(1)

Daytona Beach Shores, FL, USA

Beneath it [the cancer cell] there must exist some more intimate element which science would need in order to define the nature of cancer

– Alfred Velpeau (1795–1867)

Because cancer arises from the interaction of multiple factors not yet fully understood, this Chapter will describe the status of our still incomplete knowledge.

3.1 The Genetic Bases of Cancer

3.1.1 First the Basics

In the popular mind, cancer conjures up notions of pain, despair, and finality. However, cancer is not a single disease but an assortment of more than 300 very diverse malignancies that can arise from all tissues and organs (broadly divided into leukemias arising from blood cells and solid tumors emerging from solid organs), become clinically manifest at various stages of development, and exhibit a wide spectrum of biological and progression patterns, each impacting the bearer’s survival. Additionally, more than one type of cancer can originate from an organ or tissue, as dramatically exemplified by the over 120 types of brain and central nervous system tumors both benign and malignant and the 70 types of lymphomas according to the 2008 World Health Organization’s (WHO) classification [121]. From a clinical standpoint, cancers can exhibit slow growth patterns compatible with long and symptom-free survival, such as indolent lymphomas and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [122], or quickly progress to death in only a few months, as exemplified by pancreatic cancer [123]. Likewise, some cancers spread distally from the site of origin, including colon, prostate, and lung cancers that often metastasize to liver, bone, and brain, respectively, whereas others tend to invade locally as is the case of head and neck cancers. Yet, despite their heterogeneous origin, distinct clinical features, and vastly different clinical course and outcome, the underlying genetic processes identified to date leading to their development, growth, and dissemination are broadly similar, mainly mutations occurring in proto-oncogenes,1 tumor suppressor genes2 or microRNA genes.3

The master blueprint that determines the structure and function of all organisms, including man, is called the genome. Each of the approximately 30 trillion cells that make a human being contains a copy of the entire genome and its approximately 20,000–25,000 genes, neatly packaged in 46 microscopic units called chromosomes found bundled in the cell nucleus. Genes are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences that contain the code for cells to produce proteins, which are the signals that control the structure and function of each cell, of each organ, and ultimately of the entire organism. These cell-produced, cell-targeted protein signals are at the center of the interdependent relationship that characterizes both the harmonious function of normal cells and the aberrant behavior of cancer cells. Thus, the genome can be thought of as the book of life where chromosomes are chapters and genes are the carefully crafted sentences made of precise words spelled with nucleotide bases (letters), all sequentially arranged on the DNA molecule. During the process of cell division and of human reproduction the entire genome must be duplicated and passed from cell to cell and from parent to offspring, respectively. While this process is prodigiously accurate, spelling errors do occur. DNA repair genes correct minor, non-lethal alterations. Major errors activate gatekeeper genes that block cell replication and force the cell to commit suicide (apoptosis). The role of DNA repair and gatekeeper genes is to ensure genomic integrity as cells advance through their replication cycle (cell cycle). However, occasional non-lethal alterations escape detection, repair, or blockade and are transmitted from a replicating cell to its daughter cells, giving rise to a genetically abnormal cell line. Transmitted alterations of DNA sequences outside of genes, called polymorphism, are neither beneficial nor harmful to the cell or the host. Conversely, transmitted alterations within gene sequences, called mutations, are responsible for approximately 4,000 human diseases, including cancer. When mutations affect a sex cell or gamete (egg or sperm), they can be transmitted to future generations, resulting in familial predisposition to diseases such as hemophilia, and to some cancers such as retinoblastoma. At present, the genetic fingerprints of most cancers are not known mainly because insensitive detection techniques of the pre-genomic era uncovered mostly structural chromosomal abnormalities visible by light microscopy that are seldom disease-specific. While diagnostically and prognostically valuable in the clinical setting, such gross abnormalities seldom provide insight into the genetic defects responsible for the development, growth, and dissemination of cancer.

Recognizing that the genome occupied a central role in health and disease, in 1987, the “Health and Environmental Research Advisory Committee (HERAC), recommends a 15-year, multidisciplinary, scientific, and technological undertaking to map and sequence the human genome. Department of Energy designates multidisciplinary human genome centers” [124]. A year later the NIH received congressional authority and funding to coordinate and support genomics activities in cooperation with other federal agencies, academia, and international groups. An independent NIH institute, named The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), was created to that effect. Francis Collins M.D., who had participated in the discovery of several elusive genes including those linked to cystic fibrosis, neurofibromatosis, and Huntington’s disease, was chosen as its head. The overall project goal was to identify the position and sequence of the three-billion nucleotide bases that make up the human genome. However, because the book of life is written as a continuous string of sequential letters without separation or punctuation between words, sentences or paragraphs, deciphering the position and sequence of the nucleotide bases would still be unreadable and uninterpretable. Thus, another major goal was to identify all human genes (the words and sentences made up of strings of letters) and determine their location. The project formally began on October 1, 1990, cosponsored by the DOE and the NIH, as a $3 billion, 15-year effort. The first 5-year plan, intended to guide research between 1990 and 1995, was revised in 1993 due to unexpected progress. The second, third and final 5-year plans outlined goals through 1998 and 2003, respectively. Some 18 countries participated in the worldwide effort, with significant contributions from research centers in the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Japan. However, in direct competition with this multinational group of government and academic research centers arose Celera Genomics, a biotechnology company established in May 1998 by J. Craig Venter, Ph.D., founder of the Institute for Genomic Research at the NIH, with venture capital funding from Perkin-Elmer Corp. Using a faster DNA sequencing strategy known as the whole-genome shotgun sequencing method, and highly automated sequencing machines that require human attention only 15 min per day despite running continuously, Celera (swift in Latin) was able to publish, in February 2001, a working draft of the human genome sequence [125]. The same month, the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium published its own draft, 10 years in the making and at ten times Celera’s cost [126]. These publications marked the end of a race punctuated by “acrimonious feud between the public and private teams” and their American leaders [127]. Although heralded as the crown jewel of twentieth century biology when it was first proposed, the Human Genome Project (HGP) was greeted by many scientists and researchers as, “Absurd, dangerous, and impossible…who noted that the technology did not exist to sequence a bacterium, much less a human…” [128]. The human genome sequence was completed in April 2003. However, many years will pass before this information is translated into tangible benefits in the clinical arena, for it will require uncovering the genetic bases of disease and designing targeted agents to prevent, reverse, or control the defective genes, or to modulate or block their encoded protein products, an endeavor far more complex than anticipated. In the meantime, government- and industry-sponsored initiatives have made substantial progress, particularly speeding DNA sequencing, and gene identification and mapping. For example, while it took Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui’s team 9 years to discover the cystic fibrosis gene in 1989 [129], the Parkinson’s disease gene was mapped in only 9 days by Dr. Robert Nussbaum’s team 9 years later [130]. Likewise, the cancer gene-discovery process also proceeded at a rapid pace as demonstrated by the fact that over just a few years,

As our knowledge in cancer genetics continues to accrue and deepen, the post-genomic period will be remembered as the era when the genetic defects that render normal cells malignant were uncovered and when that knowledge was exploited for designing means to prevent, control, and reverse the genetic defects responsible for the development, growth, and dissemination of cancer.

…more than 1,000 somatic mutations found in 274 megabases (Mb) of DNA corresponding to the coding exons of 518 protein kinase genes in 210 diverse human cancers…[of which] there was evidence for ‘driver’ mutations contributing to the development of the cancers studied in approximately 120 genes [131].

Further details on the basic aspects on the genetics and epigenetics of cancer follow. However, Readers not especially interested in such details can bypass this segment and advance to the section How does cancer arise?, starting on page 54.

3.1.2 More Details

3.1.2.1 DNA

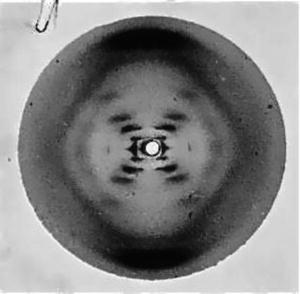

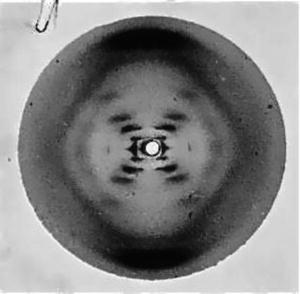

On March 7th, 1953, Francis Harry Crick, a 35-year old graduate student at the Cavendish laboratory of the University of Cambridge, England, walked into the Eagle pub and declared, “we have found the secret of life”. He was referring to his and James Dewey Watson’s discovery of the structure of DNA that explained transmission of genetic information from cell to cell and from parent to offspring, and helped understand how genetic mutations are produced. Theirs was a brilliant interpretation of another investigator’s published and, reportedly, still unpublished research data. Crick’s career had evolved from physics to chemistry and biology. On the other hand, the 23-year old Watson had received a B.S degree from the University of Chicago and a Ph.D. degree in zoology from Indiana University. However, as a research fellow at the Cavendish laboratory, he abandoned his chosen field for the pursuit of glory, as he recounts in his memoirs entitled The double Helix: A personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA, first published in 1968 [132]. In that self-serving account of the momentous discovery, he described his obsession with the DNA molecule and his anticipation that unraveling its structure would bring the Nobel Prize. After attending a 1951 lecture where the gifted Rosalind Franklin presented X-ray crystallography data and her helical concept of the DNA molecule, Watson and Crick built a three-chain DNA molecule model with the backbone on the inside that drew sharp criticism. The head of the Cavendish laboratory, Sir Lawrence Bragg, ordered the unlikely pair to leave DNA to King’s College where Franklin and her rival Maurice Hugh Wilkins were assigned the task. However, when Linus Pauling, the world’s leading structural chemist who would be awarded Nobel Prizes for Chemistry in 1954 and for Peace in 1962, and the odds-on favorite to solve the structure of DNA published a wrong structure for DNA, it became evident to them that someone else might soonlay claim to “the most important of all scientific prizes” [133]. According to a special report published on August 17, 1998 [134], “When Watson came calling in January 1953, Wilkins [who Watson described as ‘a beginner’ in X-ray diffraction work, wanted some professional help and hoped that ‘Rosy’, a trained crystallographer, could speed up his research], revealed he had been quietly copying Franklin’s data. He showed one of her x-ray photos” (Fig. 3.1).

Fig. 3.1

Rosalind Franklin’s crystallography photo #51

Watson was so impressed that he later wrote, “The instant I saw the picture my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race…. the black cross of reflections which dominated the picture could arise only from a helical structure… mere inspection of the X-ray picture gave several of the vital helical parameters” [135]. Watson’s own admission, the fact that neither he nor Crick conducted bench research on DNA, relying instead on other investigators’ data to draw diagrams and construct tri-dimensional models, and the short time between this episode and the publication of their report leads to the inescapable conclusion: Franklin’s work was pivotal in their inferring the correct molecular structure of DNA. Their highly acclaimed and universally accepted model included two helical chains made of sugar-phosphate backbones, as Franklin’s work revealed, held together by complementary pairs of four nitrogen bases interlocked between them. Thus, Watson’s and Crick’s failure to acknowledge Franklin’s crucial role in their formulation of the structure of DNA reported in the April 2, 1953 Nature article [136] where he and Crick disclosed their final model is a most regrettable episode in the annals of great discoveries. To add insult to injury, Watson ridiculed Franklin in his book, stating, “So it was quite easy to imagine her the product of an unsatisfied mother who unduly stressed the desirability of professional careers that could save bright girls from marriages to dull men”. Franklin’s biographer adds “‘Rosy’ was depicted as an aggressive, perhaps belligerent, female subordinate with no respect for her superiors” who “refused to think of herself as an assistant to Wilkins” [137]. Crick, Watson, and Wilkins received the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material” [138]. Watson went on to receive the most honors and recognition, including honorary degrees from 22 universities. Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958, age 37.

From an anatomical standpoint, the genome is contained in tightly coiled strands of DNA organized in chromosomes, which are housed in the cell nucleus. To illustrate the minuscule size of the DNA, suffice it to say that, if unwound, the DNA of a single cell (one million cells fit on the head of a pin) would stretch 5 ft but would be only 50 trillionth of an inch wide. Stretching all the DNA of a human being would reach the sun and back. A human DNA molecule (Fig. 3.2) consists of two strands that wrap around each other like a twisted ladder or a spiral staircase, the so-called double helix, whose sugar and phosphate sides connect to each other by rungs of nitrogen-containing chemicals called bases. Each strand is a linearly repeated sequence called nucleotides, made of one sugar, one phosphate, and one nitrogenous base. There are four different bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). The order of the bases along the sugar-phosphate backbone, called the DNA sequence, is like a barcode that encrypts the genetic instructions necessary for the structural and functional integrity of an organism with its array of unique traits. Weak bonds between bases forming base pairs, of which there are approximately three billion in the human genome, hold the two DNA strands together. Each time a cell divides, its genome is duplicated by DNA replication, a complex process initiated by DNA polymerase, an enzyme that breaks the weak bonds between base pairs, unwinding the helix to allow separation of the two DNA strands. Once separated, each strand directs the synthesis of a complementary DNA strand, including matching bases following strict base pairing: adenine with thymine (A-T pair) and cytosine with guanine (C-G pair). Each daughter cell receives one parental and one new DNA strand, thus minimizing chances of errors (mutations) in gene transfer.

At the functional cellular level, genetic information encoded in nuclear DNA ultimately leads to production of regulatory proteins in the cell cytoplasm. This process requires an intermediary molecule, called ribonucleic acid (RNA). RNA polymerase first unzips a section of nuclear DNA and transcribes (copies), base-by-base, a given sequence of exposed bases, and moves into the cell cytoplasm as messenger RNA (mRNA) where it translates the genetic code (or message) into synthesis of the particular protein encoded in the exposed DNA.

3.1.2.2 Genes

Johann Mendel (Fig. 3.3), born in Hynčice, Moravia (in the Austro-Hungarian Empire) in 1822, entered religious life at the seminary of the Abbey of St. Augustine in Brünn, Moravia’s capital (Brno in today’s Czech Republic) in 1843, taking the name Gregor. He worked on the side as a substitute teacher in a secondary school in Znaim, near Brünn, and tried to upgrade to regular teacher but failed the certification examination. Paradoxically, his lowest mark was in biology. Sponsored by his Abbot, František Cyril Napp (1824–1867), himself an accomplished scholar, Mendel enrolled at the University of Vienna in 1851 where he studied physics, chemistry, mathematics, zoology, and botany. He returned to the abbey in 1853 and became its Abbot in 1867, a demanding responsibility that effectively ended his research career. Although he worked alone, Mendel did not operate in a vacuum, for he drew inspiration from his former teachers Friedrich Franz and Karl Nestler, and his scientific interests and pursuits were supported by a good library at the monastery, by other monks, most notably Aurelius Thaler, a botanical expert who in 1830 had established an experimental garden at the monastery, and by colleagues at the Brünn’s Natural Science Society. Mendel’s now famous paper entitled Versuche über pflanzenhybriden (Experiments with plant hybridization), describing his work on heredity, was presented orally before the Society in February 1865, and published in the Society’s transactions in 1866 [140]. From his modest monastery garden, Mendel had unraveled the secrets of heredity that would earn him the title of father of modern genetics. Yet, his contemporaries failed to understand the importance of Mendel’s work on genetics and his observations fell into oblivion to the point that, for several decades, they were unknown to the public and to scientists, including Charles Darwin [141].

Fig. 3.3

Johann (Gregor) Mendel

Mendel’s success in choosing seemingly rudimentary techniques applied to the study of ordinary garden peas (Pisum sativum) leading to deciphering the secrets of genetics that rest on carefully designed experiments, painstakingly collecting large amounts of data, analyzing results in light of a starting hypothesis, and testing results at each step with a new set of experiments. Choosing garden peas was a carefully considered decision that demonstrated his genius. Indeed, he selected inexpensive and easily available peas of distinct shapes and colors with a short generation time that produce many offspring, enabling him accurately and systematically to sort sequential generations of cross-pollination results. Moreover, in addition to an anatomy designed for self-pollination that prevents cross-pollination, garden peas can be cross-pollinated at will by the experimenter by placing pollen from one plant on the female flowers of another [142]. Mendel selected seven traits or characteristics for study involving various colors and shapes, but first grew the plants for 2 years to ensure a pure line. That is, all offspring produced by 2 years of self-pollination would be identical with regards to each trait under study. His first major observation contradicted the then popular notion known as blending inheritance that assumed that all traits were inherited by the first generation offspring (F1) as a blend or average of the parents’ (P). Thus, crossing a tall plant with a short one, for example, was expected to produce a medium-sized offspring plant. When Mendel pollinated tall or short plants within themselves, offspring plants remained tall or short, as expected. Curiously, when he cross-pollinated plants with green pea pods with plants that had yellow pods, he noticed that all offspring hybrid plants (F1) exhibited green pea pods, as if the yellow pea pod trait had vanished. Yet, when he pollinated two (F1) hybrid plants between themselves, some of their offspring (F2) exhibited yellow pods and others had green pods. This phenomenon reappeared regardless of the trait studied and did so at a constant ratio of approximately 3:1 (Table 3.1). Mendel correctly concluded that hereditary traits are discrete packets or particles that pass unchanged from one generation to the next, although each trait might not be expressed in each generation. He called these packets elemente (elements), and called dominant those elements that appeared in the first offspring (F1) and recessive those that were hidden in the first generation but re-surfaced in the second (F2). He further concluded, also correctly, that paired traits pass from one generation to the next as separate and independent elements, each inherited from one parent. While genetics, particularly human genetics, is more complex, with each trait, physical and otherwise, generally being influenced by more than one gene, Mendel’s concept of elements, which we now call alleles, and his notion that elements are paired and inherited as separate and independent entities from one another in a dominant or recessive fashion remain largely accurate. Yet, despite being pivotal to understanding genetics, Mendel’s momentous work fell into oblivion until 1900 when his article Experiments with plant hybridization was simultaneously re-discovered by Hugo De Vries of the University of Amsterdam, Carl Correns of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin, Erik von Tschermak of the University of Vienna, and British botanist William Bateson. The latter became a fervent advocate of Mendel’s, published a book in defense of his work [144] extending his conclusions to animals and demonstrating that, contrary to Mendel’s findings, certain traits are inherited together by genes located in close proximity on the same chromosome, a phenomenon now known as linkage. Mendel died at the monastery in 1884, where his tombstone reads, “Scientist and biologist in charge of the Augustinian monastery in Old Brno. He discovered the laws of heredity in plants and animals. His knowledge provided a permanent scientific basis for recent progress in genetics.”

Parental trait | F1 | F2 | F2 trait ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

Round × wrinkled seeds | All round | 5474 round – 1850 wrinkled | 2.96:1 |

Yellow × green seeds | All yellow | 6022 yellow – 2001 green | 3.01:1 |

Purple × white petals | All purple | 705 purple – 224 white | 3.15:1 |

Inflated × pinched pods | All inflated | 882 inflated – 299 pinched | 2.95:1 |

Green × yellow pods | All green | 428 green – 152 yellow | 2.82:1 |

Axial × terminal flowers | All axial | 651 axial – 207 terminal | 3.14:1 |

Long × short stems | All long | 787 long – 277 short | 2.84:1 |

Genes are the fundamental physical and functional units of heredity that are passed from parent to offspring. They are made of specific sequences of DNA bases located on a particular chromosome that encode (contain information for) the production of specific proteins that serve as cellular signals. The size of genes varies widely, from approximately 10,000–150,000 base pairs. However, only a fraction (10 %) of the three billion base pairs that constitute the genome represents protein-encoding sequences (exons) of genes, the rest being intercalated sequences (introns) with no known coding function. Additionally, only a small fraction of the approximately 25,000 human genes are expressed in any particular cell. For example, hemoglobin genes are expressed in red blood cell precursors, not in muscle or brain cells. Yet, the very presence of all genes in every cell makes each of them a potential source for cloning virtually any cell lineage, under the right conditions. Gene expression begins with the synthesis of an RNA copy (transcription) of the DNA gene sequence, in the nucleus, followed by its transport mRNA to cytoplasmic ribosomes, where the encoded genetic information is translated into protein synthesis. However, before moving to the cytoplasm, non-functional introns are snipped out and exons are spliced (linked) together, thus giving rise to the proper protein-encoding sequences. Once in the cell cytoplasm, the mRNA serves as a template to translate the encoded information (codons) into a string of individual amino acids that constitute the building blocks of protein synthesis. Codons are sequences of three DNA bases within exons that direct cells to produce a specific amino acid. For example, the sequence ATG codes for the amino acid methionine. There are 64 possible codons encoding 20 amino acids, thus allowing for code redundancy for all but 2 amino acids: methionine (AUG) and tryptophan (UGG). The other 18 amino acids are encoded by 2–6 codons. For example, AAA and AAG encode lysine and UCU, UCC, UCA, UCG, AGU, and AGC encode serine. In addition, there is an initiation codon, usually AUG, that initiates translation of mRNA, and a termination codon, usually UAA, UGA or UAG, that ends it. Thus, when the RNA reads a gene sequence it is prompted where to start and where to end the transcription process. Hence, from a logistic point of view, the genetic code is a series of codons, contained in genes in turn housed in chromosomes located in the cell nucleus, that specify which amino acids will be synthesized and in what order. The 20 amino acids, assembled in a variety of different combinations and lengths, give rise to approximately 100,000 proteins encoded in the human genome that are necessary to maintain the structural and functional integrity of human beings. Errors in DNA or RNA transcription, and in exon splicing, can result in mutations, which in turn can lead to a faulty translation of the gene code, including failure to synthesize the gene-encoded protein or production of an aberrant protein. The outcome of either failure will be a functional disruption of the protein-targeted cell.

3.1.2.3 Chromosomes

Chromosomes are microscopic units that house all genes. Thus, it might be expected that the number of chromosomes would increase with increasing complexity of the organism according to an evolutionary scheme. However, this is not the case. While a humble bacterium might function with a single chromosome and mosquitoes need 6, humans 46, dogs 78, and goldfish 94, the tropical plant Ophioglossum (snake tongue) has over 1,200. The 46 human chromosomes are organized in two sets of 23 pairs: 22 pairs of autosomes 4 (numbered 1 through 22) plus 1 pair of allosomes 5; XX for female and XY for male. Except for sex chromosomes that determine gender and are thus distinct and different, each set of autosomal chromosomes bears identical copies of the entire human genome, and is inherited as a result of sexual reproduction; one copy from the father, the other from the mother. Indeed, germ cells or gonads (spermatozoid or sperm for short in males, ovum or egg in females) contain only 23 chromosomes: 22 autosomes plus allosome X in a female ovum, and 22 autosomes plus allosome Y or X, in a male sperm. During reproduction the male sperm delivers its entire genetic load, either 22X or 22Y, into the female egg (22X) so that the fertilized egg will contain two identical and complementary pairs of 22 autosomes plus 1 pair of allosomes, either XX or XY. Women’s cells contain 44XX where one X allosome is inherited from each parent, whereas in men’s (44XY), the X allosome derives from the mother and the Y allosome comes from the father, who therefore is the parent that determines the gender of the offspring, whether male or female. Genetic alterations or mutations are associated with over 4,000 human diseases, including cancer, and have been mapped to specific chromosomes, as illustrated in Fig. 3.4 [145].

Fig. 3.4

Gene-associated disorders and traits detected on chromosome 1 (Reproduced from DOE Human Genome Project [146])

Alterations of any of the 22 autosomal chromosomes are associated with autosomal diseases, such as sickle cell anemia. Aberrations in sex chromosomes (X or Y) lead to sex-linked diseases such as hemophilia A. Genetic alterations involving major structural chromosomal abnormalities, such as multiple copies of a chromosome (as seen in Down syndrome), translocation of part of a chromosome to another (as occurs in Burkitt’s lymphoma), or deletions of a chromosome or parts thereof (exemplified by the DiGeorge syndrome), are visually detectable under the microscope. This is because appropriately stained chromosomes acquire light and dark transverse bands (reflecting variations in amounts of A-T or G-C base pairs) that enable cytogeneticists to identify each individual chromosome (Fig. 3.5), and recognize structural abnormalities [147]. This test, called chromosome banding, is used routinely in the clinical setting. More subtle defects can now be detected via more sophisticated approaches, including molecular techniques.

Fig. 3.5

G-banded human male chromosome (Courtesy of Dr. K. Satya-Prakash)

Chromosomal analysis is of great clinical interest because many chromosomal abnormalities are linked to a number of disorders, including mental retardation, infertility, and cancer. Cancer management is impacted by chromosomal analysis because some cancers, especially hematologic malignancies, harbor structural chromosomal abnormalities that have diagnostic or prognostic significance. In fact, a small number of chromosomal abnormalities are virtually diagnostic by themselves. They include t(9;22), the so-called Philadelphia chromosome (Fig. 3.6), the hallmark of chronic myelocytic leukemia (CML) also shared by a small subset of acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), and t(15;17), an abnormality that is specific for acute promyelocytic leukemia. Beyond its diagnostic value, the t(9;22) translocation confers a growth advantage to CML cells that led to the development of Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec®), the first successful post-genomic molecularly targeted agent to control rather than kill malignant cells. However, most cancers exhibit either no chromosomal abnormalities detectable by current methodology, as is the case with most solid tumors, or exhibit non-specific but diagnostically and prognostically helpful abnormalities, as is the case with most hematologic malignancies. Examples of these include gene translocations, such as t(14;18) in follicular-type lymphoma, t(8;14) in Burkitt’s lymphoma, trisomy 12 (three copies of chromosome 12) in CLL, and del(16)(q22) in a subset of acute myelocytic leukemia (AML). Additionally, many genetic aberrations are sub-microscopic, precluding their visual detection by chromosomal banding. Such cases can be unmasked by more powerful techniques that use DNA probes such as FISH analyses [148], comparative genomic hybridization [149], spectral karyotyping [150], recombinant DNA techniques [151], and others [152]. One example of sub-microscopic chromosomal abnormalities is point mutations that characterize certain hemoglobinopathies, where single amino acid substitutions occur on one of the four hemoglobin chains. To illustrate, sickle cell disease and hemoglobin C, two hemoglobinopathies with different symptoms, clinical profiles, and prognoses, result when glutamic acid on position 6 of the β chain is replaced by valine or lysine, respectively.

Fig. 3.6

Diagram and G-banding (L) & R-banding (R) of 9:22 translocation in CML (Courtesy of Dr. Avery A. Sandberg)

3.1.2.4 The Cell Cycle

Cells undergo two fundamentally different but complementary processes: cell cycle and cell differentiation. Cell division, which occurs via the cell cycle, ensures self-renewal of undifferentiated precursor cells, also called stem cells. In contrast, cell differentiation is designed to generate highly specialized non-dividing mature cells with distinct and varied functions. Together, these genetically controlled cellular processes sustain the structural and functional integrity of the entire organism and ensure genetic transfer to the next generation. For example, bone marrow stem cells possess the ability to divide, thus ensuring a constant pool of self-renewing precursor cells. However, stem cells also give rise to a diversity of progenitor cells that, while losing self-renewing potential, undergo differentiation into various types of cells capable of carrying out highly specialized functions. These include red cells to ensure oxygen delivery to all tissues, white cells to seek, engulf, and kill invading microorganisms, and platelets to instantly plug any vascular leak as our first line of defense against accidental blood loss. Both cell division and cell differentiation are highly regulated processes necessary to fulfill their respective functions. For instance, many more bone marrow stem cells must enter into differentiation to produce platelets, with a T1/26 of 7 days, than to produce granulocytes or red blood cells with a T1/2 of 36–48 h and 120 days, respectively. Such stem cells are pre-committed to differentiating into each cell type in contrast to pluripotent stem cells, which are the source of all cell lines in some tissues or organs. Some pre-committed cell lines do not cycle or differentiate until the proper conditions are met. An illustrative case is that of memory T-lymphocytes that remain in G0 (see below) until they are awoken by re-exposure to the original antigen trigger, when they re-enter G1 in order to replicate in an explosive manner so as to confer swift protection from the antigen’s pathogenic effects.

The cell cycle is divided into two major phases visible under the microscope: M-phase (mitosis or cell division) and Interphase [153]. The M-phase comprises prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase, whereas the Interphase includes the S-phase (DNA synthesis), G1, and G2 stages or gaps between M and S, and between S and M, respectively, where cells remain metabolically active in preparation for the next phase. For rapidly proliferating human somatic7 cells that typically exhibit a total cycling time of 24 h, the M-phase lasts approximately 1 h, with most of the cell-cycling time being spent in Interphase, and G1, S, and G2 phases lasting approximately 11, 8, and 4 h, respectively [154]. Cells out of cycle are said to be quiescent or in G0 and require external stimuli to move out of G0 and into G1 [155]. In animal cells, this step is triggered by growth factors that might include epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblastic growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) or by exposure to antigens each binding to receptive cells’ specific surface receptors, but also hormones entering such cells. Once in G1, cells must pass through a restriction point to enter the S-phase, without which they will remain dormant, though metabolically active, until the proper growth factor becomes available. Alternatively, many cells remain in G0 for extended periods of time until the need arises to replace injured or dead cells as occurs in kidney, liver, and other internal organs. Other cells remain permanently in G0, as is the case of neurons. The different events that occur in each phase of the cell cycle must be exquisitely coordinated with one another to ensure their completion in a proper sequence to prevent an aberrant cell division from transferring incomplete or defective copies of genetic material to daughter cells. Such coordination is ensured by checkpoints and feedback controls (Fig. 3.7). An important checkpoint occurs in G2 that, upon detecting unreplicated DNA sequences, blocks cells in G2 and prevents their progress through the M-phase, allowing both repair of DNA damage to take place and orderly completion of the S-phase. Cell cycle checkpoints are under the control of numerous genes that promote or inhibit the cell cycle depending on whether or not defective DNA-carrying cells must be repaired or eliminated. In broad terms, genes that ensure genomic integrity during the cell cycle are called tumor suppressor genes and include caretakers that prevent genomic instability and mutations from occurring, and gatekeepers that regulate cell cycle progression and maintain genomic stability by inducing apoptosis8 or senescence9 on genomically aberrant cells before they become cancer cells [156]. Of these, RB1 and TP53 are considered the main cell cycle gatekeepers through the activity of their encoded proteins, pRB and p53. Their role is exerted through the E2F1, a protein that acts as a transcription factor that promotes cell-cycle progression from G1 to S. In normal cells, E2F is inhibited by pRB, which in turn can be temporarily inactivated by cyclin-dependent kinases of the m2m gene product. In cancer cells, the gene encoding TP53 is often mutated, which prevents G1 arrest in response to DNA damage and allows damaged DNA to both replicate and be delivered to daughter cells. pRB is inactivated by several mechanisms, including loss of function, mutations, and by viral oncogenes, enabling E2F-driven excessive cancer cell proliferation. Mutated RB1 are a cause of childhood retinoblastoma, bladder cancer, and osteogenic sarcoma. p53, a protein encoded by tumor suppressor gene TP53 (located at 17p13.1), is believed to have a far-reaching role, and is sometimes called the guardian of the genome. It includes activation of genes that control the cell cycle (WAF1 and CIP1/p21), DNA damage repair (GADD45), G1 to S and G2 to M progression (14-3-σ), and apoptosis (BAX). Loss of the latter function is generally viewed as a common pathway in carcinogenesis. TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human somatic cancers, and is responsible for the Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a rare inherited condition associated with a high risk for developing sarcomas, brain tumors, breast cancer, and leukemias [157]. Standardized nomenclature is being assigned to human genes in order to bring uniformity in scientific communications and data retrieval. This will prevent past cacophony in this field. For instance, synonyms for the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) include ARF, CDK4I, CMM2, INK4, INK4a, MTS1, p14, p16, p16INK4a, p19, and p19Arf [158].

Fig. 3.7

Cell cycle regulation (Courtesy Dr. S. Collins)

3.1.2.5 Programmed Cell Death

Like organisms, cells are born, live, and die. Also like organisms, cells can die of accidental or natural causes. Accidental cell death is caused by exposure to injurious stimuli, such as excessive heat, acid, radiation, or hypoxia against which cells play an entirely passive role. In contrast, natural cell death is the result of a highly complex but controlled process called programmed cell death that includes apoptosis, which is genetically induced. Cell survival is also controlled by a stretch of DNA located at the end of each chromosome, called telomeres. These two major pathways to cell death control cells’ life span through distinct mechanisms. Apoptosis occurs when a cell commits ‘suicide’ in response to external signals that challenge and ultimately defeat its self-preservation mechanisms. In contrast, telomere-triggered cell death originates from within the cell as a mechanism that inherently limits its life span and by extension controls aging of the entire organism.

Apoptosis

Unless counterbalanced, cell division could result in the accumulation of so many cells that the mass of an organism could nearly double each year. The necessary counterbalance is achieved through natural cell death, mainly apoptosis that maintains cell populations at equilibrium. Cell death also occurs through necrosis, desquamation, and sloughing off of cells lining hollow organs such as the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and genitourinary tracts, and through accidental cell death, which accounts for a marginal fraction of overall cell death. Unlike natural cell death, accidental cell death is a process caused by an acute injury that destroys the cell, spills its content, and triggers an inflammatory response. On the other hand, apoptosis can be viewed as a cell implosion from within, with rapid clearing of cell debris by specialized cells called macrophages, without causing inflammation. “The role of apoptosis in normal physiology is as significant as that of its counterpart, mitosis. It demonstrates a complementary but opposite role to mitosis and cell proliferation in the regulation of various cell populations” [159]. Apoptotic cells are recognizable by light microscopy “as round or oval masses with dark eosinophilic cytoplasm and dense purple nuclear chromatin fragments” [160], with subcellular changes being identified by electronic microscopy. The process of apoptosis follows two main apoptotic pathways: the extrinsic or death receptor pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway. A third pathway involves T-cell mediated cytotoxicity and perforin-granzyme-dependent cell killing, all converging at the execution pathway [161]. The extrinsic pathway involves transmembrane receptor-binding interactions where cell membrane TNF10 or the death receptor is bound by death receptor ligands FasL/FasR, TNF-α/TNFR1, Apo3L/DR3, Apo2L/DR4, or Apo2L/DR5, initiating transmission from the cell surface to the intracellular death domain, of the signal that activates caspase-8, which in turn activates caspase-3 that triggers the final execution pathway. In contrast, the intrinsic pathway involves a variety of non-receptor-mediated stimuli that activate intracellular signals that cause mitochondrial events that can be positive or negative: e.g., promote or suppress apoptosis, respectively. Regulation of apoptotic mitochondrial events occurs through members of the 25 BCL-2 gene family encoding at least 14 proteins that promote apoptosis, such as Bcl-10, Bax, Bak, Bid, Bad, Bim, Bik, and Blk, or suppress it, including Bcl-2, Bcl-x, Bcl-XL, Bcl-XS, Bcl-w, BAG [162]. It has been reported that the interaction of some of these proteins bound to each other determines whether the resulting dimer promotes or blocks apoptosis. For example, the Bax/Bax and Bcl-2/Bad dimers promote cell death, whereas Bax/Bcl-2 and Bcl-2/Bcl-2 dimers protect against it. A myriad of triggers can initiate the apoptotic pathway, including chemotherapy drugs, ultraviolet and gamma irradiation, oxidative agents, certain viruses, and various cytokines.11 In addition, cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) exert their cytotoxic activity through the extrinsic pathway via FasL/FasR interactions, but also via the secretion of Perforin that involves serine proteases granzyme A and granzyme B, with the latter acting directly on caspase-3 or indirectly via caspase-10 [163]. CTLs play a pivotal role in the immune surveillance mechanism said to prevent cancer from emerging by inducing tumor cell apoptosis. Regardless of the pathway taken, once initiated, the apoptotic process culminates in the activation of caspases, a family of cysteine proteases,12 by cleaving a variety of cytoplasmic, nuclear, and membrane proteins, the final steps of the apoptotic pathway (Table 3.2). Abnormalities in apoptosis are thought to play an important role in a number of diseases, including cancer.

Cancer cells can escape apoptosis through a variety of mechanisms including over-expression of BCL-2, mutated P53, down-regulation or non-functioning Fas receptors on tumor cells, among others. One example is the BCL-2, discovered in 1985 because of its involvement in chromosome translocation t(14;18), that is detected in 90 % of follicular-type non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [165]. This translocation places the BCL-2, normally located on chromosome 18, under the influence of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene locus situated on chromosome 14, resulting in overproduction of BCL-2 protein and prolonged survival of the malignant cells. The t(14;18) was the first gene found to contribute to tumor growth by reducing cell death rather than by promoting cell division, a major breakthrough that suggests a new strategy for combating cancer. Indeed, it can be envisioned that manipulation of the pro- and anti-apoptotic forces to favor the former might restore the normal apoptotic process lost during tumorigenesis, thus removing the survival advantage of malignant cells.

Telomeres

At the end of each chromosome lies a unique stretch of repeated sequences of TTAGGG on one strand of DNA bound to AATCCC on the other strand of approximately 10,000–12,000 base pairs in length associated with a protein complex named shelterin that protects chromosome ends, called telomeres [166]. These sequences do not contain genetic codes, but are critical to the aging of normal cells and to the apparent inexhaustible ability of cancer cells to replicate [167]. Telomeres are sometimes referred to as the cell clock or counting mechanism because they limit the number of divisions a normal cell can undertake. When a normal cell divides, the ends of chromosomes cannot be replicated and 50–200 telomere base pairs are lost with each division, progressively reducing the length of telomeres. Eventually, once somatic cells lose their entire telomere sequences, after multiple replication rounds, they can no longer divide and enter the phase of replicative senescence and apoptotic cell death. This is because telomerase, an enzyme that restores and maintains telomere length in undifferentiated cells, such as stem, germ line, hematopoietic, and other rapidly dividing cells, is absent or nearly absent in normal somatic cells. Yet, telomerase levels also decrease in aging normal stem cells, resulting in progressive shortening of telomeres, contrary to the persistently high levels of telomerase reported in most human malignancies [168]. While increased telomerase activity in malignant cells sustains their replicative capacity, a property that could be exploited therapeutically, it is not involved in the development, growth, or dissemination of cancer, except in rare cells that remain telomerase expression capable [169].

Telomeres and telomerase appear to play a role in human aging [170] that might be influenced by lifestyle factors [171]. The possible link between telomere length and survival is supported by knockout mice 13 data and by a rare human disease. Knockout mice give rise to offspring whose life span is dependent on the length of their telomeres. Likewise, dyskeratosis congenita, a fatal X-linked human disease associated with decreased RNA telomerase, decreased telomerase activity, and shorter telomeres, exhibits age-dependent chromosomal abnormalities and an increased tendency to develop malignancies. Finally, while increased telomerase activity is detected in 94 % of neuroblastomas, a mainly childhood cancer, low or undetectable telomerase levels are found in a disease subset called neuroblastoma 4S. Children afflicted by neuroblastoma 4S exhibit an astonishingly high rate of spontaneous remission, reaching 100 % in one study, a behavior not seen with any other cancer [172, 173]. Spontaneous remission in these patients is associated with a lack of telomerase expression [174]. Together, these compelling observations have led a number of research laboratories and biotechnology companies actively to study telomerase as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic target. Indeed, it is tempting to contemplate the possibility that manipulation of a single molecule, whether telomeres or telomerase, might one day prolong the lifespan of normal cells, slow the aging process, and control cancer progression by eliminating the survival advantage of malignant cells. Nevertheless, to date, most studies are based on pooled cancer cells that yield average results, which must be interpreted with caution in light of the increasingly appealing cancer stem cell model of tumors where a small subset of stem cells is understood to,

In conformity with this view, gene expression profiling of single circulating tumor cells (CTC) in breast cancer patients confirmed the heterogeneity of such non-tumorigenic, non-dividing cancer cells, and demonstrated that these cells belong to subpopulations fundamentally different from pooled cells obtained from the primary tumor [176].

constitute a reservoir of self-sustaining cells with the exclusive ability to self-renew and maintain the tumor. These cancer stem cells have the capacity to both divide and expand the cancer stem cell pool and to differentiate into the heterogeneous non tumorigenic cancer cell types that in most cases appear to constitute the bulk of the cancer cells within the tumor [175].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree