab. Trastuzumab is typically started either with or after chemotherapy and continued weekly to complete 1 year of therapy. Major toxicities of trastuzumab include cardiomyopathy, allergic infusion reactions, and variable pulmonary toxicities. Data on the use of trastuzumab in elderly patients are limited, but suggest that efficacy and toxicity are similar in all age groups.

Hormonal Therapy

The goal of hormonal therapy for breast cancer is to reduce estrogen stimulation of the tumor. Three major modalities are used to reduce estrogen stimulation: ovarian ablation, by oophorectomy, with radiation, or by chemical means with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH); estrogen receptor blockade by a partial agonist (tamoxifen); and blockade of peripheral estrogen production by an aromatase inhibitor, in women without functioning ovaries. A meta-analysis of the effects of hormonal therapy in randomized trials of more than 60,000 patients demonstrated that for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, tamoxifen therapy for 5 years reduced the annual breast cancer death rate by 31% over 15 years, irrespective of patient age. Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) decrease conversion of androgen precursors into estrogens, and have been shown to be superior to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women in a number of large randomized trials. AIs are less likely to cause venous thromboembolic events and endometrial cancer, but are more likely to result in arthralgias and accelerated bone loss. Aromatase inhibitors are now recommended by the NCCN as first-line hormonal therapy for postmenopausal women. Subgroup analyses of the older patients in the aromatase inhibitor trials confirm that AIs have similar efficacy and toxicity in older and younger postmenopausal patients. A review of more than 1500 breast cancer patients treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1997 and 2002 noted that, after accounting for comorbidities and stage, among only patients with good performance status, in situations where guidelines recommended hormonal therapy, women aged 75 and older were 90% less likely to be treated with hormonal therapy than women aged 55 to 64. Challenges to the effective use of adjuvant hormonal therapy include poor compliance and high cost.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree