Chapter 17

Acute kidney injury and metabolic emergencies

Although specific management of metabolic disturbances and acute kidney injury in the older adult does not differ hugely from the younger patient, these conditions are increasingly common, and often co-exist with other acute and chronic illnesses, complicating management. Metabolic disturbances may present with non-specific symptoms and signs and can be easily missed if blood tests are not undertaken. The workup and treatment of all metabolic disturbances in older patients should be modified according to the patient’s other comorbidities, prognosis and goals of care.

Acute kidney injury

Acute kidney injury (AKI) commonly complicates acute illness in older adults, occurring in 15% of adult hospital admissions. Patients over the age of 70 have a 3.5-fold increase in AKI (1), with advancing age an independent risk factor. AKI is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with impaired recovery of renal function in older adults (2). As AKI is a biochemical diagnosis, often with no symptoms and signs, a high degree of vigilance is required.

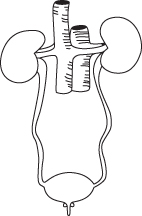

| Decrease in the number of functional nephrons. Reduced tubular conservation of sodium and water during periods of dehydration, increasing the risk of volume depletion. Decreased capacity for the excretion of drugs and drug metabolites. |  Figure 17.1 Structural and functional changes in the aging kidney reducing renal reserve (3). | Autoregulation of renal blood flow is less effective leading to lack of glomerular filtration rate preservation in dehydration states. Ageing of systemic vessels results in decreased renal blood flow and a rise in renal vascular resistance. There is a variable reduction in glomerular filtration rate with age. |

Definition

AKI is typically identified by an increase in serum creatinine levels or a reduction in urine output. A number of different criteria for diagnosis and staging of AKI are in use such as the RIFLE, AKIN or KDIGO definitions (4–6). Box 17.1 outlines the criteria suggested by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (and based on the above definitions) for the detection of AKI.

These criteria have limitations in the older patient. In many cases, previous blood results may not be available for comparison, and decreased muscle mass with ageing may lead to seemingly reassuring creatinine levels. Fifty percentage of renal function may be lost before serum creatinine rises, delaying recognition of AKI (8).

Background

Structural and functional changes occur in the ageing kidney, in part due to hypertension and other comorbidities as well as the ageing process itself (Figure 17.1). These changes increase susceptibility to AKI due to the combination of a precipitating illness with comorbid conditions, nephrotoxic medications, contrast agents and urinary obstruction due to prostatic enlargement.

Initial assessment

Assess airway, breathing and circulation. Record vital signs and examine to determine the patient’s volume status—fluid resuscitation may be required immediately. Exclude life-threatening complications of AKI as illustrated in Box 17.2 and involve critical care early if necessary.

History and examination

AKI can be classified according to its cause: pre-renal (33% of cases in older adults), renal (58% of cases) or post-renal (9% of cases) (9). Table 17.1 highlights these causes and points to note on history and examination.

Table 17.1 History and examination in pre-renal, renal and post-renal causes of acute kidney injury (1)

| Causes | History | Examination | |

| Pre-renal Decreased renal perfusion | Fluid loss or redistribution | Vomiting, diarrhoea, haemorrhage, diuretics, osmotic diuresis due to hyperglycaemia and sepsis | Signs of volume depletion |

| Decreased cardiac output | Heart failure, arrhythmias and valve disease | Evidence of cardiac failure | |

| Impaired renal autoregulation | Medications: non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers | ||

| Renal Intrinsic renal damage | Acute tubular necrosis | Sepsis, prolonged volume depletion, recent administration of radio-contrast material, chemotherapy and rhabdomyolysis | Signs of sepsis or source of infection |

| Vascular | Recent angiography causing cholesterol embolisation | ||

| Glomerulonephritis | Possible history of autoimmune disease or vasculitis | ||

| Acute interstitial nephritis | Infection, new medication e.g. antibiotics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories | ||

| Post-renal Obstructive | Upper urinary tract | Renal and ureteric stones, pelvic malignancy and retroperitoneal disease | Renal angle tenderness and pelvic masses |

| Lower urinary tract | Prostatic cancer or hypertrophy, prolonged urinary retention, bladder stones and urethral strictures | Acute urinary retention, enlarged prostate on rectal examination |

The history should establish any risk factors for AKI, such as recent medication change, recent illness with associated dehydration, reduced fluid intake (e.g. due to delirium), radiological imaging, surgical procedures and other comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. Older patients are often unaware that they have chronic kidney disease, even if this has been identified previously.

Investigations

Blood tests

Urgent urea, creatinine and electrolytes as well as a venous or arterial blood gas will indicate the severity of acute kidney injury and demonstrate any serious complications such as metabolic acidosis or hyperkalaemia (Box 17.2).

Other investigations will depend on the likely cause.

Bedside bladder scanning

This can be performed rapidly at the bedside to exclude urinary retention.

Urinary tract ultrasound

Urinary tract ultrasound should be considered in patients with a possible obstructive cause and may demonstrate hydronephrosis or ureteric dilatation. Small kidneys on ultrasound may indicate pre-existing chronic kidney disease, although reduced renal mass may be due to ageing alone.

Urinalysis

Urine dipstick may reveal blood or protein suggestive of a renal cause. Urine should be sent for microscopy to look for casts suggestive of acute tubular necrosis or glomerulonephritis. White blood cells in the urine may suggest interstitial nephritis in the absence of other signs of infection. Renal biopsy may be indicated to confirm diagnosis.

Urinary electrolytes

Urinary electrolytes may help in identifying pre-renal causes of AKI, where renal tubules retain sodium and water, resulting in low urinary sodium and osmolality. This may be less useful in the older patient due to reduced sodium-conservation ability and diuretic use.

Management

General management of AKI should involve careful monitoring of vital signs, fluid balance and treatment of the underlying cause. Blood pressure and oxygenation should be optimised. Careful medication review is required to stop or suspend nephrotoxic drugs or drugs causing dehydration. Doses of several other drugs need to be adjusted in AKI, or alternative drugs with no or fewer renally excreted metabolites selected: consult a pharmacist or other specialist.

Repeated creatinine and electrolytes are necessary to assess progress and detect complications. In more serious cases, catheterisation with careful monitoring of urine output, high dependency care and/or invasive monitoring may be required.

Specific management of AKI will depend on the likely aetiology, as given in Table 17.2.

Table 17.2 Treatment of AKI depending on cause

| Cause | Treatment strategy |

| Pre-renal | Volume repletion with intravenous crystalloid Stop diuretics and antihypertensive medication Optimise cardiac output and oxygenation |

| Renal | Stop nephrotoxic medication Avoid or delay radiographic contrast use Consider specific treatment e.g. steroids for glomerulonephritis |

| Post-renal | Catheterisation Nephrostomy or ureteric stenting if higher obstruction is present |

Complications

Full access? Get Clinical Tree