CHAPTER 6. Food for life

June Gordon

Diet and diabetes – from past to present 123

The importance of diet 124

The role of the healthcare professional in providing dietary advice 124

The aims and goals of dietary advice 125

Current dietary recommendations 126

The dietary management of diabetes 131

Carbohydrate management 136

Additional dietary considerations 140

Specific considerations 143

Conclusion 148

References 148

Website addresses 150

Diabetes is one of the oldest diseases known to man and historically diet has been linked with both its cause and cure. For centuries little was known about the disease and the search for a dietary cure relied on trial and error. When it was discovered that the urine of people with diabetes was sweet, it was thought that the diet should be rich in carbohydrate to make up for these urinary losses. An alternative view was that the body could not cope with carbohydrate foods and that they should therefore be avoided.

Dietary advice fluctuated between the two extremes of high-carbohydrate ‘cures’ (based on skimmed milk and oatmeal) to low-carbohydrate diets of meat and boiled vegetables. Even after the discovery of insulin in 1921, carbohydrate restriction was advocated.

Today, diet still plays a central role in the management of diabetes, but the composition has changed considerably and recommendations are now in line with those for a healthy diet for the general population. There are, however, some important differences in emphasis for those with diabetes, which warrant intervention and monitoring to ensure that the nutritional objectives are met.

Diet is an essential component of diabetes management and it is said to be the cornerstone of treatment. For many it is the only form of treatment required. Approximately 80% of people diagnosed will have type 2 diabetes and will be controlled on either diet alone or diet and oral hypoglycaemic agents or diet and insulin therapy. The remaining 20% will have type 1 diabetes and will be controlled on diet and insulin injections. Hence, food choice and eating habits are important aspects of management of diabetes.

THE ROLE OF THE HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL IN PROVIDING DIETARY ADVICE

The clinical standards for diabetes (Clinical Standards Board for Scotland (CSBS) 2001) state that it is desirable that people with diabetes have appropriate access to key personnel, including dieticians. Both the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS; see Chapter 4) and the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT; see Chapter 5) demonstrate the value of dietetic intervention from diagnosis onwards. However, this advice should be part of a comprehensive management plan (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) 2001). The first 3 months from diagnosis have been shown to be vitally important in determining the response to dietary intervention (UKPDS 1990). Given the projected increase in type 2 diabetes, the ideal that dietary information be given only by a diabetes specialist dietician is unlikely to be met (Dyson 2003) and there might be a delay before newly diagnosed individuals have access to a dietician. In these cases, the healthcare professional will be required to give first-line advice. Suitable advice to give to a person newly diagnosed with diabetes is given in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1

Initial dietary advice suitable for a person newly diagnosed with diabetes before his or her appointment with a dietician

▪ Quench thirst with water or sugar-free drinks, e.g. diet lemonades or low-calorie diluting drinks

▪ Have regular meals, avoiding fried or very sugary foods

▪ Eat plenty of vegetables with cereal, bread, pasta, potato, rice or chapatti as the main part of the meal

▪ Have meat, fish, chicken, eggs or pulses as a small part of each meal

Diabetes UK produces general diet information leaflets, which can be useful as first-line advice.

The frequency of visits to a dietician will depend on available resources and local policies and protocols. Some hospital and community dietetic departments produce training packs and run training courses for other healthcare professionals involved in diabetes care. Whatever the situation, it is worth making contact with the local dieticians, as good communication can only benefit the individual as well as ensure consistency of advice. Other healthcare professionals can play a vital role in providing general dietary guidance. They can also reinforce dietetic advice and identify specific situations where more detailed information is required and refer on as appropriate.

THE AIMS AND GOALS OF DIETARY ADVICE

The immediate treatment aim is to control hyperglycaemia; the ultimate aim is to allow the person to lead as normal a life as possible, in good health, and for most people to achieve a weight as close as possible to the ‘ideal’. The overall aims and goals of nutritional advice are summarised in Box 6.2.

Box 6.2

Aims and goals of dietary advice (Diabetes UK 2003)

The aim is to provide those who need advice with the information required to make appropriate choices on the type and quantity of food eaten. The advice must:

▪ Take account of the individual’s personal and cultural preferences, beliefs and lifestyle

▪ Respect the individual’s wishes and willingness to change

▪ Be adapted to the specific needs of the individual, which might change with time and circumstance, e.g. age, pregnancy, nephropathy, intercurrent illness and other illnesses

The beneficial effects of physical activity in the prevention and management of diabetes and the relationship between exercise, energy balance and body weight are an integral part of nutrition counselling. The goals of dietary advice are to:

▪ To maintain or improve health through the use of appropriate and healthy food choices

▪ To achieve and maintain optimal metabolic and physiological outcomes, including:

▪ reduction of risk for microvascular disease by achieving near normal glycaemia without undue risk of hypoglycaemia

▪ reduction of risk for macrovascular disease, including management of body weight, dyslipidaemia and hypertension

▪ To optimise outcomes in diabetic nephropathy and any concomitant disorder such as coeliac disease or cystic fibrosis

BACKGROUND

Before the 1980s, dietary advice centred on carbohydrate restriction as the only means of controlling blood glucose levels. People were advised to limit their intake of carbohydrate foods such as bread, potatoes, rice, pasta and cereals and to fill up on foods such as meat, cheese, eggs, cream and butter. This resulted in a diet low in carbohydrate but high in fat. Research in the 1970s (Brunzell et al 1974, Simpson et al 1979) showed that high-carbohydrate diets could actually improve diabetic control, providing the carbohydrate was in a complex, high-fibre form. Studies were also beginning to show that reducing fat intake in non-diabetic people resulted in reduced morbidity from cardiovascular disease (Miettinen et al 1977). This led researchers to ask whether the high-fat diet could be contributing to the increased risk of heart disease in people with diabetes.

As a result of this research, guidelines were published in both the USA (American Diabetes Association 1979) and the UK (British Diabetic Association Nutrition Subgroup 1982). These overturned decades of teaching by recommending that people with diabetes should consume a diet high in carbohydrate and low in fat. These were considered to be radical documents, but they were followed by the introduction of almost identical policies by diabetes associations in many other countries. These were also very similar to nutritional guidelines published for the general population in the UK (Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) 1984) and by the World Health Organization (James et al, WHO 1988) for Europe. This had positive implications in that people with diabetes were no longer being advised to follow a ‘special diabetic diet’.

These guidelines have now become established practice throughout Europe and North America, although there have been some shifts in emphasis in the light of new knowledge and clinical experience (American Diabetes Association 2003, Diabetes UK Nutrition Subcommittee 2003, European Association for the Study of Diabetes 2000).

CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS

The current recommendations on the composition of the diet for diabetes are summarised in Table 6.1 and Table 6.2.

| Component | Comment |

|---|---|

| Protein | |

| Not >1 g per kg body weight | |

| Fat | |

| Total fat | <35% of energy intake |

| Saturated + transunsaturated fat | <10% of energy intake |

| N-6 polyunsaturated fat | <10% of energy intake |

| N-3 polyunsaturated fat | Eat fish, especially oily fish, once or twice weekly |

| Fish oil supplements are not recommended | |

| Cis-monounsaturated fat | 10–20% = 60–70% of energy intake |

| Carbohydrate | |

| Total carbohydrate | 45–60% |

| Sucrose | Up to 10% of daily energy provided it is eaten in the context of a healthy diet. Those who are overweight or who have raised blood triglyceride levels should consider using non-nutritive sweeteners where appropriate |

| Fibre | |

| No quantitative recommendation | |

| Soluble fibre | Found in foods such as pulses, oats and fruit |

| Has beneficial effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism | |

| Insoluble fibre | Found in wholegrain versions of bread, flour and pasta, brown rice and high fibre breakfast cereals |

| Has no direct effects on glycaemic and lipid metabolism but its high satiety content may benefit those trying to lose weight and it is advantageous to gastrointestinal health | |

| Vitamins and antioxidants | |

| Encourage foods naturally rich in vitamins and antioxidants | |

| There is no evidence for the use of supplements and evidence that some are harmful | |

| Salt | |

| <6 g sodium chloride per day | |

| Choice | Comment |

|---|---|

| Nutritive sweeteners: | |

| ▪ Fructose | No proven advantage over sucrose |

| ▪ Sugar alcohols (e.g. sorbitol) | Lower cariogenic effect but no other advantages over sucrose May cause diarrhoea |

| Non-nutritive (artificial/intense) | Useful in beverages sweeteners Potentially useful in the overweight Safe if acceptable daily intake is not exceeded Heavy users should use a variety of different products |

| [Diabetic] foods | Unnecessary, expensive Can cause diarrhoea Not recommended |

| Plant stanols and sterols | Approximately 2 g per day can reduce LDL-cholesterol by 10–15% (see section on dyslipidaemia on p. 146) |

| Fat replacers and substitutes | Can facilitate weight loss Long-term studies needed |

| Herbal preparations | No convincing evidence of benefit |

The main differences in emphasis from previous recommendations (British Diabetic Association Nutrition Subgroup 1992) are:

▪ More flexibility in the proportions of energy from carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat. Monounsaturated fats are promoted as the main source of dietary fat because of their lower atherogenic potential (Kratz et al 2002). Sources of the different types of fatty acids are shown in Table 6.3.

| Type of oil | Example |

|---|---|

| Cis-monounsaturated | Olive oil Some rapeseed oils Fat spreads derived from olive oil |

| Trans-unsaturated | Hydrogenated vegetable oils Hard margarine Manufactured foods containing hydrogenated vegetable oils (e.g. pies, pastry, biscuits, cakes) Fat spreads derived from these oils |

| Polyunsaturated | N-6 Corn, sunflower Safflower oil, soya bean oil and seeds N-3 Oily fish and marine oils |

▪ More active promotion of carbohydrate foods with a low glycaemic index (GI) (see p. 140).

▪ Greater emphasis on the benefits of regular exercise.

TRANSLATING RECOMMENDATIONS INTO PRACTICAL ADVICE

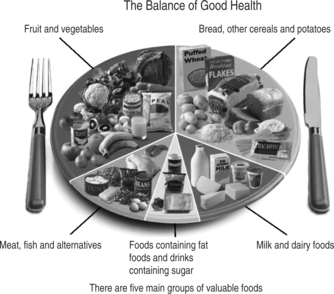

The scientific evidence for the effect of diet on diabetes management needs to be translated into practical and realistic advice for the individual. Because the nutritional objectives for those with diabetes are very similar to those advocated for the entire population, dietary guidance should be based on a framework of healthy eating principles such as the Balance of good health (Health Education Authority (HEA) 1994) shown in Fig. 6.1. More information on this is given in Box 6.3.

|

| Fig. 6.1The balance of good health (HEA 1994).Reproduced with kind permission of the Food Standards Agency |

Box 6.3

The Balance of good health plate model

▪ Primarily a device for encouraging healthy eating practices

▪ A visual method, with the dinner plate serving as a pie chart. This shows the proportions of the plate that should be covered by the various food groups

▪ Simple and adaptable; embodies the principles of healthy eating and promotes memory and understanding through visual methods

▪ Easily implemented in residential and nursing homes

This does not mean, however, that dietary advice is simply a matter of healthy eating guidance; many other issues have to be borne in mind and specific aspects relevant to diabetes will need to be superimposed on this. Table 6.4 shows how it can be adapted for diabetes.

| Food group | Points to emphasise |

|---|---|

Bread, cereal foods and potatoes These should form the largest component of meals and snacks | Quantity and timing: these need to remain fairly constant from day to day Good food choices: pasta, rice, bread, chapattis, potatoes, breakfast cereals (especially oat-based) Reduce the amount of fat added to these foods Wholemeal/wholegrain bread and cereals are high in fibre and have advantages in terms of satiety and helping to prevent constipation |

Fruit and vegetables At least 5 servings of a variety of these foods should be eaten every day | These have major health benefits for people with diabetes 1–2 servings of vegetables should be eaten with main meals More use should be made of fresh fruit as a snack or dessert Frozen or canned fruits and vegetables are useful alternatives to fresh varieties Fruit juice should be regarded as a sugar-containing drink and so not consumed on its own – only with meals Encourage consumption of salad or vegetables with manufactured convenience foods or ready meals |

| Milk and dairy products 2–3 servings daily | Low/reduced-fat varieties of milk, yoghurt, fromage frais, etc., should be chosen Full-fat cheese should be used with care, especially by the overweight; it is best used as part of a meal rather than a snack Cream should only be used as an occasional treat |

| Meat, fish, pulses and alternatives 2 servings/day | Greater use should be made of pulses (peas, beans and lentils), either as an alternative to meat or as a way of making a smaller quantity of meat go further. Fresh, canned or dried pulses are all suitable Ideally at least 2 portions of fish should be consumed every week, one of which should be oily fish Fat avoidance is important, e.g. meat should be lean: visible meat fat should be trimmed off after cooking. Consumption of meat products (e.g. burgers, pies, sausage rolls) or high-fat meat mixtures (mince) should be kept to a minimum. Poultry is only a low source of fat if the skin is removed and the fat that appears during cooking is discarded |

Fat-rich and sugar-rich foods These should be kept to a minimum | Sugar-rich foods: The diet does not have to be sugar free, but sugar-rich confectionary and drinks will impair glycaemic control if consumed at inappropriate times or in addition to meals Low-calorie [diet] counterparts Either ordinary jam/marmalade or reduced-sugar varieties can be used in small amounts on bread Small amounts of sugar-containing biscuits or cakes can be eaten as scheduled snacks, but higher fibre, lower sugar choices are best, e.g. teabreads, fruit cake, English muffins, plain cakes and biscuits. Those who are overweight should be encouraged to make more use of fruit as snacks Intense artificial sweeteners should be used if sweet-tasting drinks are required Fat-rich foods: Sources of fat should be avoided as much as possible Food should be boiled, baked, grilled, dry roasted or microwaved, but not fried Minimum amounts of fat should be spread on bread, added to food or used in cooking. Reduced-fat monounsaturated spread and small amounts of monounsaturated oils (olive or rapeseed or canola) are the best choices High-fat snack foods such as crisps and biscuits should be eaten less often and replaced by healthier alternatives such as fruit, low-fat yoghurt or wholewheat crispbread |

It takes considerable skill to apply the nutritional objectives of diabetes management in a realistic and practical way. Initially, people should be assessed to determine their willingness to change their dietary behaviour (SIGN 2001). A simple, flexible approach is required and counselling skills should be used to motivate the individual to make positive and achievable dietary changes (see Chapter 3). Not everyone will be able (or willing) to achieve all dietary goals and a balance should be found between what is acceptable, achievable and beneficial to that individual person. For most, the actual target will be to make specific dietary changes in the right direction, i.e. towards the ideal. The nature of these changes will vary according to individual nutritional and clinical priorities, habitual diet and lifestyle and the prevalence of risk factors. The focus should always be on modifying an individual’s existing eating habits (food choice and the timing of its consumption) in a realistic and achievable way. Pre-printed standardised diet sheets alone are of little benefit in modern day diabetes management. The dietary management of diabetes should take place in the stages outlined in Box 6.4.

Box 6.4

Stages in the dietary management of diabetes

▪ Assessment: to decide which aspects of the diet need to be changed and what changes are possible, information will have to be gathered on the person’s background and usual eating habits. Nutritional, personal and clinical information will be relevant in determining the advice given

▪ Education: dietary education is essential to help individuals make the diet and lifestyle changes necessary to optimise diabetic control and long-term health. This cannot be delivered as a single package in a single session. Every one is different in terms of his or her nutritional priorities, dietary targets, pace and degree of change. Education should, therefore, be tailored to the needs of the individual

▪ Monitoring progress: follow-up and review are essential, but the frequency of this will depend on the type of treatment, the person’s ability and confidence, diabetic control and whether or not additional problems such as renal or coeliac disease exist

Approximately 80% of people with type 2 diabetes, and many with type 1 diabetes, are overweight and hence weight loss and stabilisation will be a major priority in their management.

Moderate weight loss of 5–10 kg can help to improve blood glucose and lipid levels, reduce insulin resistance and improve hypertension. It has also been shown that losing weight can improve life expectancy in overweight people with type 2 diabetes by an average of 3–4 months for each 1 kg (2.2 lb) of weight lost (Lean et al 1990). The largest published study to date into weight loss in overweight people with diabetes (Williamson et al 2000) showed that a weight loss of 11% of initial body weight was associated with a reduction in mortality of 25% and in heart disease of 28%. However, losing even small amounts of weight has health benefits. It is therefore worth stressing the benefits of any weight loss and maintenance of this loss for the overweight person with type 2 diabetes.

Assessing body weight and shape

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree