Lung cancer and bronchogenic carcinoma are malignancies originating from the airways and pulmonary parenchyma. Most (approximately 90%) lung cancers are classified as non–small cell lung cancer. This distinction carries important differences for staging, treatment, and prognosis. This article presents a review of mediastinal staging for patients with non–small cell lung cancer.

Lung cancer causes significant morbidity and mortality. Annually lung cancer claims the life of 1.2 million people worldwide, and is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women. In the United States there were an estimated 222,000 new cases of lung cancer and 157,000 deaths in 2010.

Over the last century both the absolute and relative frequency of lung cancer rose dramatically as smoking became more widespread. In the 1950s, lung cancer became the most common cause of cancer deaths in men, and in 1985 it became the leading cause of cancer deaths in women. Although lung cancer deaths have begun to decline in men, the death rate in women continues to rise, and almost one-half of all lung cancer deaths now occur in women. Lung cancer is responsible for more cancer-related deaths than the next three most common cancers combined (breast, colon, and prostrate).

Lung cancer and bronchogenic carcinoma are malignancies originating from the airways and pulmonary parenchyma. Most (approximately 90%) lung cancers are classified as non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This distinction carries important differences for staging, treatment, and prognosis. This article presents a review of mediastinal staging for patients with NSCLC.

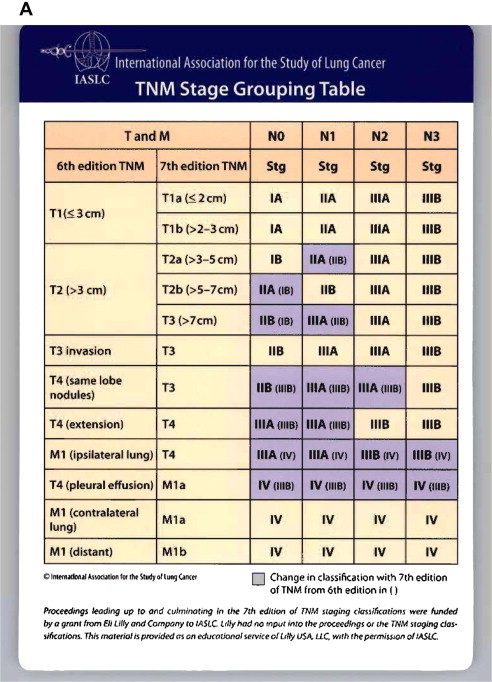

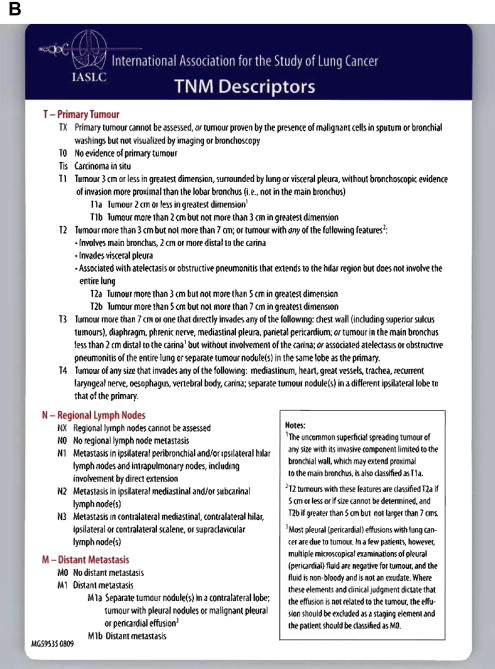

For patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer, evaluation of the mediastinum is critical because it guides treatment and predicts survival. Local disease (stages I and II) is primarily treated with surgery, whereas locoregional, locally advanced, and advanced disease are primarily treated with nonoperative modalities. In patients without evidence of distant metastatic disease the evaluation for invasion into nonresectable structures and mediastinal lymph nodes metastasis becomes the key determinant for tumor stage, prognosis, and treatment. Historically, mediastinoscopy has been the gold standard for evaluating mediastinal nodes. However, with advances in current noninvasive imaging there has been increasing use of noninvasive imaging to evaluate the mediastinum.

Chest radiography

As a single imagine modality, chest radiography is rarely solely used for staging because it cannot accurately detect lymph node metastases, chest wall invasion, or invasion of mediastinal structures, although it can detect pleural effusions and multiple pulmonary masses. Despite its limited use, chest radiographs are readily available, inexpensive, and provide a lot of information with a minimal effective radiation dose.

Computed tomography

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans are performed in nearly everyone with a suspected NSCLC. Many of the older studies evaluating the use of CT scans are based on older technology limited to 5- to 10-mm cuts. Newer multislice scanners are able to obtain cuts with a slice thickness of 1.25 to 2.5 mm. The CT scan should include all of the thoracic structures starting from the neck, and continuing down through the abdomen to include the liver and adrenals. Intravenous contrast should be used to help distinguish vascular structures from mediastinal structures and lesions. Intravenous contrast also facilitates assessment of potential vascular involvement of the superior vena cava, pulmonary veins, pulmonary arteries, systemic mediastinal arterial structures, and cardiac structures.

CT scans are safe, quick, painless, and produce a great deal of information. It has become the initial imaging procedure for the staging of bronchiogenic carcinoma. Of particular importance is the presence or absence of mediastinal nodal (N2 and N3) disease. Lymph node enlargement (measured in the short axis) presumes lymph node metastasis in the context of a newly diagnosed or suspected NSCLC. The predictive accuracy depends on the size of the lymph nodes chosen as the upper limit of normal. CT images cannot distinguish malignant from inflammatory nodal tissue, so reactive lymph adenopathy may be mistaken for metastatic disease.

Normal mediastinal lymph nodes are usually less than 10 mm, although normal subcarinal lymph nodes can reach a diameter of 13 to 15 mm ( Box 1 ). Any lymph nodes exceeding these sizes are significantly more likely to contain malignant disease. Normal lymph nodes are rarely seen in the retrocrural region, para-aortic region, or pericardial fat. Lymph nodes exceeding 8 mm in these regions should be considered suspicious.

| 1. | Highest mediastinal |

| 2. | Upper paratracheal |

| 3. | Prevascular and retrotracheal |

| 4. | Lower paratracheal (including azygos nodes) N2 = single digit, ipsilateral N3 = single digit, contralateral or supraclavicular |

| 5. | Subaortic (A-P window) |

| 6. | Para-aortic (ascending aortic or phrenic) |

| 7. | Subcarinal |

| 8. | Paraesophageal (below carina) |

| 9. | Pulmonary ligament |

| 10. | Hilar |

| 11. | Interlobar |

| 12. | Interlobar |

| 13. | Segmental |

| 14. | Subsegmental |

In a meta-analysis of 35 studies, and 5111 patients by Silvestri and coworkers, CT scans were used to evaluate for mediastinal nodal disease. In this population disease prevalence was found to be 28. CT predicted mediastinal lymph node metastasis with a sensitivity and specificity of 51 and 86, respectively.

Mediastinal lymph nodes are graded as N0, N1, N2, or N3 ( Fig. 1 ). The assignment should be considered tentative, because the use of lymph node enlargement as a surrogate for malignant disease is imperfect. Metastatic disease can exist in normal-size lymph nodes, whereas hyperplastic, benign lymph nodes can exceed 10 mm.

To address this issue, Arita and colleagues specifically examined lung cancer metastases to normal-sized mediastinal lymph nodes in 90 patients. Using a cut off of 10 mm, 14 patients with negative CT scans were found to have occult N2 or N3 metastasis after thoracotomy resulting in a 16% false-negative rate.

Efforts have been made to identify low-risk tumors where a negative CT scan would eliminate the need for mediastinoscopy. Dillemans and colleagues reported a selective mediastinoscopy strategy, proceeding straight to thoracotomy without mediastinoscopy for T1 peripheral tumors without enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes on preoperative CT. This strategy resulted in a 16% incidence of positive nodes discovered only at the time of thoracotomy. For identifying N2 disease, chest CT scans had a sensitivity and specificity of 69% and 71%, respectively. When both a CT scan and a subsequent mediastinoscopy were used the accuracy improved (89% vs 71%).

Thus, because of the low sensitivity and poor negative predictive value of CT scan tissue sampling is required to confirm the presence or absence of regional lymph node involvement in the mediastinum.

Computed tomography

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans are performed in nearly everyone with a suspected NSCLC. Many of the older studies evaluating the use of CT scans are based on older technology limited to 5- to 10-mm cuts. Newer multislice scanners are able to obtain cuts with a slice thickness of 1.25 to 2.5 mm. The CT scan should include all of the thoracic structures starting from the neck, and continuing down through the abdomen to include the liver and adrenals. Intravenous contrast should be used to help distinguish vascular structures from mediastinal structures and lesions. Intravenous contrast also facilitates assessment of potential vascular involvement of the superior vena cava, pulmonary veins, pulmonary arteries, systemic mediastinal arterial structures, and cardiac structures.

CT scans are safe, quick, painless, and produce a great deal of information. It has become the initial imaging procedure for the staging of bronchiogenic carcinoma. Of particular importance is the presence or absence of mediastinal nodal (N2 and N3) disease. Lymph node enlargement (measured in the short axis) presumes lymph node metastasis in the context of a newly diagnosed or suspected NSCLC. The predictive accuracy depends on the size of the lymph nodes chosen as the upper limit of normal. CT images cannot distinguish malignant from inflammatory nodal tissue, so reactive lymph adenopathy may be mistaken for metastatic disease.

Normal mediastinal lymph nodes are usually less than 10 mm, although normal subcarinal lymph nodes can reach a diameter of 13 to 15 mm ( Box 1 ). Any lymph nodes exceeding these sizes are significantly more likely to contain malignant disease. Normal lymph nodes are rarely seen in the retrocrural region, para-aortic region, or pericardial fat. Lymph nodes exceeding 8 mm in these regions should be considered suspicious.

| 1. | Highest mediastinal |

| 2. | Upper paratracheal |

| 3. | Prevascular and retrotracheal |

| 4. | Lower paratracheal (including azygos nodes) N2 = single digit, ipsilateral N3 = single digit, contralateral or supraclavicular |

| 5. | Subaortic (A-P window) |

| 6. | Para-aortic (ascending aortic or phrenic) |

| 7. | Subcarinal |

| 8. | Paraesophageal (below carina) |

| 9. | Pulmonary ligament |

| 10. | Hilar |

| 11. | Interlobar |

| 12. | Interlobar |

| 13. | Segmental |

| 14. | Subsegmental |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree