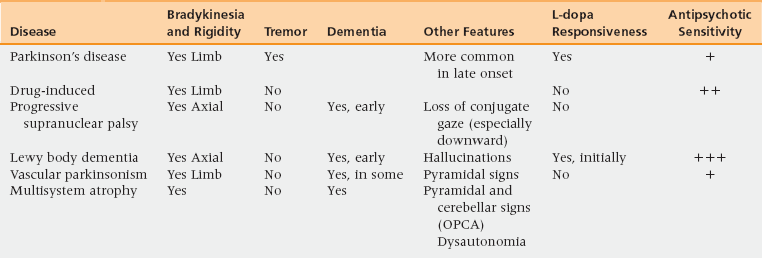

52 Upon completion of this chapter the reader will be able to: • Define and recognize the clinical features that justify a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD). • Describe the differences in clinical features and medication responsiveness of the illnesses from which PD must be differentiated, including other Lewy body disorders. • Understand the role of levodopa in diagnosis and treatment and the indications for the use of adjunctive medications in PD in older persons. • Recognize and optimally manage the motor and nonmotor complications of PD. PD is characterized by rigidity, tremor, and bradykinesia; it is usually asymmetric and is usually responsive to dopaminergic treatment. Familial PD is described. Parkinson-plus syndromes refer to disorders that include parkinsonism with other clinical signs: they include dementia of Lewy body type (LBD), multiple system atrophy (MSA), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and corticobasal degeneration.1 As in other industrialized countries, the prevalence is approximately 1% in persons over 65 in the United States, and rises to 3% in those over 85.2 All ethnic origins can be affected, males somewhat more than females.3 Role of Aging: Although the incidence of PD increases with age, PD is generally not considered a normal part of aging. Genetic Predisposition: Most people with PD do not have a family history, but 15% do have a first-degree relative with PD, characteristically without a clear mode of inheritance.4 Several genetic loci for PD are identified, although a common environmental etiology could explain familial patterns.5 Role of Environmental Exposure: Pesticides, rural environments, and well water have all been linked to PD.6 In the early 1980s, a perthine analog was reported: it is the only environmental agent directly linked to levodopa-responsive parkinsonism. Cigarette smoking may actually lessen the risk!7 Trauma: Parkinsonian features are seen in head injury, including boxers and football players, and also in cerebrovascular disease, both presumably due to damage to the basal ganglia. Parkinson’s disease in any one individual is likely to represent several factors acting together. The underlying pathologic change in PD is injury to the dopaminergic projections from the substantia nigra pars compacta to the caudate nucleus and putamen. Intraneuronal Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites are other pathological features of PD. Lewy neurites are often observed in the cortex, amygdala, locus coeruleus, vagal nucleus, and the peripheral autonomic nervous system8; this could explain some of the nonmotor features of PD. Whereas autopsy is required to make the definitive diagnosis of PD, an accurate clinical diagnosis can usually be made based on the classical features that Parkinson originally described, plus other features that, over the years, have been recognized to be associated with PD.9 Four cardinal features are listed in Box 52-1. Since some of these features are frequently seen in older patients, the diagnosis of PD should be considered when at least two of the four are present. Significant supportive motor features are listed in Box 52-2. Because levodopa or a dopamine agonist usually provides improvement in the motor manifestations, a definite response to levodopa is regarded as a confirmatory test and is required for a diagnosis of probable (that is, clinically definite) PD.10 Although L-dopa responsiveness can help differentiate classical PD in most instances, an initial response to levodopa can occur in Parkinson-plus syndromes such as LBD and multisystem atrophy. However, the sustained response to levodopa is confirmatory of PD, and it is the motor features that are most improved. In the NINDS Diagnostic Criteria for PD (see Chapter 17), the features summarized in Box 52-3 are considered suggestive of other diagnoses than PD; that is, are evidence that something other than PD is going on, and so—we would advise—might lead the PCP to seek neurologic or other consultation, except perhaps in the case of the relationship of the PD symptoms to a dementia process, and thus the consideration for Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), a diagnosis which the PCP should be the one to make! (See Chapter 17 on Alzheimer’s and other dementias.) The NINDS criteria require a confirmatory autopsy for PD to be described as “definite” but would rate PD as “probable” if three of the four clinical features (see Box 52-1) were present for three years, with none of the features listed in Box 52-3, and if there had been a sustained, definite response to L-dopa (or a dopamine agonist); “possible” PD would require only two of the four primary features (Box 52-1) (provided one of the two were bradykinesia or tremor), would not require the medication responsiveness if an adequate trial had not yet taken place, and—if symptoms had been present for three years—one or more of the findings which suggest other diagnoses (Box 52-3) could be present. Resting tremor, pronation-supination or pill-rolling, in character with a frequency mostly of 4 to 6 Hz (9) is the first symptom in 70% of PD patients. Tremor is characteristically asymmetric at onset and worsens with anxiety, with contralateral motor action, and with ambulation. Muscular rigidity is resistance noted during passive joint movement in the normal range of motion of that joint. It usually has a cogwheeling feel. It is often more prominent in the most tremulous extremity. Rigidity is increased by contralateral motor movement or a mental task. Bradykinesia causes the most dysfunction in the initial stages of the illness. The patient is unable to perform fine-motor tasks effectively. Observing a patient suspected of having PD walking, tying their shoelaces, or writing a sentence can be helpful in diagnosis. Postural instability onsets insidiously with progressively poor balance. It leads to increased fall risk. It can be demonstrated by testing for postural reflexes by pushing the patient forward (propulsion) or backward (retropulsion) to check for balance recovery. Gait dysfunction is characterized by shuffling, slowness of walking, and by turning “en bloc.” Freezing is shown by difficulty initiating walking or by striking gait hesitation (transient loss of movement), on turning or on arriving at a real or perceived obstacle. Autonomic dysfunction is common and causes bowel and bladder dysfunction, excessive sweating, and orthostatic hypotension.11 However, dysautonomia as an early or particularly severe feature suggests a diagnosis other than PD.9,10 Dementia has been said to develop in about 40% of PD patients,12 although in a study that followed patients until death, it was present in over 80% in the end stage of the illness.13 Thus the PCP must watch for subtle cognitive and other characteristic symptoms of dementia, and patients should be screened for this common syndrome. The concept of PD as part of a spectrum of disorders which includes Lewy Body Dementia (LBD) is a vital one for the PCP to embrace, as this dementia is much more common than has been historically taught and is well within the diagnostic range of the PCP. Currently, there is a “one-year rule” arbitrarily decided upon, that, if PD symptoms and/or signs have existed for at least one year before signs of dementia, the Dx is PDD (Parkinson Disease dementia), whereas if dementia occurs first or the PD symptoms and signs have been apparent for less than a year before the dementia, it is–for now–regarded as LBD. Whereas LBD is often characterized by vivid visual hallucinations, any dementia predisposes patients treated with anti-parkinsonian drugs to hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms. Depression is common in PD, affecting nearly half of patients.14 Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be effective, and the dopaminergic qualities of sertraline can be therapeutic but can also complicate levodopa dosing. Sensory symptoms in PD are quite varied and include anosmia and paresthesia, and pain.15 Disturbed sleep is common. Causes include nocturnal stiffness, nocturia, depression, restless legs syndrome, and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep behavior disorder (RSBD)—another LBD hint.16 Essential tremor is the most common tremor and tends to be familial. It typically is first noted when it interferes with eating17 as it is characteristically a terminal intention tremor, occurring with voluntary movement, as can usually be shown in the finger–nose test. It is also absent at rest and tends to be bilateral; it is frequently asymmetric. It has a higher frequency range (5 to 10 Hz) than the typical tremor in PD; in older patients, the frequency is in the lower range. In advanced cases, essential tremor can be present at rest and thus confused with PD; and a patient with PD can have both! If rigidity and bradykinesia are present, a trial of levodopa may be appropriate. The following differential diagnoses are summarized in Table 52-1. TABLE 52-1 Distinguishing Parkinson’s Disease from its Differential Diagnosis From: Chan DK. The art of treating Parkinson’s disease in the older patient. Aus Fam Physician 2003;32:927-931.19

Parkinson’s disease

Prevalence and impact

Risk factors and pathophysiology

Pathology

Differential diagnosis and assessment

Is it parkinson’s disease?

Levodopa responsiveness

Motor features

Nonmotor features

Differential diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Parkinson’s disease