Esophageal and gastric cancers are common malignancies, both in the United States and worldwide, that carry significant morbidity and mortality. Malnutrition is a common complication in patients with esophageal and gastric cancers and it portends a poor prognosis. For patients who undergo surgical therapy for these types of cancers, preoperative and postoperative nutritional optimization have been shown to improve outcomes. The support can be accomplished in different manners, including orally, enterally, or parentally. In patients who do not undergo surgery but receive chemotherapy and/or radiation, nutritional support is also an important aspect of the multidisciplinary care approach.

Key points

- •

Malnutrition is a common complication of esophageal and gastric cancers.

- •

Nutritional support is an important aspect of the multidisciplinary care that patients with these cancers require.

- •

For patients who undergo surgery, nutritional optimization before surgery has been shown to improve outcomes.

- •

Whenever possible, enteral nutritional support is preferred to parenteral nutrition.

- •

Nutritional support, either enteral or parental, carries the risk of complications and these should be weighed against the possible benefits when determining the appropriate management course.

Introduction

Malnutrition is a common complication of esophageal and gastric cancers and it is associated with poorer outcomes. It can occur through multiple mechanisms, including increased metabolic demands, insufficient nutrient intake, or nutrient loss. More specifically, these patients often have poor nutritional intake because of dysphagia, cancer cachexia, surgical resections and their complications, unresectable disease, strictures, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy effects. For these reasons, nutritional support is a critical aspect of the multidisciplinary treatment required by these patients. For clinicians, malnutrition can be defined as an abnormal body composition with functional impairment of organs, caused by an acute or chronic imbalance between energy and protein availability and body requirements. Cancer cachexia is an important aspect of these patients’ malnutrition. It has come to carry multiple definitions, but recently Bozzetti and Mariani defined it as a complex syndrome characterized by a severe, chronic, unintentional, and progressive weight loss, which is poorly responsive to the conventional nutritional support, and may be associated with anorexia, asthenia, and early satiation. Hence the management of malnutrition and cancer cachexia in these patients is best accomplished via a multidisciplinary approach that includes clinical nutritionists, dieticians, gastroenterologists, medical oncologists, and surgeons.

In general, these patients can be classified into 2 groups: operable and nonoperable. The nonoperable patients can be further subdivided into those who will undergo chemotherapy and/or radiation and those who will receive palliative measures only. Each group of patients faces its own set of obstacles to maintaining adequate nutrition and each group requires a specific approach to nutritional support. For those patients who undergo surgery, there is a significant associated morbidity. Undergoing surgery in a malnourished state increases the risk of morbidity. In these cases, nutritional support is an essential aspect of the patient’s preoperative and postoperative management. For patients who do not undergo surgery but instead receive chemotherapy and/or radiation, nutritional support is also critical. These therapies can be very toxic to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and negatively affect the patient’s nutritional status. Early nutritional support should be provided when necessary.

Patients who undergo terminal or hospice-based care can present difficult ethical dilemmas regarding their nutrition. Patients and their families may see withdrawal or withholding of nutritional support as hastening death; however, studies have routinely shown that nutritional support in these patients provides no benefit ( Box 1 ).

Malnutrition

Abnormal body composition with functional impairment of organs, caused by an acute or chronic imbalance between energy and protein availability and body requirements.

Cancer cachexia

A complex syndrome characterized by a severe, chronic, unintentional, and progressive weight loss, which is poorly responsive to the conventional nutritional support and may be associated with anorexia, asthenia, and early satiation.

Enteral nutrition

Providing caloric needs via the GI tract by way of introducing formula either with an nasogastric tube or through percutaneous tubes such as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy.

Parenteral nutrition

Providing caloric needs via an intravenous solution, which typically contains dextrose, amino acids, lipids, electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals.

Introduction

Malnutrition is a common complication of esophageal and gastric cancers and it is associated with poorer outcomes. It can occur through multiple mechanisms, including increased metabolic demands, insufficient nutrient intake, or nutrient loss. More specifically, these patients often have poor nutritional intake because of dysphagia, cancer cachexia, surgical resections and their complications, unresectable disease, strictures, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy effects. For these reasons, nutritional support is a critical aspect of the multidisciplinary treatment required by these patients. For clinicians, malnutrition can be defined as an abnormal body composition with functional impairment of organs, caused by an acute or chronic imbalance between energy and protein availability and body requirements. Cancer cachexia is an important aspect of these patients’ malnutrition. It has come to carry multiple definitions, but recently Bozzetti and Mariani defined it as a complex syndrome characterized by a severe, chronic, unintentional, and progressive weight loss, which is poorly responsive to the conventional nutritional support, and may be associated with anorexia, asthenia, and early satiation. Hence the management of malnutrition and cancer cachexia in these patients is best accomplished via a multidisciplinary approach that includes clinical nutritionists, dieticians, gastroenterologists, medical oncologists, and surgeons.

In general, these patients can be classified into 2 groups: operable and nonoperable. The nonoperable patients can be further subdivided into those who will undergo chemotherapy and/or radiation and those who will receive palliative measures only. Each group of patients faces its own set of obstacles to maintaining adequate nutrition and each group requires a specific approach to nutritional support. For those patients who undergo surgery, there is a significant associated morbidity. Undergoing surgery in a malnourished state increases the risk of morbidity. In these cases, nutritional support is an essential aspect of the patient’s preoperative and postoperative management. For patients who do not undergo surgery but instead receive chemotherapy and/or radiation, nutritional support is also critical. These therapies can be very toxic to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and negatively affect the patient’s nutritional status. Early nutritional support should be provided when necessary.

Patients who undergo terminal or hospice-based care can present difficult ethical dilemmas regarding their nutrition. Patients and their families may see withdrawal or withholding of nutritional support as hastening death; however, studies have routinely shown that nutritional support in these patients provides no benefit ( Box 1 ).

Malnutrition

Abnormal body composition with functional impairment of organs, caused by an acute or chronic imbalance between energy and protein availability and body requirements.

Cancer cachexia

A complex syndrome characterized by a severe, chronic, unintentional, and progressive weight loss, which is poorly responsive to the conventional nutritional support and may be associated with anorexia, asthenia, and early satiation.

Enteral nutrition

Providing caloric needs via the GI tract by way of introducing formula either with an nasogastric tube or through percutaneous tubes such as percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy.

Parenteral nutrition

Providing caloric needs via an intravenous solution, which typically contains dextrose, amino acids, lipids, electrolytes, vitamins, and minerals.

Epidemiology

In the United States in 2016, esophageal cancer has an estimated incidence of 14,550 new cases and 13,770 deaths are expected. In 2012, there were an estimated 455,800 new cases and 400,200 deaths occurred worldwide. In the United States in 2016, it is also estimated that there will be 22,280 cases of gastric cancer diagnosed and 11,430 deaths are expected. According to the World Health Organization, there were 952,000 new cases of gastric cancer worldwide and 723,000 deaths attributed to the disease in 2012.

Both of these diseases, because of the organs affected and the treatments they often require, are associated with a significant risk of malnutrition. In patients with esophageal and gastric cancers, malnutrition is reported in 60% to 85% of cases.

Malnutrition as a prognostic factor

Malnutrition has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor in patients with esophageal and gastric cancers. In patients with nonoperable esophageal and gastric cancers, Nozoe and colleagues observed that the Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) was independently associated with long-term survival. The PNI is a simple tool, because it only requires the patient’s albumin level and lymphocyte count to be calculated. Andreyev and colleagues also showed that malnutrition was independently associated with poorer outcomes while undergoing chemotherapy. Malnutrition has also been shown to be an independent prognostic factor in patients who undergo surgical therapy.

Nutritional support in operative patients

Patients with esophageal and gastric cancers who undergo surgical therapy face considerable obstacles to maintaining nutrition. Malnutrition in these patients can occur because of the patients’ inability to consume calories because of mechanical limitations caused by the tumors, such as dysphagia, odynophagia, and early satiety. It may be caused by tumor cachexia, as described earlier. In addition, malnutrition can be caused the effects of the surgeries, including early satiety, nausea, vomiting, pain, anastomotic leaks, and infections. For these patients, attention should be paid to nutritional support in the preoperative and postoperative settings, not only to prevent the long-term nutritional impact of the diagnosis but also to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality. In a prospective study, Heneghan and colleagues found that malabsorption and malnutrition were prevalent in patients undergoing curative resections of both gastric and esophageal cancers. A study of 205 patients who had undergone esophagectomy showed that 55% of these patients had lost more than 10% of their initial body weight at 1 year after surgery. At 5 years after surgery, 1-year weight loss was one of 3 factors, along with clinical stage and incomplete surgical resection, noted to negatively predict 5-year disease survival.

For these patients, a comprehensive plan of nutrition support should be in place well before the surgery is performed. Mariette and colleagues proposed that, for patients who cannot consume 75% of their goal calories (typically 25–30 kcal/kg/d), oral supplementation of calories should be performed. The investigators proposed that this can be accomplished through nutritional recommendations or dietetic advice as follows:

- •

Organize a timetable dividing the daily intake into 5 or 6 small meals, eaten in a pleasant environment and with enough time to eat.

- •

Because smaller volumes are tolerated best, food with high nutritional content should be presented in small quantities.

- •

Consider the patient’s preference in relation to the presentation and preparation of the meals. Dietary recommendations to control symptoms frequently associated with esophageal cancer and gastric cancer include the following.

- •

In cases of anorexia: meals and drinks should be nutritionally enriched; give small volumes; take advantage of moments when the patient feels like eating.

- •

In cases of dysphagia: modify the consistency of food and give smaller quantities to ease swallowing and prevent fatigue (which could intensify dysphagia and increase the risk of aspiration); ensure that the patient is in the correct sitting position to ease the progression of the food bolus; avoid food accumulating in the mouth. For dysphagia to liquids, texture should be modified to a gelatinous or creamy consistency; for dysphagia to solids, prepare food with a softer texture.

- •

In cases of mucositis: eat slowly and take foods at room temperature; maintain optimum oral hygiene; give soft and smooth foods, chopped or mixed with liquids or sauces; avoid irritants, such as skins or spicy, acidic, or fried foods. This advice is intended to prevent the pain of mucositis, alleviate the oral dryness caused by a decrease and modification of saliva production, and improve the flavor of the food.

For patients who cannot consume greater than 50% of their nutritional requirements, enteral feeding is recommended. The route of administration of the enteral feedings depends on many factors, including the length of time the patient is expected to remain on enteral nutrition, the location of the tumor, and provider preference. For patients who require enteral nutrition for a limited period of time (<2–3 weeks), a nasogastric (NG) or nasojejunal tube is recommended. For patients who are likely to require enteral nutrition for an extended period of time, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ) is preferred.

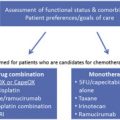

The patients who are not able to meet their nutritional requirements through oral feeding and are not candidates for enteral feeding may benefit from parenteral nutrition ( Fig. 1 ).