Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome

Lyon Sud Hospital, Claude Bernard Lyon University, Pierre-Bénite, France

1. Early-stage mycosis fungoides (MF): what are the pitfalls?

The diagnosis of early MF (patch and early-plaque mycosis fungoides) is a major diagnostic challenge in dermatology and hematology. Both the dermatologic differential diagnoses and MF atypical presentations are numerous. The lack of a specific marker differentiating early MF from benign inflammatory dermatitis presents significant difficulties in the assessment and management of suspected MF patients. It cannot be overemphasized that the diagnosis of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) requires clinicopathologic correlation, and review by a pathologist experienced in these disorders is strongly recommended. It is also important to recognize that it is not uncommon for the diagnosis of MF to remain elusive for many years, often requiring observation and repeated biopsies. Such an approach avoids embarking on numerous investigations in a disease that is generally indolent and in which the outcome is not altered by aggressive early intervention. An algorithm has been proposed in 2005 by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma to standardize the criteria for early MF (Table 50.1).

Table 50.1 International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma criteria for early MF (Source: Data from Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Dec;53(6):1053–63).

| Criteria | Scoring system |

|---|---|

| Clinical Basic Persistent and/or progressive patches or thin plaques Additional

Basic Superficial lymphoid Infiltrate Additional

| 2 points for basic criteria and two additional criteria 1 point for basic criteria and one additional criterion 2 points for basic criteria and two additional criteria 1 point for basic criteria and one additional criterion 1 point for clonality 1 point for one or more criteria |

The clinical presentation of classic patch-phase MF is characterized by variability in the size, shape, and color of individual lesions. Most MF patch lesions are large (>5 cm in diameter) (Figure 50.1). Digitate lesions are uncommon in MF and would make one suspect the presence of digitiform parapsoriasis, which is a variant of small plaque parapsoriasis. Untreated lesions of MF often expand slowly to form well-demarcated lesions that vary in size with or without coalescence and may also undergo spontaneous clearing in areas. Another important clinical feature that is relatively specific for early MF is the presence of poikiloderma. Poikiloderma is defined clinically as the local juxtaposition of mottled pigmentation, telangiectasia, and epidermal atrophy (cigarette paper wrinkling) interspersed with slight infiltration (Figure 50.2).

Taking into account the possible serious effects and the limited availability of efficacy data, topical and skin-directed treatments are recommended first. As the use of early application of therapy does not affect survival, a nonaggressive approach to therapy is warranted with treatment aimed at improving symptoms while limiting toxicity. As patients with stage IA disease have a long life expectancy, an expectant policy may be a legitimate management option in selected patients, provided that it incorporates careful monitoring. Given that multiple skin sites are often involved, the initial treatment is primarily a skin-directed therapy (SDT), which aims to control skin lesions while minimizing morbidity. The key choices for SDT are topical or intralesional corticosteroids or psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) or ultraviolet B (UVB). Indeed, for patients with limited patch disease, topical steroids often control the disease for many years, and often this is the only form of therapy required for such patients. Patch and thin-plaque MF can be treated with topical corticosteroids.

2. What is the relevance of transformation in mycosis fungoides?

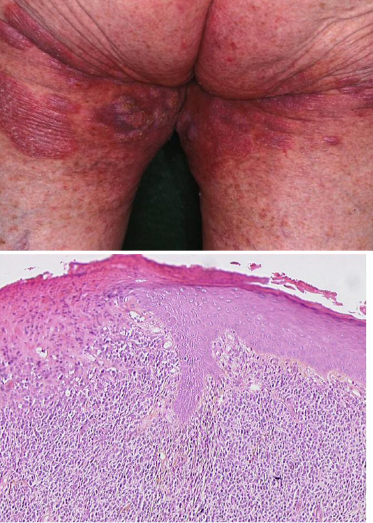

Large-cell transformation is known to occur in patients with either Sézary syndrome or MF. Transformed mycosis fungoides (T-MF) is a well-defined histopathological condition with the presence of large cells (four times or more the size of a small lymphocyte) exceeding 25% of the cell population of the infiltrate or forming microscopic nodules (Figure 50.3). The incidence of such a transformation is diversely appreciated, but although such a transformation has been reported to occur in 8% to 55% of cases, few studies on the prognostic value of specific criteria leading to early diagnosis of MF transformation are available in the literature.

Recent studies in a group of 26 cases and in a series of 45 patients with T-MF showed conflicting data about clinical features associated with a poor outcome. In the first one, poor survival is associated with early transformation (less than 2 years after initial diagnosis of MF) and advanced clinical stage at the time of T-MF (IIB–IV versus I–IIA). In the second older age (60 and older) and extracutaneous invasion (stage IV) were found correlated with a poor prognosis.

In our series, the median delay from the initial diagnosis of MF to documentation of the onset of a large-cell transformation was 3.6 years (range: 1–115 months) (12 months in Diamandinou et al. 1998) (Table 50.1). We also observed that fatal cases had a relatively shorter delay from initial diagnosis of MF to transformation. Survival time from transformation ranged from 12 months to 67 months (median: 27 months, according to data for Greer et al. 1988). As already published, our data demonstrate that advanced stage of the disease at the time of transformation (IIB and IV) adversely influences the prognosis: our four patients with fatal outcome were at least at stage IIB, and two patients in whom we had to administer systemic chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation were at stage IVA. No or weak correlation between prognosis and age or β2 microglobulin or blood lactate dehydrogenase levels in univariate analysis has been evidenced in previous studies. In our series, age (younger or older than 60) was not significantly associated with prognosis.

Although histopathological criteria for the T-MF diagnosis are well defined with a skin biopsy showing large cells (≥4 times the size of a small lymphocyte) exceeding 25% of the infiltrate or forming microscopic nodules, a differential diagnosis of T-MF remains difficult. Vergier et al. (2000) have emphasized the necessity to differentiate large T-lymphocytes from histiocytes and macrophages because the prognosis of “granulomatous MF” is better than that of T-MF. Immunohistochemistry with anti-CD3 and CD68 antibodies could be used for that purpose. In our population of T-MF, CD68 immunostaining has been performed in order to better exclude histiocytic cells from the count of tumoral large cells.

Vergier et al. (2000) also stressed the point that the differential diagnosis between T-MF with CD30-positive cells and MF associated with CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphomatoid papulosis or CD30+ large-cell cutaneous lymphoma), the later bearing a much better prognosis, can be very difficult. T-MF diagnosis can be regarded as highly probable when clinical transformation occurs within clinically typical MF lesions and in the coexistence of cerebriform lymphocytes mixed with fewer than 75% of CD30+ large T-cells.

As already described by Vergier et al. (2000), we reported that the patient’s evolution is the most reliable criterion with which to distinguish CD30+ T-MF from MF associated with primary CD30+ large-cell lymphoma. This is in accordance with the usually favorable evolution of the CD30+ cutaneous lymphoproliferative disorders (CLPDs) and their marked tendency to spontaneously undergo regression. Apoptosis of tumor cells is considered a key mechanism in tumor regression. Proapoptotic proteins are expressed at high levels in CD30+ CLPD and may play a crucial role in mediating apoptosis-linked regression of tumors.

Recently Benner et al. confirmed that CD30 expression was a strong and independent predictor of improved survival, both in the total group of patients and in patients with transformation limited to the skin. Because patients may have a combination of favorable and unfavorable prognostic factors, they developed a prognostic index that may better predict prognosis and be a useful tool in selecting the appropriate treatment. For that purpose, the most discriminating independent prognostic factors for disease-specific survival were selected. For the total group of patients with transformed MF, these were the presence of generalized skin lesions, extracutaneous transformation, CD30 negativity, and folliculotropic MF. Patients with 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 unfavorable prognostic factors had a 2-year disease-specific survival rate of 83%, 85%, 52%, 14%, and 33%, respectively. For the group of patients with only transformed skin lesions, CD30 negativity, folliculotropic MF, and the presence of generalized skin lesions were selected. Patients with 0, 1, 2, or 3 unfavorable prognostic factors had a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 73%, 61%, 19%, and 0%, respectively. The accuracy of the prognosis index now has to be validated prospectively and may have an impact on therapeutic decisions.

In conclusion, transformation of MF occurs in about 8% of CTCLs, most often in the first years of the disease (median: 3.5 years); it is strictly correlated with a poor prognosis (median survival: 27 months). Markers of poor prognosis are the advanced initial stage of MF at transformation and the negativity of the CD30 immunostaining of the large transformed cells (the association of CD30− of the large cells with CD20+ B-cell peritumoral infiltrate).

3. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: the same or distinct entities?