Fig. 12.1

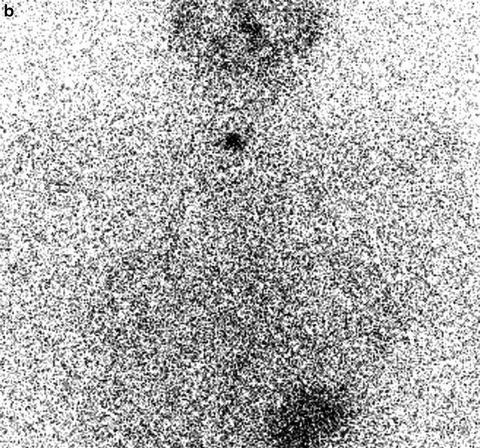

A 17-year-old female with a locally metastatic PTC presented for further evaluation at a tertiary cancer center after having already had two surgeries. Cervical ultrasonography revealed a suspicious, 1.3 cm right level IV lymph node (a, arrow), which was proven to be PTC after fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Despite the presence of residual lymph node disease, there was no indication of iodine-avid lateral neck metastases on a diagnostic 123I thyroid scan (b). Preoperative contrast-enhanced CT also identified a suspicious lymph node in the right tracheoesophageal groove (c, arrow), which was resected and proven to be PTC. Subsequent to her third surgery, the patient had no evidence of residual PTC, and she remains disease-free greater than 4 years after her last surgery.

Assessment and Literature Review

Thyroid cancer is rare in the pediatric population, but the incidence appears to be increasing, especially in adolescents. PTC is the most common type, accounting for 90 % or more of childhood thyroid cancers, followed by follicular and, rarely, medullary thyroid carcinoma. PTC is frequently multifocal and bilateral, and in children, regional lymph node metastases occur in >80 % of cases at diagnosis [1–7]. Patients with a significant volume of cervical disease are at the highest risk of hematogenous metastases to the lungs [3, 4], which occur in up to 25 % of pediatric cases in some series [5, 8–10]. Despite more extensive disease at clinical presentation, pediatric PTC is biologically distinct from PTC diagnosed in older adults, and children with PTC have an extremely low disease-specific mortality (2 % or less decades after diagnosis) [9, 11]. This excellent prognosis, coupled with unique concerns regarding the possible long-term sequelae related to overzealous treatment during childhood, makes the management of pediatric PTC challenging. It is only recently that formal guidelines for the management of pediatric PTC have been developed by the American Thyroid Association (ATA) [12].

Children with PTC typically present with a palpable thyroid nodule and/or overt cervical lymphadenopathy [1, 2], which is not uncommonly treated with an antibiotic before the diagnosis of PTC is recognized. The initial workup of suspected PTC should include a comprehensive cervical and soft tissue neck US by an experienced ultrasonographer, given the high rate of lymph node metastases. US-guided FNAB in children is a sensitive and specific tool for the diagnosis and management of PTC, and it is recommended in all children to confirm the diagnosis and properly stage the extent of cervical disease. FNAB of suspicious lymph nodes is also essential for planning the appropriate initial surgical approach, which is the mainstay of therapy in pediatric PTC.

Contemporary guidelines recommend that children with PTC be cared for at centers where there is multidisciplinary expertise in the management of pediatric thyroid cancer [12], and it is always preferred that surgery be performed by a high-volume thyroid surgeon, defined in previous studies as a surgeon who performs 30 or more cervical endocrine procedures annually [12, 13]. Most pediatric patients with PTC will require a total thyroidectomy (TT) with or without a compartment-oriented neck dissection. The type of surgery planned is based on the results of preoperative comprehensive neck ultrasonography and FNAB. Additionally, cross-sectional imaging, using either a contrast-enhanced CT of the neck or MRI, is recommended for those with fixed thyroid masses, vocal cord paralysis, or bulky lymphadenopathy [12, 14]. Although the use of iodinated CT contrast may delay postoperative evaluation and treatment with RAI, it is considered the best diagnostic study in which to inform the surgeon about the extent of cervical disease and its anatomic relationship with critical aerodigestive structures.

Current data suggest that the single most important factor for improving long-term disease-free survival is the extent of the initial surgery, with more comprehensive surgery decreasing or eliminating the need for additional surgery and decreasing the risk of recurrence [4, 7, 9–11, 15, 16]. However, previous studies are confounded by the routine use of RAI, and so further studies are required. Current ATA guidelines recommend a CND in children who have gross extrathyroidal invasion and/or locoregional metastasis identified either pre- or intraoperatively [12]. Lateral neck dissection is recommended in those with FNAB-proven lateral neck disease.

The role of prophylactic CND in pediatric PTC without imaging evidence of lymph node metastases is very controversial. Due to the very high prevalence of cervical metastasis in children, prophylactic CND may be selectively considered based upon tumor size and focality. For patients with unifocal PTC, especially tumors >1 cm [17], an ipsilateral CND, with pursuit of contralateral CND only if intraoperative findings suggest central compartment disease, may help to balance the risks and benefits. In all cases, the plan for CND should be driven by the experience of the surgeon. Preservation of parathyroid and voice function is paramount, even if all central neck disease is not removed.

The inaugural ATA guidelines introduced a new risk categorization (ATA pediatric low, intermediate, and high risk) that helps to identify patients at risk of persistent cervical disease and to determine which patients should undergo more intensive postoperative staging [12]. Children with incidental, microscopic central lymph node disease are considered low risk, with recommendations to monitor thyroglobulin (Tg) levels and neck US after the initial surgery. Children with more significant central or lateral neck disease are considered ATA pediatric intermediate (clinical N1a or microscopic N1b disease) or high risk (clinical N1b disease), and postoperative staging with a diagnostic RAI scan and a TSH-stimulated Tg is recommended to identify persistent locoregional or distantly metastatic disease [12, 14]. Children who are found or suspected to have iodine-avid nodal disease may benefit from 131I therapy if the disease is not amenable to further surgery, as determined by consultation with a thyroid cancer surgeon. Children who have no scintigraphic or Tg evidence of residual cervical disease or distant metastases may not benefit from routine adjuvant 131I therapy [12, 14], but further research is needed. Nevertheless, decisions regarding 131I therapy in pediatric PTC should weigh the long-term risks of RAI (primarily second malignancies [11]) against the potential benefits of therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree