Cancer of Unknown Primary

Nicholas James Hornstein

Ryan Huey

Kanwal Pratap Sing Raghav

Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) represents a heterogeneous group of metastatic cancers wherein the primary site of origin eludes detection despite adequate and recommended diagnostic workup (1,2,3).

Although CUP is a well-recognized clinical entity characterized by an unusual pattern of metastatic spread distinct from other cancers with known primaries, the central oncogenic mechanisms that underlie this “atypical cancer syndrome” are unclear to date.

Consequently, the controversy regarding the validity of CUP diagnosis persists: irresolutely between CUP being an erroneous diagnosis because of inadequate diagnostics to detect a primary lesion and being a distinct biologic entity sharing molecular features (4,5).

Although early transcriptomics showed CUP to be discrete from metastases of known origin, the range of genomic aberrations appears to be similar and shared between both entities (6,7).

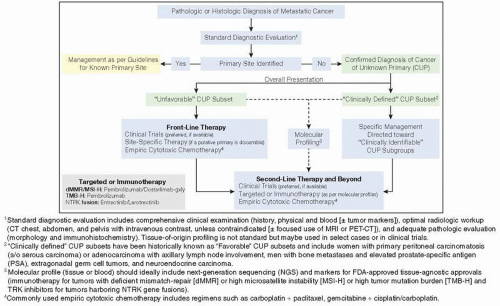

These conflicting views are reflected in the differing management paradigms for this disease, expressly separated into two camps: “site-specific therapy” wherein treatment is modeled after the most likely putative primary and “empiric chemotherapy” with combined broad-spectrum cytotoxic chemotherapy, notably carboplatin and paclitaxel (Figure 7.1).

Regardless of genesis, patients with CUP present a challenge in oncology clinics because of the heterogeneity of presentation, complexity of diagnostic workup, and few treatment options.

Although the era of molecularly targeted therapies and immunotherapies has seen significant advances in systemic therapy for cancers with known primary, progress in CUP has lagged because of limited CUP-specific research and exclusion from tumor-specific clinical trials.

In this chapter, we will review the current management of CUP and the promise of novel targeted and immune therapies in the treatment of this poorly understood and orphan disease.

Epidemiology and Prognosis

Because of advances in imaging, pathology, and molecular profiling, the incidence of CUP has declined over the past few decades (8). Cancers traditionally misdiagnosed as CUP, such as cholangiocarcinoma, germ cell tumor, and certain sarcomas, are increasingly distinguished from CUP with improved immunohistochemistry, cytopathology, and molecular diagnostics.

CUP is a rare cancer with an incidence of 4 to 6 cases per 100,000 population in the United States and constitutes roughly 2% of all cancer diagnosis (8,9). An estimated 32,880 new cases of CUP will be diagnosed in the United States annually (10). This grouping of “CUP patients” is a mix of tumors with diverse histologies and varying biology and clinical behavior.

CUP is classified into broad histologic categories based on light microscopy; adenocarcinoma of unknown primary (ACUP) is most frequent, representing about 70% to 75% of CUP cases, whereas squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary (SqCUP) and undifferentiated carcinoma constitute approximately 6% to 9% and 25% to 35% of all CUP cases, respectively (8,11,12).

With limited therapeutic options, the overall prognosis of patients with CUP has remained poor (8). Globally, the median survival of all patients with CUP ranges from 2 to 3 months (8,11,12).

Survival is strongly dependent on histology, with 1-year survival rates of 15% to 17% for ACUP to 53% for SqCUP (8). Corresponding 5-year survival rates are 6% and 41%, respectively (8). Sarcomatoid CUP (SCUP) is another aggressive histology with poor overall survival (13).

Additionally, other factors like gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), histology, number of metastatic sites (and sites of metastatic spread), and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio also impact prognosis (8,11,12,14). Clinical subsets such as lymph node-only disease (LNCUP) have a better overall survival (median: 33 months) compared to those with bone-predominant (BCUP) disease (median 15 months) or patients with other CUP (median: 16 months) (15).

Molecular Profiling and Tissue (Site) of Origin

Historically, CUP was regarded as a distinct form of cancer, related more biologically than anatomically, and treated as such with empiric therapy (16,17,18,19,20). Over the years, there has been a shift in this belief toward the notion that CUP may be a metastatic cancer syndrome wherein the metastatic tumors may retain the essence of their original tissue of origin (ToO) (21,22).

Pathologic evaluation, especially tumor-specific immunohistochemistry, is commonly used for labeling CUP, vis-à-vis tumor lineage and identifying a primary site, though this strategy is not helpful in all patients because of limits of sensitivity and specificity of various markers (23,24,25).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree