Chapter 15

Abdominal emergencies

Introduction

Abdominal pain is the fourth commonest presentation to the Emergency Department in the older adult. It is a worrisome symptom, associated with a mortality rate of 5–10% (1). Abdominal pain may be minimal or even absent in the older patient despite the presence of serious intra-abdominal pathology. Vomiting, change in bowel habit, gastrointestinal bleeding, urinary symptoms or non-specific presentations such as delirium or immobility may predominate.

Identifying the cause of abdominal symptoms can be difficult due to the frequency of atypical presentations, comorbid conditions and sometimes limited history due to cognitive impairment. The wide range of potential differentials leads to misdiagnosis occurring in up to 30% of cases (2). The older patient may initially appear well with normal vital signs despite serious underlying pathology. Early abdominal CT is often helpful in reaching a diagnosis (3), but caution must be taken when using IV contrast in dehydrated patients (Chapter 2). Many older people will have radiological evidence of gallstones or diverticular disease without these necessarily being the cause of their symptoms. Early, effective analgesia is vitally important in managing the older person with abdominal pain (Chapter 3). Gastrointestinal bleeding increases in incidence with age, partly due to the more widespread use of anti-platelet agents in the older person. Prompt resuscitation and early endoscopy are required in the older patient due to the increased mortality risk. Up to 30% of older adults admitted with abdominal pain undergo surgery (4). The mortality rate for emergency abdominal surgery in older adults is 15–34%, predominantly due to complications arising from coexisting disease (5).

Background

Age-related changes in the gastrointestinal system are shown in Figure 15.1. Biliary disease is the responsible for 20–30% of cases of abdominal pain in the older patient, followed by bowel obstruction, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), diverticulitis and appendicitis. In 20% of cases, no diagnosis is made by the time of discharge.

| Decreased gastric emptying, atrophy of gastric mucosa and rise in carriage of Helicobacter pylori increases the likelihood of peptic ulcer disease, gastritis and reflux. Acid production may increase. Immobility significantly prolongs colonic transit time, increasing risk of constipation or post-operative ileus. Slower colonic transit with increased water re-absorption results in harder faeces, exacerbating constipation and causing faecal impaction and formation of diverticulae. | Increasing laxity of gastro-oesophageal sphincter may lead to hiatus herniae and reflux symptoms. Figure 15.1 Age-related change in the gastrointestinal system. | Changes in bile salt composition and decreased responsiveness to cholecystokinin with depressed gallbladder motility predispose the older patient to gallstone formation. Approximately 20% of 70 year olds and 40% of 80 year olds will have gallstones. Atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease increase the risk of vascular causes of abdominal pain in the older adult such as mesenteric ischaemia and abdominal aortic aneurysm. |

| Two-thirds of older adults have incidental colonic diverticulae that may or may not develop complications. |

Initial assessment

An older patient presenting with abdominal pain should be assessed promptly (Box 15.1) to exclude life-threatening causes such as acute myocardial infarction or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

History

Once it is clear from the initial assessment that the patient is stable, a pain history should take place, incorporating the mnemonic SOCRATES (Table 15.1). Altered pain perception in the older adult and cognitive impairment may affect the ability to report and describe pain (Chapter 3).

Table 15.1 Points to cover in an abdominal pain history

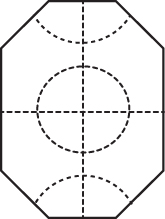

| Site | Figure 15.2 illustrates sites of abdominal pain and potential underlying causes. The older patient is less likely to identify a precise area of pain. Back pain may originate from retroperitoneal structures such as the aorta and kidneys |

| Onset | Sudden onset of pain may indicate a ruptured viscus or ruptured aortic aneurysm. However, even abdominal catastrophes such as a perforated peptic ulcer may be associated with insidious onset of symptoms |

| Character | Establish whether pain is dull and aching indicating visceral pathology or sharp and localised indicating peritoneal irritation |

| Radiation | Radiation to the back may be characteristic of pancreatitis, peptic ulceration or aortic aneurysm. Ureteric calculi typically cause flank pain radiating to the groin. Diaphragmatic irritation may cause pain referred to the shoulder |

| Associated symptoms | Establish any additional features:

Other important subacute symptoms include weight loss, dysphagia, early satiety, fatigue and change in bowel habit, which may point to abdominal pain as a result of an underlying malignancy |

| Timing | A history of recurrent pain episodes should prompt consideration of mesenteric ischaemia, biliary disease, ureteric colic or malignancy. Persistent or worsening pain is usually more concerning than pain that has improved spontaneously |

| Alleviating and aggravating factors | Pain with movement, coughing or deep breathing may indicate peritoneal irritation. Pain after eating may reflect peptic ulcer disease, biliary disease or mesenteric ischemia |

| Severity | Pain in the older adult is often reported as less severe for any given pathology. Mild pain should not dissuade the clinician from considering a serious underlying cause |

Past surgical history should include past operations, their indications and any complications. Past medical history should include risk factors for vascular causes including cardiovascular disease, smoking, atrial fibrillation, or peripheral vascular disease. Diabetes may be associated with atypical presentations. Medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, anti-platelet agents, SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) antidepressants, and steroids may increase the risk of peptic ulceration and gastrointestinal bleeding. Anticoagulants may require urgent reversal where there is evidence of bleeding or surgery is required.

Examination

In addition to an abdominal examination, a cardiorespiratory examination is important to assess circulatory status and detect medical causes of abdominal pain such as pneumonia or congestive cardiac failure. Signs of chronic liver disease should be sought. The presence of atrial fibrillation should prompt consideration of mesenteric ischaemia. Postural blood pressure is useful if gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected.

Inspection

Initial inspection may reveal abdominal distension or previous surgical scars. There may be a visible hernia or mass. Rarely, bruising in the flanks may be visible in necrotic pancreatitis or ruptured AAA.

Palpation

Focal tenderness may point towards a particular aetiology, and guarding and rigidity indicates localised peritoneal irritation. However, this may be much less marked or even absent in the older patient due to reduced abdominal wall musculature and muscle fatigue. One study demonstrated that only 21% of older adults with perforated peptic ulcers presented with rigidity and guarding (6). Abdominal pain that does not worsen with palpation is typical of mesenteric ischaemia. Feel for a pulsatile mass and check the femoral and distal limb pulses, which may be absent in ruptured AAA. Take care to examine the inguinal regions and scrotum, for herniae, masses and skin changes. Figure 15.2 illustrates different sites of abdominal pain and their potential causes.

Percussion

A dull percussion note may reveal urinary retention, organomegaly or a solid malignancy. Hyperresonant percussion may reflect dilated bowel loops due to obstruction. There may be evidence of ascites in advanced malignancy or liver or congestive cardiac failure.

Auscultation

High-pitched bowel sounds may be audible in small bowel obstruction. Absent bowel sounds is a concerning sign, potentially indicating ileus due to peritonitis or severe intra-abdominal infection or inflammation.

Rectal examination

Rectal examination should be performed in most patients and may reveal melaena, rectal bleeding, faecal impaction, rectal masses or prostatic enlargement.

| Epigastric Pancreatitis Peptic ulcer disease Gastritis Myocardial Infarction Cholecystitis Right-sided Cholecystitis Pyelonephritis Pneumonia Hepatic congestion Renal colic Appendicitis Renal calculi Caecal tumour Right-sided diverticulitis |  Figure 15.2 Potential causes and sites of abdominal pain in the older person. | Left sided Pneumonia Peptic ulcer disease AAA Diverticulitis Renal calculi Colon cancer Non-specific or central Mesenteric ischaemia Small bowel obstruction AAA Malignancy Extra-abdominal or medical causes (Table 15.3) |

| Suprapubic Acute urinary retention Incarcerated inguinal hernia Gynaecological malignancy Urinary tract infection |

Investigations

An urgent blood gas, venous or arterial, may demonstrate acid–base derangement and/or an elevated lactate, which would increase concern for perforation, bowel infarction, intra-abdominal sepsis or vascular catastrophe.

Full blood count may reveal a leucocytosis but frequently conditions such as cholecystitis and appendicitis are not associated with raised or left-shifted white cells in the older patient (7). Amylase should always be checked in older patients with abdominal pain. It is frequently raised in mesenteric ischaemia or perforated peptic ulcer and pancreatitis and lipase is more specific for pancreatic inflammation. Liver function tests are often normal in acute cholecystitis, unlike in younger patients (8).

Microscopic haematuria on urine dipstick testing may signal potential ureteric colic but can also result from urethral irritation due to AAA, appendicitis or diverticulitis.

Plain radiographs may identify perforation or dilated bowel loops due to bowel obstruction. Sensitivity, however, is low and films may be normal in 40–50% of confirmed perforations.

Formal or bedside ultrasound may assist in the diagnosis of cholecystitis, biliary obstruction, appendicitis and AAA. In the latter case, ultrasound will not be able to identify whether an aneurysm is leaking, but in the setting of an unstable patient, this signals the need for immediate transfer to the operating theatre.

Abdominal CT is sensitive for diagnosing perforation, AAA, diverticulitis, pancreatitis and occult malignancy. In one study of patients aged 65 years and older with abdominal pain CT imaging lead to a change in diagnosis in 45% of cases (9). See Chapter 2 for a discussion on the risks of contrast agents in the older patient. Non-contrast CT may be a useful compromise in some circumstances.

Specific causes of abdominal pain in the older adult

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

AAAs are present in 5–9% of those over 65 years (10) and are four to five times more common in men than in women. They are most often infrarenal and may extend into the iliac vessels. Rupture of an AAA has an overall mortality rate of approximately 80% (11), with around 30–50% of patients dying pre-hospital (12). Early diagnosis and intervention to control bleeding, such as cross-clamping of the aorta or endovascular balloon placement, is required. The diagnosis, however, is often delayed or missed as AAA may mimic more benign conditions such as ureteric colic, musculoskeletal back pain or diverticulitis.

The classical presentation of a ruptured AAA includes hypotension, sudden severe abdominal or back pain, and a pulsatile abdominal mass, although this triad is present in only 25–50% of individuals (13). Tamponade of bleeding in the left retroperitoneal cavity can result in normal initial vital signs. Atypical presentations include symptoms of lumbar root compression, testicular pain and gastrointestinal bleeding in the event of an aorto-enteric fistula. Microscopic haematuria may be present in up to 87% cases of ruptured AAA, due to irritation of the ureter by the aneurysm (6).

The primary goal in ruptured AAA is control of bleeding by aortic cross-clamping or endovascular balloon occlusion; without this, resuscitation efforts are futile. If the patient is stable, CT with close monitoring will confirm the diagnosis of a ruptured AAA and identify the aortic anatomy involved to guide operative or endovascular approach. Box 15.2 summarises the initial emergency management.

Open surgical treatment of ruptured AAAs is associated with a 30–50% mortality rate (12, 14). Age and haemodynamic stability on presentation are among the most important risk factors for immediate post-operative death (15). Surviving surgery is the first step in an often lengthy critical care admission followed by rehabilitation. Up to 40% of patients will not undergo operative management because of the perceived high peri-operative mortality and poor prognosis (12). Decisions as to whether to treat the oldest old with ruptured AAA are clinically and ethically challenging and require the involvement of senior clinicians.

Biliary disease

Gallstones affect 15% of men and 24% of women by the age of 70 (16). Gallstones are frequently asymptomatic, but complications such as biliary colic, cholecystitis, cholangitis and pancreatitis occur when they obstruct the neck of the gallbladder or the common bile duct. Complications of gallstones are more common in the older population. They account for 20–30% of abdominal pain presentations to the ED and are the commonest reason for abdominal surgery in the older adult.

Biliary colic causes pain, nausea and vomiting, usually triggered by eating, and settles over a few hours with analgesia. Prompt elective cholecystectomy should be considered to prevent more serious complications and hospital admissions.

Cholecystitis is characterised by right upper quadrant tenderness, pyrexia and raised leucocytes and inflammatory markers. However, raised inflammatory markers, abnormal liver function tests and fever are absent in more than half of cases in older patients. Anorexia, nausea and vomiting may predominate in the absence of pain.

Diagnosis can be confirmed on ultrasound, which demonstrates a thickened gallbladder wall in the presence of biliary calculi. Older patients have an increased likelihood of acalculous cholecystitis, however, which is not appreciated as readily on ultrasound and is associated with a higher mortality (17). If ultrasound findings are non-diagnostic, a hepatobiliary (HIDA) scan or abdominal CT may confirm cholecystitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree