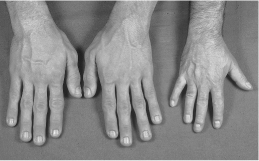

Figure 15.1 Acromegalic hands and a normal hand for comparison.

Investigations

Measurement of random GH has little value in the diagnosis of acromegaly. This is because GH secretion is pulsatile and the pulses are separated by long periods during which GH may be undetectable. In addition, GH secretion may be stimulated by a variety of factors such as short-term fasting, exercise, stress and sleep.

IGF-1 levels do not fluctuate widely throughout the day and are almost always raised in patients with acromegaly, except in severe intercurrent illness. A patient with a normal serum IGF-1 is unlikely to have acromegaly. However, IGF-1 levels may be decreased by malnutrition and liver disease (as the liver is the source of 75% of plasma IGF-1).

Like IGF-1, serum IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) secretion is GH dependent, and IGFBP-3 levels are elevated in acromegaly. However, there is considerable overlap of IGBP-3 values between those with acromegaly and normal persons.

If serum IGF-1 concentration is high (or equivocal), serum GH should be measured after a 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). In normal individuals, GH levels fall following oral glucose. Acromegaly is diagnosed when there is a failure of GH suppression to less than 1 μg/L. False-positive results may be seen in anorexia nervosa or malnutrition, adolescence, chronic liver and renal failure, diabetes mellitus and opiate addiction.

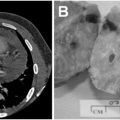

When acromegaly is biochemically confirmed, a pituitary MRI should be performed to determine the presence of a pituitary adenoma and whether there is suprasellar extension or invasion of the cavernous sinus by the tumour.

If the pituitary MRI is normal, a chest and abdominal computed tomography scan and serum GH-releasing hormone measurements may be performed to look for an extrapituitary cause. However, these are extremely rare.

Once diagnosis is established, patients should have:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree