Fig. 13.1

Example of treatment pathway in cancer

13.2 Access to Cancer Care

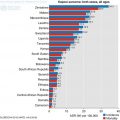

Access to cancer services although generally poor, is variable across the region. Barriers to access could be due to availability, accessibility, affordability or even acceptability (Peters et al. 2008). Most countries fail to meet the high demand of services due to complex economic and financial dynamics. Some countries have low level of investment in the public health sector which has direct impact on availability of infrastructure, resources and ability to deliver comprehensive services. Even when access to care is better, most households live below poverty line and cannot afford treatment. Level and quality of services is variable and cost of treatment likely to be high resulting in out of pocket payment. The average out of pocket expenditure in Sub Saharan Africa for private health is between 40% and 50%, with Nigeria being highest at 95.8% according to the 2013 data from World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS). Some countries like Botswana and South Africa, where government have made significant investment in health, out of pocket expenditure is less than 20%; making health care more accessible when compared with other regions. Geographic accessibility is another major challenge for patients living in remote areas especially when transport infrastructure is lacking. This can lead to abandonment of treatment with significant impact on survival. Therefore governments need to proactively find ways to meet supply and demand in order to improve access to cancer care.

WHO describes a robust health system as being the one that has the following six building blocks: (http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/health_systems_framework/en/) leadership/governance; health care financing, health workforce, medical products and technologies, Information and research and service delivery. Although removal of financial barriers is not the only factor which might ensure access to good health care, it will definitely contribute to reduction in disparities which currently exist.

13.2.1 Financing Public Health

To remove user fees, governments have to improve financial strategies to successfully invest in the health system. Other countries have started taxing products known to damage health e.g. tobacco and petroleum industries (http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/Act83of1993.pdf). Another strategy would be prepayment method, whereby public health insurance is made available to all: Rwanda’s community based health insurance (CBHI) is a stratified scheme which takes in to account people of low income, whose payments are subsidised by government and development partners (http://www.who.int/bulletin/africanhealth2014/improving_access_to_health_care/; Nyinawankusi et al. 2015). This scheme was initially voluntary with poor uptake of 7% in 2003. However by 2010, 91% of population had been enrolled. It is complimentary to existing social insurance schemes and private health insurances within the country, and beneficiaries pay about 10% the total CBHI bill at the time of presentation. This scheme is supported by WHO and has encouraged the concept of universal health coverage but is yet to be implemented in most Sub Saharan countries. To ensure quality outputs, result based financing for health care providers may need to be implemented. In 2006 Burundi introduced fee exemptions for pregnant women, resulting in high utilisation of the service but due to persistent underfunding, quality of service was compromised (Musagno and Ota 2015). In 2008, result based financing pilot was introduced whereby health providers received bonuses for both quantity and quality of service delivered. There was notable improvement for each indicator monitored as a result, the scheme was launched nationally.

South Africa is making plans to introduce national health insurance over the next 14 years with similar goals of equal access to affordable health care, financial risk protection, covering a comprehensive range of services from primary health care to specialist treatment (Naidoo 2012; http://www.health-e.org.za/2015/12/14/white-paper-national-health-insurance-for-south-africa/). The scheme is to be delivered in such a way that it will modify provider costs and ensure delivery of quality service through accreditation of providers. Evidence based treatment guidelines will be followed and cost effective interventions implemented.

The system of Universal health coverage is encouraging but has to be adapted to individual countries and requires extensive monitoring. Such a system is likely to encourage attendance of screening programmes and improve early detection of cancer, with potential reduction in morbidity and mortality. To ensure delivery of high quality service, key performance indicators for health providers need to be set and regular national audits undertaken. Result based financing is one way of implementing this and will require strong leadership and robust governance framework. This will also ensure efficient use of resources and discourage waste or abuse. Prioritisation of services, establishment of integrated outreach services coupled with community education and participation is likely to improve access to care which will in turn influence health outcomes. Better public-private collaborations, engagement of national and international organisations (academia and non-academic) are required to be able to deliver the care required.

13.2.2 Collaborative Programmes

AMPATH-Oncology is a good example of Low and high income country collaboration which started as an HIV programme, and later evolved into a cancer care programme (Strother et al. 2013). Through this collaboration, further infrastructure to provide cancer care in Kenya was developed, including development of core services to support research and standardised protocols. They were also able to provide expertise, training and education, drugs, and help develop a care model for the available resources. In isolation, such partnerships are not able to meet the high demand of services but can help model ways to improve access to cancer care within resource constrained countries, at the same time demonstrating the importance of the building blocks required for a robust health system. Support from national governments is imperative for sustainability of such programmes, which can be used as foundation for developing comprehensive services.

13.3 Cancer Infrastructure

Poor availability of infrastructure is another hurdle to be addressed in order to successfully deliver chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Information on available cancer centres in Sub Saharan Africa is limited. Review article by Dr. Stefan published in Journal of Global Oncology (2015) reports 102 cancer centres in Africa, 38 of which are located in South Africa (Stefan 2015b). Deficiency of specialist centres would limit delivery of complex regimes and contribute to poor outcomes. Development of these centres particularly government supported institutions, is critical as they will act as reference point for national cancer control plans and can provide patient care, training, continuing professional development, research, cancer prevention, community outreach, and international partnerships.

13.3.1 Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy units are integral to delivery of comprehensive cancer care. Scarcity of resources in some parts of the region means chemotherapy is delivered in general wards, by untrained personnel, with weak governance structure. In countries like South Africa where cancers services are much better developed, chemotherapy units are able to deliver complex regimes but discrepancies still exists with regards to quality and availability within the region. Mahlangu et al. recently conducted a survey of resources in South Africa, demonstrating disparities and resource availability (Mahlangu et al. 2016). Fifty percent of responders were private; almost a quarter were public, whilst the remain quarter worked for both. Most of the providers were open Monday to Friday for a full day and less than 10% were able to provide service over the weekend. Thirty three percent report dysfunctional infrastructure with about 30% reporting inadequate diagnostic radiology and laboratory services. Only 20% had more than 10 rooms available for clinical examination. Although 90% (90/101) could provide outpatient chemotherapy, facilities for high dose chemotherapy were variable (see Fig. 13.2). Just over 70% are able to deliver high dose chemotherapy, whilst the remaining 27% do not have the necessary facilities. Of the seventy three, on 21 could provide the service to at least a third of their patient population.

13.3.2 Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is required in more than 50% of malignant tumours and is an essential component in cancer treatment pathway in both curative and palliative setting (Delaney et al. 2005). It is estimated that 40% of patients cured from cancer require radiotherapy; unfortunately access remains poor in most Sub Saharan countries despite increase of radiotherapy equipment over the last decade. Information on radiotherapy services as documented in the directory of radiotherapy services (DIRAC) database is only available in less than 50% of the countries and there are significant regional disparities as listed in Table 13.1 (DIRAC 2016). The southern part of Africa has invested more in radiotherapy services compared with the rest of the Sub Saharan region. Access and availability of equipment is also variable across the region, with most having the most basic forms including two dimensional planning systems and few having modern facilities which are able to deliver intensity modulated therapy. In some parts of the region, delivery of treatment has been carried out without adequate planning systems.

Table 13.1

DIRAC data 24th March 2016

Region | Countries | RT centres | Linac | Co60 | CT | Simulator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

East Africa | 4 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

West Africa | 5 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

Central Africa | 4 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

Southern Africa | 4 | 49 | 75 | 11 | 34 | 15 |

In 2013, Abdel Wahab et al. published a comprehensive review of radiotherapy services in Africa (Abdel Wahab et al. 2013). North America and Western Europe had capacities of 14.89 and 6.12 teletherapy machines per million people compared to average of less than one machine per million people for the whole of Africa. In most African countries there was a big gap between availability and need. Mauritius, South Africa, Tunisia and Egypt had highest capacities of 2.36, 1.89, 1.55, 0.9 teletherapy machines per million people respectively. Countries like Ethiopia and Nigeria had 0.02 and 0.05 machines per million people, respectively. Brachytherapy resources were also variable, with a serious shortage in most of central and East Africa considering the high incidence of cervical cancer throughout the region. Maintenance and replacement of available equipment was another important contributing factor to the shortage. Cobalt 60 machines which deliver lower energy compared to Linear accelerators are less expensive and easier to manage as they do not require extensive investment with respect to infrastructure, maintenance and quality control. They need to be replaced every 5–7 years, however about half of the available units at the time of the analysis were older than 20 years. In low income countries, these machines remain a viable option and can provide effective clinical therapy with appropriate planning and treatment delivery.

Regional design of radiotherapy services should be informed by analysis of data from national cancer registries according to specific tumour incidences, allowing calculation for demand (International Atomic Energy Agency 2010). Radiation utilisation rate (RUR) which is the proportion of a specific population of patients with cancer that receives at least one course of radiotherapy during their lifetime calculated as:

Can be also be used to obtain practical estimate of the demand of radiotherapy service under ideal conditions, including optimal number of radiotherapy fractions per cancer patient and treatment cost. It can also be used as a tool to predict future radiotherapy workload and aid service planning. RUR per tumour site is variable globally and depends on national cancer plans. Analysis of four high industrialised countries (Sweden, Netherlands, Australia, USA) was variable and optimal RUR percentage for all tumour types except skin was 52%, which means it is likely to be higher in low income countries were prevention and early detection programmes are still weak (International Atomic Energy Agency 2010).

WHO stepwise framework (Table 13.2) for developing radiotherapy services is adaptable to various countries and includes assessment and implementation phases with short, medium and long term goals (WHO 2008). Atun et al. reports potential positive economic benefits if countries are willing to invest in radiotherapy services (Atun et al. 2015). The projected benefit was seen across all economic systems (high and low income countries). Using efficiency models, they projected that between 2015 and 2035 scale up of radiotherapy services will costs about $14.1 billion in low-income, $33.3 billion in lower-middle-income, and $49.4 billion in upper-middle-income countries—a total of $96.8 billion; and could lead to saving of 26.9 million life-years in low-income and middle-income countries over the lifetime of the patients who received treatment. Therefore, it is imperative that governments prioritise cancer action plans not only for potential socioeconomic benefit but to avert future crisis.

Table 13.2

Developing a radiotherapy strategy applying the WHO stepwise framework

Time period | Core | Expanded | Desirable |

|---|---|---|---|

With available resources | With a projected increase | When more resources are available | |

Short term 0–5 years | Streamline referral Patterns increase machine efficiency Increase staff training and capabilities Install information technology to monitor deficiencies Stimulate cooperation and sub-specialization | Increase the number of machines Increase staff numbers Increase training of staff National audit of radiotherapy by an embedded IT system Invest in specific specialist services Invest in health delivery research | Create new networks of interlinked radiotherapy centres Develop international links for training and audit

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|