Fig. 41.1

Serum calcitonin (Ct) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) during the years of follow-up of the patient: a more significant increase of both markers was observed just before the starting point of the TKI therapies just anticipating the imaging evidence of a significant increase of the size of the metastatic lesions

From January 2007 to April 2010, no clinical, biochemical, and radiological findings of progression of MTC were observed; the diarrhea was under control with loperamide, and our patient had an acceptable quality of life. In October 2010, we found a slight increase of serum Ct and CEA with a relatively short and concerning doubling time (i.e., 1.4 year); the total body (TB) CT scan showed the presence of at least 4 mediastinal suspicious but subcentimeter lymph nodes and confirmed the stable lung microlesions. At this time, we decided upon a wait-and-see strategy, because of no evidence of significant radiological progression of the disease. The patient’s clinical status remained stable until November 2013, when a rising serum Ct value was observed, with a doubling time <0.5 years (i.e., 3797 pg/ml vs. 1180 pg/ml of March 2013); similarly, an increase in CEA was found with a doubling time of 1.4 years (65 ng/ml vs. 47 ng/ml of March 2013). The neck US revealed the presence of a new 11 mm lymph node in the right paratracheal area. The CT scan showed a new metastatic lymph node in the right hilum measuring 24 mm and a 116 % increase of the largest diameter of a mediastinal lymph node (from 12 mm to 26 mm in 6 months). In this period, the diarrhea was no longer well controlled despite regular therapy with loperamide.

Because of clear progression of the disease, in July 2014, we decided to initiate therapy with the TKI vandetanib (which became available for prescription in our country in June 2014 with the commercial name Caprelsa) with a starting dose of 300 mg daily. The severity of diarrhea immediately improved, but 6 weeks after the initiation of vandetanib, the patient developed a severe and extensive papular rash on the face, hands, and head (Fig. 41.2). This adverse event (AE) was considered to be grade 3 (i.e., very severe) and required the suspension of the TKI therapy until its complete resolution. In the meantime, topical and oral glucocorticoids, antihistamines, and antibiotics to prevent microbial superinfection were administered. After the resolution of this AE, we restarted vandetanib but at a reduced daily dose (100 mg daily).

Fig. 41.2

The patient developed a severe erythroderma a few weeks after the start of the vandetanib therapy, mainly involving the sunlight-exposed areas of the body

At the last evaluation on November 2014 (after 3 months of vandetanib therapy at 100 mg daily), the patient presented for follow-up in good clinical condition, without diarrhea or the need for antidiarrheal medication. His ECG showed a normal QTc interval, and serum electrolytes were in the normal range as were thyroid function tests after a levothyroxine dose adjustment performed in September 2014 because of an elevated serum TSH. TB CT scan showed a slight reduction of the right paratracheal lymph node (10 mm vs. 11 mm) and a significant reduction of the lesions in the mediastinum (20 mm vs. 26 mm) and in the hilum (10 mm vs. 24 mm) (Fig. 41.3); the microlesions in the lung remained stable. He will continue vandetanib until there is no longer evidence of clinical benefit or if there is the development of another severe AE.

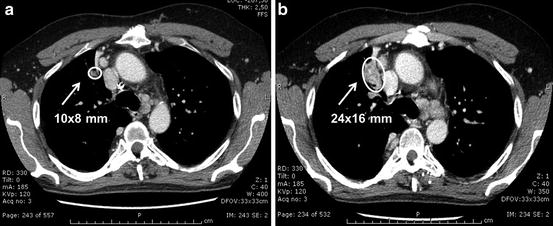

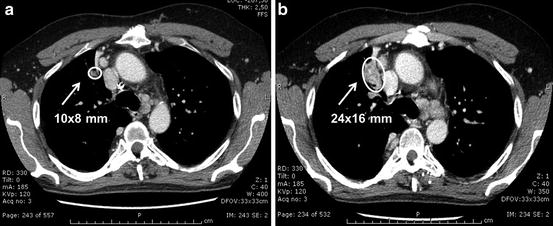

Fig. 41.3

CT scan of the lung performed 6 months after the vandetanib treatment (Panel a) showed a significant reduction of the metastatic lesions and in particular of the lymph node of the hilum with respect to the CT scan performed before starting vandetanib (10 mm vs. 24 mm: −58 %) (Panel b)

Diagnosis/Assessment

This case offers the opportunity to discuss some issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of advanced and metastatic disease in MTC patients. It is known that MTC can be sporadic (80 %) or familial (20 %), and the latter condition can be isolated (i.e., familial medullary thyroid cancer, FMTC) or associated with other endocrine neoplasia (i.e., multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, MEN 2) [1]. In both cases, sporadic or familial, the pathogenesis of MTC is associated with the presence of a somatic or germline RET oncogene mutation, respectively [2]. This case had an apparently sporadic MTC without any familial history of MTC or any other associated endocrine neoplasia. However, RET mutational screening revealed a germline RET Ser891Ala mutation consistent with familial MTC. This finding is not unexpected since 6–7 % of apparently sporadic MTCs are positive for a RET germline mutation when the genetic screening is performed [3]. The case illustrates the importance of performing RET genetic screening in all MTC cases, regardless of the clinical presentation. The finding of a germline RET mutation does not have any impact on the clinical management of the MTC of index case, but at variance, it is of great relevance for the first-degree relatives, who gain the knowledge of either having or not having the inherited RET mutation. The RET-positive cases (i.e., gene carriers) require further investigation because they are at high risk of developing the MEN 2 syndrome. A prophylactic thyroidectomy potentially allows a definitive cure of these individuals, who probably would have had the diagnosis made too late if the RET screening was not performed. The timing of thyroidectomy and the modalities of follow-up should be personalized according to the specific RET mutation and the levels of serum Ct [4, 5].

Management

As previously stated, the finding of a germline RET mutation does not change the therapeutic strategy of MTC for this patient, who has been managed according to the biochemical and imaging results obtained during his follow-up. The disease was not cured by the first surgery, but this is consistent with the evidence that when MTC is already extrathyroidal and associated to neck lymph node metastases, the possibility of a definitive cure is rare [6]. This is the rationale for making an early diagnosis of MTC, either by measuring serum Ct in patients with thyroid nodules [7] or performing RET screening in hereditary forms [8]. In 2006, the patient was enrolled in a clinical trial with motesanib because of the development of diarrhea, which is a common symptom in advanced MTC with very high levels of serum Ct. The clinical trial was of interest because motesanib was the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) employed in thyroid cancer and in particular in MTC [9]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are multitargeted therapies, which mainly block the activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (mainly type 2) but also interfere with the function of other tyrosine kinase receptors including, in some cases, the one coded by the RET oncogene. The patient had a clinical benefit from treatment, including full control of diarrhea, but unfortunately, a severe side effect such as the hydrops of the gallbladder required the discontinuation of the drug.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree