Germ Cell Tumors

Taussig Cancer Institute and Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

Multiple Choice and Discussion Questions

1. When staging a man with a disseminated germ cell tumor (GCT), at what time point should serum tumor markers (STMs) be drawn in order to determine his prognosis and stage?

- Prior to orchiectomy

- Following orchiectomy

- On day 1 of cycle 1 of chemotherapy

- Whichever of the above numbers is highest

For men with disseminated GCTs, prognosis should be based on the burden of disease at the time that systemic therapy is started. Therefore, the optimal time to measure serum beta-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is immediately prior to initiating chemotherapy. The analysis used to develop our current prognostic classification and staging of GCTs was based on tumor marker levels at the time that systemic therapy was started.

The STMs beta-hCG and AFP should be drawn prior to orchiectomy but not for prognostic purposes. The STM levels prior to orchiectomy reflect the primary tumor as well as any metastatic disease, and thus are an unreliable indicator of the extent of any disseminated disease. The value of pre-orchiectomy beta-hCG and AFP is twofold: an elevated AFP excludes a diagnosis of pure seminoma regardless of the histopathological findings (unless an alternative, non-GCT explanation for the AFP elevation is established), and having pre-orchiectomy markers facilitates interpretation of post-orchiectomy markers. In other words, if STMs are elevated after orchiectomy, it is helpful to know whether the levels are higher or lower than they were prior to orchiectomy. If beta-hCG or AFP is persistently elevated or rising following orchiectomy, this is indicative of disseminated disease even in the absence of any radiographic evidence of metastases, and the standard treatment is chemotherapy. In contrast to AFP and beta-hCG, the only role for measurement of serum LDH is to establish prognosis at the start of chemotherapy. An elevated LDH may result from myriad different conditions and is often unrelated to the patient’s cancer. There is no clear reason to measure LDH levels before or after orchiectomy unless the patient is going to start treatment with chemotherapy for metastatic disease.

2. Is surveillance the best option for all men with stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs) of the testis?

- Yes

- No

Surveillance is an excellent option for most men with stage I NSGCTs but is not the best option for everyone. It does not make logical sense to choose surveillance if the patient will not be able to comply with the surveillance schedule. There may be psychological, economical, geographical, or other obstacles to compliance. Assessing the feasibility of frequent visits for blood tests and physical examination and less frequent visits for imaging studies is essential prior to deciding upon surveillance as a management strategy. Primary chemotherapy lowers the risk of relapse from about 30% to about 2%, and thus the benefit of surveillance and the risk associated with noncompliance with surveillance are much smaller in a patient who has been treated with primary chemotherapy. RPLND also lowers the risk of relapse but by a lesser degree than primary chemotherapy.

A second reason that surveillance may not be the best option for some men with clinical stage I (CSI) NSGCT has to do with patient preference. Being diagnosed with cancer is often psychologically traumatic and disruptive, resulting in time away from work or school, lost income, as well as anxiety and distress. Relapse of the cancer repeats this trauma and disruption, often with greater severity. Moreover, relapse comes at an unpredictable time and cannot be planned or incorporated into the patient’s schedule with regard to education, career, or family. For some patients, the ability to choose to have chemotherapy now (rather than to possibly receive it at an unpredictable future time) and to have greater peace of mind as a result of a near-zero risk of relapse outweighs the downsides of receiving chemotherapy that they probably don’t need. Shared decision making is thus appropriate with regard to management of stage I NSGCT so that the patient’s values and priorities can be incorporated into the decision-making process.

In choosing a management strategy, assessing risk of relapse is important. The most commonly used risk factor for relapse is the presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) in the primary tumor. The other often-used risk factor is a predominance of embryonal carcinoma (EC). Roughly half of men with LVI will relapse, and in some studies a predominance of EC further increases that risk. While it is well documented that men with a high risk of relapse can be safely managed with surveillance, surveillance is often less attractive to these men and their physicians. Some experts prefer a risk-adapted approach, while others prefer surveillance for all patients able to comply with a surveillance schedule. A risk-adapted approach typically means treating men with LVI while surveilling men without LVI. Studies of this approach have generally given two cycles of BEP chemotherapy to men with an increased risk of relapse, although a single cycle of BEP produces a relapse rate of less than 5%.

In summary, surveillance is a good option for all men with CSI NSGCT who are willing to comply with the surveillance schedule, but some men may prefer treatment with chemotherapy. Men without LVI can be treated with a single cycle of BEP, but men with LVI who decline surveillance should be treated with two cycles of BEP. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is also an option but should only be performed if a surgeon who performs the operation frequently is available. RPLNDs performed by surgeons who perform the operation infrequently yield inferior results.

3. Is surveillance the best option for all men with stage I testicular seminomas?

No. Surveillance is the best option for most but not all men with stage I testicular seminoma. Following orchiectomy, the risk of relapse for CSI seminoma of the testis is about 15% to 18%: surveillance spares more than four out of five men unnecessary additional therapy. Moreover, surveillance results in long-term disease specific survival of over 99%. So treating with carboplatin chemotherapy or radiation therapy after orchiectomy does not increase either disease-specific or overall survival. The rationale for treating CSI seminoma is not based on preventing deaths from testis cancer but rather on wanting to lower the risk of relapse because relapse and the subsequent need for treatment can be highly disruptive.

Treatment options for clinical stage I seminoma include surveillance, one or two cycles of single-agent carboplatin chemotherapy, and radiation therapy to either a para-aortic strip field or a dogleg (aka hockey-stick) field that includes the para-aortic strip plus the proximal ipselateral hemipelvis. Relapse rates are 15–18% with surveillance, 5% with a single cycle of carboplatin, 4% with radiation therapy, and 2% with two cycles of carboplatin. Radiation therapy has been less popular over the past decade because of extensive data showing an increased risk of being diagnosed with a variety of cancers after radiation therapy for seminoma. Whether carboplatin at the doses used in this setting is associated with significant late toxicity is not yet clear, but both cisplatin and carboplatin have been associated with a higher risk of second cancers when used at higher doses. The bottom line is that surveillance is the preferred option for most men, but two doses of carboplatin produce the lowest relapse rate for men who prefer active treatment.

4. What are the preferred surveillance schedules for testicular seminomas and nonseminomas?

For patients with clinical stage I testis cancer, surveillance schedules must balance the benefit of detecting a relapse as early as possible against the potential harm of radiation exposure and the need not to waste medical resources on unnecessarily intensive testing. Clinical stage I testicular seminoma typically relapses in the retroperitoneum with normal STM levels. As a result, cross-sectional imaging is the only reliable way to detect relapse. Fortunately, seminomas tend to grow more slowly than nonseminomas. There are a variety of different scanning schedules that have been published. The Princess Margaret Hospital schedule has been used in one of the largest experiences with surveillance, and they have obtained a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and physical examination at the following intervals: every 4 months for the first 3 years, every 6 months for the next 3 years, and then once a year until the patient is 10 years out. Chest X-ray is obtained at alternating visits for the first 6 years and then annually until year 10. While magnetic resonance imaging may one day replace CT scans and thus eliminate ionizing radiation, it is not clear that they are as reliable for detecting relapse due to the increased difficulty of interpreting them accurately.

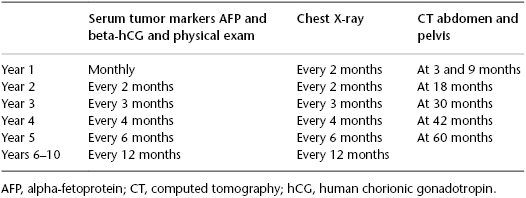

For stage I nonseminomas, a more intensive surveillance schedule is used, but a number of guidelines recommend obtaining CT scans at frequent intervals that are not supported by solid evidence. An international study compared a surveillance schedule that obtained CT scans at months 3 and 12 to a schedule that included scans at months 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months. No difference in outcome was reported. Nonetheless, many experts are uncomfortable with stopping CT scans at 12 months due to the fact that a significant number of relapses occur in the second and third years. The surveillance schedule shown in Table 99.1 is thus recommended.

Table 99.1 Surveillance schedule of clinical stage I (CSI) nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs).