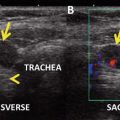

Fig. 1.1

Longitudinal (a) and transverse (b) grayscale sonographic appearance of a 9 × 13 × 18 mm solid, isoechoic, noncalcified nodule with regular margins

Assessment and Literature Review

The risk of malignancy for a nodule with a cytologic diagnosis of “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” is approximately 25 % [1, 2]. The standard of care has been diagnostic lobectomy followed by completion thyroidectomy if the nodule is malignant on histopathology. However, most (~75 %) patients who undergo surgery have a benign nodule.

Once a clinician is confronted with a patient with a follicular cytologic diagnosis, the relevant clinical question is that patient’s risk of cancer. The application of molecular diagnostic tools to nodules with follicular neoplasm cytology is predicated upon the assumption that results can further refine malignancy risk in these patients where cytology is not definitive. If molecular testing techniques were 100 % sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of all thyroid cancer histologies, this technology could replace cytologic analysis. Perhaps future testing strategies will achieve this goal, but current commercially available molecular diagnostics do not. Therefore, to interpret results of these molecular tests for an individual patient, the clinician must understand the reported negative and positive predictive values and their derivation from recently published studies.

A high negative predictive value (NPV) signifies that the cancer risk is very low when the test result is negative, e.g., NPV of 97 % is associated with a cancer risk of only 3 %. On the other hand, a high positive predictive value (PPV) indicates that the likelihood of malignancy is high when the test is positive, e.g., PPV of 90 % means that cancer is present in 90 % of patients with this result. The point estimates for NPV and PPV for a given test vary based upon the prevalence of disease (thyroid cancer) in the tested population. For example, when the cancer risk is low, e.g., 10 %, even a test with a sensitivity of 60 % will be associated with an NPV of over 95 %. Here, because there are so few cancers in the population, the absolute number of cases where the test fails to accurately diagnose cancer is very low, and this does not significantly decrease the NPV. But, as the cancer rate rises, this same test with 60 % sensitivity will miss more diagnoses leading to a higher false-negative rate and lowering the NPV. On the other hand, the PPV rises as the population disease risk increases because false-positive results decrease when there are fewer patients without thyroid cancer.

Therefore, for a given patient, the application and interpretation of results from currently available molecular diagnostics for prediction of malignancy or benignity are predicated upon that patient’s baseline malignancy risk after cytologic diagnosis, i.e., the “pretest probability.” Although overall the risk of malignancy associated with a “follicular neoplasm” cytologic result is approximately 25 % [1, 2], certain factors may modify this estimate and could potentially alter the interpretation of subsequent molecular diagnostic results. Prior to the discussion of the recent publications about the application of molecular testing, we will review the literature on patient demographics and nodule sonographic features that may alter malignancy risk associated with a nodule with a “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” diagnosis, henceforth referred to as an FN nodule.

Part I: Risk of Malignancy

Limitations of Cytologic and Histologic Interpretation

The diagnosis of “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” (FN) is rendered in approximately 10–15 % of FNAs performed. A 2012 meta-analysis including eight studies showed center-specific rates ranging from 1.2 to 25.3 % [1]. Of the three indeterminate cytology classifications defined by the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology [3], follicular neoplasm is the most reliably reproducible. Interobserver diagnostic agreement is considered fair (kappa 0.5), based on Fleiss’ criteria for interpreting kappa values [4].

The standard of care for patients with such indeterminate cytology has been diagnostic lobectomy followed by completion thyroidectomy if histology is malignant. In this meta-analysis, 70 % of patients with FN nodules underwent surgery, similar to the rate of resection for cytology suspicious or indicative of malignancy [1]. Approximately 25 % of FN nodules are malignant on histology [1, 2], with center-specific rates ranging from 14 to 49 % [2]. Of these cancers, 16–36 % are follicular carcinomas, but most (55–84 %) are papillary thyroid cancers, with follicular variant as the most common subtype [5–8]. Although clinicians consider pathology the diagnostic “gold standard,” even expert pathologists may disagree about the distinction between benign and malignant nodules on histology in up to 10 % of cases [2, 9].

Demographic and Sonographic Features Predictive of Malignancy

Once a nodule has a cytologic diagnosis of “suspicious for follicular neoplasm,” some studies have reported that certain clinical features, including male gender, age, and the presence of a solitary nodule, are predictive of malignancy, but these findings have not been consistent [10–18] (Table 1.1). Large nodule size, in contrast, may be a reliable predictor of follicular thyroid carcinoma [11, 12]. Nodule size greater than or equal to 2.8 cm has been associated with an 11-fold increased risk of follicular thyroid carcinoma, but not with an increased risk of papillary thyroid carcinoma, which is typically smaller [11]. For example, in one study [12], nodule size only achieved statistical significance as a predictor of malignancy in FN nodules after papillary carcinoma was excluded from analysis. Consistent with these findings, nodule size was not predictive in three studies when the malignant histologic diagnoses were predominately papillary [13, 16, 17]. Only a single study with predominately follicular cancers failed to show nodule size as a significant predictor [14].

Table 1.1

Clinical features predictive of malignancy in a nodule with a cytologic diagnosis of suspicious for follicular neoplasm

Clinical feature | Predictive | Not predictive |

|---|---|---|

Male gender | Tuttle [10] | Lubitz [12] |

Lee [11]—FTC only | Glucelik [13] | |

Choi [14] | ||

Rago [16] | ||

Raber [17] | ||

McHenry [18] | ||

Younger age | Schlinkert [15] | Tuttle [10] |

Lee [11] | ||

Lubitz [12] | ||

Glucelik [13] | ||

Choi [14] | ||

Rago [16] | ||

Raber [17] | ||

McHenry [18] | ||

Nodule size | Lee [11] ≥2.8 cm—FTC only | Glucelik [13] |

Lubitz [12] ≥4.0 cm—when PTC excluded from analysis | Choi [14] | |

Rago [16] | ||

Raber [17] | ||

Solitary nodule | Raber [17] | Lubitz [12] |

Glucelik [13] | ||

Rago [16] |

For the initial evaluation of a thyroid nodule, certain sonographic features are consistently predictive of malignancy and can be used to determine the size threshold for FNA. These include hypoechoic echogenicity, solid composition, the presence of microcalcifications, irregular borders, and “taller than wide” shape [19]. However, once a “suspicious for follicular neoplasm” cytology is diagnosed, the reliability of ultrasound features to predict malignancy is less robust [11, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20] (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2

Grayscale and Doppler sonographic features predictive of malignancy in a nodule with a cytologic diagnosis of suspicious for follicular neoplasm

Sonographic feature | Predictive | Not predictive |

|---|---|---|

Hypoechoic echogenicity | Glucelik [13] | Lee [11]a |

Raber [17] | Choi [14] | |

Rago [16] | ||

Solid composition | Glucelik [13] | Lee [11] |

Choi [14] | ||

Microcalcifications | Glucelik [13] | |

Rago [16] | ||

Internal blood flow | Choi [14] | |

De Nicola [20] |

The presence of microcalcifications in an FN nodule has been associated with an increased but variable (32–84 %) malignancy risk [13, 16]. This variability may be explained by higher proportions of classic versus follicular variant papillary carcinomas. Microcalcifications are thought to correspond to psammoma bodies on histology, and these are commonly found in classic variant papillary thyroid carcinomas, but not in follicular variant papillary carcinomas or follicular carcinomas [21, 22].

Hypoechogenicity in FN nodules correlated with a 33–43 % risk of malignancy in two studies [13, 17], but it was not predictive of malignancy in three other studies [11, 14, 16]. When the histologic diagnoses included a higher proportion of classic variant papillary thyroid carcinomas, which are typically hypoechoic [23], this association was observed. Conversely, the characteristic grayscale sonographic appearance of both follicular carcinoma and follicular variant papillary carcinoma is an iso- or hyperechoic nodule [23, 24]. In one study with a higher percentage of follicular cancer in FN nodules, isoechogenicity was predictive of follicular carcinoma but not papillary carcinoma [11].

Nodule composition (solid versus cystic) may also relate to histopathology because papillary cancers are more likely to be solid than follicular cancers [24]. Solid nodule composition was associated with a 38 % risk of malignancy in the study with the highest proportion of papillary cancers in FN nodules [13].

In addition to the grayscale sonographic features typically considered hallmarks of malignancy, the presence of internal blood flow, as assessed by Doppler examination, may be a predictor in nodules with a cytologic diagnosis of “suspicious for follicular neoplasm.” Internal blood flow was associated with a 28–50 % risk of malignancy in two studies [14, 20]. This finding is likely due to the high proportion of follicular cancers diagnosed in these studies. Follicular carcinomas have been shown to exhibit penetrating, intranodular blood flow, while follicular adenomas frequently exhibit peripheral blood flow [25, 26], although no difference was found in a recent study from the Mayo Clinic [27].

In summary, grayscale and Doppler sonographic features may further refine the malignancy risk of an FN nodule. However, the application of these findings to one’s clinical practice depends upon the institution-specific proportion of follicular versus papillary carcinomas diagnosed histologically in nodules with a cytologic diagnosis of “suspicious for follicular neoplasm.”

Part II: Molecular Evaluation

Molecular Genetics in Thyroid Cancer

Gene point mutations and rearrangements are identified in 61–75 % of thyroid cancers [5, 28, 29]. Mutations are generally mutually exclusive. The MAPK and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways, which regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, are the main pathways involved in tumor genesis. Activating mutations in the MAPK pathway are common in papillary carcinomas, whereas activating mutations in the PI3K-AKT pathway are more common in follicular carcinomas [30]. RAS point mutations and PAX8/PPARγ rearrangements are the most common mutations identified in follicular carcinomas and follicular variant papillary carcinomas, the cancers most frequently diagnosed in nodules which are cytologically “follicular neoplasm” [5, 29].

NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS genes encode intracellular G proteins involved in both pathways. The most common RAS mutations occur in NRAS codon 61 and HRAS codon 61. RAS mutations occur in 40–50 % of follicular thyroid cancers and 10–20 % of papillary cancers, most of which are follicular variant. RAS mutations are also identified in 20–40 % of follicular adenomas [5, 30]. The PAX8/PPARγ rearrangement leads to the fusion of the PAX8 gene coding for a thyroid-specific transcription factor and the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor. The mechanism by which this rearrangement promotes carcinogenesis is not entirely clear. It occurs in 30–35 % of follicular cancers as well as up to 13 % of benign follicular adenomas. In addition, it is found in 1–5 % of papillary cancers but only in the follicular variant [30]. The occurrence of RAS and PAX8/PPARγ mutations in both benign and malignant nodules has led some to suggest that adenomas harboring these mutations are premalignant, but this is unproved [5, 30, 31].

In contrast, BRAF point mutations , which are the most common mutations identified in papillary carcinomas, are only found in malignant nodules [5, 29]. BRAF is an intracellular serine-threonine kinase involved in the MAPK pathway. The most common mutation is V600E, accounting for 98–99 % of all BRAF mutations. It is found in 40–45 % of classic and tall cell variant papillary thyroid carcinomas. It is rarely found in follicular variant papillary carcinomas. K601E is the most common BRAF mutation in follicular variant papillary carcinomas [30].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree