HIV-Associated Lymphoma

National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA

1. What are the most important etiological factors for the development of HIV-associated lymphoma?

The pathogenesis of HIV-associated lymphoma is complex and involves the interplay of several biological factors, such as chronic antigen stimulation, co-infecting oncogenic viruses such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and human herpes virus-8 (HHV8), genetic abnormalities, and cytokine deregulation. Most HIV-associated lymphomas are of B-cell lineage and demonstrate clonal rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes. T-cell lymphomas are uncommonly observed in the setting of HIV infection.

Chronic antigen stimulation, which is associated with HIV infection, can lead to polyclonal B-cell expansion, and this may then promote and result in the emergence of monoclonal B-cells. Recently, circulating free light chains were found to be elevated in patients at increased risk of HIV-associated lymphomas. These may represent markers of polyclonal B-cell activation and, in the future, may be useful for identifying HIV-positive individuals at increased risk for the development of lymphoma.

EBV is the most commonly found oncogenic virus in HIV-associated lymphomas and is observed in approximately 40% of cases. All cases of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) and most cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) harbor EBV, as do the majority of DLBCL cases with immunoblastic features. Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cases also harbor EBV in addition to HHV8. In contrast, EBV is only variably present in Burkitt lymphoma (BL) (30–50%) and plasmablastic lymphoma (50%), and it is typically absent in centroblastic lymphomas. EBV-positive HIV-associated lymphomas frequently express the EBV-encoding transforming antigen latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1), which activates cellular proliferation through the activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway and may induce B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL2) overexpression, promoting B-cell survival and lymphomagenesis.

2. How has the prognosis for patients with HIV-associated lymphoma changed over recent years with the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy?

It has improved significantly. Following the arrival of combination antiretroviral therapy (CART) and the development of novel therapeutic strategies, most patients with HIV-associated lymphomas are now cured of their disease, in contrast to the pre-CART era. The majority of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and BL in particular have an excellent outcome, with recent studies supporting the role of rituximab in these diseases (this is further discussed in a later question in this chapter). The curability of many patients with HIV-associated lymphoma is now similar to that of their HIV-negative counterparts. New treatment frontiers need to focus on improving the outcome for patients with advanced immune suppression in particular and for those with adverse tumor biology such as the activated B-cell (ABC) type of DLBCL and the virally driven lymphomas.

3. What are the most important prognostic factors in HIV-associated lymphoma?

While the International Prognostic Index (IPI) is the standard prognostic assessment tool in HIV-negative DLBCL, its applicability to HIV-associated DLBCL lymphomas is questionable. Indeed, in a recent study of short-course EPOCH-R (infusional etoposide, vincristine, and doxorubicin with prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab) in newly diagnosed HIV-associated DLBCL, the IPI did not predict progression-free survival (PFS) or OS. The prognostic importance of CD4 cell count and immune function in HIV-associated DLBCL, neither of which are part of the IPI, are the most likely confounding variables. Patients with CD4 counts lower than 100 cells/μl are at increased risk of serious opportunistic infections and death.

Furthermore, patients with severe immune suppression have a higher incidence of immunoblastic subtypes, most of which are of postgerminal center or ABC derivation, and these patients have a poor outcome compared to patients with preserved immunity and higher CD4 counts, where the “germinal center B-cell-like” subtype is more common. There has been controversy about the prognostic role of the cell of origin in HIV-associated DLBCL. A recently report from the AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC) did not find an association between cell of origin and outcome, but this analysis was retrospective and included patients treated with a variety of different regimens, which may have confounded results. Involvement of the CNS, which is increased in HIV-associated aggressive B-cell lymphomas, also confers an adverse prognosis.

4. How should patients with HIV-associated lymphoma be evaluated, and what different and additional tests do they require compared to HIV-negative patients?

Patients should have a comprehensive medical history with attention paid to signs and symptoms of lymphoma, and a detailed HIV history including prior opportunistic infections, immune function, HIV viral control, and a history of all antiretroviral treatment with special attention paid to any history of antiretroviral drug resistance. Then, the physical examination should include in particular a careful assessment of all lymph node regions as well as the liver and spleen. Laboratory studies, including a complete blood count, a chemistry profile with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and uric acid levels, a CD4 cell count, and HIV viral load, should be performed. HIV and hepatitis B and C serologies should be assessed. Ideally, an excisional biopsy should be performed and an entire lymph node evaluated by an expert hematopathologist who is experienced in the diagnosis of lymphomas and aware of all of the pitfalls and nuances involved; sometimes, a core needle biopsy may be acceptable, but a fine-needle aspiration biopsy is usually inadequate for a definitive diagnosis. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be done because involvement by lymphoma is found in up to 20% of cases. Patients with aggressive B-cell lymphomas should have a lumbar puncture for analysis of cerebrospinal fluid by both cytology and flow cytometry to check for the presence of leptomeningeal lymphoma.

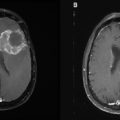

Imaging studies should include computed tomography (CT) scanning of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Radiographic evaluation of the head should also be performed, preferably by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is useful in HIV-negative aggressive lymphomas, but its role in HIV-associated lymphomas is poorly studied and can be confounded by inflammation from HIV-associated nodal reactive hyperplasia, infections, and lipodystrophy. Prior experience evaluating FDG-PET in HIV-associated lymphoma is limited to small retrospective series. In one of these studies of 13 patients with HIV, although a negative scan during and following the completion of treatment was associated with a lasting complete remission (CR), most scans were positive but not predictive of remission. Similarly, in another small study of FDG-PET in HIV-associated NHL, PET positivity during and after treatment was often associated with benign findings.

5. What is the role of rituximab in HIV-associated DLBCL, and should it be standard in upfront therapy?