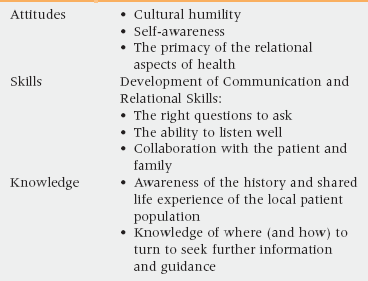

5 Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the core attitudes/skills/knowledge of advanced cultural competency (ACC). • Consider how the experience of dementia is shaped by each subculture’s concept of what makes a person a person. • Recognize that acknowledging and exploring the nature of health care disparities is necessary to achieve ACC, and that seeking to understand one’s own internal biases is an integral part of this effort. • Discuss the model of offering truth, and possible scripts for sharing end-of-life information respectfully. • Realize that health beliefs may shed some light on but are never sufficient to explain patient preferences and behavior, and that it is critical to consider the patient and his or her community’s personal and historical experience and perception of health care. Special Thanks to Sharon Kaufman, Mary Jo Del Vecchio Good, Lawrence Cohen and Paul Farmer, who have been tremendous mentors and allies throughout my journey as a clinician-anthropologist. The importance of cultural competency is widely accepted as fundamental to quality care1,2 and increasingly is seen as essential to combating health care disparities and in providing high-quality health care to all.3–7 However, at the same time, there are few rigorous studies regarding the efficacy of cultural competency training,8,9 and there are many critiques of cultural competency as it is often defined and taught.10–15 Conventional cultural competency training implies that one can master a body of knowledge to become culturally competent.16,17 However, competency as a goal is inherently flawed because cultures are complex and varied. Assuming that a clinician can be competent in understanding other cultures is naive and implicitly leads to oversimplification and stereotyping, objectification of the patient, and failure to develop valuable, generalizable skills. Table 5-1 identifies the key attitudes, skills, and knowledge of advanced cultural competency. The remainder of this chapter presents case scenarios that demonstrate how these factors interact and can be applied in common geriatric situations. The dominant cultural approach to dementia in the United States reflects the cultural definition of an intact person as a person with value; the focus of achieving full personhood is on independence and achievement.18–21 In contrast, other cultures may value more highly such qualities as interdependence, spiritual connection, embodied activity, or social relationships and role.22–25 In the above case, we see that Ms. Nettie Mae is still valued as a full person because she still is the family matriarch. The role as a surviving elder is honored as an embodiment of the community’s history and the community’s ability to survive in a fairly hostile environment (e.g., slavery, Jim Crow, Civil Rights struggles, ongoing structural and institutional racism in the contemporary United States). Finally, her personhood endures because she still is able to participate interpersonally and emotionally with family and community members. Indeed, we increasingly recognize that emotional and relational abilities persist far into the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Therefore, when personhood is defined as the ability to relate to others appropriately, dementia is less of a threat to the patient’s personhood. In contrast, by narrowly defining full personhood as independence and cognitive achievement, the dominant U.S. cultural approach to personhood leads to excess disability and suffering.26 Disparities are a significant and persistent issue in our health care world. The evidence base documenting the pervasive reality of health care disparity is voluminous and spans every organ system and medical subspecialty.27 For example, the undertreatment of pain in patients of color is well documented. Latinos with long bone fractures in a Los Angeles emergency department, for example, did not receive the same pain medication given to Caucasians with the same fractures.28 A similar study in Atlanta confirmed that African Americans with long bone fractures received less pain medication than Caucasians.29 Increasingly, we recognize that clinical thinking and decision making are influenced by clinical biases.30–33 When studies control for insurance, economic class, socioeconomic status, and education, a stubborn persistence of health care disparities remains, most strikingly along axes of race and ethnicity, but also along axes of gender and age.27 Advanced cultural competency, by recognizing equity as essential to quality care, always seeks to address the complex processes that lead to health care disparities. There are many reasons that U.S.-born African Americans tend to elect full code status, even in terminal or end-stage disease processes. As already stated, personhood may not be thought to be lost when someone has significant functional deficits. Furthermore, the preservation of life for its own value is elevated in the African American community, in part for spiritual/religious reasons,34–36 but also because the “will to live” carries value in the context of the challenges it takes to survive and thrive in the relatively hostile context of the historical and contemporary United States. What do I mean by the will to live? Consider this: As a geriatrician, several years ago I was invited to speak to a community group of Holocaust survivors. These were all individuals who had survived concentration camps in large part because of their strong will to live (e.g., their personal willingness to endure a great degree of suffering and discomfort, in order to remain alive). They were not particularly interested in exploring with me the option of choosing to come to the end of their life. They had already surmounted tremendous odds against life and this served as a meaningful reference point for them when new life challenges appeared. Similarly, many African Americans have faced, and continue to face, tremendous obstacles in the United States, and those who survive into their elder years often have done so because of a tremendous will to live. The option of “giving up” is not considered acceptable, and a growing body of ethnographic research indicates that for most patients, the decision to implement a do not resuscitate (DNR) order or engage Hospice care is generally perceived as symbolic of giving up and choosing death.37,38 Finally, as will be discussed further later in the chapter, the African American historical and contemporary experience of health care results in a logical mistrust, a feeling that the health care system is very likely to not provide the best possible care to them, solely because they are African American.39–41 The U.S. attitude, however, is an unusual anomalous cultural approach to the relationship of individuals to their own death. Even though all involved may be tacitly aware that death appears imminent, the vast majority of cultures and subcultures in the world consider it far more appropriate and beneficial to focus on living, on hope, and to avoid the topic of the individual’s death.42–44 Professor Han is, therefore, more typical of the world’s populations; many if not most communities believe that discussing someone’s potential death is dangerous and does the person harm.45,46 If, as in Professor Han’s case, the patient and family consider that talking about death is dangerous and pathogenic, you might do well to recognize and consider the nocebo effect (Box 5-1). A nocebo effect occurs when, because of pessimistic beliefs and expectations, a patient has an adverse reaction to an inert or innocuous treatment (i.e., the inverse of the placebo effect).47–49 In this case, a well-intentioned action on the part of the health care team can lead to patient harm.50

Advanced cultural competency in caring for geriatric patients

Defining cultural competency

Dementia, personhood, and culture

Health care disparities

Palliative care and “giving up”

Talking about dying

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Advanced cultural competency in caring for geriatric patients