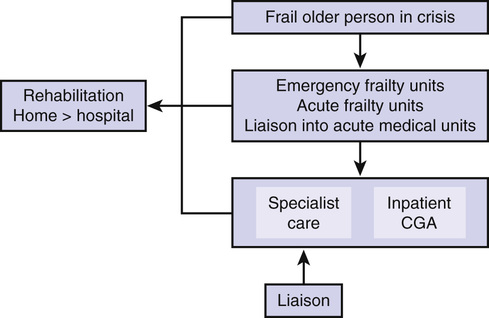

Simon Conroy Hospitalization of an older adult can be a sentinel event that heralds an intensive period of health and social care service use.1–3 This is especially the case for frail older adults—here referring to people with multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, often cognitive impairment (delirium and/or dementia)—many of whom present nonspecifically. Such patients are not always well served by the increasingly specialized, protocol-driven care provided in acute hospitals, but can benefit more from a more nuanced and holistic approach to their care. The literature on acute care of (frail) older adults points toward comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) being more effective than usual care.4–6 This chapter will offer examples of why CGA might work in the acute care context, critique the evidence base, and finally describe a systems-based approach to the care of frail older adults in acute hospitals. CGA is defined as “a multidimensional, interdisciplinary diagnostic process to determine the medical, psychological, and functional capabilities of an older person in order to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and long-term follow-up.”7 Why this is important will be addressed in this section. This highlights the importance of taking a holistic overview. In this cohort of patients, it is not sufficient to focus simply on one domain. For example, an approach to chest pain that simply states that the troponin level is negative and a coronary angiogram is not required, but fails to test for and identify the cognitive impairment that led to the individual not taking analgesia for arthritis (the true cause of the pain), is doomed to fail. Also, a purely functional approach to falls that seeks to provide only rehabilitation and not identify the underlying reasons for a fall, of which there are many, including serious disorders such as aortic stenosis, will not succeed. It is the integrated assessment of all the domains of the CGA that allows an accurate problem list to be generated. In a mature CGA service, the hierarchy should be flattened so that all staff members should feel empowered to put forward a constructive challenge within and without their particular area of expertise. For example, the option to admit for rehabilitation by a therapist concerned about falls at home might be challenged by pointing out that admission often increases the risk of falls and that home-based rehabilitation may offer substantial benefits.8 Equally, therapists will bring useful information to the diagnostic process; for example, the patient who is fit to return home but develops new dyspnea on mobilization might prompt a reevaluation of respiratory function and identify potentially new diagnoses, such as pulmonary embolus. That this assessment is a process and not a discrete event is also key; the process should continue in an iterative manner over the course of the acute stay, and the diagnostic elements should be sensitive to deviations from the anticipated pathway. For example, if the initial treatment plan for an older adult with a fall and hip pain but no fracture was to “increase analgesia, reduce antihypertensives, and aim to return home once able to walk 5 m unaided using a frame,” yet after 14 hours, pain remains a problem, the diagnosis may need to be revisited and further imaging considered. This reinforces the idea that the team caring for an older adult needs to know and respect each other’s roles and know and understand what each is doing, and understand how medical treatment will affect the rehabilitation goals, and vice versa. For example, although therapists would not need to know the detailed intricacies of the management of acute heart failure, it is important that they know that intravenous diuretics might be required for the first few days and result in polyuria and then be able to incorporate continence needs into the rehabilitation plan. Similarly, physicians will need to appreciate that just because a patient has grade 5 power on the Medical Research Council (MRC) grading system, this does not necessarily translate into useful functional ability. Because many older adults have multiple long-term conditions, they usually require some form of ongoing care and support. How this is delivered will vary among regions worldwide, but there is little point in providing excellent acute care if conditions are only going to be allowed to decline because of a lack of ongoing support. For example, a 2-week admission, during which Parkinson disease medications are carefully titrated and optimized in conjunction with the multidisciplinary rehabilitation process, can easily be reversed if there is no ongoing titration of L-dopa once the patient returns home. So, while integrating the standard medical diagnostic evaluation, CGA emphasizes problem solving, teamwork, and a patient-centered approach. Multiple systematic reviews have suggested that discrete units or wards are more effective than a dispersed or liaison-type service; the most recent reviews on liaison services offering CGA suggest limited or no effect in acute care.9,10 However, the trials used in the Ellis meta-analysis that led to this conclusion are somewhat dated, with the most recent being reported in 2007. In the more recent review on liaison services, Deschodt and colleagues10 reported on studies up until 2012 in a range of settings, but also found limited evidence of benefit from liaison services. The perceived wisdom is that liaison services are thought to be less effective because there is less control over the care that patients receive.11 This has been supported by process evaluations that indicate that only about two thirds of all recommendations are implemented.12 It is equally possible that usual care is improving, reducing the absolute benefit from CGA, and it is noteworthy that the United Kingdom’s Future Hospitals Commission has emphasized generic care over geriatric care.13 This raises some important issues. Do you need a geriatrician to deliver CGA or just the geriatric competencies applied well? The only logical answer is that it is the application of the competencies that is key, not who applies them. As Coni noted, “Geriatrics is too important to be left to geriatricians. We are all geriatricians now, and geriatric medicine should be like a caretaker government-self-appointed to instruct others how to do it, and then to preside over its own demise.”14 However, at the heart of this, is the difference between knowing and doing. Most physicians are taught the principles of geriatric medicine,15 but not all practice them. This has been suggested in more recent service developments, in which geriatric medicine is incorporated into the care of frail older adults in new settings.16–18 Surely, if usual care were so good at providing geriatric competencies, wouldn’t such service developments show limited benefit? Where resources permit, it seems sensible that conventional CGA services focus their efforts on frail older adults. This would mean streaming patients into dedicated services and ensuring that they are vertically integrated, which requires simple, clear, and locally acceptable criteria for defining frail older adults. Ideally, these criteria can be applied quickly in the emergency department or acute medical unit so that patient streaming can occur as soon as possible. It also requires CGA to be delivered at each stage of the patient journey—including the emergency department, acute medical unit, base ward, and rehabilitation setting—with the opportunity to transfer into community services at each point, where CGA should also be available (Figure 118-1).

Acute Hospital Care for Frail Older Adults

Introduction

Why Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment Works in Acute Care

Multidimensional Process

Interdisciplinary Diagnostic Process

Coordinated and Integrated Plan for Treatment

Follow-Up

How Should Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment be Delivered in Acute Care?

What Does the Evidence Suggest?

Establishing Integrated Pathways

Vertical Integration.